South–South Cooperation Beyond the Myths

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Issue 24 As

Policy & Practice A Development Education Review ISSN: 1748-135X Editor: Stephen McCloskey "The views expressed herein are those of individual authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of Irish Aid." © Centre for Global Education 2017 The Centre for Global Education is accepted as a charity by Inland Revenue under reference number XR73713 and is a Company Limited by Guarantee Number 25290 Contents Editorial Refugee Crisis or Humanitarian Crisis? Eoin Devereux 1 Focus Migration and Public Policy in a Fragmenting European Union Gerard McCann 6 Experiences, Barriers and Identity: The Development of a Workshop to Promote Understanding of and Empathy for the Migrant Experience Brighid Golden and Matt Cannon 26 The Role of Development Education in Highlighting the Realities and Challenging the Myths of Migration from the Global South to the Global North Simon Eten 47 Perspectives In Solving Refugee Issues Solidarity Must Come First Susan McMonagle 70 Development Education and the Psychosocial Dynamics of Migration Joram Tarusarira 88 Higher Education for Refugees: The Case of Syria Helen Avery and Salam Said 104 Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review i |P a g e News versus Newsfeed: The Impact of Social Media on Global Citizenship Education Emma Somers 126 The Role of Economic Citizenship Education in Advancing Global Education Jared Penner and Janita Sanderse 138 Viewpoint Brexit, Trump and Development Education Stephen McCloskey 159 Resource reviews Education, Learning and the Transformation of Development -

Emerging and Frontier Markets: the New Frontline Markets Professional Careers

GONCALVES GONCALVES THE BUSINESS Emerging and Frontier Economics Collection EXPERT PRESS Philip J. Romero and Jeffrey A. Edwards, Editors DIGITAL LIBRARIES Markets The New Frontline for Global Trade EBOOKS FOR • BUSINESS STUDENTS Marcus Goncalves • José Alves ALVES Curriculum-oriented, born- Goncalves and Alves’ work is a very interesting and digital books for advanced business students, written promising book for the development themes of emerging by academic thought markets. The style and quality of the material is worthy Emerging leaders who translate real- of respect, providing a clear analysis of the internation- world business experience al markets and global development of various economic into course readings and and commercial relations and trading routes. —Yurii reference materials for and Frontier students expecting to tackle Pozniak, International Management Consultant at management and leadership Ukroboronservis, Kiev, Ukraine. challenges during their Emerging and Frontier Markets: The New Frontline Markets professional careers. for Global Trade brings together a collection of insights POLICIES BUILT and a new outlook of the dynamics happening between AND FRONTIER MARKETS EMERGING BY LIBRARIANS The New Frontline for the emerging and the advanced markets. The book pro- • Unlimited simultaneous usage vides also an excellent, easy to read and straight-to-the Global Trade • Unrestricted downloading point economic and political description of the MENA, and printing BRICS, ASEAN, and CIVETS markets. A description that • Perpetual access for a should interest every person willing to invest, work or just one-time fee • No platform or acquire a deep understanding of the emerging markets maintenance fees economic and political conditions. —Réda Massoudi, BU • Free MARC records Director Management and Transformation Consult- • No license to execute ing, LMS Organization & Human Resources. -

