Scottish Parliament Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Report

EUROPEAN AND EXTERNAL RELATIONS COMMITTEE Tuesday 2 December 2003 (Afternoon) Session 2 £5.00 Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body 2003. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to the Licensing Division, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ Fax 01603 723000, which is administering the copyright on behalf of the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body. Produced and published in Scotland on behalf of the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body by The Stationery Office Ltd. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office is independent of and separate from the company now trading as The Stationery Office Ltd, which is responsible for printing and publishing Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body publications. CONTENTS Tuesday 2 December 2003 Col. FISHERIES (P RE-COUNCIL BRIEFING) ........................................................................................................ 222 SCOTTISH EXECUTIVE (SCRUTINY) ........................................................................................................... 246 CONVENER’S REPORT ............................................................................................................................ 251 INTERGOV ERNMENTAL CONFERENCE ........................................................................................................ 257 SIFT .................................................................................................................................................... 258 EUROPEAN AND -

Scottish Parliament Annual Report 2012–13 Contents

Scottish Parliament Annual Report 2012–13 Contents Foreword from the Presiding Officer 3 Parliamentary business 5 Committees 11 International engagement 18 Engagement with the public 20 Click on the links in the page headers to access more information about the areas covered in this report. Cover photographs - clockwise from top left: Lewis Macdonald MSP and Richard Baker MSP in the Chamber Local Government and Regeneration Committee Education visit to the Parliament Special Delivery: The Letters of William Wallace exhibition Rural Affairs, Climate Change and Environment Committee Festival of Politics event Welfare Reform Committee witnesses Inside cover photographs - clockwise from top left: Health and Sport Committee witnesses Carers Parliament event The Deputy First Minister and First Minister The Presiding Officer at ArtBeat studios during Parliament Day Hawick Large Hadron Collider Roadshow Published in Edinburgh by APS Group Scotland © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body 2013 Information on the Scottish Parliament’s copyright policy can be found on the website - www.scottish.parliament.uk/copyright or by contacting public information on 0131 348 5000. ISBN 978-1-78351-356-7 SP Paper Number 350 Web Only Session 4 (2013) www.scottish.parliament.uk/PresidingOfficer Foreword from the Presiding Officer This annual report provides information on how the Scottish Parliament has fulfilled its role during the parliamentary year 11 May 2012 to 10 May 2013. This last year saw the introduction of reforms designed to make Parliament more agile and responsive through the most radical changes to our processes since the Parliament’s establishment in 1999. A new parliamentary sitting pattern was adopted, with the full Parliament now meeting on three days per week. -

Stagecoach Group out in Front for 10-Year Tram Contract Responsible for Operating Tram Services on the New Lines to Oldham, Rochdale, Droylsden and Chorlton

AquaBus New alliance Meet the Sightseeing ready to forged for megabus.com tours' bumper set sail rail bid A-Team launch The newspaper of Stagecoach Group Issue 66 Spring 07 By Steven Stewart tagecoach Group has been Sselected as the preferred bidder to operate and maintain the Manchester Metrolink tram Metrolink bid network. The announcement from Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive (GMPTE) will see Stagecoach Metrolink taking over the 37km system and the associated infrastructure. The contract will run for 10 years and is expected to begin within the next three months. right on track It will include managing a number of special projects sponsored by GMPTE to improve the trams and infrastructure to benefit passengers. Stagecoach Metrolink will also be Stagecoach Group out in front for 10-year tram contract responsible for operating tram services on the new lines to Oldham, Rochdale, Droylsden and Chorlton. Nearly 20 million passengers travel every year on the network, which generates an annual turnover of around £22million. ”We will build on our operational expertise to deliver a first-class service to passengers in Manchester.” Ian Dobbs Stagecoach already operates Supertram, a 29km tram system in Sheffield, incorpo- rating three routes in the city. Ian Dobbs, Chief Executive of Stagecoach Group’s Rail Division, said: “We are delighted to have been selected as preferred bidder to run Manchester’s Metrolink network, one of the UK’s premier light rail systems. “Stagecoach operates the tram system in Sheffield, where we are now carrying a record 13 million passengers a year, and we will build on our operational expertise to deliver a first-class service to passengers in Growing places: Plans are in place to tempt more people on to the tram in Manchester. -

