Emotions in Place: the Creation of the Suburban ‘Other’ in Early Modern London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Death, Time and Commerce: Innovation and Conservatism in Styles of Funerary Material Culture in 18Th-19Th Century London

Death, Time and Commerce: innovation and conservatism in styles of funerary material culture in 18th-19th century London Sarah Ann Essex Hoile UCL Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD Declaration I, Sarah Ann Essex Hoile confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature: Date: 2 Abstract This thesis explores the development of coffin furniture, the inscribed plates and other metal objects used to decorate coffins, in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century London. It analyses this material within funerary and non-funerary contexts, and contrasts and compares its styles, production, use and contemporary significance with those of monuments and mourning jewellery. Over 1200 coffin plates were recorded for this study, dated 1740 to 1853, consisting of assemblages from the vaults of St Marylebone Church and St Bride’s Church and the lead coffin plates from Islington Green burial ground, all sites in central London. The production, trade and consumption of coffin furniture are discussed in Chapter 3. Chapter 4 investigates coffin furniture as a central component of the furnished coffin and examines its role within the performance of the funeral. Multiple aspects of the inscriptions and designs of coffin plates are analysed in Chapter 5 to establish aspects of change and continuity with this material. In Chapter 6 contemporary trends in monuments are assessed, drawing on a sample recorded in churches and a burial ground, and the production and use of this above-ground funerary material culture are considered. -

Facial Expression and Emotion Paul Ekman

1992 Award Addresses Facial Expression and Emotion Paul Ekman Cross-cultural research on facial expression and the de- We found evidence of universality in spontaneous velopments of methods to measure facial expression are expressions and in expressions that were deliberately briefly summarized. What has been learned about emo- posed. We postulated display rules—culture-specific pre- tion from this work on the face is then elucidated. Four scriptions about who can show which emotions, to whom, questions about facial expression and emotion are dis- and when—to explain how cultural differences may con- cussed: What information does an expression typically ceal universal in expression, and in an experiment we convey? Can there be emotion without facial expression? showed how that could occur. Can there be a facial expression of emotion without emo- In the last five years, there have been a few challenges tion? How do individuals differ in their facial expressions to the evidence of universals, particularly from anthro- of emotion? pologists (see review by Lutz & White, 1986). There is. however, no quantitative data to support the claim that expressions are culture specific. The accounts are more In 1965 when I began to study facial expression,1 few- anecdotal, without control for the possibility of observer thought there was much to be learned. Goldstein {1981} bias and without evidence of interobserver reliability. pointed out that a number of famous psychologists—F. There have been recent challenges also from psychologists and G. Allport, Brunswik, Hull, Lindzey, Maslow, Os- (J. A. Russell, personal communication, June 1992) who good, Titchner—did only one facial study, which was not study how words are used to judge photographs of facial what earned them their reputations. -

Lecture 2: Theories of Emotion While We Wait Outline

Lecture 2: Theories of Emotion While we wait Outline . Review why emotion theory useful – Give some positive and negative examples . Introduce some features that distinguish different theories – Emotions as discrete or continuious – Emotions as “atoms” or “molecules” – Emotions as a consequence or antecedent of emotin . Review some specific influential theories . Break . In-class “experiment” . Evidence for and against dual-process models of emotion . Appraisal Theory . Review a mental health application of affective computing Why should we care about emotion theory? What is a Theory . Theory explains how some aspect of human behavior or performance is organized. It thus enables us to make predictions about that behavior. – Provides a set of interrelated concepts, definitions, and propositions that explains or predicts aspects of human behavior by specifying relations among variables. – Allows us to explain what we see and to figure out how to bring about change. – Is a tool that enables us to identify a problem and to plan a means for altering the situation. – Create a basis for future research. Researchers use theories to form hypotheses that can then be tested. – Creates a basis for building software: suggests what variables are important to measure and how they relate to each other Example of dangers of atheoretical approaches (e.g., Data Mining) . We’ll learn about machine learning approaches – Collect bunch of data – Look at lots of features and try to predict some outcome Input Predicted features output . Enables us to make predictions about that behavior . Does not typically allows us to explain what we see and to figure out how to bring about change . -

