Occasional Beasts: Tales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

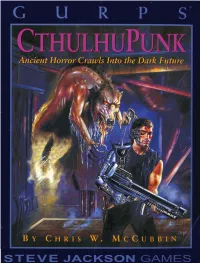

I STEVE JACKSON GAMES ,; Ancient Howor Crawls Into the Dark Future

I STEVE JACKSON GAMES ,; Ancient Howor Crawls into the Dark Future By Chris W. McCubbin Edited by Scott D. Haring Cover by Albert Slark Illustrated by Dan Smith GURPS System Design by Steve Jackson Scott Haring, Managing Editor Page Layout, Typography and Interior Production by Rick Martin Cover Production by Jeff Koke Art Direction by Lillian Butler Print Buying by Andrew Hartsock and Monica Stephens Dana Blankenship, Sales Manager Thanks to Dm Smith Additional Material by David Ellis Dickerson Bibliographic information compiled by Chris Jarocha-Emst Proofreading by Spike Y. Jones Playtesters: Bob Angell, Sean Barrett, Kaye Barry, C. Milton Beeghly, James Cloos, Mike DeSanto, Morgan Goulet, David G. Haren, Dave Magnenat, Virginia L. Nelson, James Rouse, Karen Sakamoto, Michael Sullivan and Craig Tsuchiya GURPS and the all-seeing pyramid are registered trademarks of Steve Jackson Games Incorporated. Pyramid and the names of all products published by Steve Jackson Games Incorporated are registered trademarks or trademarks of Steve Jackson Games Incorporated, or used under license. Cull of Cihulhu is a trademark of Chaosium Inc. and is used by permission. Elder Sign art (p. 55) used by permission of Chaosium Inc. GURPS CihuIhuPunk is copyright 0 1995 by Steve Jackson Games Incorporated. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A ISBN 1-55634-288-8 Introduction ................................ 4 Central and South America ..27 Hacker ..................................43 About GURPS ............................4 The Pacific Rim ...................27 -

Hypersphere Anonymous

Hypersphere Anonymous This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. ISBN 978-1-329-78152-8 First edition: December 2015 Fourth edition Part 1 Slice of Life Adventures in The Hypersphere 2 The Hypersphere is a big fucking place, kid. Imagine the biggest pile of dung you can take and then double-- no, triple that shit and you s t i l l h a v e n ’ t c o m e c l o s e t o o n e octingentillionth of a Hypersphere cornerstone. Hell, you probably don’t even know what the Hypersphere is, you goddamn fucking idiot kid. I bet you don’t know the first goddamn thing about the Hypersphere. If you were paying attention, you would have gathered that it’s a big fucking 3 place, but one thing I bet you didn’t know about the Hypersphere is that it is filled with fucked up freaks. There are normal people too, but they just aren’t as interesting as the freaks. Are you a freak, kid? Some sort of fucking Hypersphere psycho? What the fuck are you even doing here? Get the fuck out of my face you fucking deviant. So there I was, chilling out in the Hypersphere. I’d spent the vast majority of my life there, in fact. It did contain everything in my observable universe, so it was pretty hard to leave, honestly. At the time, I was stressing the fuck out about a fight I had gotten in earlier. I’d been shooting some hoops when some no-good shithouses had waltzed up to me and tried to make a scene. -

Brand New Deja Entendu Torrent

Brand new deja entendu torrent Continue DOWNLOAD - ��▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀Band........................... Brand NewAlbum............... Deja EntenduYear............................ 2003Genre................... Indie rock, emo, quality . MP3 192 kbit/sArchive file............. rar and .zipCountry................... The United Stateslanguage ............ EnglishOffic site.. TautouSic Transit Gloria Glory FadesI will play my game under the spin lightOkay I believe you, But my Tommy Gun Don't The Silent Things That No One Never KnowThe Boy Who Blocked His Own ShotJaws Theme SwimmingMe vs. Maradona vs. ElvisGuernicaGood know that if I ever need the attention all I have to do is DiePlay Crack Sky Huge thanks to Justin for requesting this group who just turned out to be the perfect band to make this blog 100th post. So, without further ado, I give you the best band ever, Brand New. Thanks to Shadman and Nick for their help with this post as well. Brand New is from Long Island, New York, and was formed in 2000. This group had their roots in another group called Rookie Lot, which three Long Island kids named Jesse Lacey, Garrett Tierney, and Brian Lane were in, along with two other members (who eventually join Crime in Stereo and Movielife respectively). The three remaining members, along with the addition of Vin Accardi (formerly One Last Goodbye), came together to form a new group. Vuala, Brand New. After several demos, they put out their debut in 2001 on Triple Crown Records. At this time they wrote catchy pop-punk songs full of teenage bitterness (well). Their next release, Deja Entendu, showed their maturation as a band and reaching a much larger audience. -

