The Germans in Western Canada, a Vanishing People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A C C E P T E

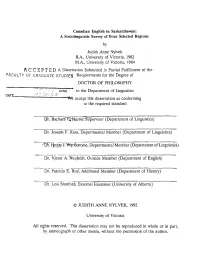

Canadian English in Saskatchewan: A Sociolinguistic Survey of Four Selected Regions by Judith Anne Nylvek B.A., University of Victoria, 1982 M.A., University of Victoria, 1984 ACCEPTE.D A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY .>,« 1,^ , I . I l » ' / DEAN in the Department of Linguistics o ate y " /-''-' A > ' We accept this dissertation as conforming to the required standard Xjx. BarbarSTj|JlA^-fiVSu^rvisor (Department of Linguistics) Dr. Joseph F. Kess, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) CD t. Herijy J, WgrKentyne, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) _________________________ Dr. Victor A. 'fiJeufeldt, Outside Member (Department of English) _____________________________________________ Dr. Pajtricia E. Ro/, Additional Member (Department of History) Dr. Lois Stanford, External Examiner (University of Alberta) © JUDITH ANNE NYLVEK, 1992 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or other means, without the permission of the author. Supervisor: Dr. Barbara P. Harris ABSTRACT The objective of this study is to provide detailed information regarding Canadian English as it is spoken by English-speaking Canadians who were born and raised in Saskatchewan and who still reside in this province. A data base has also been established which will allow real time comparison in future studies. Linguistic variables studied include the pronunciation of several individual lexical items, the use of lexical variants, and some aspects of phonological variation. Social variables deemed important include age, sex, urbanlrural, generation in Saskatchewan, education, ethnicity, and multilingualism. The study was carried out using statistical methodology which provided the framework for confirmation of previous findings and exploration of unknown relationships. -

Pawlowka) Community

50th Year of Paveleni (Pawlowka) Community Source: Deutscher Volkskalender für Bessarabien – 1938 Tarutino Press and Printed by Deutschen Zeitung Bessarabiens Pages 76-85 Translated by: Allen E. Konrad March, 2016 Internet Location: urn:nbn:de:bvb:355-ubr14070-7 [Note: Comments in square brackets in the document are those of the translator.] ================================================================ [Translation Begins] The Community of Paveleni (Pawlowka) Cetatea-Alba (Akkerman) District, Bessarabia On its 50th Year of Existence (1888-1938) by Alexander Mutschaler, Mannsburg It is Laudable, Christian, beautiful and comforting, That a person at no time forgets— Those loving, caring ancestors, Who lived and worked before us! Degener. I. The Good Old Time Just as the flat expanse, astounding to us due to its vastness, was given to us in the former Russian Empire, so also in regards to the private sector, the dimensions of the private land ownership in concentrated hands seemed fantastic in our terms, huge plots of agricultural land (Latifundien) of 30-50,000 Dessjatinen [1 dessjatin = 2.7 acres/1.09 hectares] and more were not uncommon. Also in southern Bessarabia, the so-called Budjak, there were owners of tens of thousands of Dessjatinen of land. The land expanse in the extreme southeastern corner of Bessarabia, on the Black Sea, Dniester Liman and Dniester River up to Bender (Tighina) were awarded, after the transition of Bessarabia to Russia (1812), mainly to highly placed personalities and dignitaries of the Empire; namely: Prince Demidow, Prince Wolkonsky, Count Tolstoi, Prince Trubezkoi, and others. The Demidow family had about 30,000 dessjatinen. of land here on the Black Sea, including the salt estuary which provides the Budaky health resort with the medicated iodine mud which has attracted visitors from all parts of Russia for the past 40 years. -

A Finding Aid to the Emigration And

A Finding Aid to the Emigration and Immigration Pamphlets Shortt JV 7225 .E53 prepared by Glen Makahonu k Shortt Emigration and Immi gration Pamphlets JV 7225 .E53 This collection contains a wide variety of materials on the emigration and immigration issue in Canada, especially during the period of the early 20th century. Two significant groupings of material are: (1) The East Indians in Canada, which are numbered 24 through 50; and (2) The Fellowship of the Maple Leaf, which are numbered 66 through 76. 1. Atlantica and Iceland Review. The Icelandic Settlement in Cdnada. 1875-1975. 2. Discours prononce le 25 Juin 1883, par M. Le cur6 Labelle sur La Mission de la Race Canadienne-Francaise en Canada. Montreal, 1883. 3. Immigration to the Canadian Prairies 1870-1914. Ottawa: Information Canada, 19n. 4. "The Problem of Race", The Democratic Way. Vol. 1, No. 6. March 1944. Ottawa: Progressive Printers, 1944. 5. Openings for Capital. Western Canada Offers Most Profitable Field for Investment of Large or Small Sums. Winnipeg: Industria1 Bureau. n.d. 6. A.S. Whiteley, "The Peopling of the Prairie Provinces of Canada" The American Journal of Sociology. Vol. 38, No. 2. Sept. 1932. 7. Notes on the Canadian Family Tree. Ottawa: Dept. of Citizenship and Immigration. 1960. 8. Lawrence and LaVerna Kl ippenstein , Mennonites in Manitoba Thei r Background and Early Settlement. Winnipeg, 1976. 9. M.P. Riley and J.R. Stewart, "The Hutterites: South Dakota's Communal Farmers", Bulletin 530. Feb. 1966. 10. H.P. Musson, "A Tenderfoot in Canada" The Wide World Magazine Feb. 1927. 11. -