Exploring Hugo Chávez's Use of Mimetisation to Build a Populist

Exploring Hugo Chávez’s use of mimetisation to build a populist hegemony in Venezuela Elena Block Rincones MSc, BA A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of Journalism and Communication Abstract “You too are Chávez”… (Hugo Chávez, 2012i) This thesis examines the political communication style developed by Hugo Chávez in his hegemonic construction of power and collective identity during the 14 years he governed Venezuela. This thesis is located in the field of political communication. A culturalist approach is used for the case, which prioritises issues of culture and power and acknowledges the role of human agency. Thus, it specifically focuses on the way the late President appears to have incrementally built an emotional, mimetic bond with his publics in a process that culminated in the mimetisation of the leader and his followers in a new collective, but top-down, identity called Chávez. This process expresses a hegemonic dynamic that involved the displacement of former dominant groups and rearrangement of power relations in Venezuela. The logic of mimetisation proposes an incremental logic of articulation whereby I tried to make sense of Chávez’s political communication style and success. It involves the study of the thread that joined together key elements in Chávez’s political communication style: hegemony and identity construction, political culture, populism, mediatisation, and communicational government. It is a style that appears to have exceeded classic populist forms of communication based on exerting an appeal to the people, towards more inclusive, participatory, symbolic-pragmatic forms of practising political communication that may have constituted the key to Chávez’s political success for 14 years. -

Functional Responses and Intraspecific

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ENTOMOLOGYENTOMOLOGY ISSN (online): 1802-8829 Eur. J. Entomol. 115: 232–241, 2018 http://www.eje.cz doi: 10.14411/eje.2018.022 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Functional responses and intraspecifi c competition in the ladybird Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) provided with Melanaphis sacchari (Homoptera: Aphididae) as prey PENGXIANG WU 1, 2, J ING ZHANG 1, 2, M UHAMMAD HASEEB 3, S HUO YAN 4, LAMBERT KANGA3 and R UNZHI ZHANG 1, * 1 Department of Entomology, State Key Laboratory of Integrated Management of Pest Insects and Rodents, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, #1-5 Beichen West Rd., Chaoyang, Beijing 100101, China; e-mails: [email protected] (Wu P.X.), [email protected] (Zhang J.), [email protected] (Zhang R.Z.) 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3 Center for Biological Control, Florida A&M University, Tallahassee, FL 32307-4100, USA; e-mails: [email protected] (Haseeb M.), [email protected] (Kanga L.) 4 National Agricultural Technology Extension and Service Center, Beijing 100125, China; e-mail: [email protected] (Yan S.) Key words. Coleoptera, Coccinellidae, Harmonia axyridis, Hemiptera, Aphididae, Melanaphis sacchari, functional response, intraspecifi c competition Abstract. Functional responses at each developmental stage of predators and intraspecifi c competition associated with direct interactions among them provide insights into developing biological control strategies for pests. The functional responses of Harmonia axyridis (Pallas) at each developmental stage of Melanaphis sacchari (Zehntner) and intraspecifi c competition among predators were evaluated under laboratory conditions. The results showed that all stages of H. axyridis displayed a type II func- tional response to M. -

Lucan's Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulf

Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Catherine Connors, Chair Alain Gowing Stephen Hinds Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2014 Laura Zientek University of Washington Abstract Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Catherine Connors Department of Classics This dissertation is an analysis of the role of landscape and the natural world in Lucan’s Bellum Civile. I investigate digressions and excurses on mountains, rivers, and certain myths associated aetiologically with the land, and demonstrate how Stoic physics and cosmology – in particular the concepts of cosmic (dis)order, collapse, and conflagration – play a role in the way Lucan writes about the landscape in the context of a civil war poem. Building on previous analyses of the Bellum Civile that provide background on its literary context (Ahl, 1976), on Lucan’s poetic technique (Masters, 1992), and on landscape in Roman literature (Spencer, 2010), I approach Lucan’s depiction of the natural world by focusing on the mutual effect of humanity and landscape on each other. Thus, hardships posed by the land against characters like Caesar and Cato, gloomy and threatening atmospheres, and dangerous or unusual weather phenomena all have places in my study. I also explore how Lucan’s landscapes engage with the tropes of the locus amoenus or horridus (Schiesaro, 2006) and elements of the sublime (Day, 2013). -