Universidade Federal De Santa Catarina Pós

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS/INGLÊS E LITERATURA CORRESPONDENTE WEIRD FICTION AND THE UNHOLY GLEE OF H. P. LOVECRAFT KÉZIA L’ENGLE DE FIGUEIREDO HEYE Dissertação Submetida à Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina em cumprimento dos requisitos para obtenção do grau de MESTRE EM LETRAS Florianópolis Fevereiro, 2003 My heart gave a sudden leap of unholy glee, and pounded against my ribs with demoniacal force as if to free itself from the confining walls of my frail frame. H. P. Lovecraft Acknowledgments: The elaboration of this thesis would not have been possible without the support and collaboration of my supervisor, Dra. Anelise Reich Courseil and the patience of my family and friends, who stood by me in the process of writing and revising the text. I am grateful to CAPES for the scholarship received. ABSTRACT WEIRD FICTION AND THE UNHOLY GLEE OF H. P. LOVECRAFT KÉZIA L’ENGLE DE FIGUEIREDO HEYE UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA 2003 Supervisor: Dra. Anelise Reich Corseuil The objective of this thesis is to verify if the concept of weird fiction can be classified not only as a sub-genre of the horror literary genre, but if it constitutes a genre of its own. Along this study, I briefly present the theoretical background on genre theory, the horror genre, weird fiction, and a review of criticism on Lovecraft’s works. I also expose Lovecraft’s letters and ideas, expecting to show the working behind his aesthetic theory on weird fiction. The theoretical framework used in this thesis reflects some of the most relevant theories on genre study. -

Bloch the Best of Edmond Hamilton Introduction by Leigh Brackett the Best of Leigh Brackett Introduction by Edmond Hamilton *The Best of L

THE STALKING DEAD The lights went out. Somebody giggled. I heard footsteps in the darkness. Mutter- ings. A hand brushed my face. Absurd, standing here in the dark with a group of tipsy fools, egged on by an obsessed Englishman. And yet there was real terror here . Jack the Ripper had prowled in dark ness like this, with a knife, a madman's brain and a madman's purpose. But Jack the Ripper was dead and dust these many years—by every human law . Hollis shrieked; there was a grisly thud. The lights went on. Everybody screamed. Sir Guy Hollis lay sprawled on the floor in the center of the room—Hollis, who had moments before told of his crack-brained belief that the Ripper still stalked the earth . The Critically Acclaimed Series of Classic Science Fiction NOW AVAILABLE: The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum Introduction by Isaac Asimov The Best of Fritz Leiber Introduction by Poul Anderson The Best of Frederik Pohl Introduction by Lester del Rey The Best of Henry Kuttne'r Introduction by Ray Bradbury The Best of Cordwainer Smith Introduction by J. J. Pierce The Best of C. L. Moore Introduction by Lester del Rey The Best of John W. Campbell Introduction by Lester del Rey The Best of C. M. Kornbluth Introduction by Frederik Pohl The Best of Philip K. Dick Introduction by John Brunner The Best of Fredric Brown Introduction by Robert Bloch The Best of Edmond Hamilton Introduction by Leigh Brackett The Best of Leigh Brackett Introduction by Edmond Hamilton *The Best of L. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Gangster Boogie: Los Angeles and the Rise of Gangsta Rap, 1965-1992 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3hd2d12n Author Viator, Felicia Angeja Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Gangster Boogie: Los Angeles and the Rise of Gangsta Rap, 1965-1992 By Felicia Angeja Viator A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Leon F. Litwack, Co-Chair Professor Waldo E. Martin, Jr., Co-Chair Professor Scott Saul Fall 2012 Abstract Gangster Boogie: Los Angeles and the Rise of Gangsta Rap, 1965-1992 by Felicia Angeja Viator Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Leon F. Litwack, Co-Chair Professor Waldo E. Martin, Jr., Co-Chair “Gangster Boogie” details the early development of hip-hop music in Los Angeles, a city that, in the 1980s, the international press labeled the “murder capital of the U.S.” The rap music most associated with the region, coined “gangsta rap,” has been regarded by scholars, cultural critics, and audiences alike as a tabloid distortion of East Coast hip-hop. The dissertation shows that this uniquely provocative genre of hip-hop was forged by Los Angeles area youth as a tool for challenging civic authorities, asserting regional pride, and exploiting the nation’s growing fascination with the ghetto underworld. Those who fashioned themselves “gangsta rappers” harnessed what was markedly difficult about life in black Los Angeles from the early 1970s through the Reagan Era––rising unemployment, project living, crime, violence, drugs, gangs, and the ever-increasing problem of police harassment––to create what would become the benchmark for contemporary hip-hop music. -

