Eyesontheprize-Studyguide 201

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Full Resource List

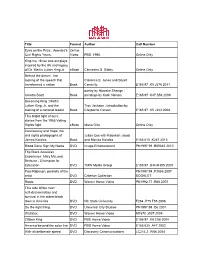

Title Format Author Call Number Eyes on the Prize : America's Online Civil Rights Years. Video PBS, 1990. Online Only King me : three one-act plays inspired by the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. eBook Clinnesha D. Sibley. Online Only Behind the dream : the making of the speech that Clarence B. Jones and Stuart transformed a nation Book Connelly. E185.97 .K5 J576 2011 poetry by Ntozake Shange ; Coretta Scott Book paintings by Kadir Nelson. E185.97 .K47 S53 2009 Becoming King : Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Troy Jackson ; introduction by making of a national leader Book Clayborne Carson. E185.97 .K5 J343 2008 This bright light of ours: stories from the 1965 Voting Rights fight eBook Maria Gitin. Online Only Controversy and Hope: the civil rights photographs of Julian Cox with Rebekah Jacob James Karales Book and Monica Karales E185.615 .K287 2013 Blood Done Sign My Name DVD Image Entertainment PN1997.99 .B59645 2010 The Black American Experience: Mary McLeod Bethune - Champion for Education DVD TMW Media Group E185.97 .B34 M385 2009 Paul Robeson: portraits of the PN1997.99 .P3885 2007 artist DVD Criterion Collection BOOKLET Roots DVD Warner Home Video PN1992.77 .R66 2007 This side of the river: self-determination and survival in the oldest black town in America DVD NC State University F264 .P75 T55 2006 Do the right thing DVD Universal City Studios PN1997.99 .D6 2001 Wattstax DVD Warner Home Video M1670 .W37 2004 Citizen King DVD PBS Home Video E185.97 .K5 C58 2004 America beyond the color line DVD PBS Home Video E185.625 .A47 2003 With all deliberate speed DVD Discovery Communications LC214.2 .W58 2004 Chisholm '72: Unbought and 20th Century Fox Home Unbossed DVD Entertainmen E840.8 .C48 C55 2004 Between the World and Me Book Ta-Nehisi Coates E185.615 .C6335 2015 The autobiography of Malcolm X Book Malcolm X E185.97 .L5 A3 2015 Dreams from my father : a story of race and inheritance Book Barack Obama E185.97 .O23 A3 2007 Up from slavery : an autobiography Book Booker T. -

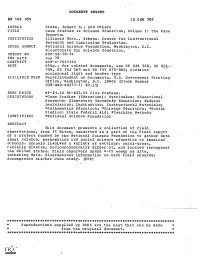

CONTRACT Case Studies in Science Education, Volume I: the Case 658P.; for Related Documents, See SE 026 360, SE 0261 Occasional

DOCUMENT RESUME E6 166 058 SE 026 707 AUTHOR Stake, Robert E.; And Others TITLE Case Studies in Science Education, Volume I: The Case Reports. INSTITUTION Illinois Univ., Urbana. Center for Instructional - Research and Curriculum Evaluation. SPONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C. Directorate for Science Education. REPORT NO NSF-SE-78-74 PUB DATE Jan 78 CONTRACT NSF-C-7621134 NOTE 658p.; For related documents, see SE 026 360, SE 0261 708, ED 152 565 and ED 153 875-880; Contains occasional light and broken type AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 (Stock Number 038-000-00377-1; $7.25) EDRS PRICE MF-$1.16 HC-$35.49 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Case Studies (Education); Curriculum; Educational Research; Elementary Secondail Education; Federal Legislation; Instruction; Instructional Materials; *Mathematics Education; *Science Education; *Social Studies; State Federal Aid; *Teaching Methods" IDENTIFIERS *National Science Foundation ABSTRACT This document presents a collection of field observations, from 11 -sites, submitted as a part of the final report of a project funded by the National Science Foundation to gather data about science, mathematics and social science education in Amerlcad schools. Schools involved a variety of settings: rural-urban, racially diverse, socioeconomically different, and located throughout the United States. Field observers spend 4-15 weeks on site, gathering data. Biographical information on each field observer accompanies his/her case study. (PEB) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can_be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** U.S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION I. WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVEDFROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN -. -

