Revisiting the Historic Preservation Ordinance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SDOT 2018 Traffic Report

Seattle Department of Transportation 2018 TRAFFIC REPORT *2017 data CONTENTS 5 Executive Summary 7 Traffic Volumes and Speeds 8 Motor Vehicle Volumes 11 Traffic Flow Map 13 Bicycle Volumes 18 Pedestrian Volumes 21 Motor Vehicle Speeds 23 Traffic Collisions 24 Citywide Collision Rate 25 Fatal and Serious Injury Collisions 27 Pedestrian Collision Rate 30 Bicycle Collision Rate 33 Supporting Data 33 Volume Data 44 Speed Data 48 Historical Collision Data 50 2016 All Collisions 54 2016 Pedestrian Collisions 63 2016 Bicycle Collisions 75 Glossary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report presents an end of year review of This report is prepared in compliance with Seattle the core data sets the Seattle Department of Municipal Code 11.16.220, which requires the Transportation (SDOT) collects and maintains City Traffic Engineer to present an annual traffic including volumes, speeds, and collisions. The report that includes information about traffic use of this data, guided by department plans and trends and traffic collisions on City of Seattle policies, serves as the foundation for making streets. Beyond this legal requirement, the informed decisions on nearly all work at SDOT report strives to serve as an accessible reference from safety improvements to repaving to grant of Seattle traffic data and trends for all. applications. It is fundamental to measuring project performance. The breadth and depth of In gathering and compiling the information the data collected allows objective discussion of in this report, the Seattle Department of project merits and results, be it a new crosswalk Transportation does not waive the limitations on or an entire safety corridor. As the demands and this information’s discoverability or admissibility complexity of Seattle’s transportation network under 23 U.S.C § 409. -

Canon Law Repeal Canon 19891

CANON LAW REPEAL CANON 19891 Canon 11, 19922 A canon to repeal certain canon law. The General Synod prescribes as follows: 1. This canon may be cited as "Canon Law Repeal Canon 1989". 2. A reference in this or in any other canon to the Canons of 1603 is a reference to the Constitutions and Canons Ecclesiastical agreed upon by the bishops and clergy of the Province of Canterbury in the year of Our Lord 1603 and known as the Canons of 1603 and includes any amendments thereto having force or effect in any part of this Church. 3. (1) Subject to the provisions of the Constitution and the operation of any other canon of the General Synod, all canon law of the Church of England made prior to the Canons of 1603, in so far as the same may have any force, shall have no operation or effect in a diocese which adopts this canon. (2) Nothing in subsection (1) deprives a bishop holding office as a metropolitan and bishop of a diocese, or as the bishop of a diocese, of any inherent power or prerogative, or limit any inherent power or prerogative, that was vested in the metropolitan and bishop of that diocese, or the bishop of that diocese, as the case may be, as holder of those offices or of that office immediately before this canon came into force in that diocese. 4. (1) Subject to this section, the canons numbered 1 to 13 inclusive, 15, 16, 38 to 42 inclusive, 44, 48, 59, 65, 66, 71, 73, 75, 77 to 98 inclusive, 105 to 112 inclusive, 113 (other than the proviso thereto) and 114 to 141 inclusive of the Canons of 1603, in so far as the same may have any force, shall have no operation or effect in a diocese which adopts this canon. -

Harmony of the Law - Volume 4

Harmony of the Law - Volume 4 Author(s): Calvin, John (1509-1564) Calvin, Jean (1509-1564) (Alternative) Bingham, Charles William (Translator) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: Calvin©s Harmony of the Law is his commentary on the books Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. Whereas the majority of Calvin©s commentaries are chronologically arranged--beginning with the first verse in a book, and ending with the last--Harmony of the Law is arranged topically, for Calvin believed that his topical arrangement would better present the various doctrines of "true piety." A remarkable commentary, Harmony of the Law contains Calvin©s discus- sion of the Ten Commandments, the usefulness of the law, and the harmony of the law. Harmony of the Law instructs readers in both the narrative history of the Old Testament and the practical importance and use of the Old Testament teachings. Harmony of the Law is highly recommended, and will demonstrate to a reader why Calvin is regarded as one of the best commentators of the Reformation. Tim Perrine CCEL Staff Writer Subjects: The Bible Works about the Bible i Contents Harmony of the Law, Part 4 1 A Repetition of the Same History (continued) 2 Deuteronomy 1:6-8 2 Numbers 9:17-23 3 Exodus 40:36-38 6 Numbers 10:29-36 7 Numbers 11:1-35 11 Numbers 12:1-16 32 Numbers 13:1-33 41 Deuteronomy 1:19-25 45 Numbers 14:1-9 52 Deuteronomy 1:26-33 57 Numbers 14:10-38 60 Deuteronomy 1:34-36,39,40 72 Numbers 14:39-45 74 Deuteronomy 1:41-46 77 Deuteronomy 9:22-24 79 Deuteronomy -

