Ambitions for Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Wednesday Volume 501 25 November 2009 No. 5 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Wednesday 25 November 2009 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2009 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 513 25 NOVEMBER 2009 514 my hon. Friend the Member for North Ayrshire and House of Commons Arran (Ms Clark). In a letter I received from Ofcom, the regulator states: Wednesday 25 November 2009 “Ofcom does not have the power to mandate ISPs”— internet service providers. Surely that power is overdue, because otherwise, many of my constituents, along with The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock those of my colleagues, will continue to receive a poor broadband service. PRAYERS Mr. Murphy: My hon. Friend makes some very important points about the decision-making powers and architecture [MR.SPEAKER in the Chair] that will ensure we achieve 90 per cent. broadband penetration. We are trying to ensure that the market provides most of that, and we expect that up to two thirds—60 to 70 per cent.—of homes will be able to Oral Answers to Questions access super-fast broadband through the market. However, the Government will have to do additional things, and my hon. Friend can make the case for giving Ofcom SCOTLAND additional powers; but, again, we are absolutely determined that no one be excluded for reasons of geography or income. -

Scottish Parliament Report

European Committee 3rd Report, 2002 Report on the Inquiry into the Future of Cohesion Policy and Structural Funds post 2006 SP Paper 618 £13.30 Session 1 (2002) Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body 2002. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to the Copyright Unit, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ Fax 01603 723000, which is administering the copyright on behalf of the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body. Produced and published in Scotland on behalf of the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body by The Stationery Office Ltd. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office is independent of and separate from the company now trading as The Stationery Office Ltd, which is responsible for printing and publishing Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body publications. European Committee 3rd Report, 2002 Report on the Inquiry into the Future of Cohesion Policy and Structural Funds post 2006 European Committee Remit and membership Remit: 1. The remit of the European Committee is to consider and report on- (a) proposals for European Communities legislation; (b) the implementation of European Communities legislation; and (c) any European Communities or European Union issue. 2. The Committee may refer matters to the Parliamentary Bureau or other committees where it considers it appropriate to do so. 3. The convener of the Committee shall not be the convener of any other committee whose remit is, in the opinion of the Parliamentary Bureau, relevant to that of the Committee. 4. The Parliamentary Bureau shall normally propose a person to be a member of the Committee only if he or she is a member of another committee whose remit is, in the opinion of the Parliamentary Bureau, relevant to that of the Committee. -

Scottish Parliament Annual Report 2012–13 Contents

Scottish Parliament Annual Report 2012–13 Contents Foreword from the Presiding Officer 3 Parliamentary business 5 Committees 11 International engagement 18 Engagement with the public 20 Click on the links in the page headers to access more information about the areas covered in this report. Cover photographs - clockwise from top left: Lewis Macdonald MSP and Richard Baker MSP in the Chamber Local Government and Regeneration Committee Education visit to the Parliament Special Delivery: The Letters of William Wallace exhibition Rural Affairs, Climate Change and Environment Committee Festival of Politics event Welfare Reform Committee witnesses Inside cover photographs - clockwise from top left: Health and Sport Committee witnesses Carers Parliament event The Deputy First Minister and First Minister The Presiding Officer at ArtBeat studios during Parliament Day Hawick Large Hadron Collider Roadshow Published in Edinburgh by APS Group Scotland © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body 2013 Information on the Scottish Parliament’s copyright policy can be found on the website - www.scottish.parliament.uk/copyright or by contacting public information on 0131 348 5000. ISBN 978-1-78351-356-7 SP Paper Number 350 Web Only Session 4 (2013) www.scottish.parliament.uk/PresidingOfficer Foreword from the Presiding Officer This annual report provides information on how the Scottish Parliament has fulfilled its role during the parliamentary year 11 May 2012 to 10 May 2013. This last year saw the introduction of reforms designed to make Parliament more agile and responsive through the most radical changes to our processes since the Parliament’s establishment in 1999. A new parliamentary sitting pattern was adopted, with the full Parliament now meeting on three days per week. -

DFID Annual Report 2008

House of Commons International Development Committee DFID Annual Report 2008 Second Report of Session 2008–09 Volume II Oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 10 February 2009 HC 220-II [Incorporating HC 945-i, -ii and -iii of Session 2007-08 Published on 19 February 2009 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 International Development Committee The International Development Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for International Development and its associated public bodies. Current membership Malcolm Bruce MP (Liberal Democrat, Gordon) (Chairman) John Battle MP (Labour, Leeds West) Hugh Bayley MP (Labour, City of York) John Bercow MP (Conservative, Buckingham) Richard Burden MP (Labour, Birmingham Northfield) Mr Stephen Crabb MP (Conservative, Preseli Pembrokeshire) Mr Mark Hendrick MP (Labour Co-op, Preston) Daniel Kawczynski MP (Conservative, Shrewsbury and Atcham) Jim Sheridan MP (Labour, Paisley and Renfrewshire North) Mr Marsha Singh MP (Labour, Bradford West) Andrew Stunell (Liberal Democrat, Hazel Grove) Ann McKechin (Labour, Glasgow North) and Sir Robert Smith (Liberal Democrat, West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine) were also members of the Committee during this inquiry. Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. -

