The Great Romanian Composer and Master of the Violin, George Enescu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Romanian Music for Unaccompanied

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KU ScholarWorks CONTEMPORARY ROMANIAN MUSIC FOR UNACCOMPANIED CLARINET BY 2009 Cosmin Teodor Hărşian Submitted to the graduate program in the Department of Music and Dance and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________ Chairperson Committee Members ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ Date defended 04. 21. 2009 The Document Committee for Cosmin Teodor Hărşian certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: CONTEMPORARY ROMANIAN MUSIC FOR UNACCOMPANIED CLARINET Committee: ________________________ Chairperson ________________________ Advisor Date approved 04. 21. 2009 ii ABSTRACT Hărșian, Cosmin Teodor, Contemporary Romanian Music for Unaccompanied Clarinet. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2009. Romanian music during the second half of the twentieth century was influenced by the socio-politic environment. During the Communist era, composers struggled among the official ideology, synchronizing with Western compositional trends of the time, and following their own natural style. With the appearance of great instrumentalists like clarinetist Aurelian Octav Popa, composers began writing valuable works that increased the quality and the quantity of the repertoire for this instrument. Works written for clarinet during the second half of the twentieth century represent a wide variety of styles, mixing elements from Western traditions with local elements of concert and folk music. While the four works discussed in this document are demanding upon one’s interpretative abilities and technically challenging, they are also musically rewarding. iii I wish to thank Ioana Hărșian, Voicu Hărșian, Roxana Oberșterescu, Ilie Oberșterescu and Michele Abbott for their patience and support. -

Rookh Quartet

Rookh Quartet Friday 29th January 2021, 1200 Programme Jamie Keesecker The Impetuous Winds Violeta Dinescu Abendandacht Drew Hammond Soliloquy (world premiere) Elizabeth Raum Quartet for Four Horns I. Allegretto con brio II. Andante con moto III. Scherzo IV. Echoes Alisson Kruusmaa Songs of a Black Butterfly Michael Kallstrom Head Banger Jane Stanley the evolution of Lalla Rookh* * This piece won’t be performed on Friday, but will be added to the programme following the initial YouTube livestream and will be available on our YouTube cannel together with the rest of the programme until 28th February. Q&A with Andy Saunders from Rookh Quartet and composers Jane Stanley and Drew Hammond after the performance Programme notes Jamie Keesecker: The Impetuous Winds (2008) The Impetuous Winds was written in 2008 for a composition workshop with visiting horn quartet Quadre, whilst horn player Jamie Keesecker was studying for his Masters in composition at the University of Oregon. Quadre were struck by the drama and excitement in the work, and took it into their repertoire, including it on their album ‘Our Time’. The whole range of the instrument is covered – almost 4 octaves – and there is a vast array of colour and contrast in the piece. The punchy opening uses the quartet as a mini-big band at times, with rhythmic drive and thick, luscious harmonies. The central section of the work has a long melodic line, which never quite goes in the expected direction, and there are echoes of Mahler’s horn writing in the duet that sits over a muted figure from two of the players. -

Nachhall Entspricht Mit Ausdeutungen Wie: Nachwirkend, Nachhaltig, Nicht Gleich Verklingend Dem Anliegen Des Buches Und Der Reihe Komponistinnen Und Ihr Werk

Christel Nies Der fünfte Band der Reihe Komponistinnen und ihr Werk doku- mentiert für die Jahre 2011 bis 2016 einundzwanzig Konzerte und Veranstaltungen mit Werkbeschreibungen, reichem Bildmaterial und den Biografien von 38 Komponistinnen. Sieben Komponistinnen beantworten Fragen zum Thema Komponistinnen und ihre Werke heute. Olga Neuwirth gibt in einem Interview mit Stefan Drees Auskunft über ihre Er- fahrungen als Komponistin im heutigen Musikleben. Freia Hoffmann (Sofie Drinker Institut), Susanne Rode- Breymann Christel Nies (FMG Hochschule für Musik, Theater und Medien, Han- nover) und Frank Kämpfer (Deutschlandfunk) spiegeln in ihren Beiträgen ein Symposium mit dem Titel Chancengleich- heit für Komponistinnen, Annäherung auf unterschiedlichen Wegen, das im Juli 2015 in Kassel stattfand. Christel Nies berichtet unter dem Titel Komponistinnen und ihr Werk, eine unendliche Geschichte von Entdeckungen und Aufführungen über ihre ersten Begegnungen mit dem Thema Frau und Musik, den darauf folgenden Aktivitäten und über Erfolge und Erfahrungen in 25 Jahren dieser „anderen Konzertreihe“. Der Buchtitel Nachhall entspricht mit Ausdeutungen wie: nachwirkend, nachhaltig, nicht gleich verklingend dem Anliegen des Buches und der Reihe Komponistinnen und ihr Werk. Nachhall Komponistinnen und ihr Werk V ISBN 978-3-7376-0238-9 ISBN 978-3-7376-0238-9 Komponistinnen und ihr Werk V 9 783737 602389 Christel Nies Nachhall Komponistinnen und ihr Werk V 1 2 Christel Nies Nachhall Komponistinnen und ihr Werk V kassel university kassel university press · Kassel press 3 Komponistinnen und ihr Werk V Eine Dokumentation der Veranstaltungsreihe 2011 bis 2016 Gefördert vom Hessischen Ministerium für Wissenschaft und Kunst Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. -

