The Wiretapping of Things

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyber Threats to Mobile Phones Paul Ruggiero and Jon Foote

Cyber Threats to Mobile Phones Paul Ruggiero and Jon Foote Mobile Threats Are Increasing Smartphones, or mobile phones with advanced capabilities like those of personal computers (PCs), are appearing in more people’s pockets, purses, and briefcases. Smartphones’ popularity and relatively lax security have made them attractive targets for attackers. According to a report published earlier this year, smartphones recently outsold PCs for the first time, and attackers have been exploiting this expanding market by using old techniques along with new ones.1 One example is this year’s Valentine’s Day attack, in which attackers distributed a mobile picture- sharing application that secretly sent premium-rate text messages from the user’s mobile phone. One study found that, from 2009 to 2010, the number of new vulnerabilities in mobile operating systems jumped 42 percent.2 The number and sophistication of attacks on mobile phones is increasing, and countermeasures are slow to catch up. Smartphones and personal digital assistants (PDAs) give users mobile access to email, the internet, GPS navigation, and many other applications. However, smartphone security has not kept pace with traditional computer security. Technical security measures, such as firewalls, antivirus, and encryption, are uncommon on mobile phones, and mobile phone operating systems are not updated as frequently as those on personal computers.3 Mobile social networking applications sometimes lack the detailed privacy controls of their PC counterparts. Unfortunately, many smartphone users do not recognize these security shortcomings. Many users fail to enable the security software that comes with their phones, and they believe that surfing the internet on their phones is as safe as or safer than surfing on their computers.4 Meanwhile, mobile phones are becoming more and more valuable as targets for attack. -

Electronic Communications Surveillance

Electronic Communications Surveillance LAUREN REGAN “I think you’re misunderstanding the perceived problem here, Mr. President. No one is saying you broke any laws. We’re just saying it’s a little bit weird that you didn’t have to.”—John Oliver on The Daily Show1 The government is collecting information on millions of citizens. Phone, Internet, and email habits, credit card and bank records—vir- tually all information that is communicated electronically is subject to the watchful eye of the state. The government is even building a nifty, 1.5 million square foot facility in Utah to house all of this data.2 With the recent exposure of the NSA’s PRISM program by whistleblower Edward Snowden, many people—especially activists—are wondering: How much privacy do we actually have? Well, as far as electronic pri- vacy, the short answer is: None. None at all. There are a few ways to protect yourself, but ultimately, nothing in electronic communications is absolutely protected. In the United States, surveillance of electronic communications is governed primarily by the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (ECPA), which is an extension of the 1968 Federal Wiretap act (also called “Title III”) and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). Other legislation, such as the USA PATRIOT Act and the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA), sup- plement both the ECPA and FISA. The ECPA is divided into three broad areas: wiretaps and “electronic eavesdropping,” stored messages, and pen registers and trap-and-trace devices. Each degree of surveillance requires a particular burden that the government must meet in order to engage in the surveillance. -

Image Steganography Applications for Secure Communication

IMAGE STEGANOGRAPHY APPLICATIONS FOR SECURE COMMUNICATION by Tayana Morkel Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science (Computer Science) in the Faculty of Engineering, Built Environment and Information Technology University of Pretoria, Pretoria May 2012 © University of Pretoria Image Steganography Applications for Secure Communication by Tayana Morkel E-mail: [email protected] Abstract To securely communicate information between parties or locations is not an easy task considering the possible attacks or unintentional changes that can occur during communication. Encryption is often used to protect secret information from unauthorised access. Encryption, however, is not inconspicuous and the observable exchange of encrypted information between two parties can provide a potential attacker with information on the sender and receiver(s). The presence of encrypted information can also entice a potential attacker to launch an attack on the secure communication. This dissertation investigates and discusses the use of image steganography, a technology for hiding information in other information, to facilitate secure communication. Secure communication is divided into three categories: self-communication, one-to-one communication and one-to-many communication, depending on the number of receivers. In this dissertation, applications that make use of image steganography are implemented for each of the secure communication categories. For self-communication, image steganography is used to hide one-time passwords (OTPs) in images that are stored on a mobile device. For one-to-one communication, a decryptor program that forms part of an encryption protocol is embedded in an image using image steganography and for one-to-many communication, a secret message is divided into pieces and different pieces are embedded in different images. -