Documento Ingles

www.pwc.com/co Highlights of Colombia Economic analysis 2011 and 2012 forecast Wrap up 2011 Over the last few years, the global economy has been facing the consequences of the 2008 world financial crisis. The economic recovery tries to find its way at different paces. In the case of developed countries, the beginning of recovery has become a steep slope, whereas it seems to find room for maneuvering in the emerging countries. The United States and the Europe Union grew about 1.5% in 2011. Asian economies showed greater energy, with rates above 6.5%, except in the case of Japan. The real estate market in the United States is still at a standstill. Fears regarding public debt sustainability continued to be felt at the Euro Zone, as the fiscal tensions did in the countries of the European periphery, since it seems the confidence of agents has taken a long time to become reestablished. Colombia is part of the group of emerging countries that have managed to resist global tensions. Despite the contraction of overseas demand from developed countries and a greater restriction of foreign lending as a result of a greater risk aversion, the economy has managed to expand thanks to public and private actions. Regarding the economic policy, achievements such the enactment of the constitutional reform of royalties, the fiscal rule and the act on macroeconomic stability are worth highlighting. Low interest rates and inflation under control are signs of a stable economic environment. Colombian exports have not only diversified their target markets, but also profited the high prices of main basic goods such as oil and coal, among others. -

ROGE-2017-253 Prof. Bates

The Business and Management Review, Volume 9 Number 1 July 2017 An examination of market entry perspectives in Emerging Markets Marvin O. Bates Department of Marketing, College of Business Lewis University, USA Tom A. Buckles Department of Marketing & Entrepreneurship School of Business & Management Azusa Pacific University, Azusa, CA, USA Key Words Emerging Markets, Entry Strategies, BoP, Base of the Pyramid Abstract This article examines emerging markets from two major perspectives. First the financial growth models typically based on a country’s GDP growth; this financial growth perspective gave rise to seven major definitions of emerging markets: BRICs, CIVETS, MINT, etc. The second perspective is an economic levels perspective based on the World Economic Pyramid; this economic levels perspective resulted in three global categories – the Top, Middle and Base of the Pyramid (BoP) markets. A new market expansion and market entry strategic model is proposed for each of the three World Economic Pyramid levels: Inter-country expansion, Intra-country entry, adjacent market entry, and Opposite market entry approaches. Prahalad’s 4 A’s marketing strategy (Awareness, Affordability, Access and Availability) for the BoP market is discussed, and the requirement for an articulated marketing strategy for the “middle market” is identified. Six operational biases identified by BoP strategic theorists held by MNCs regarding BoP market approaches are identified and discussed. And finally, the BoP strategic theorists identified the need for a BoP marketing focus replacing the traditional 4P marketing approach (i.e., Product, Price, Place and Promotion) with a BoP 4A marketing approach (i.e., Awareness, Affordability, Access and Availability). This article summarizes these recently evolving perspectives and insights to provide a context for future market research in both emerging and BoP markets. -

Cuba and Alba's Grannacional Projects at the Intersection of Business

GLOBALIZATION AND THE SOCIALIST MULTINATIONAL: CUBA AND ALBA’S GRANNACIONAL PROJECTS AT THE INTERSECTION OF BUSINESS AND HUMAN RIGHTS Larry Catá Backer The Cuban Embargo has had a tremendous effect on forts. Most of these have used the United States, and the way in which Cuba is understood in the global le- its socio-political, economic, cultural and ideological gal order. The understanding has vitally affected the values as the great foil against which to battle. Over way in which Cuba is situated for study both within the course of the last half century, these efforts have and outside the Island. This “Embargo mentality” had mixed results. But they have had one singular has spawned an ideology of presumptive separation success—they have propelled Cuba to a level of in- that, colored either from the political “left” or fluence on the world stage far beyond what its size, “right,” presumes isolation as the equilibrium point military and economic power might have suggested. for any sort of Cuban engagement. Indeed, this “Em- Like the United States, Cuba has managed to use in- bargo mentality” has suggested that isolation and ternationalism, and especially strategically deployed lack of sustained engagement is the starting point for engagements in inter-governmental ventures, to le- any study of Cuba. Yet it is important to remember verage its influence and the strength of its attempted that the Embargo has affected only the character of interventions in each of these fields. (e.g., Huish & Cuba’s engagement rather than the possibility of that Kirk 2007). For this reason, if for no other, any great engagement as a sustained matter of policy and ac- effort by Cuba to influence behavior is worth careful tion. -

