Abstract Jordan III, Augustus W. B.S. Florida A&M University, 1994 A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fine Art of Rap Author(S): Richard Shusterman Source: New Literary History, Vol

The Fine Art of Rap Author(s): Richard Shusterman Source: New Literary History, Vol. 22, No. 3, Undermining Subjects (Summer, 1991), pp. 613- 632 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/469207 Accessed: 30/11/2009 16:24 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=jhup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to New Literary History. http://www.jstor.org The Fine Art of Rap Richard Shusterman ... rapt Poesy, And arts, though unimagined, yet to be. -

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

Barber Middle School Accelerated Reader Quiz List Book Interest Quiz No

BARBER MIDDLE SCHOOL ACCELERATED READER QUIZ LIST BOOK INTEREST QUIZ NO. TITLE AUTHOR LEVEL LEVEL POINTS 124151 13 Brown, Jason Robert 4.1 MG 5.0 87689 47 Mosley, Walter 5.3 MG 8.0 5976 1984 Orwell, George 8.9 UG 17.0 78958 (Short) Story of My Life, The Jones, Jennifer B. 4.0 MG 3.0 77482 ¡Béisbol! Latino Baseball Pioneers and Legends (English) Winter, Jonah 5.6 LG 1.0 9611 ¡Lo encontramos debajo del fregadero! Stine, R.L. 3.1 MG 2.0 9625 ¡No bajes al sótano! Stine, R.L. 3.9 MG 3.0 69346 100 Artists Who Changed the World Krystal, Barbara 9.7 UG 9.0 69347 100 Leaders Who Changed the World Paparchontis, Kathleen 9.8 UG 9.0 69348 100 Military Leaders Who Changed the World Crompton, Samuel Willard 9.1 UG 9.0 122464 121 Express Polak, Monique 4.2 MG 2.0 74604 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and Ecstasy of Being Thirteen Howe, James 5.0 MG 9.0 53617 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Grace/Bruchac 7.1 MG 1.0 66779 17: A Novel in Prose Poems Rosenberg, Liz 5.0 UG 4.0 80002 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East Nye, Naomi Shihab 5.8 UG 2.0 44511 1900-10: New Ways of Seeing Gaff, Jackie 7.7 MG 1.0 53513 1900-20: Linen & Lace Mee, Sue 7.3 MG 1.0 56505 1900-20: New Horizons (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 8.4 MG 1.0 62439 1900-20: Print to Pictures Parker, Steve 7.3 MG 1.0 44512 1910-20: The Birth of Abstract Art Gaff, Jackie 7.6 MG 1.0 44513 1920-40: Realism and Surrealism Gaff, Jackie 8.3 MG 1.0 44514 1940-60: Emotion and Expression Gaff, Jackie 7.9 MG 1.0 36116 1940s from World War II to Jackie Robinson, The Feinstein, Stephen 8.3 -

