Americans Respond: Perspectives on the Global War, 1914 –1917

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Jewish Yearbook

JEWISH STATISTICS 277 JEWISH STATISTICS The statistics of Jews in the world rest largely upon estimates. In Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and a few other countries, official figures are obtainable. In the main, however, the num- bers given are based upon estimates repeated and added to by one statistical authority after another. For the statistics given below various authorities have been consulted, among them the " Statesman's Year Book" for 1910, the English " Jewish Year Book " for 5670-71, " The Jewish Ency- clopedia," Jildische Statistik, and the Alliance Israelite Uni- verselle reports. THE UNITED STATES ESTIMATES As the census of the United States has, in accordance with the spirit of American institutions, taken no heed of the religious convictions of American citizens, whether native-born or natural- ized, all statements concerning the number of Jews living in this country are based upon estimates. The Jewish population was estimated— In 1818 by Mordecai M. Noah at 3,000 In 1824 by Solomon Etting at 6,000 In 1826 by Isaac C. Harby at 6,000 In 1840 by the American Almanac at 15,000 In 1848 by M. A. Berk at 50,000 In 1880 by Wm. B. Hackenburg at 230,257 In 1888 by Isaac Markens at 400,000 In 1897 by David Sulzberger at 937,800 In 1905 by "The Jewish Encyclopedia" at 1,508,435 In 1907 by " The American Jewish Year Book " at 1,777,185 In 1910 by " The American Je\rish Year Book" at 2,044,762 DISTRIBUTION The following table by States presents two sets of estimates. -

Leigh Chronicle," for This Week Only Four Pages, Fri 21 August 1914 Owing to Threatened Paper Famine

Diary of Local Events 1914 Date Event England declared war on Germany at 11 p.m. Railways taken over by the Government; Territorials Tue 04 August 1914 mobilised. Jubilee of the Rev. Father Unsworth, of Leigh: Presentation of illuminated address, canteen of Tue 04 August 1914 cutlery, purse containing £160, clock and vases. Leigh and Atherton Territorials mobilised at their respective drill halls: Leigh streets crowded with Wed 05 August 1914 people discussing the war. Accidental death of Mr. James Morris, formerly of Lowton, and formerly chief pay clerk at Plank-lane Wed 05 August 1914 Collieries. Leigh and Atherton Territorials leave for Wigan: Mayor of Leigh addressed the 124 Leigh Territorials Fri 07 August 1914 in front of the Town Hall. Sudden death of Mr. Hugh Jones (50), furniture Fri 07 August 1914 dealer, of Leigh. Mrs. J. Hartley invited Leigh Women's Unionist Association to a garden party at Brook House, Sat 08 August 1914 Glazebury. Sat 08 August 1914 Wingate's Band gave recital at Atherton. Special honour conferred by Leigh Buffaloes upon Sun 09 August 1914 Bro. R. Frost prior to his going to the war. Several Leigh mills stopped for all week owing to Mon 10 August 1914 the war; others on short time. Mon 10 August 1914 Nearly 300 attended ambulance class at Leigh. Leigh Town Council form Committee to deal with Tue 11 August 1914 distress. Death of Mr. T. Smith (77), of Schofield-street, Wed 12 August 1914 Leigh, the oldest member of Christ Church. Meeting of Leigh War Distress Committee at the Thu 13 August 1914 Town Hall. -

Campaign and Transition Collection: 1928

HERBERT HOOVER PAPERS CAMPAIGN LITERATURE SERIES, 1925-1928 16 linear feet (31 manuscript boxes and 7 card boxes) Herbert Hoover Presidential Library 151 Campaign Literature – General 152-156 Campaign Literature by Title 157-162 Press Releases Arranged Chronologically 163-164 Campaign Literature by Publisher 165-180 Press Releases Arranged by Subject 181-188 National Who’s Who Poll Box Contents 151 Campaign Literature – General California Elephant Campaign Feature Service Campaign Series 1928 (numerical index) Cartoons (2 folders, includes Satterfield) Clipsheets Editorial Digest Editorials Form Letters Highlights on Hoover Booklets Massachusetts Elephant Political Advertisements Political Features – NY State Republican Editorial Committee Posters Editorial Committee Progressive Magazine 1928 Republic Bulletin Republican Feature Service Republican National Committee Press Division pamphlets by Arch Kirchoffer Series. Previously Marked Women's Page Service Unpublished 152 Campaign Literature – Alphabetical by Title Abstract of Address by Robert L. Owen (oversize, brittle) Achievements and Public Services of Herbert Hoover Address of Acceptance by Charles Curtis Address of Acceptance by Herbert Hoover Address of John H. Bartlett (Herbert Hoover and the American Home), Oct 2, 1928 Address of Charles D., Dawes, Oct 22, 1928 Address by Simeon D. Fess, Dec 6, 1927 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Boston, Massachusetts, Oct 15, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Elizabethton, Tennessee. Oct 6, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – New York, New York, Oct 22, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Newark, New Jersey, Sep 17, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – St. Louis, Missouri, Nov 2, 1928 Address of W. M. Jardine, Oct. 4, 1928 Address of John L. McNabb, June 14, 1928 Address of U. -

