K Leida Harlem Renaissance Artists DTI First Draft 11 05 13.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

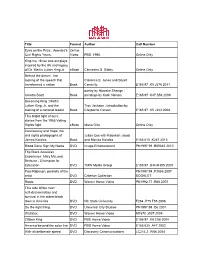

The Full Resource List

Title Format Author Call Number Eyes on the Prize : America's Online Civil Rights Years. Video PBS, 1990. Online Only King me : three one-act plays inspired by the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. eBook Clinnesha D. Sibley. Online Only Behind the dream : the making of the speech that Clarence B. Jones and Stuart transformed a nation Book Connelly. E185.97 .K5 J576 2011 poetry by Ntozake Shange ; Coretta Scott Book paintings by Kadir Nelson. E185.97 .K47 S53 2009 Becoming King : Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Troy Jackson ; introduction by making of a national leader Book Clayborne Carson. E185.97 .K5 J343 2008 This bright light of ours: stories from the 1965 Voting Rights fight eBook Maria Gitin. Online Only Controversy and Hope: the civil rights photographs of Julian Cox with Rebekah Jacob James Karales Book and Monica Karales E185.615 .K287 2013 Blood Done Sign My Name DVD Image Entertainment PN1997.99 .B59645 2010 The Black American Experience: Mary McLeod Bethune - Champion for Education DVD TMW Media Group E185.97 .B34 M385 2009 Paul Robeson: portraits of the PN1997.99 .P3885 2007 artist DVD Criterion Collection BOOKLET Roots DVD Warner Home Video PN1992.77 .R66 2007 This side of the river: self-determination and survival in the oldest black town in America DVD NC State University F264 .P75 T55 2006 Do the right thing DVD Universal City Studios PN1997.99 .D6 2001 Wattstax DVD Warner Home Video M1670 .W37 2004 Citizen King DVD PBS Home Video E185.97 .K5 C58 2004 America beyond the color line DVD PBS Home Video E185.625 .A47 2003 With all deliberate speed DVD Discovery Communications LC214.2 .W58 2004 Chisholm '72: Unbought and 20th Century Fox Home Unbossed DVD Entertainmen E840.8 .C48 C55 2004 Between the World and Me Book Ta-Nehisi Coates E185.615 .C6335 2015 The autobiography of Malcolm X Book Malcolm X E185.97 .L5 A3 2015 Dreams from my father : a story of race and inheritance Book Barack Obama E185.97 .O23 A3 2007 Up from slavery : an autobiography Book Booker T. -

Tips for Families

GRADE 2 | MODULE 3 TIPS FOR FAMILIES WHAT IS MY GRADE 2 STUDENT LEARNING IN MODULE 3? Wit & Wisdom® is our English curriculum. It builds knowledge of key topics in history, science, and literature through the study of excellent texts. By reading and responding to stories and nonfiction texts, we will build knowledge of the following topics: Module 1: A Season of Change Module 2: The American West Module 3: Civil Rights Heroes Module 4: Good Eating In Module 3, we will study a number of strong and brave people who responded to the injustice they saw and experienced. By analyzing texts and art, students answer the question: How can people respond to injustice? OUR CLASS WILL READ THESE BOOKS Picture Books (Informational) ▪ Martin Luther King, Jr. and the March on Washington, Frances E. Ruffin; illustrations, Stephen Marchesi ▪ I Have a Dream, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; paintings, Kadir Nelson ▪ Ruby Bridges Goes to School: My True Story, Ruby Bridges ▪ The Story of Ruby Bridges, Robert Coles; illustrations, George Ford ▪ Separate is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation, Duncan Tonatiuh Poetry ▪ “Words Like Freedom,” Langston Hughes ▪ “Dreams,” Langston Hughes OUR CLASS WILL EXAMINE THIS PHOTOGRAPH ▪ Selma to Montgomery March, Alabama, 1965, James Karales OUR CLASS WILL READ THESE ARTICLES ▪ “Different Voices,” Anna Gratz Cockerille ▪ “When Peace Met Power,” Laura Helwegs OUR CLASS WILL WATCH THESE VIDEOS ▪ “Ruby Bridges Interview” ▪ “Civil Rights – Ruby Bridges” ▪ “The Man Who Changed America” For more resources, -