Espionage Against the United States by American Citizens 1947-2001

Technical Report 02-5 July 2002 Espionage Against the United States by American Citizens 1947-2001 Katherine L. Herbig Martin F. Wiskoff TRW Systems Released by James A. Riedel Director Defense Personnel Security Research Center 99 Pacific Street, Building 455-E Monterey, CA 93940-2497 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704- 0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DDMMYYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From – To) July 2002 Technical 1947 - 2001 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER 5b. GRANT NUMBER Espionage Against the United States by American Citizens 1947-2001 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER Katherine L. Herbig, Ph.D. Martin F. Wiskoff, Ph.D. 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. -

The Usa Patriot Act Sunset Extension Act of 2011

Calendar No. 18 112TH CONGRESS REPORT " ! 1st Session SENATE 112–13 THE USA PATRIOT ACT SUNSET EXTENSION ACT OF 2011 APRIL 5, 2011.—Ordered to be printed Mr. LEAHY, from the Committee on the Judiciary, submitted the following R E P O R T together with MINORITY VIEWS [To accompany S. 193] [Including cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office] The Committee on the Judiciary, to which was referred the bill (S. 193), to extend the sunset of certain provisions of the USA PA- TRIOT Act and the authority to issue national security letters, and for other purposes, having considered the same, reports favorably thereon, with amendments, and recommends that the bill, as amended, do pass. CONTENTS Page I. Background and Purpose of The USA PATRIOT Act Sunset Extension Act of 2011 .................................................................................................. 2 II. History of the Bill and Committee Consideration ....................................... 20 III. Section-by-Section Summary of the Bill ...................................................... 22 IV. Congressional Budget Office Cost Estimate ................................................ 27 V. Regulatory Impact Evaluation ...................................................................... 31 VI. Conclusion ...................................................................................................... 31 VII. Minority Views ............................................................................................... 32 VIII. Changes to Existing Law Made -

The Notice Problem, Unlawful Electronic Surveillance, and Civil Liability Under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act

University of Miami Law Review Volume 61 Number 2 Volume 61 Number 2 (January 2007) Article 5 1-1-2007 The Notice Problem, Unlawful Electronic Surveillance, and Civil Liability Under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act Andrew Adler Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Andrew Adler, The Notice Problem, Unlawful Electronic Surveillance, and Civil Liability Under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, 61 U. Miami L. Rev. 393 (2007) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol61/iss2/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES The Notice Problem, Unlawful Electronic Surveillance, and Civil Liability Under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act ANDREW ADLER* I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................... 393 II. ORIGIN AND BASIC FRAMEWORK OF FISA ............................... 399 III. THE NOTICE PROBLEM ................................................ 404 IV. ERRORS IN THE FISA PROCESS ......................................... 408 A. Application Process .............................................. 408 B. Implementation Process ........................................... 412 1. INTERNAL FBI COMMUNICATIONS: -

THE BRIDGE BETWEEN the WAR on DRUGS and the WAR on TERRORISM Gerald G. Ashdown* the Reaction to The

THE BLUEING OF AMERICA: THE BRIDGE BETWEEN THE WAR ON DRUGS AND THE WAR ON TERRORISM Gerald G. Ashdown* I. INTRODUCTION The reaction to the Vietnam War protest years, the presidency of Richard Nixon, and ultimately that of Ronald Reagan, ushered in a conservative revolution in the United States that still endures. Republican Presidents during this period have appointed eleven Justices to the United States Supreme Court,1 seven of whom serve on the Court today.2 Coinciding with this historical phenomenon was the proliferation of drug usage in the country: first marijuana, hallucinogenic drugs, and amphetamines during the counterculture years of the late ’60s and ’70s, and later powder and then crack cocaine. When prosecutorial emphasis shifted, especially at the federal level,3 to meet the increased fascination with narcotics, courts in the country became deluged with drug cases, many if not most of which presented Fourth Amendment search and seizure issues. This, of course, was because the Fourth Amendment’s exclusionary rule could make the corpus of the crime unavailable to the prosecution.4 Due to the presence of this important Fourth Amendment issue in drug prosecutions, both state and federal, a significant number of these cases found their way to the United States Supreme Court for review. In most of these cases, the Court did not disappoint the Republican Presidents who had appointed a majority of the Justices. Under the tutelage of Chief Justices * James A. “Buck” & June M. Harless Professor of Law, West Virginia University College of Law. 1. Justices Blackmun, Powell, and Rehnquist were appointed by Richard M. -