Monophobia a Fear of Solitude

MONOPHOBIA A FEAR OF SOLITUDE AN OPUSCULE OF ADVENTURES FOR LONE INVESTIGATORS IN THE WORLD OF CHAOSIUM’S CALL OF CTHULHU™ Written by Mark Chiddicks and Marcus D. Bone Art by Ashley Jones | Editing by James King UNBOUND PUBLISHING UBB #1001 ©2010 Unbound Publishing Visit us @ www.unboundbook.org Dedication To Tim Wiseman & Ashley Jones – True Avatars of the King in Yellow and all round nice guys to boot! Without you both this would still be nothing but an unrealised dream & In Remembrance of Keith ‘Doc’ Herber - A Master of Adventure who will be missed… Call of Cthulhu is a horror roleplaying game published by Chaosium Inc © 2008 22568 Mission Boulevard #423 Hayward CA 94541-5116 Phone 510-583-1000 Fax 510-583-1101 MONOPHOBIA: A FEAR OF SOLITUDE is an opuscule created by Mark Chiddicks and Marcus D. Bone. In clear credit, Mark Chiddicks is responsible for Madness from the Grave and Robinson Gruesome, while Marcus D. Bone is responsible for Of Grave Concern and the layout & design of this manuscript © 2010. The cover The Cthulhu Scream and artwork Sketch of Ethan Blane are © 2008 Ashley Jones. Eight years in the making, this opuscule would not have been possible without the playtester assistance of Mark Hockey and Darryn Mercer, the editing expertise of James King, and the enthusiastic cheers of various others. About the Authors Mark writes Mark is a transplanted Englishman who moved to New Zealand in the 1990s to be closer to R’lyeh when it rises. He’s been playing Call of Cthulhu since 1984 and is sure it hasn’t affected him at all. -

Necronomicon.Pdf

1 NECRONOMICON FROM FICTION TO FALSIFYING HISTORY A STUDY OF A CONCEPT BY H.P. LOVECRAFT WILMAR TAAL Cover image: Illuminatus 1 (1978) by H.R. Giger 2 © 2017 Wilmar Taal. First edition PDF March 2017. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored within a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, scanning, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permisson of the author. 3 PREFACE Nine years of study and work are before you, accompanied by a lot of thinking and one bright idea. After I disapproved many subjects for my thesis, being much too broad, a visit by my second cousin brought me to a literary study of Lovecraft’s Necronomicon, a work of fiction considered real by many readers of Lovecraft’s work. Although my thesis was interactive (a CD Rom accompanied my thesis), this online translated version has more similarities with a book than an interactive thesis. In the 2017 version there are also some additions made, like the Tyson Necronomicon which was published after I graduated university. It doesn’t affect the conclusion written to this thesis. Furthermore it is a representation of the thesis I delivered to the University in 2004. This means that it is not the original work, I have taken the liberty to add some information, but also to leave some things out. I have decided not to include the summary, the notes and the sources. This is a free online sample which can be requested through my websites. -

Springtime at Fairchild

spring 2011 Springtime at Fairchild; a treasure trove of Jade published by fairchild tropical botanic garden tropical gourmet foods home décor accessories eco-friendly and fair trade products gardening supplies unique tropical gifts books on tropical gardening, cuisine and more Fern Temple Jar, $240 Photo by Gaby Orihuela/FTBG. Sign up today for The Shop at Fairchild’s frequent shopper program! After you make six merchandise purchases, we’ll add them all up and give you 10% of the total back in rewards dollars to spend in the store. fairchild tropical botanic garden 10901 Old Cutler Road, Coral Gables, FL 33156 • 305.667.1651, ext. 3305 • www.fairchildgarden.org • shop online at www.fairchildonline.com contents CONSERVING EARTH BEHIND THE SCENES FROM SPACE 28 34 Two Men Who Helped the Garden Take Root DEPARTMENTS 5 FROM THE DIRECTOR 8 EVENTS 9 NEWS 11 TROPICAL CUISINE 12 WHAT’S BLOOMING 15 EXPLAINING 19 VIS-A-VIS VOLUNTEERS 27 PLANT SOCIETIES 46 BUG BEAT 49 SOUTH FLORIDA GARDENING SUMMER VEGETABLES 42 51 WISH LIST 52 GIFTS AND DONORS 54 VISTAS 59 WHAT’S IN STORE 60 GARDEN VIEWS 64 FROM THE ARCHIVES 66 CONNECT WITH FAIRCHILD Membership at Fairchild Members of Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden make a big difference, because they are part of a global community focused on tropical plant conservation and education. Fairchild members support programs in faraway places like Madagascar and Kenya. Fairchild members support conservation and education programs right here in South Florida. In fact, Fairchild’s scientists are leading plant conservation efforts in our local areas and neighborhoods. -