Radical Nostalgia, Progressive Patriotism and Labour's 'English Problem'

Radical nostalgia, progressive patriotism and Labour©s ©English problem© Article (Accepted Version) Robinson, Emily (2016) Radical nostalgia, progressive patriotism and Labour's 'English problem'. Political Studies Review, 14 (3). pp. 378-387. ISSN 1478-9299 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/61679/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Author’s Post-Print Copy Radical nostalgia, progressive patriotism and Labour's 'English problem' Emily Robinson, University of Sussex ABSTRACT ‘Progressive patriots’ have long argued that Englishness can form the basis of a transformative political project, whether based on an historic tradition of resistance to state power or an open and cosmopolitan identity. -

Scottish Parliament Elections: 5 May 2011

Scottish Parliament Elections: 2011 RESEARCH PAPER 11/41 24 May 2011 The SNP gained an overall majority in the Scottish Parliament in the elections on 5 May 2011. The paper provides data on voting trends and electoral turnout for constituencies, electoral regions, and for Scotland as a whole. This paper is a companion volume to Library Research Papers 11/40 National Assembly for Wales Elections: 5 May 2011; 11/42, Northern Ireland Assembly Elections: 5 May 2011; 11/43, Local Elections 2011; and 11/44, Alternative Vote referendum 5 May 2011. Mark Sandford Recent Research Papers 11/28 Police Reform and Social Responsibility Bill: Committee 24.03.11 Stage Report 11/29 Economic Indicators, April 2011 05.04.11 11/30 Direct taxes: rates and allowances 2011/12 06.04.11 11/31 Health and Social Care Bill: Committee Stage Report 06.04.11 11/32 Localism Bill: Committee Stage Report 12.04.11 11/33 Unemployment by Constituency, April 2011 14.04.11 11/34 London Olympic Games and Paralympic Games (Amendment) Bill 21.04.11 [Bill 165 of 2010-12] 11/35 Economic Indicators, May 2011 03.05.11 11/36 Energy Bill [HL] [Bill 167 of 2010-12] 04.05.11 11/37 Education Bill: Committee Stage Report 05.05.11 11/38 Social Indicators 06.05.11 11/39 Legislation (Territorial Extent) Bill: Committee Stage Report 11.05.11 Research Paper 11/41 Contributing Authors: Mark Sandford Jeremy Hardacre This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. -

One Nation Economy

Labour’s Policy Review 1 ONE NATION ECONOMY Labour Party | One Nation Economy contentS Foreword by Ed Miliband and Ed Balls 5 Introduction by Jon Cruddas 7 Fair deficit reduction 9 Jobs for the future 13 One Nation banking 19 An energy market people can trust 23 Runaway rewards at the top… 29 …low pay and insecurity for everyone else 33 Building long-termism into the economy 39 Backing the forgotten 50% 43 Controlling social security spending – tackling the root causes 49 Immigration that works for Britain 53 3 Labour Party | One Nation Economy 4 Labour Party | One Nation Economy FOREWORD BY ED MILIBAND AND ED BALLS Britain needs to build an economy that works for all working people once again. For most of the twentieth century there was a vital link between the wealth of the country as a whole and the family finances of millions of hard-working families. As the country got better off, so did working people. A growing economy brought shared prosperity. And that meant that people who put in effort were rewarded, with good jobs, paying decent wages, and were able to make a better life for themselves. Millions of families bought a house, a car, even a second car, took holidays abroad, started their own business, looked forward to a stable pension in retirement and were confident that they could set their children up in life so they could enjoy a better life than themselves. That seems like a different world for millions of working families in Britain today. And that’s because that vital link between the overall wealth of the country and the family budget has been broken. -