World War I Timeline C

6.2.1 World War I Timeline c June 28, 1914 Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophia are killed by Serbian nationalists. July 26, 1914 Austria declares war on Serbia. Russia, an ally of Serbia, prepares to enter the war. July 29, 1914 Austria invades Serbia. August 1, 1914 Germany declares war on Russia. August 3, 1914 Germany declares war on France. August 4, 1914 German army invades neutral Belgium on its way to attack France. Great Britain declares war on Germany. As a colony of Britain, Canada is now at war. Prime Minister Robert Borden calls for a supreme national effort to support Britain, and offers assistance. Canadians rush to enlist in the military. August 6, 1914 Austria declares war on Russia. August 12, 1914 France and Britain declare war on Austria. October 1, 1914 The first Canadian troops leave to be trained in Britain. October – November 1914 First Battle of Ypres, France. Germany fails to reach the English Channel. 1914 – 1917 The two huge armies are deadlocked along a 600-mile front of Deadlock and growing trenches in Belgium and France. For four years, there is little change. death tolls Attack after attack fails to cross enemy lines, and the toll in human lives grows rapidly. Both sides seek help from other allies. By 1917, every continent and all the oceans of the world are involved in this war. February 1915 The first Canadian soldiers land in France to fight alongside British troops. April - May 1915 The Second Battle of Ypres. Germans use poison gas and break a hole through the long line of Allied trenches. -

The Republics of France and the United States: 240 Years of Friendship September 19-22, 2019 Paris, France

The Republics of France and the United States: 240 Years of Friendship September 19-22, 2019 Paris, France THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 19 7:00 p.m. Welcome Dinner Location: Hôtel de Soubise - French National Archives (Business Attire) 60 Rue des Francs Bourgeois, 75004 Paris • Doug Bradburn, George Washington’s Mount Vernon • Annick Allaigre, President, Université de Paris 8 (Vincennes Saint-Denis) • Jean-Michel Blanquer, French Minister of National Education* FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 20 Location: Automobile Club de France (Private club: coat and tie required) 6 Place de la Concorde, 75008 Paris, France 9:00 a.m. Session I: The Legacies of 1763 Scholars from France and the United States examine the larger context of the French-American relationship in the period before American Independence, with a focus on the British and French Atlantics, the slave trade, and the important geopolitical role of Native Americans. • CHAIR: Kevin Butterfield, George Washington’s Mount Vernon • Manuel Covo, University of California, Santa Barbara • Edmond Dziembowski, Université de Franche-Comté • David Preston, The Citadel 10:30 a.m. Session II: French Armies and Navies at War in America How did the military and naval forces of the United States and France overcome their social and cultural differences in order to work together to defeat Great Britain and secure American independence? 1 • CHAIR: Julia Osman, Mississippi State University • Olivier Chaline, Université Paris IV • Larrie D. Ferreiro, George Mason University • Joseph Stoltz, George Washington’s Mount Vernon 12:00 p.m. Lunch Program: François-Jean de Chastellux, the Unsung Hero Who was the Marquis de Chastellux? Based on a previously unexamined archive still privately held by the Chastellux family, new research sheds light on a heretofore unknown pivotal figure in the American Revolution who served alongside George Washington and became one of his dearest friends. -

