Eyesontheprize-Studyguide 202.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Full Resource List

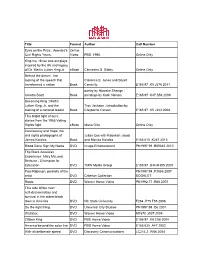

Title Format Author Call Number Eyes on the Prize : America's Online Civil Rights Years. Video PBS, 1990. Online Only King me : three one-act plays inspired by the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. eBook Clinnesha D. Sibley. Online Only Behind the dream : the making of the speech that Clarence B. Jones and Stuart transformed a nation Book Connelly. E185.97 .K5 J576 2011 poetry by Ntozake Shange ; Coretta Scott Book paintings by Kadir Nelson. E185.97 .K47 S53 2009 Becoming King : Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Troy Jackson ; introduction by making of a national leader Book Clayborne Carson. E185.97 .K5 J343 2008 This bright light of ours: stories from the 1965 Voting Rights fight eBook Maria Gitin. Online Only Controversy and Hope: the civil rights photographs of Julian Cox with Rebekah Jacob James Karales Book and Monica Karales E185.615 .K287 2013 Blood Done Sign My Name DVD Image Entertainment PN1997.99 .B59645 2010 The Black American Experience: Mary McLeod Bethune - Champion for Education DVD TMW Media Group E185.97 .B34 M385 2009 Paul Robeson: portraits of the PN1997.99 .P3885 2007 artist DVD Criterion Collection BOOKLET Roots DVD Warner Home Video PN1992.77 .R66 2007 This side of the river: self-determination and survival in the oldest black town in America DVD NC State University F264 .P75 T55 2006 Do the right thing DVD Universal City Studios PN1997.99 .D6 2001 Wattstax DVD Warner Home Video M1670 .W37 2004 Citizen King DVD PBS Home Video E185.97 .K5 C58 2004 America beyond the color line DVD PBS Home Video E185.625 .A47 2003 With all deliberate speed DVD Discovery Communications LC214.2 .W58 2004 Chisholm '72: Unbought and 20th Century Fox Home Unbossed DVD Entertainmen E840.8 .C48 C55 2004 Between the World and Me Book Ta-Nehisi Coates E185.615 .C6335 2015 The autobiography of Malcolm X Book Malcolm X E185.97 .L5 A3 2015 Dreams from my father : a story of race and inheritance Book Barack Obama E185.97 .O23 A3 2007 Up from slavery : an autobiography Book Booker T. -

Tips for Families

GRADE 2 | MODULE 3 TIPS FOR FAMILIES WHAT IS MY GRADE 2 STUDENT LEARNING IN MODULE 3? Wit & Wisdom® is our English curriculum. It builds knowledge of key topics in history, science, and literature through the study of excellent texts. By reading and responding to stories and nonfiction texts, we will build knowledge of the following topics: Module 1: A Season of Change Module 2: The American West Module 3: Civil Rights Heroes Module 4: Good Eating In Module 3, we will study a number of strong and brave people who responded to the injustice they saw and experienced. By analyzing texts and art, students answer the question: How can people respond to injustice? OUR CLASS WILL READ THESE BOOKS Picture Books (Informational) ▪ Martin Luther King, Jr. and the March on Washington, Frances E. Ruffin; illustrations, Stephen Marchesi ▪ I Have a Dream, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; paintings, Kadir Nelson ▪ Ruby Bridges Goes to School: My True Story, Ruby Bridges ▪ The Story of Ruby Bridges, Robert Coles; illustrations, George Ford ▪ Separate is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation, Duncan Tonatiuh Poetry ▪ “Words Like Freedom,” Langston Hughes ▪ “Dreams,” Langston Hughes OUR CLASS WILL EXAMINE THIS PHOTOGRAPH ▪ Selma to Montgomery March, Alabama, 1965, James Karales OUR CLASS WILL READ THESE ARTICLES ▪ “Different Voices,” Anna Gratz Cockerille ▪ “When Peace Met Power,” Laura Helwegs OUR CLASS WILL WATCH THESE VIDEOS ▪ “Ruby Bridges Interview” ▪ “Civil Rights – Ruby Bridges” ▪ “The Man Who Changed America” For more resources, -