Spice Briefing

MSPs BY CONSTITUENCY AND REGION Scottish SESSION 1 Parliament This Fact Sheet provides a list of all Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) who served during the first parliamentary session, Fact sheet 12 May 1999-31 March 2003, arranged alphabetically by the constituency or region that they represented. Each person in Scotland is represented by 8 MSPs – 1 constituency MSPs: Historical MSP and 7 regional MSPs. A region is a larger area which covers a Series number of constituencies. 30 March 2007 This Fact Sheet is divided into 2 parts. The first section, ‘MSPs by constituency’, lists the Scottish Parliament constituencies in alphabetical order with the MSP’s name, the party the MSP was elected to represent and the corresponding region. The second section, ‘MSPs by region’, lists the 8 political regions of Scotland in alphabetical order. It includes the name and party of the MSPs elected to represent each region. Abbreviations used: Con Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Green Scottish Green Party Lab Scottish Labour LD Scottish Liberal Democrats SNP Scottish National Party SSP Scottish Socialist Party 1 MSPs BY CONSTITUENCY: SESSION 1 Constituency MSP Region Aberdeen Central Lewis Macdonald (Lab) North East Scotland Aberdeen North Elaine Thomson (Lab) North East Scotland Aberdeen South Nicol Stephen (LD) North East Scotland Airdrie and Shotts Karen Whitefield (Lab) Central Scotland Angus Andrew Welsh (SNP) North East Scotland Argyll and Bute George Lyon (LD) Highlands & Islands Ayr John Scott (Con)1 South of Scotland Ayr Ian -

Written Answers

Thursday 6 October 2011 SCOTTISH EXECUTIVE Finance and Sustainable Growth Sandra White (Glasgow Kelvin) (Scottish National Party): To ask the Scottish Executive what progress it has made on the development of its cities strategy. (S4O-00266) Nicola Sturgeon: We are working to publish the strategy by the end of 2011 and all six cities are fully engaged in working collaboratively with Scottish Government to identify specific areas where a cities strategy can add most value. Health and Wellbeing Derek Mackay (Renfrewshire North and West) (Scottish National Party): To ask the Scottish Executive what progress has been made by NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde on the delivery of a family nurse partnership. (S4O-00262) Nicola Sturgeon: We are in discussion with NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde to identify the best place to deliver the Family Nurse Partnership programme. Alison Johnstone (Lothian) (Scottish Green Party): To ask the Scottish Executive what its position is on the World Health Organization report, Persistent Organic Pollutants: Impact on Child Health. (S4O-00263) Michael Matheson: The Scottish Government has noted this report, since its recommendations reinforce the existing health policies and initiatives being taken forward already across the Scottish Government and its agencies. Neil Bibby (West Scotland) (Scottish Labour): To ask the Scottish Executive what its position is on the role, value and potential of sport in Scottish society. (S4O-00264) Shona Robison: Sport has a significant contribution and can deliver a far reaching impact on our nation, economy, culture, international standing and reputation. This and helping to prolong life, improve physical strength and protect mental wellbeing is why this government is committed to maximising the benefits that can be delivered through sport. -

Z675928x Margaret Hodge Mp 06/10/2011 Z9080283 Lorely

Z675928X MARGARET HODGE MP 06/10/2011 Z9080283 LORELY BURT MP 08/10/2011 Z5702798 PAUL FARRELLY MP 09/10/2011 Z5651644 NORMAN LAMB 09/10/2011 Z236177X ROBERT HALFON MP 11/10/2011 Z2326282 MARCUS JONES MP 11/10/2011 Z2409343 CHARLOTTE LESLIE 12/10/2011 Z2415104 CATHERINE MCKINNELL 14/10/2011 Z2416602 STEPHEN MOSLEY 18/10/2011 Z5957328 JOAN RUDDOCK MP 18/10/2011 Z2375838 ROBIN WALKER MP 19/10/2011 Z1907445 ANNE MCINTOSH MP 20/10/2011 Z2408027 IAN LAVERY MP 21/10/2011 Z1951398 ROGER WILLIAMS 21/10/2011 Z7209413 ALISTAIR CARMICHAEL 24/10/2011 Z2423448 NIGEL MILLS MP 24/10/2011 Z2423360 BEN GUMMER MP 25/10/2011 Z2423633 MIKE WEATHERLEY MP 25/10/2011 Z5092044 GERAINT DAVIES MP 26/10/2011 Z2425526 KARL TURNER MP 27/10/2011 Z242877X DAVID MORRIS MP 28/10/2011 Z2414680 JAMES MORRIS MP 28/10/2011 Z2428399 PHILLIP LEE MP 31/10/2011 Z2429528 IAN MEARNS MP 31/10/2011 Z2329673 DR EILIDH WHITEFORD MP 31/10/2011 Z9252691 MADELEINE MOON MP 01/11/2011 Z2431014 GAVIN WILLIAMSON MP 01/11/2011 Z2414601 DAVID MOWAT MP 02/11/2011 Z2384782 CHRISTOPHER LESLIE MP 04/11/2011 Z7322798 ANDREW SLAUGHTER 05/11/2011 Z9265248 IAN AUSTIN MP 08/11/2011 Z2424608 AMBER RUDD MP 09/11/2011 Z241465X SIMON KIRBY MP 10/11/2011 Z2422243 PAUL MAYNARD MP 10/11/2011 Z2261940 TESSA MUNT MP 10/11/2011 Z5928278 VERNON RODNEY COAKER MP 11/11/2011 Z5402015 STEPHEN TIMMS MP 11/11/2011 Z1889879 BRIAN BINLEY MP 12/11/2011 Z5564713 ANDY BURNHAM MP 12/11/2011 Z4665783 EDWARD GARNIER QC MP 12/11/2011 Z907501X DANIEL KAWCZYNSKI MP 12/11/2011 Z728149X JOHN ROBERTSON MP 12/11/2011 Z5611939 CHRIS -