John J. Mearsheimer: an Offensive Realist Between Geopolitics and Power

John J. Mearsheimer: an offensive realist between geopolitics and power Peter Toft Department of Political Science, University of Copenhagen, Østerfarimagsgade 5, DK 1019 Copenhagen K, Denmark. E-mail: [email protected] With a number of controversial publications behind him and not least his book, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, John J. Mearsheimer has firmly established himself as one of the leading contributors to the realist tradition in the study of international relations since Kenneth Waltz’s Theory of International Politics. Mearsheimer’s main innovation is his theory of ‘offensive realism’ that seeks to re-formulate Kenneth Waltz’s structural realist theory to explain from a struc- tural point of departure the sheer amount of international aggression, which may be hard to reconcile with Waltz’s more defensive realism. In this article, I focus on whether Mearsheimer succeeds in this endeavour. I argue that, despite certain weaknesses, Mearsheimer’s theoretical and empirical work represents an important addition to Waltz’s theory. Mearsheimer’s workis remarkablyclear and consistent and provides compelling answers to why, tragically, aggressive state strategies are a rational answer to life in the international system. Furthermore, Mearsheimer makes important additions to structural alliance theory and offers new important insights into the role of power and geography in world politics. Journal of International Relations and Development (2005) 8, 381–408. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jird.1800065 Keywords: great power politics; international security; John J. Mearsheimer; offensive realism; realism; security studies Introduction Dangerous security competition will inevitably re-emerge in post-Cold War Europe and Asia.1 International institutions cannot produce peace. -

Barthé, Darryl G. Jr.Pdf

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Becoming American in Creole New Orleans: Family, Community, Labor and Schooling, 1896-1949 Darryl G. Barthé, Jr. Doctorate of Philosophy in History University of Sussex Submitted May 2015 University of Sussex Darryl G. Barthé, Jr. (Doctorate of Philosophy in History) Becoming American in Creole New Orleans: Family, Community, Labor and Schooling, 1896-1949 Summary: The Louisiana Creole community in New Orleans went through profound changes in the first half of the 20th-century. This work examines Creole ethnic identity, focusing particularly on the transition from Creole to American. In "becoming American," Creoles adapted to a binary, racialized caste system prevalent in the Jim Crow American South (and transformed from a primarily Francophone/Creolophone community (where a tripartite although permissive caste system long existed) to a primarily Anglophone community (marked by stricter black-white binaries). These adaptations and transformations were facilitated through Creole participation in fraternal societies, the organized labor movement and public and parochial schools that provided English-only instruction. -

Political Science

A 364547 Political Science: THE STATE OF -THEDISCIPLINE Ira Katznelson and Helen V. Milner, editors Columbia University W. W. Norton & Company American Political Science Association NEW YORK | LONDON WASHINGTON, D.C. CONTENTS Ira Katznelson and Helen V. Milner Preface and Acknowledgments xiii Ira Katznelson and Helen V. Milner American Political Science: The Discipline's State and the State of the Discipline 1 The State in an Era of Globalization Margaret Levi The State of the Study of the State 3 3 Miles Kahler The State of the State in World Politics 56 Atul Kohli State, Society, and Development 84 Jeffry Frieden and Lisa L. Martin International Political Economy: Global and Domestic Interactions 118 I ]ames E. Alt Comparative Political Economy: Credibility, Accountability, and Institutions 147 ]ames D. Morrow International Conflict: Assessing the Democratic Peace and Offense-Defense Theory 172 Stephen M. Walt The Enduring Relevance of the Realist Tradition 197 Democracy, Justice, and Their Institutions Ian Shapiro The State of Democratic Theory 235 vi | CONTENTS Jeremy Waldron Justice 266 Romand Coles Pluralization and Radical Democracy: Recent Developments in Critical Theory and Postmodernism 286 Gerald Gamm and ]ohn Huber Legislatures as Political Institutions: Beyond the Contemporary Congress 313 Barbara Geddes The Great Transformation in the Study of Politics in Developing Countries 342 Kathleen Thelen The Political Economy of Business and Labor in the Developed Democracies 371 Citizenship, Identity, and Political Participation Seyla Benhabib Political Theory and Political Membership in a Changing World 404 Kay Lehman Schlozman Citizen Participation in America: What Do We Know? Why Do We Care? 433 Nancy Burns - Gender: Public Opinion and Political Action 462 Michael C. -

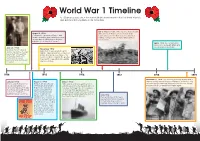

World War 1 Timeline As 100 Years Passes Since the Start of Britain’S Involvement in the First World War Let’S Take a Look at the Key Dates of This Great War

