Perceptions of Mexican Cuisine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPETIZERS Homemade SOUPS Desserts SPECIALTY TACOS

(575) 527-0817 1551 Amador Ave. Las Cruces, NM 88001 Sergio Castillo - Restaurant Manager Open Everyday 11:00am to 8:00pm www.sisenor.com APPETIZERS HOMEMADE SOUPS Bowl of soup M-F- $7.49 Upgrade to Large Soup - $1.99 Nachos .......................................................................... $9.59 Homemade corn tortilla chips topped with beans, taco meat, and Monday – Chicken and Rice Soup melted cheese. Lettuce, tomatoes and jalapeños upon request. Tuesday – Caldillo (Green Chile Beef Stew) Wednesday – Albondigas (Meatballs with Rice) Nachitos .....................................................................................$8.89 Thursday – Fideos (Vermicelli with Beef) Homemade corn tortilla chips topped with beans Friday – Cod Fish & Shrimp Soup w/ Vegetables & side of Rice and melted cheese. Saturday & Sunday Menudo - $7.79 Si Señor Wings ...........................................................$10.39 Caldo de Res - $8.09 (Vegetable Beef Soup & side of rice) Get these great wings slightly battered, perfectly cooked and Posole Fresh Daily - $7.69 served with a side of spicy BBQ sauce and ranch. Seasonal (Nov-Feb) Chile Cheese Fries ...............................................................$8.89 French fries smothered with cheese and your choice of red LITTLE ONES MENU or green chile. (12 years or younger only) ................................................................... Taco Plate ................................................................................... $6.39 House Sampler $10.59 One beef or chicken -

APPETIZERS Homemade SOUPS SPECIALTY TACOS LITTLE ONES

(575) 527-0817 1551 Amador Ave., Las Cruces, NM 88001 Sergio Castillo - Restaurant Manager Open Everyday 11:00am to 8:00pm www.sisenor.com APPETIZERS HOMEMADE SOUPS Nachos ........................................................................$10.50 Bowl of soup M-F- $7.49 Upgrade to Large Soup - $1.99 handmade corn tortilla chips topped with refried beans, our signature queso, freshly grated Monterey Jack and cheddar Monday – Chicken and Rice Soup cheese, your choice of ground beef, shredded beef, or shredded Tuesday – Caldillo (Green Chile Beef Stew) chicken. Lettuce, tomatoes, and jalapeño upon request. Wednesday – Albondigas (Meatballs with Rice) Add carne asada or al pastor ..................................................$2.50 Thursday – Fideos (Vermicelli with Beef) Friday – Cod Fish & Shrimp Soup w/ Vegetables & side of Rice Si Señor Wings ................................................................ $11 Get these great wings slightly battered, perfectly cooked and Saturday & Sunday served with a side of spicy BBQ sauce and ranch. Menudo - $7.79 Caldo de Res - $8.09 (Vegetable Beef Soup & side of rice) Chile Cheese Fries ...............................................................$8.89 Posole Fresh Daily - $7.69 French fries with your choice of chile topped with melted, freshly Seasonal (Nov-Feb) grated Monterrey Jack and cheddar cheese. Asada or Al Pastor fries ................................................ $12 Crispy French fries topped with our signature queso, freshly LITTLE ONES MENU grated Monterey Jack and cheddar -

Picos Restaurant Dinner Menu (As of 12-07-2016)

