Voting Rights in America Two Centuries of Struggle 3Rd Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

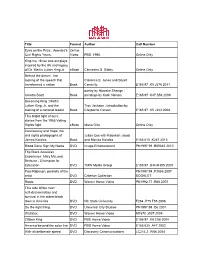

The Full Resource List

Title Format Author Call Number Eyes on the Prize : America's Online Civil Rights Years. Video PBS, 1990. Online Only King me : three one-act plays inspired by the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. eBook Clinnesha D. Sibley. Online Only Behind the dream : the making of the speech that Clarence B. Jones and Stuart transformed a nation Book Connelly. E185.97 .K5 J576 2011 poetry by Ntozake Shange ; Coretta Scott Book paintings by Kadir Nelson. E185.97 .K47 S53 2009 Becoming King : Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Troy Jackson ; introduction by making of a national leader Book Clayborne Carson. E185.97 .K5 J343 2008 This bright light of ours: stories from the 1965 Voting Rights fight eBook Maria Gitin. Online Only Controversy and Hope: the civil rights photographs of Julian Cox with Rebekah Jacob James Karales Book and Monica Karales E185.615 .K287 2013 Blood Done Sign My Name DVD Image Entertainment PN1997.99 .B59645 2010 The Black American Experience: Mary McLeod Bethune - Champion for Education DVD TMW Media Group E185.97 .B34 M385 2009 Paul Robeson: portraits of the PN1997.99 .P3885 2007 artist DVD Criterion Collection BOOKLET Roots DVD Warner Home Video PN1992.77 .R66 2007 This side of the river: self-determination and survival in the oldest black town in America DVD NC State University F264 .P75 T55 2006 Do the right thing DVD Universal City Studios PN1997.99 .D6 2001 Wattstax DVD Warner Home Video M1670 .W37 2004 Citizen King DVD PBS Home Video E185.97 .K5 C58 2004 America beyond the color line DVD PBS Home Video E185.625 .A47 2003 With all deliberate speed DVD Discovery Communications LC214.2 .W58 2004 Chisholm '72: Unbought and 20th Century Fox Home Unbossed DVD Entertainmen E840.8 .C48 C55 2004 Between the World and Me Book Ta-Nehisi Coates E185.615 .C6335 2015 The autobiography of Malcolm X Book Malcolm X E185.97 .L5 A3 2015 Dreams from my father : a story of race and inheritance Book Barack Obama E185.97 .O23 A3 2007 Up from slavery : an autobiography Book Booker T. -

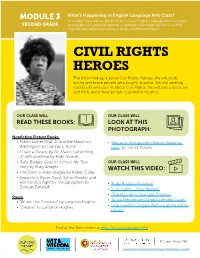

Tips for Families

GRADE 2 | MODULE 3 TIPS FOR FAMILIES WHAT IS MY GRADE 2 STUDENT LEARNING IN MODULE 3? Wit & Wisdom® is our English curriculum. It builds knowledge of key topics in history, science, and literature through the study of excellent texts. By reading and responding to stories and nonfiction texts, we will build knowledge of the following topics: Module 1: A Season of Change Module 2: The American West Module 3: Civil Rights Heroes Module 4: Good Eating In Module 3, we will study a number of strong and brave people who responded to the injustice they saw and experienced. By analyzing texts and art, students answer the question: How can people respond to injustice? OUR CLASS WILL READ THESE BOOKS Picture Books (Informational) ▪ Martin Luther King, Jr. and the March on Washington, Frances E. Ruffin; illustrations, Stephen Marchesi ▪ I Have a Dream, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; paintings, Kadir Nelson ▪ Ruby Bridges Goes to School: My True Story, Ruby Bridges ▪ The Story of Ruby Bridges, Robert Coles; illustrations, George Ford ▪ Separate is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation, Duncan Tonatiuh Poetry ▪ “Words Like Freedom,” Langston Hughes ▪ “Dreams,” Langston Hughes OUR CLASS WILL EXAMINE THIS PHOTOGRAPH ▪ Selma to Montgomery March, Alabama, 1965, James Karales OUR CLASS WILL READ THESE ARTICLES ▪ “Different Voices,” Anna Gratz Cockerille ▪ “When Peace Met Power,” Laura Helwegs OUR CLASS WILL WATCH THESE VIDEOS ▪ “Ruby Bridges Interview” ▪ “Civil Rights – Ruby Bridges” ▪ “The Man Who Changed America” For more resources, -