La W School Graduation to Be Held June 11

Vol. 6, No.5 BOSTON COLLEGE LAW SCHOOL June 1962 LAW REVIEW STAFF HONORED LAW SCHOOL GRADUATION AT PUBLICATIONS DINNER TO BE HELD JUNE 11 BostQn College will confer eight hon Nations since 1958, will receive a doctor orary degrees UPQn leaders in science, of laws degree. government, medicine, the theatre, re Sir Alec Guiness, Academy Award ligion, banking, literature and educatiQn winning actor, will receive a doctor of at its commencement June 11. fine arts degree. Dr. DeHev W. Bronk, president of Ralph Lowell, chairman of the board, the RQckefeller Institute, will be com Boston Safe Deposit and Trust Co. and mencement speaker and receive an 'One of Boston's first citizens in civic, honorary doctor of science, Very Rev. educational, social welfare and business Michael P. Walsh, S.]., president 'Of affairs, will receive a dQctQr of laws the university, has announced. degree. Dr. Br'Onk is also president of the Phyllis McGinley, winner of the National Academy of Sciences and Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1961 , will former president of Johns Hopkins Uni be awarded a doctor 'Of letters degree. versity. Dr. Christopher J. Duncan of Newton, Ralph J. Bunche, under secretary fQr special political affairs at the United (Continued on Page Four) CERTIFICATE OF MERIT WINNERS CHARLES TRETTER--SBA Pres. Nine student members of the Boston ville, N.Y.; John M. Callahan, Hadley, College Industrial and Commercial Law Mass.; Paul G. Delaney, Waterbury, Review' staff were cited at the Annual Conn.; David H. Kravetz, Winthrop, SUZANNE LATAIF--Sec. Publications Banquet held at the law Mass.; Morton R. -

Seattle: Queen City of the Pacific Orn Thwest Anonymous

University of Mississippi eGrove Haskins and Sells Publications Deloitte Collection 1978 Seattle: Queen city of the Pacific orN thwest Anonymous James H. Karales Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/dl_hs Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation DH&S Reports, Vol. 15, (1978 autumn), p. 01-11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Deloitte Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Haskins and Sells Publications by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ^TCAN INSTITUTE OF JC ACCOUNTANTS Queen City Seattle of the Pacific Northwest / eattle, Queen City of the Pacific Located about as far north as the upper peratures are moderated by cool air sweep S Northwest and seat of King County, corner of Maine, Seattle enjoys a moderate ing in from the Gulf of Alaska. has been termed by Harper's and other climate thanks to warming Pacific currents magazines as America's most livable city. running offshore to the west. The normal Few who reside there would disagree. To a maximum temperature in July is 75° Discussing special exhibit which they just visitor, much of the fascination of Seattle Fahrenheit, the normal minimum tempera visited at the Pacific Science Center devoted lies in the bewildering diversity of things to ture in January is 36°. Although the east to the Northwest Coast Indians are (I. to r.) do and to see, in the strong cultural and na ward drift of weather from the Pacific gives DH&S tax accountants Liz Hedlund and tional influences that range from Scandina the city a mild but moist climate, snowfall Shelley Ate and Lisa Dixon, of office vian to Oriental to American Indian, in the averages only about 8.5 inches a year, administration. -

Statement of Qualifications Murray Morgan Bridge Rehabilitation Design-Build Project

