UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking Intellectual Property Into Their Own Hands

Taking Intellectual Property into Their Own Hands Amy Adler* & Jeanne C. Fromer** When we think about people seeking relief for infringement of their intellectual property rights under copyright and trademark laws, we typically assume they will operate within an overtly legal scheme. By contrast, creators of works that lie outside the subject matter, or at least outside the heartland, of intellectual property law often remedy copying of their works by asserting extralegal norms within their own tight-knit communities. In recent years, however, there has been a growing third category of relief-seekers: those taking intellectual property into their own hands, seeking relief outside the legal system for copying of works that fall well within the heartland of copyright or trademark laws, such as visual art, music, and fashion. They exercise intellectual property self-help in a constellation of ways. Most frequently, they use shaming, principally through social media or a similar platform, to call out perceived misappropriations. Other times, they reappropriate perceived misappropriations, therein generating new creative works. This Article identifies, illustrates, and analyzes this phenomenon using a diverse array of recent examples. Aggrieved creators can use self-help of the sorts we describe to accomplish much of what they hope to derive from successful infringement litigation: collect monetary damages, stop the appropriation, insist on attribution of their work, and correct potential misattributions of a misappropriation. We evaluate the benefits and demerits of intellectual property self-help as compared with more traditional intellectual property enforcement. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38KP7TR8W Copyright © 2019 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Inc. -

An N U Al R Ep O R T 2018 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 ANNUAL REPORT The Annual Report in English is a translation of the French Document de référence provided for information purposes. This translation is qualified in its entirety by reference to the Document de référence. The Annual Report is available on the Company’s website www.vivendi.com II –— VIVENDI –— ANNUAL REPORT 2018 –— –— VIVENDI –— ANNUAL REPORT 2018 –— 01 Content QUESTIONS FOR YANNICK BOLLORÉ AND ARNAUD DE PUYFONTAINE 02 PROFILE OF THE GROUP — STRATEGY AND VALUE CREATION — BUSINESSES, FINANCIAL COMMUNICATION, TAX POLICY AND REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT — NON-FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE 04 1. Profile of the Group 06 1 2. Strategy and Value Creation 12 3. Businesses – Financial Communication – Tax Policy and Regulatory Environment 24 4. Non-financial Performance 48 RISK FACTORS — INTERNAL CONTROL AND RISK MANAGEMENT — COMPLIANCE POLICY 96 1. Risk Factors 98 2. Internal Control and Risk Management 102 2 3. Compliance Policy 108 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE OF VIVENDI — COMPENSATION OF CORPORATE OFFICERS OF VIVENDI — GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE COMPANY 112 1. Corporate Governance of Vivendi 114 2. Compensation of Corporate Officers of Vivendi 150 3 3. General Information about the Company 184 FINANCIAL REPORT — STATUTORY AUDITORS’ REPORT ON THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS — CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS — STATUTORY AUDITORS’ REPORT ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS — STATUTORY FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 196 Key Consolidated Financial Data for the last five years 198 4 I – 2018 Financial Report 199 II – Appendix to the Financial Report 222 III – Audited Consolidated Financial Statements for the year ended December 31, 2018 223 IV – 2018 Statutory Financial Statements 319 RECENT EVENTS — OUTLOOK 358 1. Recent Events 360 5 2. Outlook 361 RESPONSIBILITY FOR AUDITING THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 362 1. -

