Was the Taco Invented in Southern California?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPETIZERS Homemade SOUPS Desserts SPECIALTY TACOS

(575) 527-0817 1551 Amador Ave. Las Cruces, NM 88001 Sergio Castillo - Restaurant Manager Open Everyday 11:00am to 8:00pm www.sisenor.com APPETIZERS HOMEMADE SOUPS Bowl of soup M-F- $7.49 Upgrade to Large Soup - $1.99 Nachos .......................................................................... $9.59 Homemade corn tortilla chips topped with beans, taco meat, and Monday – Chicken and Rice Soup melted cheese. Lettuce, tomatoes and jalapeños upon request. Tuesday – Caldillo (Green Chile Beef Stew) Wednesday – Albondigas (Meatballs with Rice) Nachitos .....................................................................................$8.89 Thursday – Fideos (Vermicelli with Beef) Homemade corn tortilla chips topped with beans Friday – Cod Fish & Shrimp Soup w/ Vegetables & side of Rice and melted cheese. Saturday & Sunday Menudo - $7.79 Si Señor Wings ...........................................................$10.39 Caldo de Res - $8.09 (Vegetable Beef Soup & side of rice) Get these great wings slightly battered, perfectly cooked and Posole Fresh Daily - $7.69 served with a side of spicy BBQ sauce and ranch. Seasonal (Nov-Feb) Chile Cheese Fries ...............................................................$8.89 French fries smothered with cheese and your choice of red LITTLE ONES MENU or green chile. (12 years or younger only) ................................................................... Taco Plate ................................................................................... $6.39 House Sampler $10.59 One beef or chicken -

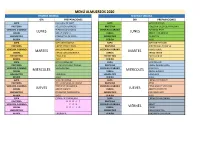

Lunes Martes Miercoles Jueves Menú Almuerzos 2020

MENÚ ALMUERZOS 2020 PRIMERA SEMANA SEGUNDA SEMANA DÍA PREPARACIONES DÍA PREPARACIONES SOPA CUCHUCO DE MAÌZ SOPA SOPA DE FIDEOS PROTEINA POLLO CON AJONJOLI PROTEINA POLLO EN SALSA DE MANZANA VERDURA O GRANO PEPINOS CON HUEVO VERDURA O GRANO TORTA DE PAPA CEREAL LUNES ARROZ BLANCO CEREAL LUNES ARROZ CON ARVEJA ENERGETICO CROQUETAS DE YUCA ENERGETICO TAJADITAS BEBIDA JUGO BEBIDA JUGO SOPA SOPA DE MAZORCA SOPA SOPA DE PATACON PROTEINA CARNE DESMECHADA PROTEINA ALBONDIGAS EN SALSA VERDURA O GRANO ARVEJA AMARILLA VERDURA O GRANO FRIJOL VERDE CEREAL MARTES ARROZ CON ZANAHORIA CEREAL MARTES ARROZ VERDE ENERGETICO ENSALADA ENERGETICO PAPA SALADA BEBIDA JUGO BEBIDA JUGO SOPA SOPA CAMPESINA SOPA SANCOCHITO PROTEINA ATÙN CON CHAMPIÑONES PROTEINA CARNE DESMECHADA VERDURA O GRANO MACARRONES VERDURA O GRANO MAZORCA CEREAL MIERCOLES CEREAL MIERCOLES ARROZ BLANCO ENERGETICO TAJADITAS ENERGETICO ENSALADA BEBIDA JUGO BEBIDA JUGO SOPA SOPA DE AVENA SOPA CREMA DE TOMATE PROTEINA POLLO EN SALSA DE QUESO PROTEINA ATUN VERDURA O GRANO TORTA DE ZANAHORIA VERDURA O GRANO ENSALADA DE VERDURA CEREAL JUEVES ARROZ BLANCO CEREAL JUEVES ARROZCON PEREJIL ENERGETICO CRIOLLITAS CHORRIADAS ENERGETICO PAPA ENCHUPE BEBIDA JUGO BEBIDA JUGO SOPA CREMA DE ZANAHORIA SOPA CREMA DE AHUYAMA PROTEINA A R R O Z PROTEINA VERDURA O GRANO C O N VERDURA O GRANO ARROZ CEREAL P O L L O CEREAL VIERNES CHINO ENERGETICO ENERGETICO PAPA FRANCESA BEBIDA LIMONADA BEBIDA LIMONADA CEREZADA TERCERA SEMANA CUARTA SEMANA DÍA PREPARACIONES DÍA PREPARACIONES SOPA SOPA DE ARROZ SOPA SOPA DE COLICERO -