OFREGIONS MEXICAN CUISINE Ceviches APPETIZERS PESCADOR 12 **NAMED TEXAS MONTHLY Top 10 TACO In Texas** SEAFOOD AL AJILLO Lime-marinated Fisherman’s ceviche with fresh Chilorio 12 Your choice of seafood pan sautéed in olive oil infused snapper, Gulf shrimp or combo, tossed with onions, Sinaloa-style slow roasted seasoned pulled pork served with fresh garlic, pasilla and arbol peppers served with tomatoes, serrano peppers, cilantro and avocado with avocado slices, pico de gallo and fresh tortillas toasted bolillo bread SHRIMP 16 Campechano 13 Tamales Oaxaqueños 15 Lime-marinated fresh snapper, Gulf shrimp or combo, Three banana leaf-wrapped tamales - pork, chicken and Octopus 16 tossed with onions, tomatoes, cilantro, serrano peppers, portobello with cuitlacoche CALAMARI 14 avocado and fresh campechana sauce Nachos Jorge 12 NAPOLEÓN WITH 13 Cochinita pibil, Chihuahua cheese, marinated red CALAMARI Mexicana 14 onions, jalapeños, guacamole, and refried black beans Fresh calamari sautéed with fresh tomatoes, onions, serrano PINEAPPLE AND MANGO PICO peppers and cilantro, served with toasted bolillo bread Tower of lime-marinated fresh snapper, Gulf shrimp or combo layered with pineapple and mango pico, tomatoes Queso Flameado 12 Mariscada a la Mex 20 and avocado Melted Chihuahua cheese topped with house-made chorizo or sautéed mushrooms and poblano peppers Gulf shrimp, fresh calamari, crawfish tails, mussels and red snapper sautéed with onions, peppers, cilantro and VUELVE A LA VIDA COCKTAIL* 19 tomatoes, served with toasted bolillo bread Gulf -

Was the Taco Invented in Southern California?

investigations | jeffrey m. pilcher WWasas thethe TacoTaco InventedInvented iinn SSouthernouthern CCalifornia?alifornia? Taco bell provides a striking vision of the future trans- literally shape social reality, and this new phenomenon formation of ethnic and national cuisines into corporate that the taco signified was not the practice of wrapping fast food. This process, dubbed “McDonaldization” by a tortilla around morsels of food but rather the informal sociologist George Ritzer, entails technological rationaliza- restaurants, called taquerías, where they were consumed. tion to standardize food and make it more efficient.1 Or as In another essay I have described how the proletarian taco company founder Glen Bell explained, “If you wanted a shop emerged as a gathering place for migrant workers from dozen [tacos]…you were in for a wait. They stuffed them throughout Mexico, who shared their diverse regional spe- first, quickly fried them and stuck them together with a cialties, conveniently wrapped up in tortillas, and thereby toothpick. I thought they were delicious, but something helped to form a national cuisine.4 had to be done about the method of preparation.”2 That Here I wish to follow the taco’s travels to the United something was the creation of the “taco shell,” a pre-fried States, where Mexican migrants had already begun to create tortilla that could be quickly stuffed with fillings and served a distinctive ethnic snack long before Taco Bell entered the to waiting customers. Yet there are problems with this scene. I begin by briefly summarizing the history of this food interpretation of Yankee ingenuity transforming a Mexican in Mexico to emphasize that the taco was itself a product peasant tradition. -

Botanas (Appetizers)

Salsa Macha GF Botanas (Appetizers) chile de arbol and garlic roasted to a nutty, spicy, crumbly salsa, served with queso Cochinita Pibil GF fresco, avocado and mini tortillas (spice up any entrée!) marinated pork in an achiote recipe, slowly roasted until tender, served wrapped in Shrimp Jalapeño Poppers three lightly seared mini tortillas, topped with seasoned marinated onions and mexican three tiger prawn shrimp stuffed with a hint of our house blend cheese, wrapped in crema 9 bacon, grilled jalapeño fried in beer batter, served with our chipotle cream sauce 15 Quesadilla Mini Empanaditas GF flour or corn masa tortillas with melted house blend oaxaca cheese, served with melted house blend oaxaca cheese with a jalapeño slice, or shrimp and chorizo topped guacamole, pico de gallo and sour cream 11 with crema and queso cotija, three empanaditas 9, six empanaditas 18 Add Shredded Chicken, Shredded Beef, Grilled Chicken, Carnitas, Chicken Tinga, Carne Asada, Sautéed Veggies or Shrimp 2 Guacamole GF avocado, tomatoes, onions, cilantro, jalapeños and fresh limes, topped with queso Quesadilla de Chipotle GF fresco and crispy tortillas 11 / 18 fresh corn masa with chipotle, filled with melted house blend oaxaca cheese, stuffed Add Shrimp or Crab Seared in Abuelo Spicy Sauce 2 with choice of sautéed veggies or black beans, served with pico de gallo, guacamole and sour cream 10 Queso Fundido GF Sopas y Ensaladas mexican blend of traditional oaxaca cheese melted in a cast iron pan, served with Sopa de Fideo choice of flour or corn mini tortillas -

