University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexion Q 2-3

www.ExpressGayNews.com • April 22, 2002 Q1 CYMK COVER STORY Miami Gay and Lesbian Film Festival Highlights By Mary Damiano Treading Water, The Fourth Annual Miami Gay & Thursday, May 2, 7pm Lesbian Film Festival is back, with lots of Casey is in exile from her well-to-do film, premieres, panels and, of course, parties. Catholic family, living just across the bay The festival runs from April 26-May 5, and (but worlds apart) from their pristine will showcase feature films, documentaries, waterfront home, in a tiny house boat that shorts, presentations and panels that will she shares with her girlfriend Alex. But when entertain, inform and excite the expected Christmas rolls around, familial duty calls, audience of 15,000. and even the black sheep must make an All films will be shown at the Colony appearance. Director Lauren Himmel will Theatre, 1040 Lincoln Road, Miami, except attend the screening. A South Florida the opening and closing night films. premiere. Tickets to the film and the post- Here are some highlights of this year’s screening Reel Women reception are $20. film offerings: The Cockettes Tuesday, April 30 7pm An east coast premiere, this film captures The Cockettes, the legendary drag- musical theater phenomenon, and the rarified air of the free-love, acid-dropping, gender- Ruthie and Connie: Every Room in the House Circuit Saturday April 27, 2:30pm bending hippie capital of San Francisco they inhabited in the late 1960s. Features Sylvester Friday, May 3, 9:30pm If Dorothy and Blanche on The Golden Sugar Sweet Dirk Shafer’s hallucinatory new film finds Girls had ever (finally) come out, they’d Saturday, April 27, 9:30pm and Divine, who both appear in the film, along with other notable witnesses to history, such the soul of the circuit and seeks redemption be Ruthie and Connie, the real-life same- Naomi makes lesbian porn. -

Unobtainium-Vol-1.Pdf

Unobtainium [noun] - that which cannot be obtained through the usual channels of commerce Boo-Hooray is proud to present Unobtainium, Vol. 1. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We invite you to our space in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where we encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections by appointment or chance. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Please contact us for complete inventories for any and all collections. The Flash, 5 Issues Charles Gatewood, ed. New York and Woodstock: The Flash, 1976-1979. Sizes vary slightly, all at or under 11 ¼ x 16 in. folio. Unpaginated. Each issue in very good condition, minor edgewear. Issues include Vol. 1 no. 1 [not numbered], Vol. 1 no. 4 [not numbered], Vol. 1 Issue 5, Vol. 2 no. 1. and Vol. 2 no. 2. Five issues of underground photographer and artist Charles Gatewood’s irregularly published photography paper. Issues feature work by the Lower East Side counterculture crowd Gatewood associated with, including George W. Gardner, Elaine Mayes, Ramon Muxter, Marcia Resnick, Toby Old, tattooist Spider Webb, author Marco Vassi, and more. -

University LGBT Centers and the Professional Roles Attached to Such Spaces Are Roughly

INTRODUCTION University LGBT Centers and the professional roles attached to such spaces are roughly 45-years old. Cultural and political evolution has been tremendous in that time and yet researchers have yielded a relatively small field of literature focusing on university LGBT centers. As a scholar-activist practitioner struggling daily to engage in a critically conscious life and professional role, I launched an interrogation of the foundational theorizing of university LGBT centers. In this article, I critically examine the discursive framing, theorization, and practice of LGBT campus centers as represented in the only three texts specifically written about center development and practice. These three texts are considered by center directors/coordinators, per my conversations with colleagues and search of the literature, to be the canon in terms of how centers have been conceptualized and implemented. The purpose of this work was three-fold. Through a queer feminist lens focused through interlocking systems of oppression and the use of critical discourse analysis (CDA) 1, I first examined the methodological frameworks through which the canonical literature on centers has been produced. The second purpose was to identify if and/or how identity and multicultural frameworks reaffirmed whiteness as a norm for LGBT center directors. Finally, I critically discussed and raised questions as to how to interrupt and resist heteronormativity and homonormativity in the theoretical framing of center purpose and practice. Hired to develop and direct the University of Washington’s first lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT2) campus center in 2004, I had the rare opportunity to set and implement with the collaboration of queerly minded students, faculty, and staff, a critically theorized and reflexive space. -