Desiring, Departing and Dying

THE BIBLE & CRITICAL THEORY Desiring, Departing and Dying Affectively Speaking: Epithymia in Philippians 1:23 Sharday C. Mosurinjohn and Richard S. Ascough, Queen’s University Abstract In a text that has caused no shortage of speculation and consternation, Paul links “desire” (epithymia) with “death” in writing of his “desire to depart and be with Christ” (Phil. 1:23). While “desire” has mostly negative valences in Paul’s letters, often linked to sexual craving, here it is linked to his broad fascination with death that is apparent in his frequent references not only to Christ’s crucifixion but also more generally both to physical death and metaphorical death. Paul’s contemplation of which is preferable, life or death, raises questions about how issues of social and existential meaning are affectively negotiated under the aspect of death, under what conditions one desires death, and what is the nature of desire itself. Thinking in this vein suggests an ecology of instincts vital to the affective valences of desiring death. This paper will explore these issues to show how Paul’s own desire may be expressing both a passionate pull to his idea of Christ and a longing to escape that very passion. Keywords Paul; Desire; Death; Affect Theory; Philippians “The anticipation of our own death tells us more about anticipation than it does about death.” (Phillips 2000, 110) Introduction I, (Richard), wrote a disaster of a paper a few years ago, which I presented at a conference and opened with the words, “Well, this was a failed experiment …” It was an attempt to understand an enigmatic, autobiographical clip in one of the letters written by Paul. -

A Silvan Tomkins Handbook Foundations for Affect Theory Adam J

A Silvan Tomkins Handbook Foundations for Affect Theory Adam J. Frank, University of British Columbia Elizabeth Wilson, Emory University Publisher: University of Minnesota Press Publication Place: Minneapolis, MN Publication Date: 2020 Edition: 1 Type of Work: Book | Final Publisher PDF Permanent URL: https://pid.emory.edu/ark:/25593/vgvtq Final published version: https://lccn.loc.gov/2020020378 Copyright information: 2020 by Adam J. Frank and Elizabeth A. Wilson This is an Open Access work distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Accessed October 4, 2021 2:59 AM EDT SURPRISE — STARTLE INTEREST — EXCITEMENT ENJOYMENT — JOY A SHAME — HUMILIATION SILVAN TOMKINS Handbook DISTRESS — ANGUISH FOUNDATIONS FOR AFFECT THEORY ADAM J. FRANK ELIZABETH A. WILSON DISGUST and FEAR — TERROR ANGER — RAGE DISSMELL A Silvan Tomkins Handbook A SILVAN TOMKINS HANDBOOK Foundations for Affect Theory Adam J. Frank and Elizabeth A. Wilson University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis | London This book is freely available in an open access edition thanks to TOME (Toward an Open Monograph Ecosystem)—a collaboration of the Association of American Universities, the Association of University Presses, and the Association of Research Libraries—and the generous support of Emory University and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Learn more at the TOME website, available at: openmonographs.org. Copyright 2020 by Adam J. Frank and Elizabeth A. Wilson A Silvan Tomkins Handbook: Foundations for Affect Theory is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. -

C257 XSM10 Broadgate Ticket Hall Combined Reporting Pits 4 and 11 Tr 14 and 15 Pile

C257 ARCHAEOLOGY CENTRAL Fieldwork Report Archaeological Excavated Evaluations and Watching Briefs Pit 4, Pit 11, Trench 14 and 15, Pile Line Pits and SSET/UKPN Utility Diversions, Broadgate Ticket Hall (XSM10) Document Number: C257-MLA-X-RGN-CRG02-50113 Document History: Revision: Date: Prepared by: Checked by: Approved by: Reason for Issue: 1.0 15.05.12 For CRL Review 2.0 20.06.12 For CRL Review Document uncontrolled once printed. All controlled documents are saved on the CRL Document System © Crossrail Limited RESTRICTED C257 Broadgate Combined Reporting Pits 4 & 11 Tr 14 & 15 Pile Line and SSET Fieldwork Report v2 20-06-12.doc Crossrail Broadgate Ticket Hall Excavated Evaluation and GWBs, Fieldwork Report (XSM10), Doc No. C257-MLA-X-RGN-CRG02-50113 v2 Non-technical summary This report covers two evaluation trenches and four archaeological watching briefs carried out by the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) on the site of the future Crossrail Broadgate Ticket Hall, Liverpool Street, London EC2M, within the City of London. The site consists of the proposed utilities corridor and the Broadgate Ticket Hall construction worksite. It incorporates the western end of the roadway of Liverpool Street, and it’s north and south pavements. The report was commissioned from MOLA by Crossrail Ltd. This work follows a previous phase of archaeological evaluation (ending July 2011). While the results of these latest evaluations and watching briefs broadly confirm anticipated findings, they have led to some re-interpretation of previous evaluation results. Natural terrace gravels were overlaid by weathered natural deposits of alluvial clay, interspersed with occasional bands of gravel. -