Synthetic Worlds Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry

Synthetic Worlds Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry Esther Leslie Synthetic Worlds Synthetic Worlds Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry Esther Leslie reaktion books Published by reaktion books ltd www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2005 Copyright © Esther Leslie 2005 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Colour printed by Creative Print and Design Group, Harmondsworth, Middlesex Printed and bound in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, Kings Lynn British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Leslie, Esther, 1964– Synthetic worlds: nature, art and the chemical industry 1.Art and science 2.Chemical industry - Social aspects 3.Nature (Aesthetics) I. Title 7-1'.05 isbn 1 86189 248 9 Contents introduction: Glints, Facets and Essence 7 one Substance and Philosophy, Coal and Poetry 25 two Eyelike Blots and Synthetic Colour 48 three Shimmer and Shine, Waste and Effort in the Exchange Economy 79 four Twinkle and Extra-terrestriality: A Utopian Interlude 95 five Class Struggle in Colour 118 six Nazi Rainbows 167 seven Abstraction and Extraction in the Third Reich 193 eight After Germany: Pollutants, Aura and Colours That Glow 218 conclusion: Nature’s Beautiful Corpse 248 References 254 Select Bibliography 270 Acknowledgements 274 Index 275 introduction Glints, Facets and Essence opposites and origins In Thomas Pynchon’s novel Gravity’s Rainbow a character remarks on an exploding missile whose approaching noise is heard only afterwards. The horror that the rocket induces is not just terror at its destructive power, but is a result of its reversal of the natural order of things. -

Civettictis Civetta – African Civet

Civettictis civetta – African Civet continued to include it in Viverra. Although several subspecies have been recorded, their validity remains questionable (Rosevear 1974; Coetzee 1977; Meester et al. 1986). Assessment Rationale The African Civet is listed as Least Concern as it is fairly common within the assessment region, inhabits a variety of habitats and vegetation types, and is present in numerous protected areas (including Kruger National Park). Camera-trapping studies suggest that there are healthy populations in the mountainous parts of Alastair Kilpin Limpopo’s Waterberg, Soutpansberg, and Alldays areas, as well as the Greater Lydenburg area of Mpumalanga. However, the species may be undergoing some localised Regional Red List status (2016) Least Concern declines due to trophy hunting and accidental persecution National Red List status (2004) Least Concern (for example, poisoning that targets larger carnivores). Furthermore, the increased use of predator-proof fencing Reasons for change No change in the growing game farming industry in South Africa can Global Red List status (2015) Least Concern limit movement of African Civets. The expansion of informal settlements has also increased snaring incidents, TOPS listing (NEMBA) (2007) None since it seems that civets are highly prone to snares due CITES listing (1978) Appendix III to their regular use of footpaths. Elsewhere in Africa, this (Botswana) species is an important component in the bushmeat trade. Although the bushmeat trade is not as severe within the Endemic No assessment -