Pitchfork Mental Health

“NAME ONE GENIUS THAT AIN’T CRAZY”- MISCONCEPTIONS OF MUSICIANS AND MENTAL HEALTH IN THE ONLINE STORIES OF PITCHFORK MAGAZINE _____________________________________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri-Columbia ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________ By Jared McNett Dr Berkley Hudson, Thesis Supervisor December 2016 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled “NAME ONE GENIUS THAT AIN’T CRAZY”- MISCONCEPTIONS OF MUSICIANS AND MENTAL HEALTH IN THE ONLINE STORIES OF PITCHFORK MAGAZINE presented by Jared McNett, A candidate for the degree of masters of art and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Berkley Hudson Professor Cristina Mislan Professor Jamie Arndt Professor Andrea Heiss Acknowledgments It wouldn’t be possible to say thank enough to each and every person that has helped me with this along my way. I’m thankful for my parents, Donald and Jane McNett, who consistently pestered me by asking “How’s it coming with your thesis? Are you done yet?” I’m thankful for friends, such as: Adam Suarez, Phillip Sitter, Brandon Roney, Robert Gayden and Zach Folken, who would periodically ask me “What’s your thesis about again?” That was a question that would unintentionally put me back on track. In terms of staying on task my thesis committee (mentioned elsewhere) was nothing short of a godsend. It hasn’t been an easy two-and-a-half years going from basic ideas to a proposal to a thesis, but Drs. -

Being Romantic’, Agency and the (Re)Production and (Re)Negotiation of Traditional Gender Roles

‘BEING ROMANTIC’, AGENCY AND THE (RE)PRODUCTION AND (RE)NEGOTIATION OF TRADITIONAL GENDER ROLES Nicola Human November, 2018 University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg 1 Declaration This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the graduate Programme of Psychology, School of Applied Human Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. I, Nicola Human, declare as follows: 1. The data and arguments presented in this thesis – except where otherwise indicated – represents my original work. This research does not contain data in the form of pictures, graphs, or other information from someone else’s work or from the Internet, unless specifically indicated and referenced. This research does not contain the writing of someone else, unless specifically acknowledged as such. (a) Where someone else’s ideas have been used, they have been rewritten in my own words and attributed to them. (b) When someone else’s words have been used exactly, these have been referenced according to the American Psychological Association guidelines. 2. Two UKZN Psychology Honours research projects were conducted as off-shoots to this study in 2014. Both studies were co-supervised by myself and my supervisor Dr Michael Quayle and were submitted in October, 2014. (a) In the first study, my data from Couples 1, 2 and 5 were analysed by Yamiska Naidoo (student number: 211517798) and Nondumiso Qwabe (student number, 211502797) for their project, titled “A qualitative investigation of how South African men and women produce romantic masculinity, and its relationship to hegemonic masculinity”. Written permission was acquired from the participants and an independent application to the Ethics Panel was approved for the students to use this data. -

Ravel Biography.Pdf

780.92 R2528g Goss Bolero, the life of Maurice Ravel, Kansas city public library Kansas city, missouri Books will be issued only on presentation of library card. Please report lost cards and change of residence promptly. Card holders are responsible for all books, records, films, pictures or other library materials checked out on their cards. 3 1148 00427 6440 . i . V t""\ 5 iul. L-* J d -I- (. _.[_..., BOLERO THE LIFE OF MAURICE .RAVEL '/ ^Bpofas fay Madeleine Goss : BEETHOVEN, MASTER MUSICIAN DEEP-FLOWING BROOK: The Story of Johann Sebastian Bach (for younger readers) BOLERO : The Life of Maurice Ravel Maurice Ravel, Manuel from a photograph by Henri BOLERO THE LIFE OF MAURICE RAVEL BY MADELEINE GOSS "De la musique avant toute chose, De la musique encore et toujours." Verlaine NEW YORK HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY Wfti^zsaRD UNIVERSITY PRESS COPYRIGHT, IQ40, BY HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY, INC. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA '.'/I 19 '40 To the memory of my son ALAN who, in a sense, inspired this work CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. Bolero 1 II. Childhood on the Basque Coast . 14 III. The Paris Conservatory in Ravel's Time 26 IV. He Begins to Compose .... 37 V. Gabriel Faure and His Influence on Ravel 48 VI. Failure and Success .... 62 VII. Les Apaches 74 VIII. The Music of Debussy and Ravel . 87 IX. The "Stories from Nature" ... 100 X. The Lure of Spain 114 XL Ma Mere VOye 128 XII. Daphnis and Chloe 142 XIII. The "Great Year of Ballets" ... 156 XIV. Ravel Fights for France ...