Tips for Families

GRADE 2 | MODULE 3 TIPS FOR FAMILIES WHAT IS MY GRADE 2 STUDENT LEARNING IN MODULE 3? Wit & Wisdom® is our English curriculum. It builds knowledge of key topics in history, science, and literature through the study of excellent texts. By reading and responding to stories and nonfiction texts, we will build knowledge of the following topics: Module 1: A Season of Change Module 2: The American West Module 3: Civil Rights Heroes Module 4: Good Eating In Module 3, we will study a number of strong and brave people who responded to the injustice they saw and experienced. By analyzing texts and art, students answer the question: How can people respond to injustice? OUR CLASS WILL READ THESE BOOKS Picture Books (Informational) ▪ Martin Luther King, Jr. and the March on Washington, Frances E. Ruffin; illustrations, Stephen Marchesi ▪ I Have a Dream, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; paintings, Kadir Nelson ▪ Ruby Bridges Goes to School: My True Story, Ruby Bridges ▪ The Story of Ruby Bridges, Robert Coles; illustrations, George Ford ▪ Separate is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation, Duncan Tonatiuh Poetry ▪ “Words Like Freedom,” Langston Hughes ▪ “Dreams,” Langston Hughes OUR CLASS WILL EXAMINE THIS PHOTOGRAPH ▪ Selma to Montgomery March, Alabama, 1965, James Karales OUR CLASS WILL READ THESE ARTICLES ▪ “Different Voices,” Anna Gratz Cockerille ▪ “When Peace Met Power,” Laura Helwegs OUR CLASS WILL WATCH THESE VIDEOS ▪ “Ruby Bridges Interview” ▪ “Civil Rights – Ruby Bridges” ▪ “The Man Who Changed America” For more resources, -

2008 Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Humanities

200808 ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES CHAIRMAN’S LETTER The President The White House Washington, D.C. 20500 Dear Mr. President: It is my privilege to present to you the 2008 annual report of the National Endowment for the Humanities. At the White House in February, I joined President Bush and Mrs. Bush to launch the largest and most ambitious nationwide initiative in NEH’s history: Picturing America, the newest element of our We the People program. Through Picturing America, NEH is distributing forty reproductions of American art masterpieces to schools and public libraries nationwide—where they will help stu- dents of all ages connect with the people, places, events, and ideas that have shaped our country. The selected works of art represent a broad range of American history and artistic achieve- ment, including Emanuel Leutze’s painting of Washington Crossing the Delaware; Mary Cassatt’s The Boating Party; the Chrysler Building in New York City; Norman Rockwell’s iconic Freedom of Speech; and James Karales’s stunning photo of the Selma-to-Montgomery March for Voting Rights in 1965. Accompanying the reproductions are a teacher’s guide and a dynamic website with ideas for using the images in the study of American history, literature, civics, and other subjects. During the first round of applications for Picturing America awards in the spring of 2008, nearly one-fifth of all the schools and public libraries in America applied for the program. In the fall, the first Picturing America sets arrived at more than 26,000 institutions nationwide, and we opened a second application window for Picturing America awards that will be distributed in 2009. -