BRE CONFERENCE '90 UPDATE! Columbia " 01\ TENTS

BRE CONFERENCE '90 UPDATE! Columbia " 01\ TENTS MAY 18. 1990 VOLUME XV. NUMBER 18 Publisher SIDNEY MILLER Assistant Publisher SUSAN MILLER Editor -in -Chief RUTH ADKINS ROBINSON Managing Editor JOSEPH ROLAND REYNOLDS FEATURES International Editor COVER STORY-BBD 14 DOTUN ADEBAYO STARTALK-The Winans 45 VP/Midwest Editor DOWNLINK 31 JEROME SIMMONS SECTIONS Art Department PUBLISHERS 5 LANCE VANTILE WHITFIELD art director NEWS 6 MARTIN BLACKWELL MUSIC REPORT 8 typography/computers MUSIC REVIEWS 11 Columnists RADIO NEWS 32 LARRIANN FLORES CONCERT REVIEW SPIDER HARRISON 42 JONATHAN KING JAZZ NOTES 43 ALAN LEIGH GRAPEVINE/PROPHET 46 NORMAN RICHMOND CHARTS & RESEARCH TIM SMITH NEW RELEASE CHART 17 ELAINE STEPTER RADIO REPORT 29 Concert/Record Reviews SINGLES CHART LARRIANN FLORES 34 ELAINE STEPTER THE NATIONAL ADDS 37 Reporters PROGRAMMER'S POLL 36 CORNELIUS GRANT JAZZ CHART 43 COY OAKES ALBUMS CHART 44 LANSING SEBASTIAN COLUMNS RACHEL WILLIAMS RAP, ROOTS & REGGAE 10 Production WHATEVER HAPPENED TO? 12 MAXINE CHONG-MORROW GOSPEL LYNETTE JONES 13 FAR EAST PERSPECTIVE Administration 18 ROXANNE POWELL. office mgr. BRITISH INVASION 19 FELIX WHYTE traffic CANADIAN REPORT 20 Media Relations MICHELE ELYZABETH ENT. (213) 276-1067 Printing PRINTING SERVICES. INC. BLACK RADIO EXCLUSIVE USPS 363-210 ISSN 0745-5992 is published by Black Radio Exclusive 6353 Hollywood Blvd.. Hollywood. CA 90028-6363 (2131469-7262 FAX# 213-469-4121 ' MODEM: 213-469-9172 BRE NEWSSTANDS-New York: Penn Book Store. (2121564-6033; Midwest: Ingram Periodicals; Los Angeles: World Book & News; Robertson News & Bookstore. Las Palmas Newsstand. Japan: Tower Records SUBSCRIPTION RATES: 3 Mos.-$90.6 Mos.-5120:9 Mos.-0150. 1 Yr.-S175: 1st Class -$250: Overseas -$250. -

Boater 133 Final Draft 091018

The Boater Issue 133 May-Aug 2018 The Boater - Issue 133 - Bumper Edition Editor: Jane Percival (Content) Dep. Editor: Mike Phillips (Layout, Artwork) Front & Back Covers: Peter Scrutton Contents 1. Contents 2. TVBC Calendar 3. Welcome Aboard 4. Club News Section 4. Clewer Island BBQ in aid of “MOMENTUM” 6. New Members and Boats 8. Fitting Out Supper& Awards 12. Beale Park Boat Show 17. TVBC Social Evening at ‘The Bells’ 18. Royal Swan Upping + “Nesta” Part Two 28. The First Ever Trad Rally 31. The Day the Rally Died 33. The Trophy Winners at the TTBF 2018 34. The 40th Thames Traditional Boat Festival 36 TTBF Photos from Amersham Photo Society 40. Featured Boat: “Lady Emma” 48. The Voyage of “Lamara” - Part 1 51. Thames Yards revisited - Thornycroft 55. Crossword no.75 56. The Big Picture Advertisers 5. Momentum (Charity) 11. HSC & Saxon Moorings 27. Henwood & Dean 27. River Thames News 38. Tim O’Keefe 47. Stanley & Thomas Back Cover: Classic Restoration Services Cover Picture: “Lady Emma” with boatbuilder Colin Henwood at the helm of his beautiful restoration (Full article p.40). Photo Credits-pages: 4,5 Jane Percival: 9,10 John Llewellyn: 6,7 Photos supplied by owners past & present: 24(L), 25, 31,32 Mike Phillips: 48-50: Ed White 51-54 John Llewellyn. Other photo credits are with the article. The Editor welcomes contributions to ‘The Boater’, which should be Emailed to: Jane Percival: - [email protected] For details on how to send photos, see page 3 1 The Boater Issue 133 May-Aug 2018 TVBC Calendar for 2018-2019 NOTE: Unless marked otherwise, contact Theresa, the Hon Secretary, for details [email protected] July 2018: Weds 4th-Sun 8th : Henley Royal Regatta Mon 16th to Fri 20th : Royal Swan Upping: TVBC boats provide the towing (organiser: Colin Patrick - contact [email protected] ) Fri 20th to Sun 22ⁿd : The Thames Traditional Boat Festival, Henley. -