2008 Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Humanities

200808 ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES CHAIRMAN’S LETTER The President The White House Washington, D.C. 20500 Dear Mr. President: It is my privilege to present to you the 2008 annual report of the National Endowment for the Humanities. At the White House in February, I joined President Bush and Mrs. Bush to launch the largest and most ambitious nationwide initiative in NEH’s history: Picturing America, the newest element of our We the People program. Through Picturing America, NEH is distributing forty reproductions of American art masterpieces to schools and public libraries nationwide—where they will help stu- dents of all ages connect with the people, places, events, and ideas that have shaped our country. The selected works of art represent a broad range of American history and artistic achieve- ment, including Emanuel Leutze’s painting of Washington Crossing the Delaware; Mary Cassatt’s The Boating Party; the Chrysler Building in New York City; Norman Rockwell’s iconic Freedom of Speech; and James Karales’s stunning photo of the Selma-to-Montgomery March for Voting Rights in 1965. Accompanying the reproductions are a teacher’s guide and a dynamic website with ideas for using the images in the study of American history, literature, civics, and other subjects. During the first round of applications for Picturing America awards in the spring of 2008, nearly one-fifth of all the schools and public libraries in America applied for the program. In the fall, the first Picturing America sets arrived at more than 26,000 institutions nationwide, and we opened a second application window for Picturing America awards that will be distributed in 2009. -

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF Mourns the Loss of the Honora

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF mourns the loss of The Honorable John Lewis, an esteemed member of Congress and revered civil rights icon with whom our organization has a deeply personal history. Mr. Lewis passed away on July 17, 2020, following a battle with pancreatic cancer. He was 80 years old. “I don’t know of another leader in this country with the moral standing of Rep. John Lewis. His life and work helped shape the best of our national identity,” said Sherrilyn Ifill, LDF’s President & Director-Counsel. “We revered him not only for his work and sacrifices during the Civil Rights Movement, but because of his unending, stubborn, brilliant determination to press for justice and equality in this country. “There was no cynicism in John Lewis; no hint of despair even in the darkest moments. Instead, he showed up relentlessly with commitment and determination - but also love, and joy and unwavering dedication to the principles of non-violence. He spoke up and sat-in and stood on the front lines – and risked it all. This country – every single person in this country – owes a debt of gratitude to John Lewis that we can only begin to repay by following his demand that we do more as citizens. That we ‘get in the way.’ That we ‘speak out when we see injustice’ and that we keep our ‘eyes on the prize.’” The son of sharecroppers, Mr. Lewis was born on Feb. 21, 1940, outside of Troy, Alabama. He grew up attending segregated public schools in the state’s Pike County and, as a boy, was inspired by the work of civil rights activists, including Dr. -

Eyesontheprize-Studyguide 207.Pdf

A Blackside Publication A Study Guide Written by Facing History and Ourselves Copyright © 2006 Blackside, Inc. All rights reserved. Cover photos:(Signature march image) James Karales; (Front cover, left inset image) © Will Counts, Used with permission of Vivian Counts; (All other inset images) © Bettmann/Corbis Design by Planet Studio For permissions information, please see page 225 FOREWORD REP. JOHN LEWIS 5th Congressional District, Georgia The documentary series you are about to view is the story of how ordinary people with extraordinary vision redeemed “If you will protest courageously and democracy in America. It is a testament to nonviolent passive yet with dignity and …. love, when resistance and its power to reshape the destiny of a nation and the history books are written in future generations, the historians will the world. And it is the chronicle of a people who challenged have to pause and say, ‘There lies a one nation’s government to meet its moral obligation to great people, a black people, who humanity. injected new meaning and dignity We, the men, women, and children of the civil rights move- into the very veins of civilization.’ ment, truly believed that if we adhered to the discipline and This is our challenge and our philosophy of nonviolence, we could help transform America. responsibility.” We wanted to realize what I like to call, the Beloved Martin Luther King, Jr., Community, an all-inclusive, truly interracial democracy based Dec. 31, 1955 on simple justice, which respects the dignity and worth of every Montgomery, Alabama. human being. Central to our philosophical concept of the Beloved Community was the willingness to believe that every human being has the moral capacity to respect each other. -