Pioneering Conductor Odaline De La Martinez Co-Curates Trailblazing Juilliard Focus Festival Acknowledging Early 20Th-Century Women Composers

Pioneering conductor Odaline de la Martinez co-curates trailblazing Juilliard Focus Festival acknowledging early 20th-century women composers Marking the centenary of women’s suffrage in the USA Friday 24 January – Friday 31 January Trailblazers – Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Peter Jay Sharp Theater & Alice Tully Hall Lincoln Center, New York Featuring music by 32 women composers from 15 countries on five continents “The exact worth of my music will probably not be known till nought remains of the writer but sexless dots and lines on ruled paper.” Ethel Smyth (1858-1944) Highlighting the pioneering writing of 20th-century women composers, composer- conductor Odaline de la Martinez co-curates Trailblazers — Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century – a Festival she leads alongside Festival Founder Joel Sachs. The Juilliard Focus 2020 Festival celebrates the centenary of women’s suffrage in the USA, with the Nineteenth Amendment first giving women the vote in 1920. Under co-curator Martinez, the Festival will this year advocate expressly on behalf of historical women composers to overcome the magnified problems they faced in establishing themselves as professional composers in the twentieth century and paving the way for those who followed. Inadequate archives mean many have been almost entirely neglected following their deaths; others, such as Rebecca Clarke (1886-1979), gave up composing upon marriage: “There’s nothing in the world more thrilling, or practically nothing. But you can’t do it – at least I can’t, maybe that’s where a woman’s different – unless it’s the first thing I think of every morning when I wake and the last thing I think of every night before I got to sleep.” – Rebecca Clarke Decades after composition, many pieces will be given American or New York premieres and performed for the first time in the young Juilliard performers’ lifetimes. -

Darmstadt Summer Course 14 – 28 July 2018

DARMSTADT SUMMER COURSE 14 – 28 JULY 2018 PREFACE 128 – 133 GREETINGS 134 – 135 COURSES 136 – 143 OPEN SPACE 144 – 145 AWARDS 146 – 147 DISCOURSE 148 – 151 DEFRAGMENTATION 152 – 165 FESTIVAL 166 – 235 TEXTS 236 – 247 TICKETS 248 For credits and imprint, please see the German part. For more information on the events, please see the daily programs or visit darmstaedter-ferienkurse.de CONTENTS A TEMPORARY This “something” is difficult to pin down, let alone plan, but can perhaps be hinted at in what we see as our central COMMUNITY concern: to form a temporary community, to try to bring together a great variety of people with the most varied Dr. Thomas Schäfer, Director of the International Music Institute Darmstadt (IMD) and Artistic Director of the Darmstadt Summer Course backgrounds and different types of prior knowledge, skills, expectations, experience and wishes for a very limited, yet Tradition has it that Plato bought the olive grove Akademos also very intense space of time. We hope to foster mutual around 387 BC and made it the first “philosophical garden”, understanding at the same time as inviting people to engage a place to hold a discussion forum for his many pupils. in vigorous debate. We are keener than ever to pursue a Intuitively, one imagines such a philosophical garden as discourse with an international community and discuss the follows: scholars and pupils, experts and interested parties, music and art of our time. We see mutual courtesy and fair connoisseurs and enthusiasts, universalists and specialists behavior towards one another as important, even fundamental come together in a particular place for a particular length preconditions for truly imbuing the spirit of such a temporary of time to exchange views, learn from one another, live and community with the necessary positive energy. -