Fact Sheet Msps by Party Session 4 29 March 2016 Msps: Historical Series

The Scottish Parliament and Scottish Parliament I nfor mation C entre l ogo Scottish Parliament Fact sheet MSPs by Party Session 4 29 March 2016 MSPs: Historical Series This Fact sheet provides a cumulative list of all Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) who served during session 4, arranged by party. It also includes the Independent MSPs. The MSPs are listed in alphabetical order, by the party that they were elected to represent, with the party with most MSPs listed first. Statistical information about the number of MSPs in each party in Session 4 can be found on the State of the Parties Session 4 fact sheet. Scottish National Party MSP Constituency (C) or Region (R) Brian Adam 1 Aberdeen Donside (C) George Adam Paisley (C) Clare Adamson Central Scotland (R) Alasdair Allan Na h-Eileanan an lar (C) Christian Allard2 North East Scotland (R) Colin Beattie Midlothian North and Musselburgh (C) Marco Biagi Edinburgh Central (C) Chic Brodie South of Scotland (R) Keith Brown Clackmannanshire & Dunblane (C) Margaret Burgess Cunninghame South (C) Aileen Campbell Clydesdale (C) Roderick Campbell North East Fife (C) Willie Coffey Kilmarnock and Irvine Valley (C) Angela Constance Almond Valley (C) Bruce Crawford Stirling (C) Roseanna Cunningham Perthshire South and Kinross-shire (C) Graeme Dey Angus South (C) Nigel Don Angus North and Mearns (C) Bob Doris Glasgow (R) James Dornan Glasgow Cathcart (C) Jim Eadie Edinburgh Southern (C) Annabelle Ewing Mid Scotland and Fife (R) Fergus Ewing Inverness and Nairn (C) Linda Fabiani East Kilbride (C) Joe FitzPatrick Dundee City West (C) Kenneth Gibson Cunninghame North (C) Rob Gibson Caithness, Sutherland and Ross (C) Midlothian South, Tweeddale and Christine Grahame Lauderdale (C) 1 Brian Adam died on 25 April 2013. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

![SPOKES Leaflet 86 Late 2003 and Richard Lochhead [SNP]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0410/spokes-leaflet-86-late-2003-and-richard-lochhead-snp-370410.webp)

SPOKES Leaflet 86 Late 2003 and Richard Lochhead [SNP]

POLITICIANS WE LIKE!! Following the Scottish Parliament election the Cross Party ESSENTIAL CONTACTS Cycle Group re-formed. Mark Ruskell [Green] is new Cycle training: 01505,614302 [email protected]. convener, with vice-conveners Bristow Muldoon [Uib] Traveline Scotland: rail, bus, ferry info [lo include cycle aspects SPOKES Leaflet 86 Late 2003 and Richard Lochhead [SNP]. Meetings are open to the and eyclemap lealleis?] 0870,608,2508 tvww.lraveline.org.uk. public. Details: [email protected]. Potholes, glass on cycleroutes, broken lights, etc anywhere SPOKES, The Lothian Cycle Campaign, St Martins Church, 232 Dairy Road, Edinburgh EHll 2JG ® 0131.313,2114 hIlD;//www,spokes,or£,uk/ /This is a mail address and answerphone - SPOKES is a voluntary organisation mtk nasiaffj Some 15 MSPs [below] signed up for Bike to Work day in Lothian [including Edinburgh], or Falkirk District: and/or joined the Bike Breakfast MSP ride 118.5.03.phoio]. [Use number oti nearesi lamp-posi lo report exact location]. Phone Lab: Sarah Boyack.KcnMcIniosh, PaulintMcNcill, B-Muldoiin 0800.232.123; Or see www.adinburfih.^ov.uk - Iransporl -Clarence. BIKE FUNDS THREAT Grn: Mark Ballard, Cliris Ballance, Robin Harper, Mark Ruskell Bad glass/dumping [Ed only]: Rapid Response 0808.100.3365 Despite two welcome government announcements which SNP: Richard Lochhead, Jim Mather SS/"; Rosie Kane Smoky commercial vehicles: 01506.445216. will assist smaller cycle projects, overall cycle project LibD: Tavish Scotl, Nora Radcliffe Con: Brian Monlcilh Drink-driving, speeding, driving whilst disqualified, and spending is set to fall drastically in less than two years. other road crime: Freephone Crimestoppers 0800.555.111. -