The Promised Land (1967–1968)

EPISODE 10: THE PROMISED LAND (1967–1968) Episode 10 reviews the final months of Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s life and the immediate aftermath of his assassination. This period marked an intensification of the nonviolent struggle in two areas: the struggle against poverty and the efforts to end the Vietnam War. For King, these two issues 1965 became inseparable. Jan. 8 In his State of the Union address, newly elect- By 1967, the United States was deeply ed President Lyndon B. Johnson declares a entrenched in the Vietnam War. Invoking the fear of “War on Poverty” campaign communist expansion and the threat it posed to Aug. 4 The US Congress passes the “Gulf of Tonkin democracy, President Lyndon B. Johnson increased Resolution.” The resolution opened the way to the number of US troops in Vietnam. In response, large-scale involvement of US forces in some civil rights leaders charged that President Vietnam Johnson’s domestic “war on poverty” was falling vic- 1966 tim to US war efforts abroad. Aug. President Johnson authorizes the deployment Episode 10 opens with King’s internal dilemma of more troops to Vietnam, bringing the total about finding a proper way to publicly denounce to 429,000 America’s involvement in Vietnam. In a speech 1967 delivered on April 4, 1967, at Riverside Church in New York, King told the gathered clergy that it was Apr. 4 At Riverside Church in New York City, King “time to break the silence” on Vietnam. Drawing publicly denounces the war in Vietnam connections between the resources spent on the war Jul. -

Social Studies TOPIC U.S

2018-2019 Reading List Social Studies TOPIC U.S. Civil Rights Movements: Fulfilling a Nation’s Promise PRIMARY READING SELECTION The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation, by Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff Vintage; (2007) ISBN: 978-0679735656! Available from Texas Educational Paperbacks, Inc ! 800-443-2078 www.tepbooks.com List price: $17.00, TEP UIL price: $11.05 plus shipping Also available from most online book sellers SUPPLEMENTAL READING MATERIAL Supreme Court Cases • Dred Scott v. Sanford (1856) • Roe v. Wade (1973) • Civil Rights Cases (1883) • Lau v. Nichols (1974) • Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886) • Plyler v. Doe (1982) • Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) • Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson (1986) • Missouri ex el Gaines v. Canada (1938) • Bowers v. Hardwick (1986) • Shelley v. Kraemer (1948) • UAW v. Johnson Controls (1991) • Sweatt v. Painter (1950) • Franklin v. Gwinnett County Public Schools • Briggs v. Elliot (1952) (1992) • Hernandez v. Texas (1954) • US v. Virginia (1996) • Brown v. Board of Education (1954) • Romer v. Evans (1996) • Brown v. Board of Education II (1955) • Faragher v. City of Boca Raton (1998) • Browder v Gayle (1956) • Lawrence v. Texas (2003) • Heart of Atlanta Motel Inc. v. U.S. (1964) • Shelby County v. Holder (2013) • Loving v. Virginia (1967) • United States v. Windsor (2013) • Jones v. Mayer Co. (1968) • Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. (2014) • Griggs v. Duke Power Co. (1971) • Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) Legislation th th th th • Title IX of the Federal Education • 5 , 14 , 15 , 24 Amendments • Civil Rights Act of 1875 Amendments (1972) • Civil Rights Act of 1957 • Equal Rights Amendment (1972) • Civil Rights Act of 1964 • Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987 • Voting Rights Act (1965) • Americans with Disabilities Act of • Fair Housing Act (1968) 1990 Speeches & Movement Documents • The Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments • I’ve Been to the Mountaintop, Martin Luther (1848) King, Jr. -