Image Steganography: Protection of Digital Properties Against Eavesdropping

Image Steganography: Protection of Digital Properties against Eavesdropping Ajay Kumar Shrestha Ramita Maharjan Rejina Basnet Computer and Electronics Engineering Computer and Electronics Engineering Computer and Electronics Engineering Kantipur Engineering College, TU Kantipur Engineering College, TU Kantipur Engineering College, TU Lalitpur, Nepal Lalitpur, Nepal Lalitpur, Nepal [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—Steganography is the art of hiding the fact that Data encryption is basically a strategy to make the data communication is taking place, by hiding information in other unreadable, invisible or incomprehensible during transmission information. Different types of carrier file formats can be used, by scrambling the content of data. Steganography is the art but digital images are the most popular ones because of their and science of hiding information by embedding messages frequency on the internet. For hiding secret information in within seemingly harmless messages. It also refers to the images, there exists a large variety of steganography techniques. “Invisible” communication. The power of Steganography is in Some are more complex than others and all of them have hiding the secret message by obscurity, hiding its existence in respective strong and weak points. Many applications may a non-secret file. Steganography works by replacing bits of require absolute invisibility of the secret information. This paper useless or unused data in regular computer files. This hidden intends to give an overview of image steganography, it’s uses and information can be plaintext or ciphertext and even images. techniques, basically, to store the confidential information within images such as details of working strategy, secret missions, According to Bhattacharyya et al., “Steganography’s niche in criminal and confidential information in various organizations security is to supplement cryptography, not replace it. -

The Federal Bureau of Investigation and Terrorism Investigations

The Federal Bureau of Investigation and Terrorism Investigations Jerome P. Bjelopera Specialist in Organized Crime and Terrorism April 24, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41780 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Federal Bureau of Investigation and Terrorism Investigations Summary The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI, the Bureau) is the lead federal law enforcement agency charged with counterterrorism investigations. Since the September 11, 2001 (9/11) attacks, the FBI has implemented a series of reforms intended to transform itself from a largely reactive law enforcement agency focused on investigations of criminal activity into a more proactive, agile, flexible, and intelligence-driven agency that can prevent acts of terrorism. This report provides background information on key elements of the FBI terrorism investigative process based on publicly available information. It discusses • several enhanced investigative tools, authorities, and capabilities provided to the FBI through post-9/11 legislation, such as the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001; the 2008 revision to the Attorney General’s Guidelines for Domestic FBI Operations (Mukasey Guidelines); and the expansion of Joint Terrorism Task Forces (JTTF) throughout the country; • intelligence reform within the FBI and concerns about the progress of those reform initiatives; • the FBI’s proactive, intelligence-driven posture in its terrorism investigations using preventative policing techniques such as the “Al Capone” approach and the use of agent provocateurs; and • the implications for privacy and civil liberties inherent in the use of preventative policing techniques to combat terrorism. This report sets forth possible considerations for Congress as it executes its oversight role. -