APPETIZERS Homemade SOUPS SPECIALTY TACOS LITTLE ONES

(575) 527-0817 1551 Amador Ave., Las Cruces, NM 88001 Sergio Castillo - Restaurant Manager Open Everyday 11:00am to 8:00pm www.sisenor.com APPETIZERS HOMEMADE SOUPS Nachos ........................................................................$10.50 Bowl of soup M-F- $7.49 Upgrade to Large Soup - $1.99 handmade corn tortilla chips topped with refried beans, our signature queso, freshly grated Monterey Jack and cheddar Monday – Chicken and Rice Soup cheese, your choice of ground beef, shredded beef, or shredded Tuesday – Caldillo (Green Chile Beef Stew) chicken. Lettuce, tomatoes, and jalapeño upon request. Wednesday – Albondigas (Meatballs with Rice) Add carne asada or al pastor ..................................................$2.50 Thursday – Fideos (Vermicelli with Beef) Friday – Cod Fish & Shrimp Soup w/ Vegetables & side of Rice Si Señor Wings ................................................................ $11 Get these great wings slightly battered, perfectly cooked and Saturday & Sunday served with a side of spicy BBQ sauce and ranch. Menudo - $7.79 Caldo de Res - $8.09 (Vegetable Beef Soup & side of rice) Chile Cheese Fries ...............................................................$8.89 Posole Fresh Daily - $7.69 French fries with your choice of chile topped with melted, freshly Seasonal (Nov-Feb) grated Monterrey Jack and cheddar cheese. Asada or Al Pastor fries ................................................ $12 Crispy French fries topped with our signature queso, freshly LITTLE ONES MENU grated Monterey Jack and cheddar -

The Impact of the Mexican Revolution on Spanish in the United States∗

The impact of the Mexican Revolution on Spanish in the United States∗ John M. Lipski The Pennsylvania State University My charge today is to speak of the impact of the Mexican Revolution on Spanish in the United States. While I have spent more than forty years listening to, studying, and analyzing the Spanish language as used in the United States, I readily confess that the Mexican Revolution was not foremost in my thoughts for many of those years. My life has not been totally without revolutionary influence, however, since in my previous job, at the University of New Mexico, our department had revised its bylaws to reflect the principles of sufragio universal y no reelección. When I began to reflect on the full impact of the Mexican Revolution on U. S. Spanish, I immediately thought of the shelf-worn but not totally irrelevant joke about the student who prepared for his biology test by learning everything there was to know about frogs, one of the major topics of the chapter. When the day of the exam arrived, he discovered to his chagrin that the essay topic was about sharks. Deftly turning lemons into lemonade, he began his response: “Sharks are curious and important aquatic creatures bearing many resemblances to frogs, which have the following characteristics ...”, which he then proceeded to name. The joke doesn’t mention what grade he received for his effort. For the next few minutes I will attempt a similar maneuver, making abundant use of what I think I already know, hoping that you don’t notice what I know that I don’t know, and trying to get a passing grade at the end of the day. -

Torta Alla Crema Recipe

DOMENICA COOKS TORTA ALLA CREMA I came across this recipe while paging through a cookbook I bought in Italy on my last visit, in 2019: Le Stagioni della Pasticceria: 200 Ricette Dolci e Salate, by Italian pastry chef Martina Tribioli, with enticing photos by Barbara Torresan. It is, essentially a flan parisien—a buttery pastry shell filled to the brim with crema pasticcera (pastry cream) and baked. The flavor is delicate—vanilla and egg—just the sort of gentle flavors that evoke spring. If you’d like to punch it up a bit, you could serve it with a spring compote of rhubarb and strawberries. Or just scatter some berries on top and finish with a shower of confectioners’ sugar. Makes one 8-inch (20-cm) torta, to serve 8 INGREDIENTS For the base: 1 3/4 cups (225 g) unbleached all-purpose flour 1 tablespoon sugar 1/4 teaspoon fine salt 6 ounces (170 g; 3/4-cup; 1 1/2 sticks) unsalted butter, cut into cubes 1 large egg yolk 1/4 cup (60 ml) whole milk For the filling: 3 1/4 cups (750 ml) whole milk 1 to 2 vanilla beans 2 cups + 1 tablespoon + 1 teaspoon (220 g) sugar 4 large egg yolks plus 1 whole large egg 10 tablespoons (80 g) cornstarch Pinch of fine salt 1 cup (250 g) heavy whipping cream For serving: Fresh berries and confectioners’ sugar INSTRUCTIONS 1. Make the filling: Pour the milk into a saucepan and stir in the sugar. Split the vanilla beans and scrape out the seeds. -