Spice Briefing

MSPs BY CONSTITUENCY AND REGION Scottish SESSION 1 Parliament This Fact Sheet provides a list of all Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) who served during the first parliamentary session, Fact sheet 12 May 1999-31 March 2003, arranged alphabetically by the constituency or region that they represented. Each person in Scotland is represented by 8 MSPs – 1 constituency MSPs: Historical MSP and 7 regional MSPs. A region is a larger area which covers a Series number of constituencies. 30 March 2007 This Fact Sheet is divided into 2 parts. The first section, ‘MSPs by constituency’, lists the Scottish Parliament constituencies in alphabetical order with the MSP’s name, the party the MSP was elected to represent and the corresponding region. The second section, ‘MSPs by region’, lists the 8 political regions of Scotland in alphabetical order. It includes the name and party of the MSPs elected to represent each region. Abbreviations used: Con Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Green Scottish Green Party Lab Scottish Labour LD Scottish Liberal Democrats SNP Scottish National Party SSP Scottish Socialist Party 1 MSPs BY CONSTITUENCY: SESSION 1 Constituency MSP Region Aberdeen Central Lewis Macdonald (Lab) North East Scotland Aberdeen North Elaine Thomson (Lab) North East Scotland Aberdeen South Nicol Stephen (LD) North East Scotland Airdrie and Shotts Karen Whitefield (Lab) Central Scotland Angus Andrew Welsh (SNP) North East Scotland Argyll and Bute George Lyon (LD) Highlands & Islands Ayr John Scott (Con)1 South of Scotland Ayr Ian -

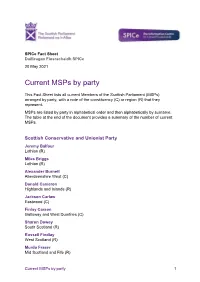

Current Msps by Party

SPICe Fact Sheet Duilleagan Fiosrachaidh SPICe 20 May 2021 Current MSPs by party This Fact Sheet lists all current Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) arranged by party, with a note of the constituency (C) or region (R) that they represent. MSPs are listed by party in alphabetical order and then alphabetically by surname. The table at the end of the document provides a summary of the number of current MSPs. Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Jeremy Balfour Lothian (R) Miles Briggs Lothian (R) Alexander Burnett Aberdeenshire West (C) Donald Cameron Highlands and Islands (R) Jackson Carlaw Eastwood (C) Finlay Carson Galloway and West Dumfries (C) Sharon Dowey South Scotland (R) Russell Findlay West Scotland (R) Murdo Fraser Mid Scotland and Fife (R) Current MSPs by party 1 Meghan Gallacher Central Scotland (R) Maurice Golden North East Scotland (R) Pam Gosal West Scotland (R) Jamie Greene West Scotland (R) Sandesh Gulhane Glasgow (R) Jamie Halcro Johnston Highlands and Islands (R) Rachael Hamilton Ettrick, Roxburgh and Berwickshire (C) Craig Hoy South Scotland (R) Liam Kerr North East Scotland (R) Stephen Kerr Central Scotland (R) Dean Lockhart Mid Scotland and Fife (R) Douglas Lumsden North East Scotland (R) Edward Mountain Highlands and Islands (R) Oliver Mundell Dumfriesshire (C) Douglas Ross Highlands and Islands (R) Graham Simpson Central Scotland (R) Liz Smith Mid Scotland and Fife (R) Alexander Stewart Mid Scotland and Fife (R) Current MSPs by party 2 Sue Webber Lothian (R) Annie Wells Glasgow (R) Tess White North East -