2008 Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Humanities

200808 ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES CHAIRMAN’S LETTER The President The White House Washington, D.C. 20500 Dear Mr. President: It is my privilege to present to you the 2008 annual report of the National Endowment for the Humanities. At the White House in February, I joined President Bush and Mrs. Bush to launch the largest and most ambitious nationwide initiative in NEH’s history: Picturing America, the newest element of our We the People program. Through Picturing America, NEH is distributing forty reproductions of American art masterpieces to schools and public libraries nationwide—where they will help stu- dents of all ages connect with the people, places, events, and ideas that have shaped our country. The selected works of art represent a broad range of American history and artistic achieve- ment, including Emanuel Leutze’s painting of Washington Crossing the Delaware; Mary Cassatt’s The Boating Party; the Chrysler Building in New York City; Norman Rockwell’s iconic Freedom of Speech; and James Karales’s stunning photo of the Selma-to-Montgomery March for Voting Rights in 1965. Accompanying the reproductions are a teacher’s guide and a dynamic website with ideas for using the images in the study of American history, literature, civics, and other subjects. During the first round of applications for Picturing America awards in the spring of 2008, nearly one-fifth of all the schools and public libraries in America applied for the program. In the fall, the first Picturing America sets arrived at more than 26,000 institutions nationwide, and we opened a second application window for Picturing America awards that will be distributed in 2009. -

Faulkner & Yoknapatawpha Conference 2013

the the newsletter of the Center for the study of southern Culture • spring 2013 the university of mississippi Faulkner & Yoknapatawpha Conference 2013 “Faulkner and the Black Literatures of the Americas” An impressive response to the call for papers for “Faulkner tablists will join the four invited keynote speakers and the and the Black Literatures of the Americas” has yielded 12 new featured panel of African American poets (both detailed in sessions featuring nearly three dozen speakers for the confer- earlier issues of the Register) to place Faulkner’s life and work ence, which will take place July 21–25, 2013, on the campus in conversation with a distinguished gallery of writers, art- of the University of Mississippi. These panelists and round- ists, and intellectual figures from African American and Afro- Caribbean culture, including Charles Waddell Chesnutt, W.E.B. Du Bois, Jean Toomer, painter William H. Johnson, Claude McKay, Delta bluesman Charley Patton, Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Wright, C.L.R. James, Ralph Ellison, Frantz Fanon, James Baldwin, Édouard Glissant, Marie Vieux- Chauvet, Toni Morrison, Randall Kenan, Suzan-Lori Parks, Edwidge Danticat, Edward P. Jones, Olympia Vernon, Natasha Trethewey, the editors and readers of Ebony magazine, and the writers and characters of the HBO series The Wire. In addi- tion, a roundtable scheduled for the opening afternoon of the conference will reflect on the legacies of the late Noel E. Polk as a teacher, critic, editor, collaborator, and longtime friend of the Faulkner & Yoknapatawpha Conference. Also selected through the call for papers was keynote speaker Tim A. Ryan, associate professor of English at Northern Illinois University and author of Calls and Responses: The American Novel of Slavery since “Gone with the Wind.” Professor Ryan’s keynote address is entitled “‘Go to Jail about This Spoonful’: Narcotic Determinism and Human Agency in ‘That Evening Sun’ and the Delta Blues.” This will be Professor Ryan’s first appearance at Faulkner & Yoknapatawpha. -