Music 18145 Songs, 119.5 Days, 75.69 GB

Music 18145 songs, 119.5 days, 75.69 GB Name Time Album Artist Interlude 0:13 Second Semester (The Essentials Part ... A-Trak Back & Forth (Mr. Lee's Club Mix) 4:31 MTV Party To Go Vol. 6 Aaliyah It's Gonna Be Alright 5:34 Boomerang Aaron Hall Feat. Charlie Wilson Please Come Home For Christmas 2:52 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Holy Night 4:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Christmas Song 4:20 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! 2:22 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville White Christmas 4:48 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Such A Night 3:24 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Little Town Of Bethlehem 3:56 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Silent Night 4:06 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Louisiana Christmas Day 3:40 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Star Carol 2:13 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Bells Of St. Mary's 2:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:42 Billboard Top R&B 1967 Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:41 Classic Soul Ballads: Lovin' You (Disc 2) Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven 4:38 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville I Owe You One 5:33 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Don't Fall Apart On Me Tonight 4:24 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville My Brother, My Brother 4:59 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Betcha By Golly, Wow 3:56 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Song Of Bernadette 4:04 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville You Never Can Tell 2:54 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Bells 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville These Foolish Things 4:23 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Roadie Song 4:41 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Ain't No Way 5:01 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Grand Tour 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Lord's Prayer 1:58 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:43 Smooth Grooves: The 60s, Volume 3 L.. -

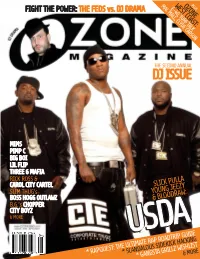

Dj Issue Can’T Explain Just What Attracts Me to This Dirty Game

MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS E-40, TURF TALK OZONE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE OZONE FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE CAN’T EXPLAIN JUST WHAT ATTRACTS ME TO THIS DIRTY GAME ME TO ATTRACTS JUST WHAT MIMS PIMP C BIG BOI LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA RICK ROSS & CAROL CITY CARTEL SLICK PULLA SLIM THUG’s YOUNG JEEZY BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ & BLOODRAW: B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ & MORE APRIL 2007 USDAUSDAUSDA * SCANDALOUS SIDEKICK HACKING * RAPQUEST: THE ULTIMATE* GANGSTA RAP GRILLZ ROADTRIP &WISHLIST MORE GUIDE MAC MALL,WEST CLYDEOZONE COAST:CARSONPLUS REAL, RAW, & UNCENSORED SOUTHERN RAP E-40, TURF TALK FIGHT THE POWER: THE FEDS vs. DJ DRAMA THE SECOND ANNUAL DJ ISSUE MIMS PIMP C LIL FLIP THREE 6 MAFIA & THE SLIM THUG’s BOSS HOGG OUTLAWZ BIG BOI & PURPLE RIBBON RICK ROSS B.G.’s CHOPPER CITY BOYZ YOUNG JEEZY’s USDA CAROL CITY & MORE CARTEL* RAPQUEST: THE* SCANDALOUS ULTIMATE RAP SIDEKICK ROADTRIP& HACKING MORE GUIDE * GANGSTA GRILLZ WISHLIST OZONE MAG // 11 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER // N. Ali Early MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric Perrin ART DIRECTOR // Tene Gooden ADVERTISING SALES // Che’ Johnson PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul MARKETING DIRECTOR // David Muhammad LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Destine Cajuste ADMINISTRATIVE // Cordice Gardner, Kisha Smith CONTRIBUTORS // Alexander Cannon, Bogan, Carlton Wade, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, E-Feezy, Edward Hall, Felita Knight, Iisha Hillmon, Jacinta Howard, Jaro Vacek, Jessica INTERVIEWS Koslow, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jo Jo, Joey Columbo, Johnny Louis, Kamikaze, Keadron Smith, Keith Kennedy, Kenneth Brewer, K.G. -