UPDATED KPCC-KVLA-KUOR Quarterly Report JAN-MAR 2013

Date Key Synopsis Guest/Reporter Duration Quarterly Programming Report JAN-MAR 2013 KPCC / KVLA / KUOR 1/1/13 MIL With 195,000 soldiers, the Afghan army is bigger than ever. But it's also unstable. Rod Nordland 8:16 When are animals like humans? More often than you think, at least according to a new movement that links human and animal behaviors. KPCC's Stephanie O'Neill 1/1/13 HEAL reports. Stephanie O'Neill 4:08 We've all heard warning like, "Don't go swimming for an hour after you eat!" "Never run with scissors," and "Chew on your pencil and you'll get lead poisoning," from our 1/1/13 ART parents and teachers. Ken Jennings 7:04 In "The Fine Print," Pulitzer Prize-winning author David Cay Johnston details how the David Cay 1/1/13 ECON U.S. tax system distorts competition and favors corporations and the wealthy. Johnston 16:29 Eddie Izzard joins the show to talk about his series at the Steve Allen Theater, plus 1/1/13 ART he fills us in about his new show, "Force Majeure." Eddie Izzard 19:23 Our regular music critics Drew Tewksbury, Steve Hochman and Josh Kun join Alex Drew Tewksbury, Cohen and A Martinez for a special hour of music to help you get over your New Steve Hochman 1/1/13 ART Year’s Eve hangover. and Josh Kun 12:57 1/1/2013 IMM DREAM students in California get financial aid for state higher ed Guidi 1:11 1/1/2013 ECON After 53 years, Junior's Deli in Westwood has closed its doors Bergman 3:07 1/1/2013 ECON Some unemployed workers are starting off the New Year with more debt Lee 2:36 1/1/2013 ECON Lacter on 2013 predictions -

The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew Hes Ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 "I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew heS ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Ames, Matthew Sheridan, ""I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6150. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

June 4, 5 in 1991, Marchers Were Taunted, Personally Wants to Marry His Part Buffalo's Gay Pride Celebra Chased and Verbally Assaulted

Partnerships The Gay Alliance appreciates the continuing partnership of businesses within our community who support our mission and vision. Platinum: MorganStanley Smith Barney Gold: Met life Silver: Excenus+' lesbians in New York State." NIXON PEA BOOYt1r State representatives Like Buf The outdoor rally in Albany on May 9. Photo: Ove Overmyer. More photos on page 18. falo area Assembly member Sam Hoyt followed Bronson on stage, -f THE JW:HBLDR as well as Manhattan Sen. Tom ftOCHUUII.FORUM lltW tRC Marriage Equality and GENDA get equal billing Duane and Lieutenant Gover .-ew ..A..Ulli.LIItlletil nor Bob Duffy; former mayor of at Equality and Justice Day; marriage bill's Rochester. TOMPKINrS future in Senate is still unclear "Marriage equality is a basic issue of civ.il rights," Duffy told By Ove Overmyer Closet press time, it was unclear a cheering crowd. "Nobody in Bronze: Albany, N.Y. - On May 9, when or if Governor Cuomo chis scare should ever question nearly 1,200 LGBT advocates would introduce the bill in rhe or underestimate Governor Cuo and allies gathered in the Empire Republican-dominated Senate. mo's commitment to marriage equality. The vernorhas made Kodak State Plaza Convention Center He has scared char he will �? underneath the state house in not do so unless there are enough marriage equality one of his top le Albany for what Rochester area voces to pass the legislation. three zislacive issues chis/ear." 0ut�t.W. Assembly member Harry Bron On May 9, activists from Dutfy acknowledge the son called "a historic day." every corner of the state, from difficulties that a marriage bill Assembly member Danny Buffalo to Montauk Pc. -

Sylvia Rivera 7/2/1951 – 2/19/2002

SYLVIA RIVERA 7/2/1951 – 2/19/2002 Gay civil rights pioneer Sylvia Rivera was one of the instigators of the Sylvia Rivera, then a 17-year-old drag queen, was among the crowd that gathered outside the Stonewall Inn the night of June 27, 1969, when the New York police raided Stonewall uprising, an the popular Greenwich Village gay bar. Rivera reportedly shouted, “I’m not missing a event that helped launch minute of this, it’s the revolution!” As the police escorted patrons from the bar, Rivera the modern gay rights was one of the first bystanders to throw a bottle. movement. After Stonewall, Rivera joined the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) and worked energetically on its campaign to pass the New York City Gay Rights Bill. She was famously arrested for climbing the walls of City Hall in a dress and high heels to crash a closed-door meeting on the bill. In time, the GAA eliminated drag and transvestite concerns from their agenda as they sought to broaden their political base. Years later, Rivera told an interviewer, “When things started getting more mainstream, it was like, ‘We don’t need you no more.’ ” She added, “Hell hath no fury like a drag queen scorned.” Born Ray Rivera Mendosa, Sylvia Rivera was a persistent and vocal advocate for transgender rights. Her activist zeal was fueled by her own struggles to find food, shelter and safety in the urban streets from the time she left home at age 10. In 1970, Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson co-founded STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries) to help homeless youth. -