2008 Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Humanities

200808 ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES CHAIRMAN’S LETTER The President The White House Washington, D.C. 20500 Dear Mr. President: It is my privilege to present to you the 2008 annual report of the National Endowment for the Humanities. At the White House in February, I joined President Bush and Mrs. Bush to launch the largest and most ambitious nationwide initiative in NEH’s history: Picturing America, the newest element of our We the People program. Through Picturing America, NEH is distributing forty reproductions of American art masterpieces to schools and public libraries nationwide—where they will help stu- dents of all ages connect with the people, places, events, and ideas that have shaped our country. The selected works of art represent a broad range of American history and artistic achieve- ment, including Emanuel Leutze’s painting of Washington Crossing the Delaware; Mary Cassatt’s The Boating Party; the Chrysler Building in New York City; Norman Rockwell’s iconic Freedom of Speech; and James Karales’s stunning photo of the Selma-to-Montgomery March for Voting Rights in 1965. Accompanying the reproductions are a teacher’s guide and a dynamic website with ideas for using the images in the study of American history, literature, civics, and other subjects. During the first round of applications for Picturing America awards in the spring of 2008, nearly one-fifth of all the schools and public libraries in America applied for the program. In the fall, the first Picturing America sets arrived at more than 26,000 institutions nationwide, and we opened a second application window for Picturing America awards that will be distributed in 2009. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI fihns the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in ^ e w rite r free, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Infonnation Company 300 North Zed) Road, Ann Aibor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 THE INFUSION OF AFRICAN AMERICAN ART FROM EIGHTEEN-EIGHTY TO THE EARLY NINETEEN-NINETIES FOR MIDDLE AND HIGH SCHOOL ART EDUCATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ronald Wayne Claxton, B.S., M.A.E. -

Faulkner & Yoknapatawpha Conference 2013

the the newsletter of the Center for the study of southern Culture • spring 2013 the university of mississippi Faulkner & Yoknapatawpha Conference 2013 “Faulkner and the Black Literatures of the Americas” An impressive response to the call for papers for “Faulkner tablists will join the four invited keynote speakers and the and the Black Literatures of the Americas” has yielded 12 new featured panel of African American poets (both detailed in sessions featuring nearly three dozen speakers for the confer- earlier issues of the Register) to place Faulkner’s life and work ence, which will take place July 21–25, 2013, on the campus in conversation with a distinguished gallery of writers, art- of the University of Mississippi. These panelists and round- ists, and intellectual figures from African American and Afro- Caribbean culture, including Charles Waddell Chesnutt, W.E.B. Du Bois, Jean Toomer, painter William H. Johnson, Claude McKay, Delta bluesman Charley Patton, Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Wright, C.L.R. James, Ralph Ellison, Frantz Fanon, James Baldwin, Édouard Glissant, Marie Vieux- Chauvet, Toni Morrison, Randall Kenan, Suzan-Lori Parks, Edwidge Danticat, Edward P. Jones, Olympia Vernon, Natasha Trethewey, the editors and readers of Ebony magazine, and the writers and characters of the HBO series The Wire. In addi- tion, a roundtable scheduled for the opening afternoon of the conference will reflect on the legacies of the late Noel E. Polk as a teacher, critic, editor, collaborator, and longtime friend of the Faulkner & Yoknapatawpha Conference. Also selected through the call for papers was keynote speaker Tim A. Ryan, associate professor of English at Northern Illinois University and author of Calls and Responses: The American Novel of Slavery since “Gone with the Wind.” Professor Ryan’s keynote address is entitled “‘Go to Jail about This Spoonful’: Narcotic Determinism and Human Agency in ‘That Evening Sun’ and the Delta Blues.” This will be Professor Ryan’s first appearance at Faulkner & Yoknapatawpha. -

News Release the Metropolitan Museum of Art

news release The Metropolitan Museum of Art For Release: Contact: Immediate Harold Holzer Norman Keyes, Jr. SCHEDULE OF EXHIBITIONS - JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1994 EDITORS PLEASE NOTE: Information provided below is subject to change. To confirm scheduling and dates, call the Communications Department (212) 570-3951. For Upcoming Exhibitions, see page 3; Continuing Exhibitions, page 8; New and Upcoming Permanent Installations, page 10; Traveling Exhibitions, page 12; Visitor Information, pages 13, 14. EDITORS PLEASE NOTE: On April 13, the Metropolitan will open for the first time sixteen permanent galleries embracing the arts of India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Tibet, Indonesia, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Burma, and Malaysia. The new Florence and Herbert Irving Galleries for the Arts of South and Southeast Asia will include some 1300 works, most of which have not been publicly displayed at the Museum before. Dates of several special exhibitions have been extended, including Church's Great Picture: The Heart of the Andes (through January 30); A Decade of Collecting: Friends of Asian Art Gifts, 1984- 1993 (through January 30); and Tang Family Gifts of Chinese Painting (indefinite close). Museum visitors may now for the first time enter the vestibule or pronaos of the Temple of Dendur in The Sackler Wing, and peer into the antechamber and sanctuary further within this Nubian temple, which is one of the most popular attractions at the Metropolitan. Three steps have been installed on the south side to facilitate closer study of the monument and its wall reliefs; a ramp has been added on the eastern end for wheelchair access. (Press Viewing: Wednesday, January 19, 10:00 a.m.-noon). -