Oldenburger Beiträge Zur Geschlechterforschung Band 12

Oldenburger Beiträge zur Geschlechterforschung Band 12 Die Schriftenreihe „Oldenburger Beiträge zur Geschlechterforschung“ wird seit September 2004 vom Zentrum für interdisziplinäre Frauen- und Geschlechterforschung an der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg (ZFG) herausgegeben. In variablen Abständen erschei- nen Bände von Wissenschaftlerinnen und Wissenschaftlern aus dem Kreis des ZFG zu aktuellen Fragestellungen, neueren Untersuchungen und innovativen wissenschaftlichen Projekten der Frauen- und Ge- schlechterforschung. Vor allem für Nachwuchswissenschaftlerinnen und -wissenschaftler bietet die Schriftenreihe die Möglichkeit, Projekt- berichte, Diplomarbeiten oder Dissertationen zu veröffentlichen. Herausgegeben vom Zentrum für interdisziplinäre Frauen- und Geschlechterforschung an der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg (ZFG) Musik und Emanzipation Festschrift für Freia Hoffmann zum 65. Geburtstag Herausgegeben von Marion Gerards und Rebecca Grotjahn BIS-Verlag der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg Gedruckt mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Mariann Steegmann Founda- tion Zürich sowie des Zentrums für interdisziplinäre Frauen- und Ge- schlechterforschung an der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg Oldenburg, 2010 Verlag / Druck / Vertrieb BIS-Verlag der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg Postfach 2541 26015 Oldenburg E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.bis-verlag.de ISBN 978-3-8142-2196-0 Inhalt Grußwort für Freia Hoffmann zum 65. Geburtstag aus dem Zentrum für interdisziplinäre Frauen- und Geschlechterforschung an der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg 9 Musik und Emanzipation Freia Hoffmann zum 65. Geburtstag 11 Geschlechterpolaritäten in der Musik Birgit Kiupel Die unbekannte Komponistin 20 Andreas Kisters Singt da ein Mann oder eine Frau? Anmerkungen zur Stimme in der mediterranen Volksmusik 23 Kadja Grönke Über das Werk zur Person. Čajkovskijs Romanzen op. 73 33 Fred Ritzel Über die (vielleicht) populärste Melodie einer Komponistin im 20. -

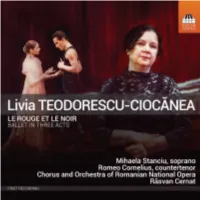

TOCC0595DIGIBKLT.Pdf

LIVIA TEODORESCU-CIOCĂNEA Le rouge et le noir 1 Prologue – 5:44 Act One 9:30 Scene I: A Small Town called Verrières 2 Soldiers’ March 1:38 Scene II: A Father and a Son 3 The Quarrel 1:57 Scene III: The Church 4 The Church 5:55 Act Two 26:35 Scene I: The Mayor’s House 5 The Meeting – 5:37 6 The Mayor's House (Passacaglia) 6:32 Scene II: Vergy 7 Vergy – Love Duet 8:19 Scene III: Besançon 8 The Seminary at Besançon 6:07 Act Three 23:42 Scene I: The High Aristocracy in Paris 9 The Ball 5:11 10 Seduction 3:18 11 Alone 3:09 Scene II: The Game of Letters 12 Korasoff 1:44 13 Passion Tango 3:17 Scene III: The Revenge 14 The Scandal 1:30 15 The Letter 0:46 16 The Bells – Carillon 4:47 2 Epilogue 10:05 17 The Prison– 3:03 18 The Judgement 0:58 19 Last Meeting– 2:51 20 The Execution– 1:40 21 The Death of Madame de Rênal 1:33 Mihaela Stanciu, soprano 19 TT 75:38 Romeo Cornelius, countertenor 8 Chorus (male voices) 8 and Orchestra of Romanian National Opera Luminiţa Elefteriu, concert-master Vasile Corjos, assistant choral conductor Răsvan Cernat, conductor FIRST RECORDING 3 LIVIA TEODORESCU-CIOCĂNEA: A BIOGRAPHICAL OUTLINE by Joel Crotty Livia Teodorescu-Ciocănea was born in Galaţi, a town in eastern Romania, on 4 February 1959. She studied piano at the Music and Arts College in Galaţi between 1965 and 1977, where one of her piano teachers was Charlotte Marcovici, who had studied in Vienna in the 1940s. -