World War 1 Timeline As 100 years passes since the start of Britain’s involvement in the First World War let’s take a look at the key dates of this Great War July 1, 1916: The Battle of the Somme, troops fought August 3, 1914: at the Somme in France for over four and half Germany declares war on France, and months where over 1 million men were wounded invades neutral Belgium. Britain then sends or killed, making it one of the bloodiest battles in an ultimatum to withdraw from Belgium human history. but this is ejected by the Germans. April 6, 1918: The USA joined the allied forces along with Britain and June 28, 1914: decalred war on Germany. November 1914: Archduke Franz Ferdinand Many months were spent in ‘Trench and his wife Sophie, the night Warfare’. Opposing armies conducted before their 14th wedding battle, at relatively close range, from anniversary, are killed in a series of ditches dug into the ground Bosnia and as a result to prevent the opposition from gaining Austria-Hungary declare war any more territory. on Serbia. 1914 1915 1916 1917 1918 1919 November 11, 1918: Four and half years later and the end of July 30, 1914: August 4, 1914: May 7, 1915: the War is finally announced (also referred to as Armistice Day). France and Germany who Great Britain declares war RMS Lusitania, a British ocean liner full of 16 million people had been killed and over 50 million injured; are already fighting over on Germany believing like civillians was sunk by the German army on people’s lives would never be the same again. -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

A Study in American Jewish Leadership

Cohen: Jacob H Schiff page i Jacob H. Schiff Cohen: Jacob H Schiff page ii blank DES: frontis is eps from PDF file and at 74% to fit print area. Cohen: Jacob H Schiff page iii Jacob H. Schiff A Study in American Jewish Leadership Naomi W. Cohen Published with the support of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America and the American Jewish Committee Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England Hanover and London Cohen: Jacob H Schiff page iv Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England, Hanover, NH 03755 © 1999 by Brandeis University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 54321 UNIVERSITY PRESS OF NEW ENGLAND publishes books under its own imprint and is the publisher for Brandeis University Press, Dartmouth College, Middlebury College Press, University of New Hampshire, Tufts University, and Wesleyan University Press. library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Cohen, Naomi Wiener Jacob H. Schiff : a study in American Jewish leadership / by Naomi W. Cohen. p. cm. — (Brandeis series in American Jewish history, culture, and life) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-87451-948-9 (cl. : alk. paper) 1. Schiff, Jacob H. (Jacob Henry), 1847-1920. 2. Jews—United States Biography. 3. Jewish capitalists and financiers—United States—Biography. 4. Philanthropists—United States Biography. 5. Jews—United States—Politics and government. 6. United States Biography. I. Title. II. Series. e184.37.s37c64 1999 332'.092—dc21 [B] 99–30392 frontispiece Image of Jacob Henry Schiff. American Jewish Historical Society, Waltham, Massachusetts, and New York, New York. -

The Divorce of Americans in France

THE DIVORCE OF AMERICANS IN FRANCE LINDYLL T. BATEs* The first French law authorizing divorce a vinculo matrimonii by judgment was enacted in 1792, the very day of the fall of the Bourbon Monarchy. Prior thereto, separation a mensa et thoro alone was countenanced by the strongly clerical King- dom. The rush to divorce under the new liberty was such that in the Year VI of the Republic the number of divorces exceeded that of marriages. The Code Napollon of. x8o3 established divorce for cause and even by mutual consent; though Napoleon's own divorce fron Josephine is the only known instance of the use of a. consent method under the Code. Divorce was abolished in x86 at the reestablishment of the Kingdom, and separation only could be had in France from that time until the Third Republic. The articles of the Civil Coda for divorce based upon cause were reEnacted by Law of July 27, 1884, the articles for divorce by mutual consent remain- ing abolished. With some amendments, this is the law that now governs the insti- tution. Today, divorce.is again frequent in France; separations are but a quarter as numerous. In i885, 4,277 divorces were recorded; in 1913 the figure had risen to 15,372; in 1921, to 2,o33. Now the figure exceeds 30,0o0. The ratio of divorce to population was 70 per hundred thousand in x92; in America it was then x35. About 85 per cent of the divorce petitions are granted. The wife is plaintiff in 65 per cent of the divorce suits.