Submitted by: Kiewit Pacific Co. Statement of Qualifications Murray Morgan Bridge Rehabilitation Design-Build Project Specification No. PW10-0128F Submitted to: Purchasing Office, Tacoma Public Utilities 3628 South 35th Street, Tacoma, WA 98409 June 8, 2010 Tab No. 1 - General Company Information & Team Structure Murray Morgan Bridge Rehabilitation Design-Build Project Project TAB NO.1 - GENERAL COMPANY INFORMATION AND TEAM STRUCTURE Kiewit Pacific Co., a wholly-owned subsidiary of Kiewit Infrastructure Group, Inc., will be the contracting party for this project, as indicated on Forms 3 and 4 in Tab No. 4 - Appendix C. As a wholly-owned subsidiary, none of the officers of Kiewit Pacific Co. (Kiewit) own stock. Incorporated on May 18, 1982, we can trace our history back to 1884, when Peter and Andrew Kiewit formed Kiewit Brothers, an Omaha masonry contracting partnership. Today, we are part of one of North America's largest and most respected construction and mining organizations. We take our place in the corporate structure of our parent company, Kiewit Infrastructure Group Inc., alongside Kiewit Construction Company and Kiewit Southern Co. Our affiliates and subsidiaries, as well as those of our parent company, operate from a network of offices throughout North America. We draw upon the Kiewit Corporation’s collective experience and personnel to assemble the strongest team possible for a given project. Therefore, work experience of such affiliates and subsidiaries is relevant in demonstrating our capabilities. For the Murray Morgan Bridge, we are supplementing our local talent with extensive moveable bridge expertise from our east coast operations, Kiewit Constructors, Inc. We are also utilizing our local subsidiary, General Construction Company (General), for mechanical and electrical expertise. -

The Artists' View of Seattle

WHERE DOES SEATTLE’S CREATIVE COMMUNITY GO FOR INSPIRATION? Allow us to introduce some of our city’s resident artists, who share with you, in their own words, some of their favorite places and why they choose to make Seattle their home. Known as one of the nation’s cultural centers, Seattle has more arts-related businesses and organizations per capita than any other metropolitan area in the United States, according to a recent study by Americans for the Arts. Our city pulses with the creative energies of thousands of artists who call this their home. In this guide, twenty-four painters, sculptors, writers, poets, dancers, photographers, glass artists, musicians, filmmakers, actors and more tell you about their favorite places and experiences. James Turrell’s Light Reign, Henry Art Gallery ©Lara Swimmer 2 3 BYRON AU YONG Composer WOULD YOU SHARE SOME SPECIAL CHILDHOOD MEMORIES ABOUT WHAT BROUGHT YOU TO SEATTLE? GROWING UP IN SEATTLE? I moved into my particular building because it’s across the street from Uptown I performed in musical theater as a kid at a venue in the Seattle Center. I was Espresso. One of the real draws of Seattle for me was the quality of the coffee, I nine years old, and I got paid! I did all kinds of shows, and I also performed with must say. the Civic Light Opera. I was also in the Northwest Boy Choir and we sang this Northwest Medley, and there was a song to Ivar’s restaurant in it. When I was HOW DOES BEING A NON-DRIVER IMPACT YOUR VIEW OF THE CITY? growing up, Ivar’s had spokespeople who were dressed up in clam costumes with My favorite part about walking is that you come across things that you would pass black leggings. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 1024-0018 (Rev. 8-86) "» United States Department of the Interior ' .J National Park Service Lui « P r% o "•> 10Q1 M!" :\ '~J <* »w3 I National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Registration Form REGISTER This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See Instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the Instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name_________1411 Fourth Avenue Building_____________________________ other names/site number N/A „ 2. Location street & number 1411 Fourth Ave. D not for publication city, town Seattle IZ1 vicinity state Washington code WA county King code 033 zip code 98101 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property IS private K] building(s) Contributing Noncontributing [U public-local C] district 1 _ buildings D public-State IH site _ _ sites C~l public-Federal [U structure _ _ structures CH object objects 1 0 Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously N/A_________________ listed in the National Register 0 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this DO nomination CD request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places ancfVneets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 . -

Estimating PCB and PBDE Loadings to the Lake Washington Watershed: Final Data Report