Schriftenreihe Des Sophie Drinker Instituts

Schriftenreihe des Sophie Drinker Instituts Herausgegeben von Freia Hoffmann Michaela Krucsay Zwischen Aufklärung und barocker Prachtentfaltung Anna Bon di Venezia und ihre Familie von „Operisten“ Die Publikation wurde mit Mitteln des Landes Steiermark, Referat Wissenschaft und Forschung, gefördert. Oldenburg, 2015 Verlag/Druck/Vertrieb BIS-Verlag der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg Postfach 2541 26015 Oldenburg E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.bis-verlag.de ISBN 978-3-8142-2320-9 Meinen Großeltern Friederike Sofie und Alois Dreschnig sowie Andreas Krucsay in Liebe und Dankbarkeit Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorworte und Danksagung 9 Einleitung 13 1 Politische und soziale Rahmenbedingungen kulturellen Handelns für Frauen im Europa zur Zeit der Aufklärung und des frühen Bürgertums 17 1.1 Ideale weiblicher Bildung 21 1.2 Die Frau als Musikerin 24 2 Reisewege zwischen Musik und Bildender Kunst. Zu den Wirkungsstätten des Operisten-Ehepaars Bon 27 2.1 Kaiserliche Spektakel: Die italienischen Künstler am russischen Zarenhof 27 2.2 Die Opera buffa und Friedrich II. Dresden, Potsdam und Berlin 39 2.3 La cittella ingannata. Antwerpen 1752 42 2.4 Vom Reichstag zu Regensburg und einstürzenden Bretterbuden 44 3 Anna Bon di Venezia 51 3.1 Geburt in Bologna 51 3.2 Zur Aufnahme Anna Bons am Ospedale della Pietà 56 3.2.1 Kultur/Politik. Die Bedeutung des Ospedale della Pietà innerhalb der venezianischen ospedali 61 3.2.2 Inservienti della musica: Ausbildung und Organisation am Ospedale 70 3.2.3 Exkurs I: Maddalena Laura Lombardini Sirmen und Regina Strinasacchi- Schlick. Fallbeispiele prominenter Zeitgenossinnen 78 3.2.4 Exkurs II: Zur Rezeption der venezianischen ospedali in Literatur und Film 81 3.3 Wilhelmines „Musenhof“. -

Poppy Fields Câmpuri De Maci

Livia Teodorescu-Ciocănea Poppy Fields Câmpuri de maci Oratorio in memory of the soldiers who died during the First World War Poppy Fields Câmpuri de maci Oratorio in memory of the soldiers who died during the First World War for Mezzo-Soprano (ossia Soprano Dramatico), Tenor, Baritone, mixt choir and full orchestra Parts 1. Big Ben Eleven - Declaration of War (Baritone, choir and orchestra) 2. In Flanders Fields (Tenor, choir and orchestra) 3. "Români!" - Proclamația către țară a regelui Ferdinand ("Romanians" - King Ferdinand's proclamation to the Romanian people) (Baritone and orchestra) 4. În vârful Carpaților (On top of the Carpathians) (Tenor, choir and orchestra) 5. Rugăciunea Reginei Maria pentru cei căzuți (Prayer of Queen Marie for the Dead) (Mezzo-Soprano and orchestra) Biografie Muzica are putere nelimitată. A compune muzică înseamnă a împărtăși imaginația, inteligența și sentimentele tale. Ceea ce rezultă ar trebui să fie mai mult decât ți-ai imaginat inițial și dincolo de propria înțelegere. Misterul intangibil al muzicii tale va crește odată cu sensibilitatea, imaginația și așteptările fiecărui ascultător. Livia Teodorescu-Ciocănea Livia Teodorescu-Ciocănea este o compozitoare și pianistă concertistă română, profesor universitar doctor la Universitatea Națională de Muzică București, Departamentul de Compoziție, unde predă compoziție, stilistică și poetică, forme și analize muzicale. Numeroasele sale compoziții și înregistrări sunt apreciate internațional pentru viziunea lor puternică, impactul emoțional și rafinamentele timbrale remarcabile. O serie de lucrări muzicologice (cărți și capitole de carte) au fost publicate în țară, în timp ce câteva dintre articolele sale recenzate au fost acceptate în jurnale muzicologice internaționale de vârf. În 2008 a câștigat un grant internațional Endeavour Award – Postdoctoral Research Fellowship (2008) - finanțat de guvernul australian și efectuat la Universitatea Monash. -