Faulkner & Yoknapatawpha Conference 2013

the the newsletter of the Center for the study of southern Culture • spring 2013 the university of mississippi Faulkner & Yoknapatawpha Conference 2013 “Faulkner and the Black Literatures of the Americas” An impressive response to the call for papers for “Faulkner tablists will join the four invited keynote speakers and the and the Black Literatures of the Americas” has yielded 12 new featured panel of African American poets (both detailed in sessions featuring nearly three dozen speakers for the confer- earlier issues of the Register) to place Faulkner’s life and work ence, which will take place July 21–25, 2013, on the campus in conversation with a distinguished gallery of writers, art- of the University of Mississippi. These panelists and round- ists, and intellectual figures from African American and Afro- Caribbean culture, including Charles Waddell Chesnutt, W.E.B. Du Bois, Jean Toomer, painter William H. Johnson, Claude McKay, Delta bluesman Charley Patton, Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Wright, C.L.R. James, Ralph Ellison, Frantz Fanon, James Baldwin, Édouard Glissant, Marie Vieux- Chauvet, Toni Morrison, Randall Kenan, Suzan-Lori Parks, Edwidge Danticat, Edward P. Jones, Olympia Vernon, Natasha Trethewey, the editors and readers of Ebony magazine, and the writers and characters of the HBO series The Wire. In addi- tion, a roundtable scheduled for the opening afternoon of the conference will reflect on the legacies of the late Noel E. Polk as a teacher, critic, editor, collaborator, and longtime friend of the Faulkner & Yoknapatawpha Conference. Also selected through the call for papers was keynote speaker Tim A. Ryan, associate professor of English at Northern Illinois University and author of Calls and Responses: The American Novel of Slavery since “Gone with the Wind.” Professor Ryan’s keynote address is entitled “‘Go to Jail about This Spoonful’: Narcotic Determinism and Human Agency in ‘That Evening Sun’ and the Delta Blues.” This will be Professor Ryan’s first appearance at Faulkner & Yoknapatawpha. -

The Contemporary Rhetoric About Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X in the Post-Reagan Era

ABSTRACT THE CONTEMPORARY RHETORIC ABOUT MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., AND MALCOLM X IN THE POST-REAGAN ERA by Cedric Dewayne Burrows This thesis explores the rhetoric about Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X in the late 1980s and early 1990s, specifically looking at how King is transformed into a messiah figure while Malcolm X is transformed into a figure suitable for the hip-hop generation. Among the works included in this analysis are the young adult biographies Martin Luther King: Civil Rights Leader and Malcolm X: Militant Black Leader, Episode 4 of Eyes on the Prize II: America at the Racial Crossroads, and Spike Lee’s 1992 film Malcolm X. THE CONTEMPORARY RHETORIC ABOUT MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., AND MALCOLM X IN THE POST-REAGAN ERA A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English by Cedric Dewayne Burrows Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2005 Advisor_____________________ Morris Young Reader_____________________ Cynthia Leweicki-Wison Reader_____________________ Cheryl L. Johnson © Cedric D. Burrows 2005 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One A Dead Man’s Dream: Martin Luther King’s Representation as a 10 Messiah and Prophet Figure in the Black American’s of Achievement Series and Eyes on the Prize II: America at the Racial Crossroads Chapter Two Do the Right Thing by Any Means Necessary: The Revival of Malcolm X 24 in the Reagan-Bush Era Conclusion 39 iii THE CONTEMPORARY RHETORIC ABOUT MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., AND MALCOLM X IN THE POST-REAGAN ERA Introduction “What was Martin Luther King known for?” asked Mrs. -