Estimating PCB and PBDE Loadings to the Lake Washington Watershed: Final Data Report September 2013 Alternate Formats Available 206-296-6519 TTY Relay: 711 Estimating PCB and PBDE Loading Reductions to the Lake Washington Watershed: Final Data Report Prepared for: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 10 Submitted by: Richard Jack and Jenée Colton King County Water and Land Resources Division Department of Natural Resources and Parks Funded by the United States Environmental Protection Agency Grant PC-J28501-1 Disclaimer: This project has been funded wholly or in part by the United States Environmental Protection Agency under assistance agreement PC-00J285-01 to King County. The contents of this document do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Environmental Protection Agency, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. King County i September 2013 Estimating PCBs and PBDEs Loadings to the Lake Washington Watershed: Final Data Report Acknowledgements A fantastic group of people have made this project possible and contributed to its success. Colin Elliott of the King County Environmental Laboratory provided laboratory project management services throughout the field study. Many thanks go to Ben Budka, Marc Patten, David Robinson, Bob Kruger, Jim Devereaux, and Stephanie Hess, who led the year-long field sampling program. The knowledgeable staff at AXYS Analytical Services (AXYS) provided high quality advice and analytical services. Archie Allen and Kirk Tullar of the Washington Department of Transportation provided critical assistance during siting and sampling of the highway bridge runoff location. John Williamson of the Washington Department of Ecology graciously allowed us access and shared space at the Beacon Hill air station. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Bon Marche Department Store other names/site number Bon Marche Building; Macy’s Building 2. Location street & number 300 Pine Street not for publication city or town Seattle vicinity state WASHINGTON code WA county KING code 033 zip code 98122 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X_ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria X A B X C D Signature of certifying official/Title Date WASHINGTON SHPO State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Kirtland Kelsey Cutter, Who Worked in Spokane, Seattle and California

Kirtland Kelsey 1860-1939 Cutter he Arts and Crafts movement was a powerful, worldwide force in art and architecture. Beautifully designed furniture, decorative arts and homes were in high demand from consumers in booming new cities. Local, natural materials of logs, shingles and stone were plentiful in the west and creative architects were needed. One of them was TKirtland Kelsey Cutter, who worked in Spokane, Seattle and California. His imagination reflected the artistic values of that era — from rustic chapels and distinctive homes to glorious public spaces of great beauty. Cutter was born in Cleveland in 1860, the grandson of a distinguished naturalist. A love of nature was an essential part of Kirtland’s work and he integrated garden design and natural, local materials into his plans. He studied painting and sculp- ture in New York and spent several years traveling and studying in Europe. This exposure to art and culture abroad influenced his taste and the style of his architecture. The rural buildings of Europe inspired him throughout his career. One style associated with Cutter is the Swiss chalet, which he used for his own home in Spokane. Inspired by the homes of the Bernese Oberland region of Switzerland, it featured deep eaves that extended out from the roofline. The inside was pure Arts and Crafts, with a rustic, tiled stone fireplace, stained glass windows and elegant woodwork. Its simplicity contrasted with the grand homes many of his clients requested. The railroads brought people to the Northwest looking for opportunities in mining, logging and real estate. My great grandfather, Victor Dessert, came from France and settled in Spokane in the 1880s. -

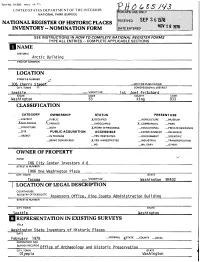

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Arctic Building AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 306 Cherry Si _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN & CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Seattle __ VICINITY OF 1 st Joel Pri tchard STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Washington 53 King 033 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC XOCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) ^-PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED ^-COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH X-WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED XYES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: CHG Citv Center Investors # 6 STREET & NUMBER 1906 One Washington Plaza CITY, TOWN STATE ____Tacoma VICINITY OF Washington 98402 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEED^ETC. Assessors Qff| ce , King County Admi ni s trati on Buil di nq STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Seattle Washington REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Washington State Inventory of Historic Places DATE February 1978 —FEDERAL ^STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Qff1ce Of Archaeology and Historic Preservation CITY. TOWN STATE Olympia Washington DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE —RUINS X_ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Arctic Building,occupying a site at the corner of Third Avenue and Cherry Street in Seattle, rises eight stories above a ground level of retail shops to an ornate terra cotta roof cornice.