Associate Professor Livia Teodorescu-Ciocanea

ADJUNCT ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR Professor Livia Teodorescu-Ciocănea 1 Professor Livia Teodorescu-Ciocănea, PhD, Habil. Composer, concert pianist Current Academic positions: Professor, National University of Music Bucharest, Romania Adjunct Associate Professor (Research), Sir Zelman Cowen School of Music, Monash University Contact: [email protected] Research Areas: • Timbre, Spectrum, advanced techniques for instruments (which I call hypertimbralism), always in connection with strong and articulate form and structure. • Orchestral composite timbre evaluation, considering the changing position of the spectral centroid (midpoint of the spectral energy) in connection with intensity levels. • Spectral analysis, spectral listening types (holistic listening and analytical listening), evaluation of tonalness, harmonicity, inharmonicity. • Byzantine music. • operatic music, both classical and modern. http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com.ezproxy.lib.monash.edu.au/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/97 81561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0002286779?rskey=37uONJ&result=1 https://www.facebook.com/LiviaTeodorescuCiocanea/ https://toccataclassics.com/product/livia-teodorescu-ciocanea-piano/ https://repertoire-explorer.musikmph.de/en/product/teodorescu-ciocanea-livia/ BIOGRAPHY ACADEMIC OVERVIEW LIST OF PUBLISHED WORKS COMPLETE LIST OF COMPOSITIONS BY GENRE LIST OF PUBLISHED SCORES LIST OF COMMERCIALLY-RELEASED CDs LIST OF SELECTED MAJOR PERFORMANCES RECENT MEDIA BROADCASTING LIST OF COMPOSITION WORKS PERFORMED BY TAMARA SMOLYAR AND OTHER AUSTRALIAN -

TOCC0448DIGIBKLT.Pdf

THE PIANO MUSIC OF LIVIA TEODORESCU-CIOCĂNEA by Joel Crotty Livia Teodorescu-Ciocănea was born in Galaţi, a town in the eastern Romania, on 4 February 1959. She studied piano at the Music and Arts College in Galaţi between 1965 and 1977, where one of her piano teachers was Charlotte Marcovici, who had studied in Vienna in the 1940s. Teodorescu-Ciocănea entered the Ciprian Porumbescu Conservatoire (now the National University of Music) in Bucharest in 1977 and graduated in 1981 with a Bachelor degree in Composition. Her teachers there included Myriam Marbe for composition, Ştefan Niculescu for form and analysis, and Ioana Minei and Ana Pitiş for piano. She turned to PhD studies after the 1989 Romanian revolution, when the system changed and allowed more people to enrol in higher-degree work. She was admitted to a PhD candidature in musicology at the National University of Music in Bucharest in 1996, studying with the composer Anatol Vieru and, later, Octavian Nemescu. In 1998 and 1999 she obtained a Grant for Excellence from the Romanian government, which allowed her to transfer her PhD studies to the University of Huddersfield in the UK for two consecutive years. There she undertook the composition part of her doctorate, studying with Margaret Lucy Wilkins. The result was a doctorate in both musicology and composition. In 1995 she was appointed assistant professor at the National University of Music in Bucharest, teaching form and analysis and orchestration. In 1997 she became a lecturer, and between 2004 and 2015 she worked as an Associate Professor in composition, form and analysis. -

IAML Newsletter N° 27, December 2007

IAML Electronic Newsletter No. 27, December 2007 IAML 2008 Vedi Napoli… … ma non muori. Our next annual confer- ence will take place in Naples (Italy), July 20-25. The web site is already up. Mark your calendar and your bookmarks. Music in libraries Arthur Rubinstein collection to Main Office) in Berlin. By 1947, Rubin- Juilliard School stein had returned to Paris, but it was not The family of pianist Arthur Rubinstein until 1954 that his Paris home was returned (1887-1982) has donated to The Juilliard to him. His final years were spent in Paris School an extensive collection of original and Geneva, where he died in 1982. manuscripts, manuscript copies, and pub- In 1945, the material from Rubinstein’s lished editions seized by the Nazis from library was taken from Berlin to the USSR Rubinstein’s music library in his Paris by the Soviet Army. These 71 items came apartment and recently restituted by the back to Berlin in the course of a partial German government. The 71 items in the return of German cultural assets by the collection were returned in May 2006 to USSR in 1958-59 to the German Democ- the pianist’s four children, Eva Rubinstein, ratic Republic1. The music had been as- Paul Rubinstein, Dr. Alina Rubinstein, and signed to the Music Department of the Ber- John Rubinstein, by New York Consul lin State Library (East) and kept as unproc- General Dr. Hans-Jürgen Helmsoeth. By essed music resources for years. the German government’s own admission, After reunification of the Berlin collec- it marked the first time that Jewish prop- tions, the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foun- erty kept in the Berlin State Library was dation was given responsibility for the re- returned to the legal heirs.