A Thesis for the Degree of University of Regina Regina, Saskatchewan

Hitched to the Plow: The Place of Western Pioneer Women in Innisian Staple Theory A Thesis Subrnitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Sociology University of Regina by Sandxa Lynn Rollings-Magnusson Regina, Saskatchewan June, 1997 Copyright 1997: S.L. Rollings-Magnusson 395 Wellington Street 395, nie Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pemettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seli reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de micro fi ch el^, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othemîse de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Romantic images of the opening of the 'last best west' bring forth visions of hearty pioneer men and women with children in hand gazing across bountiful fields of golden wheat that would make them wealthy in a land full of promise and freedom. The reality, of course, did not match the fantasy. -

Persecution of the Czech Minority in Ukraine at the Time of the Great Purge1

ARTICLES Persecution of the Czech Minority in Ukraine 8 Mečislav BORÁK at the Time of the Great Purge Persecution of the Czech Minority in Ukraine at the Time of the Great Purge1 prof. Mečislav BORÁK Abstract In its introduction, the study recalls the course of Czech emigration to Ukraine and the formation of the local Czech minority from the mid-19th century until the end of 1930s. Afterwards, it depicts the course of political persecution of the Czechs from the civil war to the mid-1930s and mentions the changes in Soviet national policy. It characterizes the course of the Great Purge in the years 1937–1938 on a national scale and its particularities in Ukraine, describes the genesis of the repressive mechanisms and their activities. In this context, it is focused on the NKVD’s national operations and the repression of the Czechs assigned to the Polish NKVD operation in the early spring of 1938. It analyses the illegal executions of more than 660 victims, which was roughly half of all Czechs and Czechoslovak citizens executed for political reasons in the former Soviet Union, both from time and territorial point of view, including the national or social-professional structure of the executed, roughly compared to Moscow. The general conclusions are illustrated on examples of repressive actions and their victims from the Kiev region, especially from Kiev, and Mykolajivka community, not far from the centre of the Vinnycko area, the most famous centre of Czech colonization in eastern Podolia. In detail, it analyses the most repressive action against the Czechs in Ukraine which took place in Zhytomyr where on 28 September 1938, eighty alleged conspirators were shot dead, including seventy-eight Czechs. -

The Causes of Ukrainian-Polish Ethnic Cleansing 1943 Author(S): Timothy Snyder Source: Past & Present, No

The Past and Present Society The Causes of Ukrainian-Polish Ethnic Cleansing 1943 Author(s): Timothy Snyder Source: Past & Present, No. 179 (May, 2003), pp. 197-234 Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of The Past and Present Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3600827 . Accessed: 05/01/2014 17:29 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Oxford University Press and The Past and Present Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Past &Present. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 137.110.33.183 on Sun, 5 Jan 2014 17:29:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE CAUSES OF UKRAINIAN-POLISH ETHNIC CLEANSING 1943* Ethniccleansing hides in the shadow of the Holocaust. Even as horrorof Hitler'sFinal Solution motivates the study of other massatrocities, the totality of its exterminatory intention limits thevalue of the comparisons it elicits.Other policies of mass nationalviolence - the Turkish'massacre' of Armenians beginningin 1915, the Greco-Turkish'exchanges' of 1923, Stalin'sdeportation of nine Soviet nations beginning in 1935, Hitler'sexpulsion of Poles and Jewsfrom his enlargedReich after1939, and the forcedflight of Germans fromeastern Europein 1945 - havebeen retrievedfrom the margins of mili- tary and diplomatichistory. -