Reviving Telecommunications Surveillance Law Paul M

Reviving Telecommunications Surveillance Law Paul M. Schwartz t INTRODUCTION Consider three questions. How would one decide if there was too much telecommunications surveillance in the United States or too lit- tle? How would one know if law enforcement was using its surveil- lance capabilities in the most effective fashion? How would one assess the impact of this collection of information on civil liberties? In answering these questions, a necessary step, the logical first move, would be to examine existing data about governmental surveil- lance practices and their results. One would also need to examine and understand how the legal system generated these statistics about tele- communications surveillance. To build on Patricia Bellia's scholarship, we can think of each telecommunications surveillance statute as hav- ing its own "information structure."' Each of these laws comes with institutional mechanisms that generate information about use of the respective statute.2 Ideally, the information structure would generate data sets that would allow the three questions posed above to be an- swered. Light might also be shed on other basic issues, such as whether or not the amount of telecommunications surveillance was increasing or decreasing. Such rational inquiry about telecommunications surveillance is, however, largely precluded by the haphazard and incomplete informa- tion that the government collects about it. In Heart of Darkness,3 Jo- seph Conrad has his narrator muse on the "blank spaces" on the globe. Marlowe says: Now when I was a little chap I had a passion for maps.... At that time there were many blank spaces on the earth, and when I saw t Professor of Law, UC Berkeley School of Law, Director, Berkeley Center for Law and Technology. -

The Fourth Amendment's National Security Exception: Its History and Limits L

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 66 | Issue 5 Article 1 10-2013 The ourF th Amendment's National Security Exception: Its History and Limits L. Rush Atkinson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Fourth Amendment Commons Recommended Citation L. Rush Atkinson, The ourF th Amendment's National Security Exception: Its History and Limits, 66 Vanderbilt Law Review xi (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol66/iss5/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Fourth Amendment's National Security Exception: Its History and Limits L. Rush Atkinson 66 Vand. L. Rev. 1343 (2013) Each year, federal agents conduct thousands of "national security investigations" into suspected spies, terrorists, and other foreign threats. The constitutional limits imposed by the Fourth Amendment, however, remain murky, and the extent to which national security justifies deviations from the Amendment's traditional rules is unclear. With little judicial precedent on point, the gloss of past executive practice has become an important means for gauging the boundaries of today's national security practices. Accounts of past executive practice, however, have thus far been historically incomplete, leading to distorted analyses of its precedential significance. Dating back to World War II, national security investigations have involved warrantless surveillance and searches-conduct clearly impermissible in the traditional law-enforcement context- authorized under the theory of a "national security" or "foreign intelligence" exception to the Fourth Amendment. -

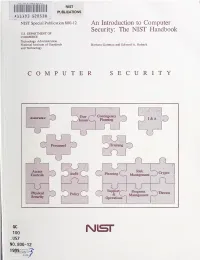

An Introduction to Computer Security: the NIST Handbook U.S

HATl INST. OF STAND & TECH R.I.C. NIST PUBLICATIONS AlllOB SEDS3fl NIST Special Publication 800-12 An Introduction to Computer Security: The NIST Handbook U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Technology Administration National Institute of Standards Barbara Guttman and Edward A. Roback and Technology COMPUTER SECURITY Contingency Assurance User 1) Issues Planniii^ I&A Personnel Trairang f Access Risk Audit Planning ) Crypto \ Controls O Managen»nt U ^ J Support/-"^ Program Kiysfcal ~^Tiireats Policy & v_ Management Security Operations i QC 100 Nisr .U57 NO. 800-12 1995 The National Institute of Standards and Technology was established in 1988 by Congress to "assist industry in the development of technology . needed to improve product quality, to modernize manufacturing processes, to ensure product reliability . and to facilitate rapid commercialization ... of products based on new scientific discoveries." NIST, originally founded as the National Bureau of Standards in 1901, works to strengthen U.S. industry's competitiveness; advance science and engineering; and improve public health, safety, and the environment. One of the agency's basic functions is to develop, maintain, and retain custody of the national standards of measurement, and provide the means and methods for comparing standards used in science, engineering, manufacturing, commerce, industry, and education with the standards adopted or recognized by the Federal Government. As an agency of the U.S. Commerce Department's Technology Administration, NIST conducts basic and applied research in the physical sciences and engineering, and develops measurement techniques, test methods, standards, and related services. The Institute does generic and precompetitive work on new and advanced technologies. NIST's research facilities are located at Gaithersburg, MD 20899, and at Boulder, CO 80303.