Descendants of the Anusim (Crypto-Jews) in Contemporary Mexico

Descendants of the Anusim (Crypto-Jews) in Contemporary Mexico Slightly updated version of a Thesis for the degree of “Doctor of Philosophy” by Schulamith Chava Halevy Hebrew University 2009 © Schulamith C. Halevy 2009-2011 This work was carried out under the supervision of Professor Yom Tov Assis and Professor Shalom Sabar To my beloved Berthas In Memoriam CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................7 1.1 THE PROBLEM.................................................................................................................7 1.2 NUEVO LEÓN ............................................................................................................ 11 1.2.1 The Original Settlement ...................................................................................12 1.2.2 A Sephardic Presence ........................................................................................14 1.2.3 Local Archives.......................................................................................................15 1.3 THE CARVAJAL TRAGEDY ....................................................................................... 15 1.4 THE MEXICAN INQUISITION ............................................................................. 17 1.4.1 José Toribio Medina and Alfonso Toro.......................................................17 1.4.2 Seymour Liebman ...............................................................................................18 1.5 CRYPTO‐JUDAISM -

Recetas Para El Dia De Muertos

Recetas para el Día de Muertos La comida y la bebida juegan un papel muy importante en las festividades del Día de Muertos. Son ofrendas, que se colocan en los altares para persuadir a los seres queridos y que no regresen o visiten la tierra de los vivos. Para honrar aún más a nuestros antepasados, comemos con ellos, celebrando con alegría y conmemorando las vidas que vivieron. Hemos recopilado recetas de algunos de los platos y bebidas más populares que se preparan para el Día de Muertos. ¡Esperamos que disfrute compartiéndolos con sus seres queridos! Agua de Horchata Tiempo de preparacin: 15 minutos Servings: 6-8 glasses Ingredientes • 3 cucharadas de arroz blanco de grano largo • 1 ramita de canela • 6 tazas de agua • 3 cucharadas de azcar • ½ taza de leche Agua de Horchata es una bebida tradicional elaborada con arroz y agua. Se endulza y se sirve frío. Instrucciones 1. En un tazn grande, combine el arroz, las ramas de canela y la leche. 2. Calentar la mezcla hasta justo antes de que hierva. 3. Transfera la mezcla a una licuadora. Procese hasta que quede suave. 4. Vierta la mezcla en un frasco grande. Agrega azcar y agua. 5. Sirva sobre hielo o enfríe hasta el momento de servir. Champurrado Tiempo de preparacin + coccin: 35 minutos Porciones: 12 Ingredientes • 1 ½ tazas de agua • 1 rama de canela • 4 a 6 clavos enteros • 1 vaina de anís estrellado • 4 ¼ tazas de leche • 2 barras de chocolate • mexicano (la marca Abuelita está disponible en la mayoría de las tiendas de comestibles) • ¾ taza de harina de maíz mol- ida gruesa (la marca Maseca está disponible en la mayoría de las tiendas de comestibles) • 1 pizca de piloncillo triturado o más al gusto. -