Ukraine in World War II

Ukraine in World War II. — Kyiv, Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, 2015. — 28 p., ill. Ukrainians in the World War II. Facts, figures, persons. A complex pattern of world confrontation in our land and Ukrainians on the all fronts of the global conflict. Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance Address: 16, Lypska str., Kyiv, 01021, Ukraine. Phone: +38 (044) 253-15-63 Fax: +38 (044) 254-05-85 Е-mail: [email protected] www.memory.gov.ua Printed by ПП «Друк щоденно» 251 Zelena str. Lviv Order N30-04-2015/2в 30.04.2015 © UINR, texts and design, 2015. UKRAINIAN INSTITUTE OF NATIONAL REMEMBRANCE www.memory.gov.ua UKRAINE IN WORLD WAR II Reference book The 70th anniversary of victory over Nazism in World War II Kyiv, 2015 Victims and heroes VICTIMS AND HEROES Ukrainians – the Heroes of Second World War During the Second World War, Ukraine lost more people than the combined losses Ivan Kozhedub Peter Dmytruk Nicholas Oresko of Great Britain, Canada, Poland, the USA and France. The total Ukrainian losses during the war is an estimated 8-10 million lives. The number of Ukrainian victims Soviet fighter pilot. The most Canadian military pilot. Master Sergeant U.S. Army. effective Allied ace. Had 64 air He was shot down and For a daring attack on the can be compared to the modern population of Austria. victories. Awarded the Hero joined the French enemy’s fortified position of the Soviet Union three Resistance. Saved civilians in Germany, he was awarded times. from German repression. the highest American The Ukrainians in the Transcarpathia were the first during the interwar period, who Awarded the Cross of War. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University Press Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00830-4

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00830-4 - The German Minority in Interwar Poland Winson Chu Index More information Index Agrarian conservativism, 71 Beyer, Hans Joachim, 212 Alldeutscher Verband. See Pan-German Bielitz. See Bielsko League Bielitzer Kreis, 174 Allgemeiner Schulverein, 36 Bielsko, 25, 173, 175, 203 Alltagsgeschichte, 10 Bielsko Germans, 108, 110, 111 Ammende, Ewald, 136 Bierschenk, Theodor, 137, 216, 224 Anschluß question, 51, 52 Bjork, James, 17 Anti-Communism, 165 Blachetta-Madajczyk, Petra, 9, 130, 136 Anti-Germanism, 214, 244, 245 Black Palm Sunday, 213–217 Anti-Semitism, 38, 79, 151, 159, 166, 178, Blanke, Richard, 9, 65, 76, 90, 136, 162 212, 215, 244, 260 Boehm, Max Hildebert, 31, 39, 46, 54, 88, Association for Germandom Abroad. See 97, 99, 110, 205 Verein fur¨ das Deutschtum im Ausland Border Germans and Germans Abroad, 44 Auslandsdeutsche, 98, 206.SeealsoReich Brackmann, Albert, 45, 208 Germans; Reich Germans, former Brauer, Leo, 221 Auslands-Organisation der NSDAP, 180, Brest-Litovsk Treaty, 42 205 Breuler, Otto, 103 Austria, 34, 165, 173, 207 Breyer, Albert, 153, 155, 212 annexation of, 51 Breyer, Richard, 155, 216, 272, 274 Austrian Silesia. See Teschen Silesia Briand, Aristide, 50 Bromberg. See Bydgoszcz Baechler, Christian, 53 Bromberg Bloody Sunday. See Bromberger Baltic Germans, 268 Blutsonntag Baltic Institute, 45, 208 Bromberger Blutsonntag, 4, 249 Bartkiewicz, Zygmunt, 118 Bromberger Volkszeitung, 134 Bauernverein, 72 Broszat, Martin, 205 Behrends, Hermann, 231 Brubaker, Rogers, 9, 26, 34, 63, 86, -

Appanage Russia

0 BACKGROUND GUIDE: APPANAGE RUSSIA 1 BACKGROUND GUIDE: APPANAGE RUSSIA Hello delegates, My name is Paul, and I’ll be your director for this year. Working with me are your moderator, Tristan; your crisis manager, Davis; and your analysts, Lawrence, Lilian, Philip, and Sofia. We’re going to be working together to make this council as entertaining and educational (yeah yeah, I know) as possible. A bit about me? I am a third year student studying archaeology, and this is also my third year doing UTMUN. Now enough about me. Let’s talk about something far more interesting: Russia. Russian history is as brutal as the land itself, especially during our time of study. Geography sets the stage with freezing winters and mud-ridden summers. This has huge effects on how Russia’s economy and society functions. Coupled with that are less-than-neighbourly neighbours: the power- hungry nations of western and central Europe, The Byzantine Empire (a consistent love- hate partner), and (big surprise) various nomadic groups, one of which would eventually pose quite a problem for the idea of Russian independence. Uh oh, it looks like it’s suddenly 1300 and all of you are Russian Princess.You are all under the rule of Toqta Khan of the Golden Horde (Halperin, 2009), one of the successor states to Genghis Khan’s massive empire. Bummer. But, there is hope: through working together and with wise reactions to the crises that will inevitably come your way, you might just be able shake off the Tatar Yoke. Of course, your problems are not so limited. -