Toward a Comprehensive Model For

Toward a Comprehensive Model for Nahuatl Language Research and Revitalization JUSTYNA OLKO,a JOHN SULLIVANa, b, c University of Warsaw;a Instituto de Docencia e Investigación Etnológica de Zacatecas;b Universidad Autonóma de Zacatecasc 1 Introduction Nahuatl, a Uto-Aztecan language, enjoyed great political and cultural importance in the pre-Hispanic and colonial world over a long stretch of time and has survived to the present day.1 With an estimated 1.376 million speakers currently inhabiting several regions of Mexico,2 it would not seem to be in danger of extinction, but in fact it is. Formerly the language of the Aztec empire and a lingua franca across Mesoamerica, after the Spanish conquest Nahuatl thrived in the new colonial contexts and was widely used for administrative and religious purposes across New Spain, including areas where other native languages prevailed. Although the colonial language policy and prolonged Hispanicization are often blamed today as the main cause of language shift and the gradual displacement of Nahuatl, legal steps reinforced its importance in Spanish Mesoamerica; these include the decision by the king Philip II in 1570 to make Nahuatl the linguistic medium for religious conversion and for the training of ecclesiastics working with the native people in different regions. Members of the nobility belonging to other ethnic groups, as well as numerous non-elite figures of different backgrounds, including Spaniards, and especially friars and priests, used spoken and written Nahuatl to facilitate communication in different aspects of colonial life and religious instruction (Yannanakis 2012:669-670; Nesvig 2012:739-758; Schwaller 2012:678-687). -

“Spanglish,” Using Spanish and English in the Same Conversation, Can Be Traced Back in Modern Times to the Middle of the 19Th Century

FAMILY, COMMUNITY, AND CULTURE 391 Logan, Irene, et al. Rebozos de la colección Robert Everts. Mexico City: Museo Franz Mayer, Artes de México, 1997. With English translation, pp. 49–57. López Palau, Luis G. Una región de tejedores: Santa María del Río. San Luis Potosí, Mexico: Cruz Roja Mexicana, 2002. The Rebozo Way. http://www.rebozoway.org/ Root, Regina A., ed. The Latin American Fashion Reader. New York: Berg, 2005. SI PANGL SH History and Origins The history of what people call “Spanglish,” using Spanish and English in the same conversation, can be traced back in modern times to the middle of the 19th century. In 1846 Mexico and the United States went to war. Mexico sur- rendered in 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. With its surrender, Mexico lost over half of its territory to the United States, what is now either all or parts of the states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Wyoming. The treaty estab- lished that Mexican citizens who remained in the new U.S. lands automatically became U.S. citizens, so a whole group of Spanish speakers was added to the U.S. population. Then, five years later the United States decided that it needed extra land to build a southern railway line that avoided the deep snow and the high passes of the northern route. This resulted in the Gadsden Purchase of 1853. This purchase consisted of portions of southern New Mexico and Arizona, and established the current U.S.-Mexico border. Once more, Mexican citizens who stayed in this area automatically became U.S. -

Botanas (Appetizers)