Menu Specials

Ácenar’s New Year’s Eve MENU SPECIALS SERVED 11 AM - 10:30 PM Antojitos Appetizer Sampler 19.95 A sampling of our chicken flautas, beef alambres and quesadillas served with pico de gallo and guacamole Shrimp Cocktail 13.95 Large shrimp, spicy house-made cocktail sauce, onions, cilantro, avocados Jicama Shrimp Tacos 13.50 Gulf shrimp sautéed and served on jicama with tamarindo sauce and crispy leeks Short Rib Nachos 13.25 Guajillo braised short ribs, refried beans, cheddar cheese Ostiones / Oysters 13.25 Buttermilk-fried oysters on yucca chips, jalapeño honey mayo and charred pineapple Guacamole 12.95 Served with house-made chips Copitas / Lettuce Cups 12.50 Chicken & pork stewed with chipotle, chile arbol & tamarindo in lettuce cups with salsa trio & roasted cashews Alambres / Mini Skewers 11.25 Marinated beef skewers drizzled with chimichurri salsas on a bed of cilantro slaw Ceviche / Lime Marinated Fish 11.25 Lime-marinated fish served with house-made chips and sliced avocado Queso Flameado / Baked Cheese 10.25 Chihuahua and Monterey Jack cheeses, mushrooms, chorizo, grilled onions and peppers Sopas y Ensaladas Ensalada Ácenar / Chef Salad 14.95 Bibb salad, queso fresco, roasted corn, grilled poblanos, avocados and jicama served with your choice of chicken or beef fajitas or two large grilled shrimp with chipotle ranch dressing on the side Pozole Rojo 9.25 Guajillo seasoned broth, hominy and green cabbage choice of chicken or pork Sopa Azteca / Tortilla Soup 8.25 Grilled chicken in a chile pasilla and tomato-spiced broth, topped with -

G R O U P D I N I

GROUP DINING SCOTTSDALE WELCOME TO TOCA MADERA Thank you for choosing Toca Madera for your event! Toca has proven to be a world-class venue for private events and we are delighted to take you on a quick tour of everything we have to offer. Whether for a company gathering, holiday party, bridal or baby shower, product launch, charity gala, or a myriad of other occasions, Toca Madera delivers a stunning venue with unparalleled culinary, beverage, and entertainment programming. Welcome to our world. DINING OPTIONS MENU OPTION ONE $65 per person STARTERS SALADS Included: Select one of the following: GUACAMOLE (Vg) TOCA CAESAR organic avocado, pomegranate seeds, lime pepitas, red onion, jalapeño, organic red leaf romaine, pepita seeds, garlic herb bread crumble, truffle cilantro, served w/ warm house-made plantain chips manchego cheese, house-made dressing *tortilla chips available upon request *vegan parmesan (Vg) SALSA FLIGHT (Vg) MEXICAN FATTOUSH warm corn tortilla chips w/ avocado tomatillo salsa, tres chile salsa, organic hearts of romaine, cherry tomato, radish, tajin blue corn tortilla, habanero salsa queso fresco, red onion, cilantro, micro tangerine, roasted ancho & cortez sea salt vinaigrette Select one of the following: *vegan parmesan (Vg) VEGAN CEVICHE (Vg) hearts of palm, lime, serrano, baby heirloom tomatoes, shaved coconut, ENTREES mango Select two of the following: TOSTADITAS CHEF’S ENCHILADAS five house-made crispy corn tortillas, black beans, queso fresco, butter shredded organic free-range chicken, oaxacan queso, soft corn -