Lead Wit & Wisdom Resource Packet

Lead Wit & Wisdom® Resource Packet Professional Development Lead Wit & Wisdom Resource Packet WIT & WISDOM® Contents Wit & Wisdom K–8 Modules at a Glance .................................................................. 1 Kindergarten Module Synopses ............................................................................... 3 Grade 1 Module Synopses ...................................................................................... 7 Grade 2 Module Synopses ..................................................................................... 11 Grade 3 Module Synopses .....................................................................................15 Grade 4 Module Synopses .....................................................................................19 Grade 5 Module Synopses .................................................................................... 23 Grade 6 Module Synopses .................................................................................... 27 Grade 7 Module Synopses .....................................................................................31 Grade 8 Module Synopses .................................................................................... 35 Copyright © 2019 Great Minds® Lead Wit & Wisdom Resource Packet • K–8 Modules at a Glance WIT & WISDOM® Wit & Wisdom® K–8 Modules at a Glance Module 1 Module 2 Module 3 Module 4 The Five Senses Once Upon a Farm America, Then and Now The Continents How do our senses help us What makes a good story? How has life in America What makes -

CIVIL RIGHTS HEROES the Third Module Is About Civil Rights Heroes

MODULE 3 What’s Happening in English Language Arts Class? Your child’s class will use Wit & Wisdom as our English Language Arts curriculum. SECOND GRADE Your student will read and respond to excellent fiction and nonfiction writing. They will learn about key history, science, and literature topics. CIVIL RIGHTS HEROES The third module is about Civil Rights Heroes. We will study strong and brave people who fought injustice. We will carefully read books and poems about Civil Rights. We will also explore art and think about how people respond to injustice. OUR CLASS WILL OUR CLASS WILL READ THESE BOOKS: LOOK AT THIS PHOTOGRAPH: Nonfiction Picture Books • Martin Luther King, Jr. and the March on • “Selma to Montgomery March, Alabama, Washington by Frances E. Ruffin 1965” by James Karales • I Have a Dream, by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. with paintings by Kadir Nelson • Ruby Bridges Goes to School: My True OUR CLASS WILL Story by Ruby Bridges WATCH THIS VIDEO: • The Story of Ruby Bridges by Robert Coles • Separate is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation by • “Ruby Bridges Interview” Duncan Tonatiuh • “Civil Rights – Ruby Bridges” • “The Man Who Changed America” Poem • “Sylvia Mendez and Sandra Mendez Duran” • “Words Like Freedom” by Langston Hughes • “The Freedom Singers Perform at the White • “Dreams” by Langston Hughes House” Find all the links online at http://bit.ly/witwisdom2nd © Great Minds PBC www.baltimorecityschools.org/elementary-school OUR CLASS WILL OUR CLASS WILL LISTEN TO READ THESE THESE SONGS: -

MLK Day Resources Kids TEENS Separate Is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez & March, Volumes 1, 2, 3 by John Lewis Her Family’S Fight for Desegregation GRAPHIC BOOK LEW V

MLK Day Resources Kids TEENS Separate Is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez & March, Volumes 1, 2, 3 by John Lewis Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation GRaPhIC book lEW V. 1, V. 2, V.3 by Duncan Tonatiuh (j 379.263 ton) Turning 15 on the Road to Freedom: Voice of Freedom: Fannie Lou Hamer, My Story of the 1965 Selma Voting Spirit of the Civil Rights Movement Rights March by Lynda Lowery (j b ham) (Y 323.1196 LOW) A Good Kind of Trouble by Lisa Moore Ramée Twelve Days in May Freedom Ride 1961 (j Ram/CaUDIll) by Larry Dane Brimmer (j 323.092 bRI/CaUDIll) I am Martin Luther King, Jr. by Brad Meltzer (j b kIn) Stamped: Racism, Antiracism and You by Jason Reynolds (Y 305.8009 REY) I’m an Activist by Wil Mara (j 303.372 maR) The Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Seeds of Freedom: The Peaceful by Noah Berlatsky (Y 364.1524 ass) Integration of Huntsville, Alabama (j 323.1196 bas) M.L.K.: Journey of a King by Tonya Bolden (Y b kIn) Lillian’s Right to Vote: A Celebration of Dear Martin by Nic Stone (Y FIC STO) the Voting Rights Act of 1965 by Jonah Winter (PIC WIn) The March Against Fear: the Last Great Walk of the Civil Rights Movement and Let the Children March the Emergence of Black Power (PIC Cla/monaRCh) by Ann Bausum (Y 323.1196 baU) The Civil Rights Movement: An The Girl from the Tar Paper School: Barbara Rose Interactive History Adventure Johns and the Advent of the Civil Rights Movement (j 323.1196 aDa/YoU ChoosE books) by Teri Kanefield (Y 323.092 kan) The Civil Rights Movement by Eric Braun Freedom Walkers: the Story of the Montgomery Bus (j 323.1196 bRa) Boycott by Russell Freedman (Y 323.119 FRE) Child of the Civil Rights Movement All American Boys by Paula Young Shelton (j 323.1196 shE) by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely (Y FIC REY) The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas (Y FIC tho) Undefeated by Kwame Alexander and Kadir Nelson (j 811 alE/blUEstEm) Piecing Me Together by Renee Watson Lions of Little Rock by Kristin Levine (j lEV) (Y FIC WAT) Heroes of Black History (sound recording) How It Went Down by Kekla Magoon bk on CD j 973.049 Who (Y FIC maG) My Daddy, Dr. -