Lead Wit & Wisdom Resource Packet

Lead Wit & Wisdom® Resource Packet Professional Development Lead Wit & Wisdom Resource Packet WIT & WISDOM® Contents Wit & Wisdom K–8 Modules at a Glance .................................................................. 1 Kindergarten Module Synopses ............................................................................... 3 Grade 1 Module Synopses ...................................................................................... 7 Grade 2 Module Synopses ..................................................................................... 11 Grade 3 Module Synopses .....................................................................................15 Grade 4 Module Synopses .....................................................................................19 Grade 5 Module Synopses .................................................................................... 23 Grade 6 Module Synopses .................................................................................... 27 Grade 7 Module Synopses .....................................................................................31 Grade 8 Module Synopses .................................................................................... 35 Copyright © 2019 Great Minds® Lead Wit & Wisdom Resource Packet • K–8 Modules at a Glance WIT & WISDOM® Wit & Wisdom® K–8 Modules at a Glance Module 1 Module 2 Module 3 Module 4 The Five Senses Once Upon a Farm America, Then and Now The Continents How do our senses help us What makes a good story? How has life in America What makes -

(Los Angeles—October 11, 2018) the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) Is Pleased to Host the West Coast Presentation Of

Image captions on page 5 (Los Angeles—October 11, 2018) The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) is pleased to host the West Coast presentation of Outliers and American Vanguard Art, the first major exhibition to explore key moments in American art history when avant-garde artists and outliers intersected, and how their exchanges ushered in new paradigms based on inclusion, integration, and assimilation. Featuring over 250 works in a range of media, the show will present works by more than 80 self-taught and trained artists such as Henry Darger, Sam Doyle, William Edmondson, Lonnie Holley, Greer Lankton, Sister Gertrude Morgan, Matt Mullican, Horace Pippin, Martín Ramírez, Betye Saar, Judith Scott, Charles Sheeler, Cindy Sherman, Bill Traylor, and Kara Walker. Outliers and American Vanguard Art is curated by Lynne Cooke and organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, where it was on view January 28–May 13, 2018. The show then traveled to the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, where it was on view June 24–September 30, 2018. The presentation at LACMA is coordinated by Rita Gonzalez, curator and acting department head of Contemporary Art. “LACMA has a longstanding relationship with the content presented in Outliers,” said Michael Govan, LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director. “Parallel Visions: Modern Artists and Outsider Art, presented at LACMA in 1992, signaled the breakdown of a model based on center and periphery relations; and the museum has been bringing vernacular photography, folk art, and art by the self-taught into the collection. We are now pleased to host Outliers and American Vanguard Art, further exploring often overlooked histories and artists.” “Outliers offers a profoundly different way of assessing how modernism unfolded both in official enclaves, like the Museum of Modern Art and Whitney Museum of American Art, but and in peer-to-peer, artist-driven networks,” Rita Gonzalez added. -

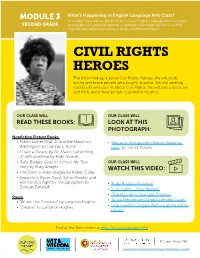

CIVIL RIGHTS HEROES the Third Module Is About Civil Rights Heroes

MODULE 3 What’s Happening in English Language Arts Class? Your child’s class will use Wit & Wisdom as our English Language Arts curriculum. SECOND GRADE Your student will read and respond to excellent fiction and nonfiction writing. They will learn about key history, science, and literature topics. CIVIL RIGHTS HEROES The third module is about Civil Rights Heroes. We will study strong and brave people who fought injustice. We will carefully read books and poems about Civil Rights. We will also explore art and think about how people respond to injustice. OUR CLASS WILL OUR CLASS WILL READ THESE BOOKS: LOOK AT THIS PHOTOGRAPH: Nonfiction Picture Books • Martin Luther King, Jr. and the March on • “Selma to Montgomery March, Alabama, Washington by Frances E. Ruffin 1965” by James Karales • I Have a Dream, by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. with paintings by Kadir Nelson • Ruby Bridges Goes to School: My True OUR CLASS WILL Story by Ruby Bridges WATCH THIS VIDEO: • The Story of Ruby Bridges by Robert Coles • Separate is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation by • “Ruby Bridges Interview” Duncan Tonatiuh • “Civil Rights – Ruby Bridges” • “The Man Who Changed America” Poem • “Sylvia Mendez and Sandra Mendez Duran” • “Words Like Freedom” by Langston Hughes • “The Freedom Singers Perform at the White • “Dreams” by Langston Hughes House” Find all the links online at http://bit.ly/witwisdom2nd © Great Minds PBC www.baltimorecityschools.org/elementary-school OUR CLASS WILL OUR CLASS WILL LISTEN TO READ THESE THESE SONGS: -