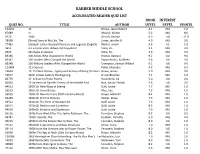

Barber Middle School Accelerated Reader Quiz List Book Interest Quiz No

BARBER MIDDLE SCHOOL ACCELERATED READER QUIZ LIST BOOK INTEREST QUIZ NO. TITLE AUTHOR LEVEL LEVEL POINTS 124151 13 Brown, Jason Robert 4.1 MG 5.0 87689 47 Mosley, Walter 5.3 MG 8.0 5976 1984 Orwell, George 8.9 UG 17.0 78958 (Short) Story of My Life, The Jones, Jennifer B. 4.0 MG 3.0 77482 ¡Béisbol! Latino Baseball Pioneers and Legends (English) Winter, Jonah 5.6 LG 1.0 9611 ¡Lo encontramos debajo del fregadero! Stine, R.L. 3.1 MG 2.0 9625 ¡No bajes al sótano! Stine, R.L. 3.9 MG 3.0 69346 100 Artists Who Changed the World Krystal, Barbara 9.7 UG 9.0 69347 100 Leaders Who Changed the World Paparchontis, Kathleen 9.8 UG 9.0 69348 100 Military Leaders Who Changed the World Crompton, Samuel Willard 9.1 UG 9.0 122464 121 Express Polak, Monique 4.2 MG 2.0 74604 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and Ecstasy of Being Thirteen Howe, James 5.0 MG 9.0 53617 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Grace/Bruchac 7.1 MG 1.0 66779 17: A Novel in Prose Poems Rosenberg, Liz 5.0 UG 4.0 80002 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East Nye, Naomi Shihab 5.8 UG 2.0 44511 1900-10: New Ways of Seeing Gaff, Jackie 7.7 MG 1.0 53513 1900-20: Linen & Lace Mee, Sue 7.3 MG 1.0 56505 1900-20: New Horizons (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 8.4 MG 1.0 62439 1900-20: Print to Pictures Parker, Steve 7.3 MG 1.0 44512 1910-20: The Birth of Abstract Art Gaff, Jackie 7.6 MG 1.0 44513 1920-40: Realism and Surrealism Gaff, Jackie 8.3 MG 1.0 44514 1940-60: Emotion and Expression Gaff, Jackie 7.9 MG 1.0 36116 1940s from World War II to Jackie Robinson, The Feinstein, Stephen 8.3 -

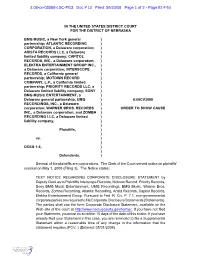

4:08-Cv-03088-LSC-FG3 Doc # 10 Filed: 06/20/08 Page 1 of 2 - Page ID # 64

4:08-cv-03088-LSC-FG3 Doc # 10 Filed: 06/20/08 Page 1 of 2 - Page ID # 64 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEBRASKA BMG MUSIC, a New York general ) partnership; ATLANTIC RECORDING ) CORPORATION, a Delaware corporation; ) ARISTA RECORDS LLC, a Delaware ) limited liability company; CAPITOL ) RECORDS, INC., a Delaware corporation; ) ELEKTRA ENTERTAINMENT GROUP INC., ) a Delaware corporation; INTERSCOPE ) RECORDS, a California general ) partnership; MOTOWN RECORD ) COMPANY, L.P., a California limited ) partnership; PRIORITY RECORDS LLC, a ) Delaware limited liability company; SONY ) BMG MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT, a ) Delaware general partnership; UMG ) 4:08CV3088 RECORDINGS, INC., a Delaware ) corporation; WARNER BROS. RECORDS ) ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE INC., a Delaware corporation; and ZOMBA ) RECORDING LLC, a Delaware limited ) liability company, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) vs. ) ) DOES 1-6, ) ) Defendants. ) Several of the plaintiffs are corporations. The Clerk of the Court served notice on plaintiffs' counsel on May 1, 2008 (Filing 3). The Notice states: TEXT NOTICE REGARDING CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT by Deputy Clerk as to Plaintiffs Interscope Records, Motown Record, Priority Records, Sony BMG Music Entertainment, UMG Recordings, BMG Music, Warner Bros. Records, Zomba Recording, Atlantic Recording, Arista Records, Capitol Records, Elektra Entertainment Group. Pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 7.1, non-governmental corporate parties are required to file Corporate Disclosure Statements (Statements). The parties shall use the form Corporate Disclosure Statement, available on the Web site of the court at http://www.ned.uscourts.gov/forms/. If you have not filed your Statement, you must do so within 15 days of the date of this notice. If you have already filed your Statement in this case, you are reminded to file a Supplemental Statement within a reasonable time of any change in the information that the statement requires.(PCV, ) (Entered: 05/01/2008) 4:08-cv-03088-LSC-FG3 Doc # 10 Filed: 06/20/08 Page 2 of 2 - Page ID # 65 Fed. -