Lead Wit & Wisdom Resource Packet

Lead Wit & Wisdom® Resource Packet Professional Development Lead Wit & Wisdom Resource Packet WIT & WISDOM® Contents Wit & Wisdom K–8 Modules at a Glance .................................................................. 1 Kindergarten Module Synopses ............................................................................... 3 Grade 1 Module Synopses ...................................................................................... 7 Grade 2 Module Synopses ..................................................................................... 11 Grade 3 Module Synopses .....................................................................................15 Grade 4 Module Synopses .....................................................................................19 Grade 5 Module Synopses .................................................................................... 23 Grade 6 Module Synopses .................................................................................... 27 Grade 7 Module Synopses .....................................................................................31 Grade 8 Module Synopses .................................................................................... 35 Copyright © 2019 Great Minds® Lead Wit & Wisdom Resource Packet • K–8 Modules at a Glance WIT & WISDOM® Wit & Wisdom® K–8 Modules at a Glance Module 1 Module 2 Module 3 Module 4 The Five Senses Once Upon a Farm America, Then and Now The Continents How do our senses help us What makes a good story? How has life in America What makes -

Boston College Bulletin, Law, 1949 Boston College

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Bulletin 4-1-1949 Boston College Bulletin, Law, 1949 Boston College Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bcbulletin Part of the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Boston College, "Boston College Bulletin, Law, 1949" (1949). Boston College Bulletin. Book 21. http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bcbulletin/21 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Bulletin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "]) 0 h.(} t '('"' -e Vtt\.. 6 "-+ €.. ~'-/ -e Y...,S APRIL, 1.94.9 Volume XXI Number 5 inntnu C!in llt gt iullttiu THE LAW SCHOOL CATALOGUE 1.948-1.94.9 ANNOUNCEMENT 1.94.9-1.950 / THE BOSTON COLLEGE LAW SCHOOL EIGHTEEN TREMONT STREET BosToN 8, MAssACHUSETTS THE BOSTON COLLEGE BULLETIN Publis ked by BOSTON COLLEGE University Heights Chestnut Hill Newton, Massachusetts Entered as second-class matter February 28, 1929 in the post office at Boston, Massachusetts under the Act of August 24, 1912. Bulletins issued in each volume: No. 1, February, the School of Arts and Sciences, Chestnut Hill; No. 2, February, the School of Business Administration, Chest nut Hill; No. 3, March, the General University Catalogue; No. 4, April, the Summer School, Chestnut Hill; No. 5, April, the Law School, Boston; No. 6, April, the School of Social Work, Boston; No. 7, July, the School of Arts and Sciences Intown, Boston; No. -

More Eyes on the Prize: Variability in White Americans' Perceptions Of

More Eyes on the Prize: Variability in White Americans’ Perceptions of Progress Toward Racial Equality Amanda B. Brodish Paige C. Brazy Patricia G. Devine University of Wisconsin–Madison Much recent research suggests that Whites and non- How much progress has our nation made toward racial Whites think differently about issues of race in contem- equality? And, against what standard should this judg- porary America. For example, Eibach and Ehrlinger ment be made? This issue is the topic of heated debate, (2006) recently demonstrated that Whites perceive that with many claiming that the nation has made substan- more progress toward racial equality has been made as tial progress toward racial equality, whereas others compared to non-Whites. The authors of this article counter that we are far from achieving the ideal of racial sought to extend Eibach and Ehrlinger’s analysis. To equality. One’s position in this debate will likely have this end, they found that differences in Whites’ and non- consequences for whether or not one believes steps are Whites’ perceptions of racial progress can be explained needed to achieve racial equality. by the reference points they use for understanding As the public debate continues, social scientists have progress toward racial equality (Study 1). Furthermore, been explicitly interested in how people think about they demonstrated that there is variability in White issues of race and racial equality (e.g., Eibach & people’s perceptions of racial progress that can be Ehrlinger, 2006; Eibach & Keegan, 2006; Haley & explained by self-reported racial prejudice (Studies 1 Sidanius, 2006; Lowery, Unzueta, Knowles, & Goff, and 2).