Ministers, Law Officers and Ministerial Parliamentary Aides by Cabinet

MINISTERS, LAW OFFICERS AND Scottish MINISTERIAL PARLIAMENTARY AIDES BY Parliament CABINET: SESSION 1 Fact sheet This Fact sheet provides a list of all of the Scottish Ministers, Law Officers and Ministerial Parliamentary Aides during Session 1, from 12 May 1999 until the appointment of new Ministers in the second MSPs: Historical parliamentary session. Series Ministers and Law Officers continue to serve in post during 30 March 2007 dissolution. The first Session 2 cabinet was appointed on 21st May 2003. A Minister is a member of the government. The Scottish Executive is the government in Scotland for devolved matters and is responsible for formulating and implementing policy in these areas. The Scottish Executive is formed from the party or parties holding a majority of seats in the Parliament. During Session 1 the Scottish Executive consisted of a coalition of Labour and Liberal Democrat MSPs. The senior Ministers in the Scottish government are known as ‘members of the Scottish Executive’ or ‘the Scottish Ministers’ and together they form the Scottish ‘Cabinet’. They are assisted by junior Scottish Ministers. With the exception of the Scottish Law Officers, all Ministers must be MSPs. This fact sheet also provides a list of the Law Officers. The Scottish Law Officers listed advise the Scottish Executive on legal matters and represent its interests in court. The final section lists Ministerial Parliamentary Aides (MPAs). MPAs are MSPs appointed by the First Minister on the recommendation of Ministers whom they assist in discharging their duties. MPAs are unpaid and are not part of the Executive. Their role and the arrangements for their appointment are set out in paragraphs 4.6-4.13 of the Scottish Ministerial Code. -

Summary of the 27Th Plenary Session, October 2003

BRITISH-IRISH INTER- PARLIAMENTARY BODY COMHLACHT IDIR- PHARLAIMINTEACH NA BREATAINE AGUS NA hÉIREANN _________________________ TWENTY-SEVENTH PLENARY CONFERENCE 20 and 21 OCTOBER 2003 Hanbury Manor Hotel & Country Club, Ware, Hertfordshire _______________________ OFFICIAL REPORT (Final Revised Edition) (Produced by the British-Irish Parliamentary Reporting Association) Any queries should be sent to: The Editor The British-Irish Parliamentary Reporting Association Room 248 Parliament Buildings Stormont Belfast BT4 3XX Tel: 028 90521135 e-mail [email protected] IN ATTENDANCE Co-Chairmen Mr Brendan Smith TD Mr David Winnick MP Members and Associate Members Mr Harry Barnes MP Mr Séamus Kirk TD Senator Paul Bradford Senator Terry Le Sueur Mr Johnny Brady TD Dr Dai Lloyd AM Rt Hon the Lord Brooke Rt Hon Andrew Mackay MP of Sutton Mandeville CH Mr Andrew Mackinlay MP Mr Alistair Carmichael MP Dr John Marek AM Senator Paul Coughlan Mr Michael Mates MP Dr Jerry Cowley TD Rt Hon Sir Brian Mawhinney MP Mr Seymour Crawford TD Mr Kevin McNamara MP Dr Jimmy Devins TD Mr David Melding AM The Lord Dubs Senator Paschal Mooney Ms Helen Eadie MSP Mr Arthur Morgan TD Mr John Ellis TD Mr Alasdair Morrison MSP Mr Jeff Ennis MP Senator Francie O’Brien Ms Margaret Ewing MSP Mr William O’Brien MP Mr Paul Flynn MP Mr Donald J Gelling CBE MLC Ms Liz O’Donnell TD Mr Mike German AM Mr Ned O’Keeffe TD Mr Jim Glennon TD Mr Jim O’Keeffe TD The Lord Glentoran CBE DL Senator Ann Ormonde Mr Dominic Grieve MP Mr Séamus Pattison TD Mr John Griffiths AM Senator -