Celebrity and Race in Obama's America. London

Cashmore, Ellis. "To be spoken for, rather than with." Beyond Black: Celebrity and Race in Obama’s America. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012. 125–135. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 29 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781780931500.ch-011>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 29 September 2021, 05:30 UTC. Copyright © Ellis Cashmore 2012. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 11 To be spoken for, rather than with ‘“I’m not going to put a label on it,” said Halle Berry about something everyone had grown accustomed to labeling. And with that short declaration she made herself arguably the most engaging black celebrity.’ uperheroes are a dime a dozen, or, if you prefer, ten a penny, on Planet SAmerica. Superman, Batman, Captain America, Green Lantern, Marvel Girl; I could fi ll the rest of this and the next page. The common denominator? They are all white. There are benevolent black superheroes, like Storm, played most famously in 2006 by Halle Berry (of whom more later) in X-Men: The Last Stand , and Frozone, voiced by Samuel L. Jackson in the 2004 animated fi lm The Incredibles. But they are a rarity. This is why Will Smith and Wesley Snipes are so unusual: they have both played superheroes – Smith the ham-fi sted boozer Hancock , and Snipes the vampire-human hybrid Blade . Pulling away from the parallel reality of superheroes, the two actors themselves offer case studies. -

Free Views Tiktok

Free Views Tiktok Free Views Tiktok CLICK HERE TO ACCESS TIKTOK GENERATOR tiktok auto liker hack In July 2021, "The Wall Street Journal" reported the company's annual revenue to be approximately $800 million with a loss of $70 million. By May 2021, it was reported that the video-sharing app generated $5.2 billion in revenue with more than 500 million users worldwide.", free vending machine code tiktok free pro tiktok likes and followers free tiktok fans without downloading any apps The primary difference between Tencent’s WeChat and ByteDance’s Toutiao is that the former has yet to capitalize on the addictive nature of short-form videos, whereas the latter has. TikTok — the latter’s new acquisition — is a comparatively more simple app than its parent company, but it does fit in well with Tencent’s previous acquisition of Meitu, which is perhaps better known for its beauty apps.", In an article published by The New York Times, it was claimed that "An app with more than 500 million users can’t seem to catch a break. From pornography to privacy concerns, there have been quite few controversies surrounding TikTok." It continued by saying that "A recent class-action lawsuit alleged that the app poses health and privacy risks to users because of its allegedly discriminatory algorithm, which restricts some content and promotes other content." This article was published on The New York Times.", The app has received criticism from users for not creating revenue and posting ads on videos which some see as annoying. The app has also been criticized for allowing children younger than age 13 to create videos. -

Music 18145 Songs, 119.5 Days, 75.69 GB

Music 18145 songs, 119.5 days, 75.69 GB Name Time Album Artist Interlude 0:13 Second Semester (The Essentials Part ... A-Trak Back & Forth (Mr. Lee's Club Mix) 4:31 MTV Party To Go Vol. 6 Aaliyah It's Gonna Be Alright 5:34 Boomerang Aaron Hall Feat. Charlie Wilson Please Come Home For Christmas 2:52 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Holy Night 4:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Christmas Song 4:20 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! 2:22 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville White Christmas 4:48 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Such A Night 3:24 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Little Town Of Bethlehem 3:56 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Silent Night 4:06 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Louisiana Christmas Day 3:40 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Star Carol 2:13 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Bells Of St. Mary's 2:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:42 Billboard Top R&B 1967 Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:41 Classic Soul Ballads: Lovin' You (Disc 2) Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven 4:38 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville I Owe You One 5:33 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Don't Fall Apart On Me Tonight 4:24 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville My Brother, My Brother 4:59 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Betcha By Golly, Wow 3:56 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Song Of Bernadette 4:04 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville You Never Can Tell 2:54 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Bells 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville These Foolish Things 4:23 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Roadie Song 4:41 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Ain't No Way 5:01 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Grand Tour 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Lord's Prayer 1:58 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:43 Smooth Grooves: The 60s, Volume 3 L.. -