Eyesontheprize-Studyguide 201

A Blackside Publication A Study Guide Written by Facing History and Ourselves Copyright © 2006 Blackside, Inc. All rights reserved. Cover photos:(Signature march image) James Karales; (Front cover, left inset image) © Will Counts, Used with permission of Vivian Counts; (All other inset images) © Bettmann/Corbis Design by Planet Studio For permissions information, please see page 225 FOREWORD REP. JOHN LEWIS 5th Congressional District, Georgia The documentary series you are about to view is the story of how ordinary people with extraordinary vision redeemed “If you will protest courageously and democracy in America. It is a testament to nonviolent passive yet with dignity and …. love, when resistance and its power to reshape the destiny of a nation and the history books are written in future generations, the historians will the world. And it is the chronicle of a people who challenged have to pause and say, ‘There lies a one nation’s government to meet its moral obligation to great people, a black people, who humanity. injected new meaning and dignity We, the men, women, and children of the civil rights move- into the very veins of civilization.’ ment, truly believed that if we adhered to the discipline and This is our challenge and our philosophy of nonviolence, we could help transform America. responsibility.” We wanted to realize what I like to call, the Beloved Martin Luther King, Jr., Community, an all-inclusive, truly interracial democracy based Dec. 31, 1955 on simple justice, which respects the dignity and worth of every Montgomery, Alabama. human being. Central to our philosophical concept of the Beloved Community was the willingness to believe that every human being has the moral capacity to respect each other. -

K Leida Harlem Renaissance Artists DTI First Draft 11 05 13.Docx

Art in a Nation of Change – Visual Artists Influenced by the Harlem Renaissance Kristen L. Leida Introduction In the long history of the struggle for civil rights for African-Americans in the United States arose communities of artists during the early 20th century. In many areas shaped by ‘The Great Migration’ including Harlem, visual and performing artists flourished. My unit is comprised of artists who were inspired by and whose success grew as a result of the ‘Harlem Renaissance’. The lives of these visual artists were impacted by ‘The Great Migration’, their subject matter is derived from the experiences of African Americans and their artistic style was influenced by the viewpoint of the popularity of art in Harlem. As stated in Mike Venezia’s book, painter Jacob Lawrence chose the subjects he painted because “African-American history was hardly ever taught in schools when Jacob Lawrence was young. Jacob thought this was a serious problem. He knew that people who didn’t know about their history had no way of feeling proud of their past or of themselves.”1 Regardless of the school population’s characteristics, I believe it is important to incorporate art created from all races, genders and religions in the art program. As an Art teacher in a multi-cultural school, it’s critical for me to teach artists that reflect the diverse population to give the students a sense of origin, understanding and self-importance. The 2013-14 school year is my 9th in the Colonial School District and my 5th at Harry O. Eisenberg Elementary School (‘Eisenberg’). -