Constitutional Convention for Giving Firm Shape to That Will

We Commend ..... This report is about practical intent. It says: "Here is what we are going to do," not "here is what we would like". Those who seek inspirational home rule rhetoric are respectfully directed elsewhere, including to the Convention's own previous publications. We have moved on. We regard the argument in principle as compelling. The longing of the people of Scotland for their own Parliament rings clear and true every time opinion is sounded. We believe that the momentum for change is now too great to deny; and that a Scottish Parliament will soon be meeting for the first time in nearly three centuries. What has been missing has been a practical scheme for bringing the Parliament into existence, and a hard-headed assessment of what it will be able to achieve. That is the gap which this report fills. This report shows that the Parliament can work, and it shows how. In doing so, it answers opponents who have tried to portray a Scottish Parliament as a pipe- dream, a fantasy which the Scots, unlike other peoples around the world, somehow cannot turn into reality. The Convention has a diverse membership, as diverse as we could make it. Diversity and unanimity are not natural companions. It is the instinct of political parties to disagree with one another, and the instinct of civic groups like the churches, the trade unions and others to be impatient with the preoccupations of politicians. This has meant that a lot of time and effort has been required to arrive at the proposals in this document. -

Msps Not Standing Or Not Returned in the 2003

SESSION 1 MSPS NOT STANDING OR NOT Scottish RETURNED IN THE 2003 ELECTION Parliament Fact sheet A number of MSPs did not return to the Scottish Parliament in Session 2. They either did not stand for re-election or they stood as a candidate but were not re-elected. MSPs: Historical This fact sheets is divided into two sections. The first section lists Series those MSPs who stood for re-election but failed to win a seat. The second section lists those MSPs who were serving at the end of the 25 October 2005 first parliamentary session (31 March 2003) but chose not to stand for re-election. Abbreviations used: Con Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Ind Independent Lab Scottish Labour LD Scottish Liberal Democrats SNP Scottish National Party 1 MSPs that stood for re-election but failed to win a seat Brian Fitzpatrick Lab Strathkelvin & Bearsden Kenny Gibson SNP Glasgow Rhoda Grant Lab Highlands & Islands Iain Gray Lab Edinburgh Pentlands Keith Harding Con Mid Scotland & Fife John McAllion Lab Dundee East Irene McGugan SNP North East Scotland Lyndsay McIntosh Con Central Scotland Angus Mackay Lab Edinburgh South Fiona McLeod SNP West of Scotland Gil Paterson SNP Central Scotland Lloyd Quinan SNP West of Scotland Michael Russell SNP South of Scotland Dr Richard Simpson Lab Ochil Elaine Thomson Lab Aberdeen North Andrew Wilson SNP Central Scotland MSPs that did not stand for re-election Name Party Constituency or Region Colin Campbell SNP West of Scotland Dorothy-Grace Elder Ind Glasgow Dr Winnie Ewing SNP Highlands & Islands Duncan Hamilton SNP Highlands & Islands Ian Jenkins LD Tweeddale, Ettrick & Lauderdale Rt Hon Henry McLeish Lab Central Fife Rt Hon Sir David Steel KBE LD Lothians Kay Ullrich SNP West of Scotland Ben Wallace Con North East Scotland John Young OBE Con West of Scotland Scottish Parliament Fact sheet 2 Contacting the Public Information Service For more information you can visit our website at http://www.scottish.parliament.uk or contact the Public Information Service.