Untimely Meditations: Reflections on the Black Audio Film Collective

8QWLPHO\0HGLWDWLRQV5HIOHFWLRQVRQWKH%ODFN$XGLR )LOP&ROOHFWLYH .RGZR(VKXQ Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, Number 19, Summer 2004, pp. 38-45 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\'XNH8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/nka/summary/v019/19.eshun.html Access provided by Birkbeck College-University of London (14 Mar 2015 12:24 GMT) t is no exaggeration to say that the installation of In its totality, the work of John Akomfrah, Reece Auguiste, Handsworth Songs (1985) at Documentall introduced a Edward George, Lina Gopaul, Avril Johnson, David Lawson, and new audience and a new generation to the work of the Trevor Mathison remains terra infirma. There are good reasons Black Audio Film Collective. An artworld audience internal and external to the group why this is so, and any sus• weaned on Fischli and Weiss emerged from the black tained exploration of the Collective's work should begin by iden• cube with a dramatically expanded sense of the historical, poet• tifying the reasons for that occlusion. Such an analysis in turn ic, and aesthetic project of the legendary British group. sets up the discursive parameters for a close hearing and viewing The critical acclaim that subsequently greeted Handsworth of the visionary project of the Black Audio Film Collective. Songs only underlines its reputation as the most important and We can locate the moment when the YBA narrative achieved influential art film to emerge from England in the last twenty cultural liftoff in 1996 with Douglas Gordon's Turner Prize vic• years. It is perhaps inevitable that Handsworth Songs has tended tory. -

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF Mourns the Loss of the Honora

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF mourns the loss of The Honorable John Lewis, an esteemed member of Congress and revered civil rights icon with whom our organization has a deeply personal history. Mr. Lewis passed away on July 17, 2020, following a battle with pancreatic cancer. He was 80 years old. “I don’t know of another leader in this country with the moral standing of Rep. John Lewis. His life and work helped shape the best of our national identity,” said Sherrilyn Ifill, LDF’s President & Director-Counsel. “We revered him not only for his work and sacrifices during the Civil Rights Movement, but because of his unending, stubborn, brilliant determination to press for justice and equality in this country. “There was no cynicism in John Lewis; no hint of despair even in the darkest moments. Instead, he showed up relentlessly with commitment and determination - but also love, and joy and unwavering dedication to the principles of non-violence. He spoke up and sat-in and stood on the front lines – and risked it all. This country – every single person in this country – owes a debt of gratitude to John Lewis that we can only begin to repay by following his demand that we do more as citizens. That we ‘get in the way.’ That we ‘speak out when we see injustice’ and that we keep our ‘eyes on the prize.’” The son of sharecroppers, Mr. Lewis was born on Feb. 21, 1940, outside of Troy, Alabama. He grew up attending segregated public schools in the state’s Pike County and, as a boy, was inspired by the work of civil rights activists, including Dr. -

Remembering the Struggle for Civil Rights – the Greenwood Sites

rallied a crowd of workers set up shop in a building that stood Union Grove M.B. Church protestors in this park on this site. By 1963, local participation in 615 Saint Charles Street with shouts of “We Civil Rights activities was growing, accel- Union Grove was the first Baptist church in want black power!” erated by the supervisors’ decision to halt Greenwood to open its doors to Civil Rights Change Began Here Greenwood was the commodity distribution. The Congress of activities when it participated in the 1963 midpoint of James Racial Equality (CORE), Council of Federated Primary Election Freedom Vote. Comedian GREENWOOD AND LEFLORE COUNTY, MISSISSIPPI Meredith’s “March Organizations (COFO), Southern Christian and activist Dick Gregory spoke at the church Against Fear” from Memphis to Jackson. in the spring of that year as part of his cam- Carmichael and two other marchers had paign to provide food and clothing to those been arrested for pitching tents on a school left in need after Leflore County Supervisors Birth of a Movement campus. By the time they were bailed out, discontinued federal commodities distribution. “In the meetings everything--- more than 600 marchers and local people uncertainty, fear, even desperation--- had gathered in the park, and Carmichael St. Francis Center finds expression, and there is comfort seized the moment to voice the “black 709 Avenue I power” slogan, which fellow SNCC worker This Catholic Church structure served as a and sustenance in talkin‘ ‘bout it.” Willie Ricks had originated. hospital for blacks and a food distribution – Michael Thelwell, SNCC Organizer center in the years before the Civil Rights First SNCC Office Movement. -

Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X Talk It out 17

Writing for Understanding ACTIVITY Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X Talk It Out 17 Overview Materials This Writing for Understanding activity allows students to learn about and write • Transparency 17A a fictional dialogue reflecting the differing viewpoints of Martin Luther King Jr. • Student Handouts and Malcolm X on the methods African Americans should use to achieve equal 17 A –17C rights. Students study written information about either Martin Luther King Jr. • Information Master or Malcolm X and then compare the backgrounds and views of the two men. 17A Students then use what they have learned to assume the roles of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X and debate methods for achieving African American equality. Afterward, students write a dialogue between the two men to reveal their differing viewpoints. Procedures at a Glance • Before class, decide how you will divide students into mixed-ability pairs. Use the diagram at right to determine where they should sit. • In class, tell students that they will write a dialogue reflecting the differing viewpoints of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X on the methods African Americans should use to achieve equal rights. • Divide the class into two groups—one representing each man. Explain that pairs will become “experts” on either Martin Luther King Jr. or Malcolm X. Direct students to move into their correct places. • Give pairs a copy of the appropriate Student Handout 17A. Have them read the information and discuss the “stop and discuss” questions. • Next, place each pair from the King group with a pair from the Malcolm X group. -

Spittin' Truth to the Power While Light Leaping for The

1 SPITTIN’ TRUTH TO THE POWER WHILE LIGHT LEAPING FOR THE PEOPLE By Alyce Smith Cooper and Shammy Dee A La Jolla Playhouse Commission Grade Level: Middle and High School Before You Watch: ● Learn more about La Jolla Playhouse Digital Without Walls (WOW) Artists Alyce Smith Cooper and Shammy Dee and the creative team for this piece. Questions for class discussion or journal: ○ Consider the title for this piece. What do you think this title means? What do you imagine you will be seeing, hearing, and experiencing? ○ When you see the image of a person with their hand in a fist, stretched up towards the sky, what does that evoke for you? Where have you seen this symbol before and what does it mean? ○ Make a list as a class of the fairy tales and stories they have heard as children. Ask the students to consider who is the storyteller and who is the audience for these stories. Which stories did you connect to the most and why? Do you feel like the stories you heard as a kid represented who you are as a person? Why or why not? ○ What do the words sermon, communion, and fellowship mean to you, and in what context do you think of these words? Have the students share their various definitions and ask them why they think the three pieces of SPITTIN’ TRUTH TO THE POWER WHILE LIGHT LEAPING FOR THE PEOPLE may have these titles--what might they expect to see or hear in each piece? (Revisit this question after watching each piece with each term). -

Civil Rights Part 2 1960-75

BIRMINGHAM (1963) SELMA (1965) MALCOLM X CIVIL RIGHTS PART 2 CITY RIOTS (1964-68) 1960-75 . SNCC and SCLC organised peaceful . MLK and SCLC were invited to . Radical beliefs: believed in using . Major riots in US cities e.g. Watts, protests in Birmingham, Alabama (a campaign in Selma, Alabama, where violence if necessary and did not LA (1965) and Chicago (1966). notoriously racist city). voter registration was very low. want integration. Caused by long-term factors such . They knew they would get a reaction . Around 600 began a peaceful march . Like MLK he was well educated and GREENSBORO SIT-INS (1960) as unemployment and poverty. from police chief Bull Connor. from Selma to Montgomery, but an excellent speaker. Usually sparked by incidents of . Connor used police dogs and water were attacked by state troopers. Belonged to radical group Nation of police brutality and hot weather. 4 students held a sit-in at a segregated lunch counter in cannon against the protestors, even Known as ‘Bloody Sunday’ Islam, but left in 1964 after . 1968 Kerner Report said the riots Woolworths, North Carolina. children lots of publicity in favour massive publicity. disagreements with leader. had been caused by discrimination, . This gained massive publicity, of the protesters. President Johnson federalised the . His views softened after he left NOI and officials should do more to help leading to more students joining in. Encouraged sympathy for civil rights National Guard and ordered them to – he began to work with whites and the black community. Also said the . The sit-in inspired others to hold (although some controversy over escort the marchers safely. -