Salsa Macha GF Botanas (Appetizers) chile de arbol and garlic roasted to a nutty, spicy, crumbly salsa, served with queso Cochinita Pibil GF fresco, avocado and mini tortillas (spice up any entrée!) marinated pork in an achiote recipe, slowly roasted until tender, served wrapped in Shrimp Jalapeño Poppers three lightly seared mini tortillas, topped with seasoned marinated onions and mexican three tiger prawn shrimp stuffed with a hint of our house blend cheese, wrapped in crema 9 bacon, grilled jalapeño fried in beer batter, served with our chipotle cream sauce 15 Quesadilla Mini Empanaditas GF flour or corn masa tortillas with melted house blend oaxaca cheese, served with melted house blend oaxaca cheese with a jalapeño slice, or shrimp and chorizo topped guacamole, pico de gallo and sour cream 11 with crema and queso cotija, three empanaditas 9, six empanaditas 18 Add Shredded Chicken, Shredded Beef, Grilled Chicken, Carnitas, Chicken Tinga, Carne Asada, Sautéed Veggies or Shrimp 2 Guacamole GF avocado, tomatoes, onions, cilantro, jalapeños and fresh limes, topped with queso Quesadilla de Chipotle GF fresco and crispy tortillas 11 / 18 fresh corn masa with chipotle, filled with melted house blend oaxaca cheese, stuffed Add Shrimp or Crab Seared in Abuelo Spicy Sauce 2 with choice of sautéed veggies or black beans, served with pico de gallo, guacamole and sour cream 10 Queso Fundido GF Sopas y Ensaladas mexican blend of traditional oaxaca cheese melted in a cast iron pan, served with Sopa de Fideo choice of flour or corn mini tortillas -

Brunch Brunch Torta Quesadilla Tacos Soup

TAKING ORDERS: BRUNCH & LUNCH 10A-2:45P BRUNCH BRUNCH QUESADILLA Large Hand Made Corn Pollo Frito y Waffle 16 Breakfast Tacos: Tortilla With cheese. House Belgium waffle topped Bacon & Eggs 10 Choose Filling: with our Fried chicken. Side Pico Flour Tortillas, black beans, de Gallo & Syrup. +add Egg $2 Fried eggs (scrambled upon Just Cheese: 5 request), Bacon, Queso Fresco Beef & Eggs 16 Pollo | Carnitas | Veggies 8 Choice of Beef Barbacoa [OR] Breakfast Tacos: Beef Barbacoa | Steak 10 Premium thin cut steak, two Linguiça y Papa 10 Shrimp a la Diabla 10 fried eggs, Mexi-rice & black Flour Tortillas, black beans, beans, two corn tortillas, Linguiça sausage & potato ADD: Rice & Beans +3 guacamole & side salsa roja GF scrambled with eggs, Queso Fresco TACOS Chilaquiles 14 Organic Yellow Corn La Palma Corn Tortilla chips, Avocado Toast 8 Choose Roja [or] Verde, choice Tortillas with Choice of Made-to-order Avocado Mash, One Filling topped With of filling, two fried eggs, Marinated Tomato & Basil chimichurri, Queso Fresco. Pico de Gallo: GF Choose 1 filling: Carnitas, Pollo, [or] Veggies Each order has 2 Tacos Steak or shrimp +2 TORTA GF, *can be V sandwiches Pollo | Carnitas | Veggie 7 Verde Chilaquiles & Bacon & Steak Torta 14 Beef Barbacoa | Steak 8 Huevos a la Mexicana 12.50 Hickory smoked bacon, Lettuce, Avocado, Tomato, Steak in a Shrimp ala Diabla: 9 La Palma Corn Tortilla chips, salsa verde over Black Beans Brioche Bun ADD: Rice & Beans +3 topped with Huevos a la (gf, can be Vegan) Steak Torta 12 Mexicana (scrambled eggs with Steak, beans, cheese, lettuce, salsa roja), Sour Cream & Queso tomato, avocado, spicy mayo Fresco. -

Pressed Chicken Tortas with Romaine Salad, Queso Fresco & Avocado

Pressed Chicken Tortas with Romaine Salad, Queso Fresco & Avocado In Mexican cuisine, pressed tortas are meat-and-vegetable sandwiches similar to paninis. Using a press turns the rolls perfectly crispy, while bringing together the flavors in the layers of filling. Here, we’re simply using a heavy pot to press our pan-toasted tortas—filled with spiced chicken, avocado, tomato and queso fresco (a crumbly Mexican cheese). On the side, we’re serving a refreshing romaine salad with a bit of a kick to it, thanks to the chile powder and cumin in the sour cream-lime juice dressing. Ingredients 4 Boneless, Skin-On Chicken Thighs 4 Torta Rolls 2 Limes 2 Romaine Hearts 1 Avocado 1 Tomato 1 Red Onion 1 Bunch Cilantro Knick Knacks 4 Ounces Queso Fresco ⅓ Cup Pepitas ½ Cup Low-Fat Sour Cream 2 Teaspoons Chicken Torta Spice Blend Makes 4 Servings About 700 Calories Per Serving Prep Time: 15 min | Cook Time: 35 to 45 min For cooking tips & tablet view, visit blueapron.com/recipes/fp154 Recipe #154 Instructions For cooking tips & tablet view, visit blueapron.com/recipes/fp154 1 2 Prepare the ingredients: Cook the chicken: Wash and dry the fresh produce. Halve the rolls. Core, halve and Pat the chicken dry with paper towels; season on both sides with thinly slice the tomato. Crumble the queso fresco. Pick the cilantro salt, pepper and (reserving a pinch) as much of the spice blend leaves off the stems; discard the stems. Cut off and discard the as you’d like, depending on how spicy you’d like the dish to be. -