Carta De Peticion De La Cumbre

The Honorable U.S. Senator Marco Rubio The Honorable U.S. Senator Rick Scott 201 South Orange Avenue, Suite 350 716 Hart Senate Office Bldg. Orlando, FL 32801 Washington, DC 20510 April 28, 2021 Re: We Need You to Co-Sponsor the SECURE Act Dear Senators Marco Rubio and Rick Scott, We, the undersigned organizations and Venezuelan, business and faith leaders, media personalities and members of other TPS communities from Haiti and Central America, are writing to urge you to co-sponsor the SECURE Act, which would provide permanent protections to TPS holders from 12 countries, including Venezuela, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. We held a national summit on Saturday April 17, 2021 to support the SECURE Act, which was introduced by Democratic Senator Chris Van Hollen of Maryland. It needs at least one Republican co-sponsor and the support of 10 GOP senators to become law. The average TPS holder has been in the United States for more than 20 years, contributing to the country’s economy and helping rebuild and recover from the pandemic. Many of them are mixed citizen/immigrant families who have purchased homes and opened businesses, paid taxes, attended schools and places of worship. Despite being an integral part of our communities, TPS holders live in a constant state of uncertainty, needing to reapply to the program every 6 to 18 months and pay substantial fees. It is time to end the uncertainty and make these protections permanent so that families and states like Florida can move forward. The designation of TPS for Venezuela brings long-awaited relief, but it is a temporary reprieve. -

Theater: Do Cry for Evita

Political Hollywood Electronic Dance Music The Avengers One Direction More Log in Create Account August 29, 2012 Edition: U.S. FRONT PAGE POLITICS BUSINESS MEDIA CELEBRITY TV COMEDY FOOD STYLE ARTS BOOKS LIVE ALL SECTIONS Entertainment Celebrity TV Political Hollywood Features Hollywood Buzz Videos HOT ON THE BLOG Featuring fresh takes and real-time analysis from Dean Baker Robert L. Borosage HuffPost's signature lineup of contributors John Hillcoat Jeff Madrick HuffPost Social Reading SPONSOR GENERATED POST Michael Giltz GET UPDATES FROM MICHAEL GILTZ Freelance writer Like 102 Theater: Do Cry for Evita Posted: 04/11/2012 2:42 pm React Inspiring Funny Hot Scary Outrageous Amazing Weird Crazy Follow Video , Andrew Lloyd Webber , Eva Peron , New York Around Town , Ricky Martin , Tim Rice , Broadway , Broadway Musicals , Elena Roger , Evita , Evita Broadway , Evita Broadway Revival , Musicals , Entertainment News Help Us Write 'The Words' EVITA * 1/2 out of **** Quick Read | Comments (26) | 08.20.2012 SHARE THIS STORY MARQUIS THEATRE Broadway fans can go see Jesus Christ Superstar and Evita back to back and appreciate anew how the team of Get Entertainment Alerts FOLLOW US Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice were growing by Sign Up leaps and bounds even as their collaboration was coming to an end. (They reunited over the years, including Submit this story writing some songs for a London production of The MOST POPULAR ON HUFFPOST 1 of 2 Wizard Of Oz that opened last year.) Compared to Superstar, this musical about the life of Eva Peron is the height of sophistication, though Rice's lyrics Isaac Balloons Into A remain blunt and banal. -