The Promised Land (1967–1968)

EPISODE 10: THE PROMISED LAND (1967–1968) Episode 10 reviews the final months of Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s life and the immediate aftermath of his assassination. This period marked an intensification of the nonviolent struggle in two areas: the struggle against poverty and the efforts to end the Vietnam War. For King, these two issues 1965 became inseparable. Jan. 8 In his State of the Union address, newly elect- By 1967, the United States was deeply ed President Lyndon B. Johnson declares a entrenched in the Vietnam War. Invoking the fear of “War on Poverty” campaign communist expansion and the threat it posed to Aug. 4 The US Congress passes the “Gulf of Tonkin democracy, President Lyndon B. Johnson increased Resolution.” The resolution opened the way to the number of US troops in Vietnam. In response, large-scale involvement of US forces in some civil rights leaders charged that President Vietnam Johnson’s domestic “war on poverty” was falling vic- 1966 tim to US war efforts abroad. Aug. President Johnson authorizes the deployment Episode 10 opens with King’s internal dilemma of more troops to Vietnam, bringing the total about finding a proper way to publicly denounce to 429,000 America’s involvement in Vietnam. In a speech 1967 delivered on April 4, 1967, at Riverside Church in New York, King told the gathered clergy that it was Apr. 4 At Riverside Church in New York City, King “time to break the silence” on Vietnam. Drawing publicly denounces the war in Vietnam connections between the resources spent on the war Jul. -

Social Studies TOPIC U.S

2018-2019 Reading List Social Studies TOPIC U.S. Civil Rights Movements: Fulfilling a Nation’s Promise PRIMARY READING SELECTION The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation, by Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff Vintage; (2007) ISBN: 978-0679735656! Available from Texas Educational Paperbacks, Inc ! 800-443-2078 www.tepbooks.com List price: $17.00, TEP UIL price: $11.05 plus shipping Also available from most online book sellers SUPPLEMENTAL READING MATERIAL Supreme Court Cases • Dred Scott v. Sanford (1856) • Roe v. Wade (1973) • Civil Rights Cases (1883) • Lau v. Nichols (1974) • Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886) • Plyler v. Doe (1982) • Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) • Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson (1986) • Missouri ex el Gaines v. Canada (1938) • Bowers v. Hardwick (1986) • Shelley v. Kraemer (1948) • UAW v. Johnson Controls (1991) • Sweatt v. Painter (1950) • Franklin v. Gwinnett County Public Schools • Briggs v. Elliot (1952) (1992) • Hernandez v. Texas (1954) • US v. Virginia (1996) • Brown v. Board of Education (1954) • Romer v. Evans (1996) • Brown v. Board of Education II (1955) • Faragher v. City of Boca Raton (1998) • Browder v Gayle (1956) • Lawrence v. Texas (2003) • Heart of Atlanta Motel Inc. v. U.S. (1964) • Shelby County v. Holder (2013) • Loving v. Virginia (1967) • United States v. Windsor (2013) • Jones v. Mayer Co. (1968) • Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. (2014) • Griggs v. Duke Power Co. (1971) • Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) Legislation th th th th • Title IX of the Federal Education • 5 , 14 , 15 , 24 Amendments • Civil Rights Act of 1875 Amendments (1972) • Civil Rights Act of 1957 • Equal Rights Amendment (1972) • Civil Rights Act of 1964 • Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987 • Voting Rights Act (1965) • Americans with Disabilities Act of • Fair Housing Act (1968) 1990 Speeches & Movement Documents • The Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments • I’ve Been to the Mountaintop, Martin Luther (1848) King, Jr.