The Third Wave of Development Players

>> POLICY BRIEF ISSN: 1989-2667 Nº 60 - NOVEMBER 2010 The third wave of development players Nils-Sjard Schulz The Millennium Development Goals (MDG) Summit in Sep - >> tember illustrated that traditional aid donors and the big emerg - ing economies are reviewing their respective roles as global development players, but failing to build actual commitments. HIGHLIGHTS Meanwhile, a third group of development providers has quietly entered • The evolving global the stage. The CIVETS group, which encompasses Colombia, Indone - governance of development sia, Vietnam, Egypt, Turkey and South Africa, is not only attractive to needs to go beyond DAC global investors; it also brings a new wave of development partnerships donors and the BRIC group. that go beyond the rich-poor logic and promote South-South knowl - edge exchange and peer-to-peer learning. • The CIVETS countries are not Although their financial resources are limited, this post-BRIC genera - only new economic poles, but tion has strong potential to help reshape the global governance of devel - also development providers opment with fresh ideas and innovative models, while also preserving investing in peer-to-peer the gains made in civilising donor-recipient relationships. Over the learning and horizontal next months, the scope and quality of development policy decisions partnerships. also depends on the role that the CIVETS countries will play at the G20, United Nations (UN) and Development Assistance Committee • These countries are bound to (DAC) levels. become strategic players at the G20, UN and IFI levels, while offering a third wave of BRINGING NEW PLAYERS ON BOARD, BUT HOW? partnerships to low- and The stakes for the global governance of development are getting middle-income countries. -

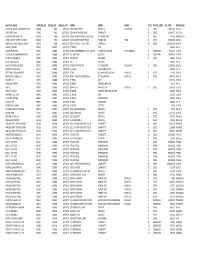

Supplier Name

SUPPLIER_NAME SUPPLIER_NO CHEQUE_NO CHEQUE_DATE ADDR1 ADDR2 ADDR3 STATE POSTAL_CODE INV_PAID INVOICE_NO OFFICE OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT SRF 04368 9683 6/3/2019 1201 MAIN STREET SUITE 910 COLUMBIA SC 29201 13,825.00 5-31-19 SOUTHEAST JACK C4690 9684 6/17/2019 7000 W WT HARRIS BLVD CHARLOTTE NC 28269 14,064.73 L6-17-19 GLOBAL AEROSPACE, INC. 09568 9686 6/17/2019 10895 GRANDVIEW DR, SUITE 150 OVERLAND PARK KS 66210 975.00 I00061547/01 YORK COUNTY CLERK OF COURT 00538 9687 6/26/2019 YORK COUNTY COURTHOUSE P O BOX 649 YORK SC 29745 35,000.00 6-26-19 JAMES, MCELROY & DIEHL TRUST 09567 9688 6/26/2019 525 N TRYON ST., SUITE 700 CHARLOTTE NC 28202 125,000.00 6-26-19 GIBSON, STEVEN 00957 230879 6/7/2019 EE #2679 OMB 209.96 6-2-19 UNUM PROVIDENT 01935 230880 6/7/2019 ATTN: VWB PREMIUM CLTN. & ACCT 1 FOUNTAIN SQUARE CHATTANOOGA TN 374021362 3,742.76 4-25-19 COMPORIUM COMMUNICATIONS 01951 230881 6/7/2019 P.O. BOX 1042 ROCK HILL SC 297317042 14,949.05 5-29-19 SC DEPT OF REVENUE 02000 230882 6/7/2019 TAX RETURN COLUMBIA SC 29214 486.00 5-31-19 SCOTT, MICHAEL W. 03826 230883 6/7/2019 CRH FIRE DEPT 200.00 6-5-19 BLUE CROSS BLUE SHIELD 04295 230884 6/7/2019 OF SOUTH CAROLINA P.O. BOX 6000 COLUMBIA SC 29260 11,959.40 5-21-19 BROWN, PAULA KNOX 06154 230885 6/7/2019 EE # 5036 SOLICITOR'S OFFICE 100.00 6-5-19 PRT TENNIS TOURNAMENT 06465 230886 6/7/2019 ATTN: 897 MAPLEWOOD LANE ROCK HILL SC 29730 112.00 5-29-19 NEXT LEVEL TENNIS, LLC 06525 230887 6/7/2019 ATTN: TEODORA DONCHEVA 872 DILLARD RD ROCK HILL SC 29730 7,897.60 N6-3-19 BROWN, LISA 07325 230888 6/7/2019 EE #5855 OMB 1,673.20 5-29-19 WINKLER, JEREMY 07922 230889 6/7/2019 EE #4207 GENERAL SERVICES 81.20 6-3-19 H.O.P.E.