Germany's Policy Vis-À-Vis German Minority in Romania

T.C. TURKISH- GERMAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES EUROPE AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT GERMANY’S POLICY VIS-À-VIS GERMAN MINORITY IN ROMANIA MASTER’S THESIS Yunus MAZI ADVISOR Assoc. Prof. Dr. Enes BAYRAKLI İSTANBUL, January 2021 T.C. TURKISH- GERMAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES EUROPE AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT GERMANY’S POLICY VIS-À-VIS GERMAN MINORITY IN ROMANIA MASTER’S THESIS Yunus MAZI 188101023 ADVISOR Assoc. Prof. Dr. Enes BAYRAKLI İSTANBUL, January 2021 I hereby declare that this thesis is an original work. I also declare that I have acted in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct at all stages of the work including preparation, data collection and analysis. I have cited and referenced all the information that is not original to this work. Name - Surname Yunus MAZI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. Enes Bayraklı. Besides my master's thesis, he has taught me how to work academically for the past two years. I would also like to thank Dr. Hüseyin Alptekin and Dr. Osman Nuri Özalp for their constructive criticism about my master's thesis. Furthermore, I would like to thank Kazım Keskin, Zeliha Eliaçık, Oğuz Güngörmez, Hacı Mehmet Boyraz, Léonard Faytre and Aslıhan Alkanat. Besides the academic input I learned from them, I also built a special friendly relationship with them. A special thanks goes to Burak Özdemir. He supported me with a lot of patience in the crucial last phase of my research to complete the thesis. In addition, I would also like to thank my other friends who have always motivated me to successfully complete my thesis. -

Introduction

Introduction R a y B r a n d o n a n d W e n d y L o w e r Before the Second World War, the Jews of Ukraine constituted one of the largest Jewish populations in Europe.1 They were without a doubt the largest Jewish population within the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union.2 And between July 1940 and June 1941—af ter Stalin occupied the interwar Polish territories of eastern Gali cia and western Volhynia as well as the interwar Romanian territo ries of northern Bukovina and southern Bessarabia—the number of Jews in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (UkrSSR) rose to at least 2.45 million persons, thus making it for a brief period home to the largest Jewish population in Europe.3 Despite the size of Ukraine’s Jewish population, academics and laypersons alike have for over two generations tended to talk about the Holocaust in the Soviet Union, Poland, Romania, or Hungary, but not about the Holocaust in Ukraine, which is the subject of this book. The reason for this traditional approach is evident. Unlike any of the aforementioned countries, Ukraine from the mid-thir teenth until the mid-twentieth century was but an ensemble of disparate territories partitioned among several neighboring pow ers. Ukrainian efforts to establish a state in these lands in the aftermath of the First World War were thwarted by internecine factionalism as well as Polish national aspirations and Soviet rev olutionary ambitions. Between the Polish-Soviet peace of 1920 and the Nazi-Soviet pact of 1939, the lands of modern Ukraine were split among Poland (eastern Galicia and western Volhynia), Czechoslovakia (Transcarpathia), Romania (northern Bukovina and southern Bessarabia), and the Soviet Union. -

National Historic Sites of Canada System Plan Will Provide Even Greater Opportunities for Canadians to Understand and Celebrate Our National Heritage

PROUDLY BRINGING YOU CANADA AT ITS BEST National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Parks Parcs Canada Canada 2 6 5 Identification of images on the front cover photo montage: 1 1. Lower Fort Garry 4 2. Inuksuk 3. Portia White 3 4. John McCrae 5. Jeanne Mance 6. Old Town Lunenburg © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, (2000) ISBN: 0-662-29189-1 Cat: R64-234/2000E Cette publication est aussi disponible en français www.parkscanada.pch.gc.ca National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Foreword Canadians take great pride in the people, places and events that shape our history and identify our country. We are inspired by the bravery of our soldiers at Normandy and moved by the words of John McCrae’s "In Flanders Fields." We are amazed at the vision of Louis-Joseph Papineau and Sir Wilfrid Laurier. We are enchanted by the paintings of Emily Carr and the writings of Lucy Maud Montgomery. We look back in awe at the wisdom of Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir George-Étienne Cartier. We are moved to tears of joy by the humour of Stephen Leacock and tears of gratitude for the courage of Tecumseh. We hold in high regard the determination of Emily Murphy and Rev. Josiah Henson to overcome obstacles which stood in the way of their dreams. We give thanks for the work of the Victorian Order of Nurses and those who organ- ized the Underground Railroad. We think of those who suffered and died at Grosse Île in the dream of reaching a new home.