Current Msps by Party

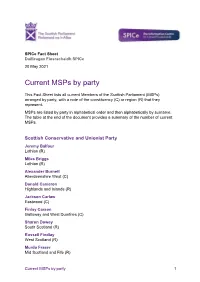

SPICe Fact Sheet Duilleagan Fiosrachaidh SPICe 20 May 2021 Current MSPs by party This Fact Sheet lists all current Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) arranged by party, with a note of the constituency (C) or region (R) that they represent. MSPs are listed by party in alphabetical order and then alphabetically by surname. The table at the end of the document provides a summary of the number of current MSPs. Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Jeremy Balfour Lothian (R) Miles Briggs Lothian (R) Alexander Burnett Aberdeenshire West (C) Donald Cameron Highlands and Islands (R) Jackson Carlaw Eastwood (C) Finlay Carson Galloway and West Dumfries (C) Sharon Dowey South Scotland (R) Russell Findlay West Scotland (R) Murdo Fraser Mid Scotland and Fife (R) Current MSPs by party 1 Meghan Gallacher Central Scotland (R) Maurice Golden North East Scotland (R) Pam Gosal West Scotland (R) Jamie Greene West Scotland (R) Sandesh Gulhane Glasgow (R) Jamie Halcro Johnston Highlands and Islands (R) Rachael Hamilton Ettrick, Roxburgh and Berwickshire (C) Craig Hoy South Scotland (R) Liam Kerr North East Scotland (R) Stephen Kerr Central Scotland (R) Dean Lockhart Mid Scotland and Fife (R) Douglas Lumsden North East Scotland (R) Edward Mountain Highlands and Islands (R) Oliver Mundell Dumfriesshire (C) Douglas Ross Highlands and Islands (R) Graham Simpson Central Scotland (R) Liz Smith Mid Scotland and Fife (R) Alexander Stewart Mid Scotland and Fife (R) Current MSPs by party 2 Sue Webber Lothian (R) Annie Wells Glasgow (R) Tess White North East -

Ministers, Law Officers and Ministerial Parliamentary Aides by Cabinet

MINISTERS, LAW OFFICERS AND Scottish MINISTERIAL PARLIAMENTARY AIDES BY Parliament CABINET: SESSION 1 Fact sheet This Fact sheet provides a list of all of the Scottish Ministers, Law Officers and Ministerial Parliamentary Aides during Session 1, from 12 May 1999 until the appointment of new Ministers in the second MSPs: Historical parliamentary session. Series Ministers and Law Officers continue to serve in post during 30 March 2007 dissolution. The first Session 2 cabinet was appointed on 21st May 2003. A Minister is a member of the government. The Scottish Executive is the government in Scotland for devolved matters and is responsible for formulating and implementing policy in these areas. The Scottish Executive is formed from the party or parties holding a majority of seats in the Parliament. During Session 1 the Scottish Executive consisted of a coalition of Labour and Liberal Democrat MSPs. The senior Ministers in the Scottish government are known as ‘members of the Scottish Executive’ or ‘the Scottish Ministers’ and together they form the Scottish ‘Cabinet’. They are assisted by junior Scottish Ministers. With the exception of the Scottish Law Officers, all Ministers must be MSPs. This fact sheet also provides a list of the Law Officers. The Scottish Law Officers listed advise the Scottish Executive on legal matters and represent its interests in court. The final section lists Ministerial Parliamentary Aides (MPAs). MPAs are MSPs appointed by the First Minister on the recommendation of Ministers whom they assist in discharging their duties. MPAs are unpaid and are not part of the Executive. Their role and the arrangements for their appointment are set out in paragraphs 4.6-4.13 of the Scottish Ministerial Code.