Blu-Raydefinition.Com » X — the Unheard Music: Silver Edition Blu-Ray

Blu-rayDefinition.com » X — The Unheard Music: Silver Edition Blu-ray... http://www.blu-raydefinition.com/reviews/x-the-unheard-music-silver-edi... User Name Remember Me? Password Register Blu-rayDefinition.com Home News Reviews Hardware Contact Forum Community Movie Genre 20th Century Fox (91) 2L (5) A&E (15) ABC Family (1) ABC Studios (1) Accentus (7) Action (283) Adult Swim (2) Adventure (62) AIX (2) Anchor Bay Entertainment (39) Animation (157) Anime (82) Art House (44) Arthaus Musik (12) Artificial Eye (8) Asian Cinema (55) Astronomy (4) Australian (1) Automotive (4) Avant-garde (8) Ballet (15) BBC (41) Bel Air Classiques (1) BFI (31) Biopic (33) Blu-ray 3D (20) Blu-ray Audio (18) Blues (1) Bounty Films (2) British (52) 1 of 22 1/4/2012 2:20 PM Blu-rayDefinition.com » X — The Unheard Music: Silver Edition Blu-ray... http://www.blu-raydefinition.com/reviews/x-the-unheard-music-silver-edi... C Major (16) Capitol Records (2) Cartoon Network (4) Chamber Music (1) Chelsea Cinema (1) Choral/Oratorio (1) Classic Rock (3) Classical Music (85) Columbia Pictures (2) Columbia Records (1) Comedy (208) Comedy Central (2) Comic Books/Graphic Novels (19) Concert/Music (75) Crime (109) Criterion (50) Czech Language (1) Dacapo (1) Dance (16) Dark Comedy (20) Dark Sky Films (1) Demoscene (1) Dimension Films (2) Direct-to-Video (8) Discovery Channel (1) DisneyNature (3) Docudrama (31) Documentary (84) Drama (416) DreamWorks (6) Eagle Rock (32) Educational (19) Entertainment One (3) Environmental (1) Erotic (16) Eureka Entertainment (18) EuroArts (8) Exploitation (8) Fairy Tales (3) Family (34) Fan Service (2) Fantasy (96) Foreign (117) Fox Searchlight (9) French Language (22) French New Wave (8) Funimation (65) Fusecon (1) FX (1) German Language (1) Gospel/Christian Contemporary (1) 2 of 22 1/4/2012 2:20 PM Blu-rayDefinition.com » X — The Unheard Music: Silver Edition Blu-ray.. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