Ford Foundation Annual Report 2006

MISSION STATEMENT FORD FOUNDATION The Ford Foundation is a resource for innovative people and institutions worldwide. Our goals are to: STRENGTHEN DEMOCRATIC VALUES ReDUCE POVERTY AND INJUSTICE PROMOTE INTERNATIONAL COOpeRATION AND 1936 1951 1960 1964 1968 1976 1979 1988 1992 1998 2000 2004 2005 2006 ADVANCE HUMAN ACHIEVEMENT This has been our purpose for more than half a century. FORD FOUNDATION A fundamental challenge facing every society is to create political, economic and social systems that promote peace, human welfare and the sustainability of the environment on which life depends. We believe that the best way to meet Delivering this challenge is to encourage initiatives by those living and working closest to where problems are located; to promote collaboration among the nonprofit, government and business sectors; and to ensure participation by men and women on a promise with a diversity of from diverse communities and at all levels of society. In our experience, such activities help build common understanding, enhance excellence, enable people ANNUA to improve their lives and reinforce their commitment to society. to advance approaches and The Ford Foundation is one source of support for these activities. We work mainly by making grants or loans that build knowledge and strengthen organizations L R and networks. Since our financial resources are modest in comparison to societal EP needs, we focus on a limited number of problem areas and program strategies ORT human welfare continuity of purpose within our broad goals. 2006 Founded in 1936, the foundation operated as a local philanthropy in the state of Michigan until 1950, when it expanded to become a national and international foundation. -

19-B James Karales, Selma-To-Montgomery March For

JAMES KARALES [1930–2002] 19 b Selma-to-Montgomery March for Voting Rights in 1965,1965 On August 7, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed the invisible hands beneath a heavy, black thundercloud that Voting Rights Act, one of the most important pieces of legisla- appears ready to break. tion in America since the era of Reconstruction. It signaled the In the week before Karales took this iconic picture, two unsuc- victory of a battle that was fought five months earlier in Dallas cessful attempts to march on the capital had already been County, Alabama. On March 25, twenty-five thousand partici- made. On Sunday, March 5, the first activists, recorded by tele- pants — the largest civil rights gathering the South had yet vision cameras and still photographers, crossed the Edmund seen — converged on the state capital of Montgomery, con- Pettus Bridge out of Selma. Horrified viewers watched as cluding a four-day march for voting rights that began in Selma, unarmed marchers, including women and children, were fifty-four miles away. assaulted by Alabama state troopers using tear gas, clubs, James Karales, a photographer for the popular biweekly maga- and whips. The group turned back battered but undefeated. zine Look, was sent to illustrate an article covering the march. “Bloody Sunday,” as it became known, only strengthened the Titled “Turning Point for the Church,” the piece focused on movement and increased public support. Ordinary citizens, as the involvement of the clergy in the civil rights movement — well as priests, ministers, nuns, and rabbis who had been called specifically, the events in Selma that followed the murder of a to Selma by Dr. -

A Blackside Publication a Study Guide Written by Facing History and Ourselves Copyright © 2006 Blackside, Inc

A Blackside Publication A Study Guide Written by Facing History and Ourselves Copyright © 2006 Blackside, Inc. All rights reserved. Cover photos:(Signature march image) James Karales; (Front cover, left inset image) © Will Counts, Used with permission of Vivian Counts; (All other inset images) © Bettmann/Corbis Design by Planet Studio For permissions information, please see page 225 FOREWORD REP. JOHN LEWIS 5th Congressional District, Georgia The documentary series you are about to view is the story of how ordinary people with extraordinary vision redeemed “If you will protest courageously and democracy in America. It is a testament to nonviolent passive yet with dignity and …. love, when resistance and its power to reshape the destiny of a nation and the history books are written in future generations, the historians will the world. And it is the chronicle of a people who challenged have to pause and say, ‘There lies a one nation’s government to meet its moral obligation to great people, a black people, who humanity. injected new meaning and dignity We, the men, women, and children of the civil rights move- into the very veins of civilization.’ ment, truly believed that if we adhered to the discipline and This is our challenge and our philosophy of nonviolence, we could help transform America. responsibility.” We wanted to realize what I like to call, the Beloved Martin Luther King, Jr., Community, an all-inclusive, truly interracial democracy based Dec. 31, 1955 on simple justice, which respects the dignity and worth of every Montgomery, Alabama. human being. Central to our philosophical concept of the Beloved Community was the willingness to believe that every human being has the moral capacity to respect each other.