MLK Day Resources Kids TEENS Separate Is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez & March, Volumes 1, 2, 3 by John Lewis Her Family’S Fight for Desegregation GRAPHIC BOOK LEW V

MLK Day Resources Kids TEENS Separate Is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez & March, Volumes 1, 2, 3 by John Lewis Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation GRaPhIC book lEW V. 1, V. 2, V.3 by Duncan Tonatiuh (j 379.263 ton) Turning 15 on the Road to Freedom: Voice of Freedom: Fannie Lou Hamer, My Story of the 1965 Selma Voting Spirit of the Civil Rights Movement Rights March by Lynda Lowery (j b ham) (Y 323.1196 LOW) A Good Kind of Trouble by Lisa Moore Ramée Twelve Days in May Freedom Ride 1961 (j Ram/CaUDIll) by Larry Dane Brimmer (j 323.092 bRI/CaUDIll) I am Martin Luther King, Jr. by Brad Meltzer (j b kIn) Stamped: Racism, Antiracism and You by Jason Reynolds (Y 305.8009 REY) I’m an Activist by Wil Mara (j 303.372 maR) The Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Seeds of Freedom: The Peaceful by Noah Berlatsky (Y 364.1524 ass) Integration of Huntsville, Alabama (j 323.1196 bas) M.L.K.: Journey of a King by Tonya Bolden (Y b kIn) Lillian’s Right to Vote: A Celebration of Dear Martin by Nic Stone (Y FIC STO) the Voting Rights Act of 1965 by Jonah Winter (PIC WIn) The March Against Fear: the Last Great Walk of the Civil Rights Movement and Let the Children March the Emergence of Black Power (PIC Cla/monaRCh) by Ann Bausum (Y 323.1196 baU) The Civil Rights Movement: An The Girl from the Tar Paper School: Barbara Rose Interactive History Adventure Johns and the Advent of the Civil Rights Movement (j 323.1196 aDa/YoU ChoosE books) by Teri Kanefield (Y 323.092 kan) The Civil Rights Movement by Eric Braun Freedom Walkers: the Story of the Montgomery Bus (j 323.1196 bRa) Boycott by Russell Freedman (Y 323.119 FRE) Child of the Civil Rights Movement All American Boys by Paula Young Shelton (j 323.1196 shE) by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely (Y FIC REY) The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas (Y FIC tho) Undefeated by Kwame Alexander and Kadir Nelson (j 811 alE/blUEstEm) Piecing Me Together by Renee Watson Lions of Little Rock by Kristin Levine (j lEV) (Y FIC WAT) Heroes of Black History (sound recording) How It Went Down by Kekla Magoon bk on CD j 973.049 Who (Y FIC maG) My Daddy, Dr. -

Eyesontheprize-Studyguide 201

A Blackside Publication A Study Guide Written by Facing History and Ourselves Copyright © 2006 Blackside, Inc. All rights reserved. Cover photos:(Signature march image) James Karales; (Front cover, left inset image) © Will Counts, Used with permission of Vivian Counts; (All other inset images) © Bettmann/Corbis Design by Planet Studio For permissions information, please see page 225 FOREWORD REP. JOHN LEWIS 5th Congressional District, Georgia The documentary series you are about to view is the story of how ordinary people with extraordinary vision redeemed “If you will protest courageously and democracy in America. It is a testament to nonviolent passive yet with dignity and …. love, when resistance and its power to reshape the destiny of a nation and the history books are written in future generations, the historians will the world. And it is the chronicle of a people who challenged have to pause and say, ‘There lies a one nation’s government to meet its moral obligation to great people, a black people, who humanity. injected new meaning and dignity We, the men, women, and children of the civil rights move- into the very veins of civilization.’ ment, truly believed that if we adhered to the discipline and This is our challenge and our philosophy of nonviolence, we could help transform America. responsibility.” We wanted to realize what I like to call, the Beloved Martin Luther King, Jr., Community, an all-inclusive, truly interracial democracy based Dec. 31, 1955 on simple justice, which respects the dignity and worth of every Montgomery, Alabama. human being. Central to our philosophical concept of the Beloved Community was the willingness to believe that every human being has the moral capacity to respect each other.