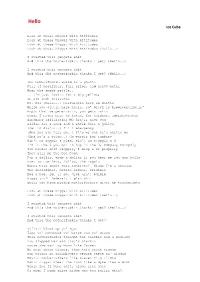

Ice Cube Hello

Hello Ice Cube Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes {Hello..} I started this gangsta shit And this the motherfuckin thanks I get? {Hello..} I started this gangsta shit And this the motherfuckin thanks I get? {Hello..} The motherfuckin world is a ghetto Full of magazines, full clips, and heavy metal When the smoke settle.. .. I'm just lookin for a big yellow; in six inch stilletos Dr. Dre {Hello..} perculatin keep em waitin While you sittin here hatin, yo' bitch is hyperventilatin' Hopin that we penetratin, you gets natin cause I never been to Satan, for hardcore administratin Gangbang affiliatin; MC Ren'll have you wildin off a zone and a whole half a gallon {Get to dialin..} 9 1 1 emergency {And you can tell em..} It's my son he's hurtin me {And he's a felon..} On parole for robbery Ain't no coppin a plea, ain't no stoppin a G I'm in the 6 you got to hop in the 3, company monopoly You handle shit sloppily I drop a ki properly They call me the Don Dada Pop a collar, drop a dollar if you hear me you can holla Even rottweilers, follow, the Impala Wanna talk about this concrete? Nigga I'm a scholar The incredible, hetero-sexual, credible Beg a hoe, let it go, dick ain't edible Nigga ain't federal, I plan shit while you hand picked motherfuckers givin up transcripts Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes Look at these Niggaz With Attitudes {Hello..} I started this gangsta shit And this the motherfuckin thanks I get? {Hello..} I started -

Cypress Hill the Hip-Hop Pioneers Are Back in Business and Ready to Rock

MARCH/APRIL 2010 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM SPOTLIGHT James Minchin sen dog and B-real cypress hill The hip-hop pioneers are back in business and ready to rock Cypress Hill didn’t intend to wait more than a million records. its 1993 hit so long between albums, but the pioneering “insane in the Brain” crossed over to the pop los angeles rap group had some business top 20. Milestones like these have helped to attend to between 2004’s Till Death Do Cypress Hill make an indelible influence Us Part and the new Rise Up. among other on hip-hop’s new generation. “when other things, the foursome toured abroad, worked artists tell you, ‘i started rhyming because on solo projects, changed management of you,’ or ‘i started dJing because of you,’ and switched record labels. “we revamped that’s when it means something to me,” everything, and it took longer than we thought sen dog says. “that’s when i pay attention. it would,” says sen dog. “luckily we came that’s when i think, ‘oK, we have done out the other side ready to release a new something important.’” album and take on the world again.” on Rise Up, the band, which since Rise Up features an array of high-profile 1994 has also included percussionist guests, including singer Marc anthony eric Bobo, was more concerned with and guitar heroes slash and tom Morello. re-establishing itself as a musical force. the “there’s a lot of people, especially rock songs came easily—so easily, in fact, that it ’n’ roll people, that want to get down with took the group by surprise. -

Brand New Deja Entendu Torrent

Brand new deja entendu torrent Continue DOWNLOAD - ��▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀Band........................... Brand NewAlbum............... Deja EntenduYear............................ 2003Genre................... Indie rock, emo, quality . MP3 192 kbit/sArchive file............. rar and .zipCountry................... The United Stateslanguage ............ EnglishOffic site.. TautouSic Transit Gloria Glory FadesI will play my game under the spin lightOkay I believe you, But my Tommy Gun Don't The Silent Things That No One Never KnowThe Boy Who Blocked His Own ShotJaws Theme SwimmingMe vs. Maradona vs. ElvisGuernicaGood know that if I ever need the attention all I have to do is DiePlay Crack Sky Huge thanks to Justin for requesting this group who just turned out to be the perfect band to make this blog 100th post. So, without further ado, I give you the best band ever, Brand New. Thanks to Shadman and Nick for their help with this post as well. Brand New is from Long Island, New York, and was formed in 2000. This group had their roots in another group called Rookie Lot, which three Long Island kids named Jesse Lacey, Garrett Tierney, and Brian Lane were in, along with two other members (who eventually join Crime in Stereo and Movielife respectively). The three remaining members, along with the addition of Vin Accardi (formerly One Last Goodbye), came together to form a new group. Vuala, Brand New. After several demos, they put out their debut in 2001 on Triple Crown Records. At this time they wrote catchy pop-punk songs full of teenage bitterness (well). Their next release, Deja Entendu, showed their maturation as a band and reaching a much larger audience.