Food Blogging in Los Angeles, the Life and Times of Javier Cabral: an Interview

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Via Sapientiae: The Institutional Repository at DePaul University Diálogo Volume 18 Number 1 Article 16 2015 Food Blogging in Los Angeles, the Life and Times of Javier Cabral: An Interview Gabriel Chabrán Echternacht Whittier College Javier Cabral Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo Part of the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Chabrán Echternacht, Gabriel and Cabral, Javier (2015) "Food Blogging in Los Angeles, the Life and Times of Javier Cabral: An Interview," Diálogo: Vol. 18 : No. 1 , Article 16. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo/vol18/iss1/16 This Interview is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Latino Research at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Diálogo by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Food Blogging in Los Angeles, the Life and Times of Javier Cabral: An Interview Gabriel Chabrán Echternacht Whittier College INTRODUCTION avier Cabral is a reporter who specializes in food West Side of L.A., and he had the money to take me out Jculture and punk rock. He was born in East Los to expensive restaurants at first. I started realizing that Angeles, California, in 1989 and grew up in the San this happened at the same time I was reading Jonathan Gabriel Valley. He is also an official restaurant scout Gold, and when I was older, my brother bought me my for Jonathan Gold at the L.A. -

COMFORT FOOD Family-Run Casa Moreno Serves Must-Try Mexican Dishes Steeped in Tradition and flavor

THREE SIXTY APRIL THE DISH COMFORT FOOD Family-run Casa Moreno serves must-try Mexican dishes steeped in tradition and flavor. %<(5,172%,1 t’s not easy to become a standout restaurant in Claremont Village, home to many incredible eateries, but Casa Moreno has been succeeding for I the last five years. Thanks to a festive atmosphere, great drinks and homestyle recipes that pay to tribute to the cuisine of Puebla, Mexico, Casa Moreno has secured its place on the must-try list. Dishes pull not only from pre-Hispanic and Spanish influences, but also from French and Lebanese styles. Mole Poblano is a perfect example of this fusion. “It is a wonderful dish prepared using as many as 30 ingre- dients and offers so many delicious flavors,” says Casa Moreno manager Susan Diaz. “It was said to be served as a treat for special guests or events like weddings. Our family recipe dates back as far as three generations and is a perfect blend of sweet and spicy.” One of Casa Moreno’s specialities is Mixiote. This dish is traditionally made with rabbit, but here it features beef marinated in an array of spices, then oven-cooked in corn husks. The presentation is beautiful as the meat Above, Owner Mercy is plated in its husk along with a sharp green salsa and Moreno outside the generous portions of refried beans and Mexican rice. Claremont location. The meat is tender and moist, and the salsa brings out Right, Fajita Trio features the subtle flavors of the marinade, especially when it’s a combination of steak, piled into some of Casa Moreno’s corn or flour tortillas. -

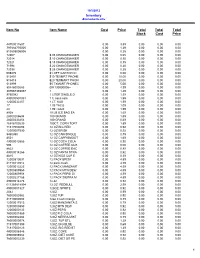

TX Convenient Database

10/5/2012 Inventory Alphabetically Item No Item Name Cost Price Total Total Total Stock Cost Price 44700011607 0.00 3.89 0.00 0.00 0.00 797884770005 0.00 1.29 0.00 0.00 0.00 813805005008 0.00 0.25 0.00 0.00 0.00 72007 $.05 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.05 0.00 0.00 0.00 72014 $.10 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.10 0.00 0.00 0.00 72021 $.15 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.15 0.00 0.00 0.00 71994 $.20 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.20 0.00 0.00 0.00 72038 $.25 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.25 0.00 0.00 0.00 609470 $1 OFF CARTON CI 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 513401 $10 TEXMRT PHONE 0.00 10.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 513418 $20 TEXMART PHON 0.00 20.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 513999 $5 TXMART PHONEC 0.00 5.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 90446000283 004130000006+ 0.00 4.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 307667393057 1 0.00 1.49 0.00 0.00 0.00 9750982 1 LITER SINGLE D 0.00 1.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 490000501031 1 lt. coca cola 0.00 1.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 12000032257 1 LT. KAS 0.00 1.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 17 1.09 TACO 0.00 1.09 0.00 0.00 0.00 24 1.99 TACO 0.00 1.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 8938 10 LB ICE BAG EA 0.00 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 28000206604 100 GRAND 0.00 1.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 28000333454 100 GRAND 0.00 0.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 16916100239 100CT.