U Au S a Ace As

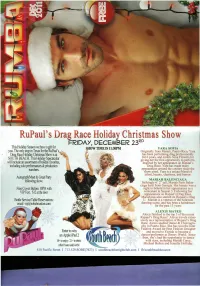

u au s a ace i ay C is as F'RIDAY, DECEM13ER 23RD This Holiday Season we have a gift for SHOW TIME IS 11:30PM YARA SOFIA you. The only stop in Texas for the'RuPaul' s Originally from Manati, Puerto Rico, Yara Drag Race HolieayChris1mas Show is at has been performing drag professionally for 6 years, and credits Nina Flowers for sourn BEACH. This Holiday S~cu1ar giving her the first opportunity to perform. will include an assortment of holiday favorites, Inspired by her appearance on Rupaul's including solo performances & production Drag Race, Yara has made many numbers. appearances around the country since the show aired. Yara is a unique blend of talent, beauty, charisma, and humor. AutographIMeet & Greet Party MARIAH BALENCIAGA following show. Strikingly 6' 2" tall, Mariah Paris Balen- ciaga hails from Georgia. Her beauty was a Free Cover Before 10PM with sight to behold in her appearances as a VIPText. $12 atthe door contestant in Season 3. Following her appearances on Rupaul' s Drag Race, Mariah has also starred on Rupaul's Drag Bottle ServicelTable Reservations: U. Mariah is a veteran of the ballroom email [email protected] dancing scene, and has been a hairdresser for the past 13 years. ALEXIS MATEO Alexis finished in the top 3 of the recent Rupaul's Drag Race! Alexis travels exten- sively as a representative ofRupaul's Drag Race. Alexis studied Dance & Choreogra- phy in Puerto Rico. She has won the Inter Fashion Award for Best Fashion Designer Enter to win and moved to Florida to become a an Apple iPad2 dancer/performer at Disney World. -

Chatting with Evita's Christina Decicco, the 'Alternate Eva'

Friday, June 29, 2012 DIVA TALK Chatting With Evita’s Christina DeCicco, the ‘Alternate Eva’ By ANDREW GANS For those like myself who like to catch as many different actresses playing the role of Evita as possible, there is some exciting news: For two weeks this summer former Wicked star Christina DeCicco will step into the title role of the Tony Award-nominated Broadway revival of the Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice musical at the Marquis Theatre. DeCicco, who normally performs the role twice weekly — Wednesday evenings and Saturday matinees — will play the late Eva Peron six performances a week July 12-19 and August (dates to be announced shortly) while Argentinian actress and Olivier winner Elena Roger films a movie (during those two weeks Jessica Lea Patty will be the Alternate Eva). (For the record, this diva lover has enjoyed the Evitas of Tony winner Patti LuPone, Derin Altay, Nancy Opel, Donna Marie Elio [now Asbury], Judy McLane, Natalie Toro, Felicia Finley, Elena Roger, and, come July 7, Ms. DeCicco.) Although DeCicco has only gotten to play the role about 20 times, her co-stars have lavished her with praise. Rachel Potter, who plays Peron’s Mistress, previously told me, “Christina is from New York. She’s an American through and through, and she brings such a different energy, but it’s so, so great, and I hope that more and more people will come see her because she’s fantastic....Her voice is stunning, and we’re all very, very proud of her because obviously being an alternate is never an easy job. -

Andy Warhol¬タルs Deaths and the Assembly-Line Autobiography

OCAD University Open Research Repository Faculty of Liberal Arts & Sciences and School of Interdisciplinary Studies 2011 Andy Warhol’s Deaths and the Assembly-Line Autobiography Charles Reeve OCAD University [email protected] © University of Hawai'i Press | Available at DOI: 10.1353/bio.2011.0066 Suggested citation: Reeve, Charles. “Andy Warhol’s Deaths and the Assembly-Line Autobiography.” Biography 34.4 (2011): 657–675. Web. ANDY WARHOL’S DEATHS AND THE ASSEMBLY-LINE AUTOBIOGRAPHY CHARLES REEVE Test-driving the artworld cliché that dying young is the perfect career move, Andy Warhol starts his 1980 autobiography POPism: The Warhol Sixties by refl ecting, “If I’d gone ahead and died ten years ago, I’d probably be a cult fi gure today” (3). It’s vintage Warhol: off-hand, image-obsessed, and clever. It’s also, given Warhol’s preoccupation with fame, a lament. Sustaining one’s celebrity takes effort and nerves, and Warhol often felt incapable of either. “Oh, Archie, if you would only talk, I wouldn’t have to work another day in my life,” Bob Colacello, a key Warhol business functionary, recalls the art- ist whispering to one of his dachshunds: “Talk, Archie, talk” (144). Absent a talking dog, maybe cult status could relieve the pressure of fame, since it shoots celebrities into a timeless realm where their notoriety never fades. But cults only reach diehard fans, whereas Warhol’s posthumously pub- lished diaries emphasize that he coveted the stratospheric stardom of Eliza- beth Taylor and Michael Jackson—the fame that guaranteed mobs wherever they went. (Reviewing POPism in the New Yorker, Calvin Tomkins wrote that Warhol “pursued fame with the single-mindedness of a spawning salmon” [114].) Even more awkwardly, cult status entails dying—which means either you’re not around to enjoy your notoriety or, Warhol once nihilistically pro- posed, you’re not not around to enjoy it.