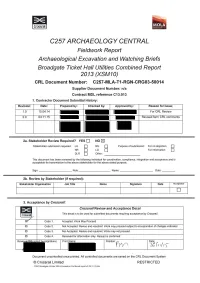

C257 LIS XSM10 Broadgate Utilities WB and Excavation Combined Report.Pdf

Crossrail Broadgate Ticket Hall Excavated Evaluation and GWBs, Fieldwork Report (XSM10) C257-MLA-T1-RGN-CRG03-50014 v2 Non-technical summary This report covers a summary of the results from archaeological fieldwork carried out by Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) on the site of the future Crossrail Broadgate Ticket Hall, Liverpool Street, London EC2M, within the City of London. The site consists of the new utilities corridor and other utilities diversions within the Broadgate Ticket Hall construction worksite. The report was commissioned from MOLA by Crossrail Ltd. The phases of fieldwork covered in this report include the utilities corridor, sewer shafts MHS1 and MHS2-100 and the open cut sewer diversion. A sewer heading leading from MHS2-100 was undertaken as a general watching brief. This fieldwork follows the initial phase of archaeological evaluation in 2010–2011 (MOLA for Crossrail 2012, C257-MLA-X-RGN-CRG02-50064 [v2]) and 2011–2012 (MOLA for Crossrail 2012, C257-MLA-X-XCS-CRG02-50012 [v2]); the current report amalgamates these results in order to further inform the forthcoming excavation of the future ticket hall. Natural terrace gravels were reached in every trench, overlain by waterlain deposits of alluvial clay interspersed with occasional bands of gravel. These are thought to represent episodes of flooding from the Walbrook stream. The eastern edge of the stream itself was present at the western side of the site, running north–south. While a small group of redeposited struck flints was recovered during the fieldwork, there was no tangible evidence for prehistoric activity on the site itself. Evidence was found for several phases of Roman activity, dating to the early 2nd century AD, demonstrating water management in this area of the Walbrook valley. -

AFFECT and SCRIPT: BUILDING RELATIONSHIPS and COMMUNITIES Susan Leigh Deppe, MD, DFAPA October, 2008

AFFECT AND SCRIPT: BUILDING RELATIONSHIPS AND COMMUNITIES Susan Leigh Deppe, MD, DFAPA October, 2008 Drawing on the affect and script paradigm of Silvan S. Tomkins, this two-part workshop will show how restorative practices work. Participants will learn to identify the nine innate affects, biological programs triggered by patterns of neural stimulation, and learn how they motivate all of us. The affects combine with life experience to form scripts, powerful emotional rules, of which we are usually unaware. We will examine the language of emotion, personality development, empathy, intimacy, and some of the scripts by which people manage affects such as shame. Tomkins’s blueprint for emotional health will explain why restorative practices work. Participants will learn common emotional patterns in restorative practices and how healthy communities can help people change. A handout and reference list will be provided. Teaching methods: Lecture/slides, handouts, vignettes, videotape, group discussion EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES: By the conclusion of this presentation, participants should be able to: 1. Understand the importance of the affect system for survival. 2. Be familiar with the nine innate affects and their facial displays. 3. Briefly state the blueprint for emotional health. 4. Recognize the importance of shame, and list four scripts that can be used to manage it. 5. Understand common emotional patterns in restorative practices and how a healthy community can help people change. Susan Leigh Deppe, MD, DFAPA Dr. Deppe is on the Faculty of the Silvan S. Tomkins Institute in Philadelphia, and the University of Vermont College of Medicine. She is in private psychiatric practice. She is a popular teacher at meetings of the American Psychiatric Association, Restorative Practices International, the IIRP, and the Silvan S. -

Churchyard Enhancement Programme Project Briefs for High Priority Churchyards Appendix 2

Churchyard Enhancement Programme Project briefs for high priority churchyards Appendix 2 Name of churchyard 1. St Helen’s Bishopsgate 2. St Anne &St Agnes 3. St Paul’s Cathedral 4. St Bartholomew the Great 5. St Mary Aldermary 6. St Olave Silver Street 7. St Botolph Bishopsgate 8. St Brides Fleet Street 9. Christchurch Greyfriars 10. St Mary at Hill 11. St Peter Westcheap R02 St Helen’s Bishopsgate Churchyard Design Brief (Part of Churchyard Enhancement Programme) 1 Introduction The City of London (City) is the local authority for the ‘Square Mile’, as well as having several private interests. Its policies are dedicated to maintaining the City as one of the world’s leading international financial and business centres; to providing high quality services for its residents and the business communities, and for London, as a whole. The City is also responsible for enhancing and maintaining the network of gardens, churchyards, parks, plazas and highway planting across the City not only for enjoyment by residents, workers and visitors but also as an important habitat for wildlife within the urban landscape 2 Background 2.2 Churchyard Enhancement Programme (CEP) Churchyards within the City are historic open spaces and have collective significance as a cultural asset. They form the setting for the numerous listed churches and ancient monuments, providing a refuge from the City’s intensity and are essential places for workers, visitors and residents to rest and enjoy. Many are popular green spaces; however, others are underutilised, uninspiring and in need of improvement. In the future, the public realm will need to support an increasing City population because of new development and the churchyards are a vital public amenity in this context. -