@Mezcalerodc 3714 14Th Street NW 202.803.2114

Antojitos 1. Ceviche de Atun $12 11. Mussels con Chorizo $11 Ahi Tuna/Avocado/Manzano Chorizo/Tecate Beer/Chipotle Chile/Toasted Peanuts Sauce/Bread 2. Ceviche de Pescado $11 12. Tacos de Canasta $7 Fish marinated in Lemon Juice with Basket of Tacos/Frijoles/Papas con Onions and fresh Habanero Chorizo/Chicharon/Guajillo Sauce/Queso 3. Cocktail de Camarones $12 Gulf Shrimp/Avocado/Spicy Cocktail 13. Queso Fundido $10 Sauce Spicy Chorizo/Oaxcaca Cheese/Chihuahua Cheese/Peppers 4. Ceviche De Mariscos $13 served with Corn or Flour Tortillas Shrimp/Crab/Oysters/Fish/Spicy Seafood Sauce 14. Mushroom Fundido $9 Wild Mushroom/Oaxcaca 5. Duo de Ceviche $16 Cheese/Chihuahua Cheese/Poblano Choose any 2: Ceviche de Peppers served with Corn or Flour Atún/Ceviche de Pescado/Cocktail de Tortillas Camarones/Ceviche de Mariscos 15. Guacamole $7 6. Mezcalero Salad $7 Avocado/Onion/Cilantro/Serrano Mixed Greens/Honey Peppers/Tomato/Lime and Chips Vinaigrette/Cheese/Cucumber/Onions/ Grated Orange Peel/Pumpkin Seeds 16. Oysters al Carbon $12 Chipotle Butter Sauce/Parmesan 7. Jalapeño Caesar Salad $8 Cheese/Bolillo Bread Romaine Lettuce/Croutons/Cheese/ Mezcalero Dressing/Sardines 17. Flautas $8 Choice of Crispy Chicken or Beef/Sour 8. Seafood Nachos $12 Cream/Queso Fresco/Lettuce/Pico de Crab/Shrimp/Spicy Gallo/Topped with Guacamole Cheese/Jalapeños/Sour Cream/Guacamole 18. Sopes Trio $7 Any choice of Protein/Beans/Romaine 9. Nachos $10 Lettuce/Sour Cream/Queso Fresco Chicken or Beef/Beans/Jalapeños/Sour Cream/Guacamole/Pico de Gallo 19. Molletes $8 Open-faced Sandwich with 10. Fried Oysters $12 Chorizo/Cheese/Pico de Gallo D.F. -

Food Truck Frenzy: an Analysis of the Gourmet Food Truck in Philadelphia

Food Truck Frenzy: An Analysis of the Gourmet Food Truck in Philadelphia Kevin Strand Sociology/Anthropology Department Swarthmore College May 11, 2015 Table of Contents I. Abstract.. .................................................................................................................. .3 II. Introduction ........................................................................................................... ..4 III. Literature Review .................................................................................................. 11 IV. Methodology .......................................................................................................... 2 2 V. Chapter 1-- Raising the Stakes with the New "Kids" on the Block ...................... 36 VI. Chapter 2-- From Food Trend to Valid Business Model.. .................................... 48 VII. Chapter 3-- Food Truck Fanatic? Or Food truck junkie? ........................................... 68 VIII. Conclusion: Looking Towards the Future .......................................................... 77 References ..................................................................................................................... 85 2 Abstract: For my senior thesis I am going to investigate the rampant rise in popularity of gourmet food trucks in the past six or seven years. When I first arrived at Swarthmore, our campus was visited by one upscale cupcake truck during the spring semester that had to endure a line of almost 150 people and ran out of ingredients within an