Universals and Cultural Variations in Emotional Expression by Daniel Thomas Cordaro a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfac

Universals and Cultural Variations in Emotional Expression By Daniel Thomas Cordaro A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Psychology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Dacher Keltner, Chair Professor Iris Mauss Professor Cameron Anderson Spring 2014 1 Abstract Universals and Cultural Variations in Emotional Expression by Daniel Thomas Cordaro Doctor of Philosophy in Psychology University of California, Berkeley Professor Dacher Keltner, Chair One of the most fascinating characteristics of emotions is that they have universal expressive patterns. These expressions, which are encoded through multiple bodily channels, allow us to identify distinct emotions in ourselves and others. After groundbreaking theorizing by Charles Darwin and early empirical work by Ekman and Izard, further research in emotion science revealed evidence in single cultures for more emotional expressions above and beyond the well- studied set comprising of anger, contempt, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. Some of these new emotions were displayed using nonfacial modalities, such as the voice, touch, and posture. Following the logic set forth by these methods and findings, we tested two hypotheses: 1) there are more than seven universal expressions of emotion; 2) expressive universality is not limited to facial expression. Findings from three cross-cultural experimental studies yielded support to the above hypotheses. Our first study collected 5500 expressions of twenty-one emotions from five different cultures. Spontaneous behavioral analysis revealed core facial and bodily patterns for each of the 21 states across all five cultures. Additionally, we uncovered over 100 cultural variations to the universal patterns and hundreds of individual variations. -

LAMAS Newsletter, 84 Lock Chase, Blackheath, London SE3 9HA

CONTENTS Page Notices 2 Reviews and Articles 5 Books and Publications 17 Affiliated Society Meetings 19 NOTICES Newsletter: Copy Date The copy deadline for the September 2017 Newsletter is 21 July 2017. Please send items for inclusion by email preferably (as MS Word attachments) to: [email protected], or by surface mail to me, Richard Gilpin, Honorary Editor, LAMAS Newsletter, 84 Lock Chase, Blackheath, London SE3 9HA. It would be greatly appreciated if contributors could please ensure that any item sent by mail carries postage that is appropriate for the weight and size of the item. **************** New President and Chair of Council At the Annual General Meeting of the Society, held on 14 February 2017, Taryn Nixon was confirmed as the new President of LAMAS – succeeding John Clark, and Harvey Sheldon was confirmed as the new Chair of Council – succeeding Colin Bowlt. **************** New members welcomed by the Local History Committee The LAMAS Local History Committee extends a friendly welcome to members who would like to join the Committee, either as the representative of their affiliated Local History Society or as an individual member of LAMAS. The Committee meets three times a year and in between meetings members carry forward its decisions. Special responsibilities include reading submissions for the LAMAS Publications Awards and deciding on the winners, and organising the Autumn Conference. If you are interested in becoming a member of the Local History Committee – or know of someone in your local society who would like to join the Committee – please get in touch with the Honorary Editor of the Newsletter, Richard Gilpin (email: rhbg.lamas.gmail.com; phone: 020 3774 6726). -

Affect, Temporality, Becoming

Afect, Temporality, Becoming Psychological Anthropology Graduate Seminar ANTH 640 (Winter 2021) Class Schedule T 10.30-1.30PM Location Remote Teaching Professor Samuele Collu Ofce Hours: T 3.00-4.30 PM (Zoom) [email protected] Course Description Tis seminar turns to the making and unmaking of “psychic life” as a way to address the contemporary condition. Trough readings in critical theory, anthropology, and philosophy, the seminar moves away from a personological understanding of the psyche and considers psychic life as a social and collective space that absorbs, hosts, and refracts the passage of historical forces. We engage with afect theory, queer theory, phenomenology, and psychoanalysis to develop psycho-political inquiries about late modern afective attachments, libidinal economies, psycho-cybernetic infrastructures, aesthetic experience, compulsive repetition, visual perception, and psychic (de)territorialization. In parallel, the seminar explores the ethico-political dimensions of the “work of theory” within anthropological regimes of the empirical. Among others, we will read the work of Brian Massumi, Sigmund Freud, Lauren Berlant, Eve Sedgwick, Silvan Tomkins, Teresa Brennan, Sara Ahmed, Bifo Berardi, Natasha Schüll, Han Byung-Chul, and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Recommended Books Gregg, Melissa, and Gregory J. Seigworth, eds. 2010. Te Afect Teory Reader. Duke University Press. Brennan, Teresa. 2004. Te Transmission of Afect. Cornell University Press. Schüll, Natasha Dow. 2012. Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas. Princeton University Press. Course Materials Articles and book chapters will be found on MyCourses. Course Structure and Requirements We will have our seminar discussion every Tuesday (on Zoom). Every Monday (by 6 PM) participants will submit a one/two-page response to the week’s readings.