A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Pace Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2011 No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson Jr. Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Horace E. Anderson, Jr., No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us, 20 Tex. Intell. Prop. L.J. 115 (2011), http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty/818/. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. No Bitin' Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson, Jr: I. History and Purpose of Copyright Act's Regulation of Copying ..................................................................................... 119 II. Impact of Technology ................................................................... 126 A. The Act of Copying and Attitudes Toward Copying ........... 126 B. Suggestions from the Literature for Bridging the Gap ......... 127 III. Potential Influence of Norms-Based Approaches to Regulation of Copying ................................................................. 129 IV. The Hip-Hop Imitation Paradigm ............................................... -

Hoosier Teachers Badly Need Pay Raise, Says~!Aculty Union

Hoosier teachers badly need pay raise, says~!aculty union By Rkk CalU W i The newsletter said that al of political science and former pea- widening hfcGmvar « to * IUPUI'i faculty umuqj^r thcal though union members understand sident of Local 3990 said that since ^Jd cC aevae said that a dm ads of are tear tabs 1990 of the American Federation of 1967 the average purchamng power salary dippagt has put IU tael Teachers, u y t that Hoosier teach the legislature last year because of of teachers m Indiana has de- among the Big Ten m faculty talar* ers badly need a raise in their salar thejrim economic predictions for creased by 20| ies is they are to keep up with the Indiana* state budget He added that while die salaries He said that this la I increasing cost of living But they see no reason not to on non-agricultural A newsletter released by the un give faculty members a much lar ion last month said the 3 5 percent ger salary increase now that the ec ahead of the consumer price inde* sector to RJPUI and is average salary increase expected onomy has substantially improv in the leal 10 years, the marg this year is far below that which is ed average faculty itfvenu actually needed Patrick J McGeever. professor IU School of Nursing celebrates anniversary By Aubrey M. Woods • A May 13 Nursing Recogru The IU School of Nursing has non Ceremony. planned serveral events to com In addition, two awards named memorate its 70th anniversary this for the current Dean of the School year. -

A Stylistic Analysis of 2Pac Shakur's Rap Lyrics: in the Perpspective of Paul Grice's Theory of Implicature

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature Christopher Darnell Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Christopher Darnell, "A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2130. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2130 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: English Composition by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 Approved.by: 7=12 Date Bruce Golden, English ABSTRACT 2pac Shakur (a.k.a Makaveli) was a prolific rapper, poet, revolutionary, and thug. His lyrics were bold, unconventional, truthful, controversial, metaphorical and vulgar. -

Hip-Hop & the Global Imprint of a Black Cultural Form

Hip-Hop & the Global Imprint of a Black Cultural Form Marcyliena Morgan & Dionne Bennett To me, hip-hop says, “Come as you are.” We are a family. Hip-hop is the voice of this generation. It has become a powerful force. Hip-hop binds all of these people, all of these nationalities, all over the world together. Hip-hop is a family so everybody has got to pitch in. East, west, north or south–we come MARCYLIENA MORGAN is from one coast and that coast was Africa. Professor of African and African –dj Kool Herc American Studies at Harvard Uni- versity. Her publications include Through hip-hop, we are trying to ½nd out who we Language, Discourse and Power in are, what we are. That’s what black people in Amer- African American Culture (2002), ica did. The Real Hiphop: Battling for Knowl- –mc Yan1 edge, Power, and Respect in the LA Underground (2009), and “Hip- hop and Race: Blackness, Lan- It is nearly impossible to travel the world without guage, and Creativity” (with encountering instances of hip-hop music and cul- Dawn-Elissa Fischer), in Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century ture. Hip-hop is the distinctive graf½ti lettering (ed. Hazel Rose Markus and styles that have materialized on walls worldwide. Paula M.L. Moya, 2010). It is the latest dance moves that young people per- form on streets and dirt roads. It is the bass beats DIONNE BENNETT is an Assis- mc tant Professor of African Ameri- and styles of dress at dance clubs. It is local s can Studies at Loyola Marymount on microphones with hands raised and moving to University. -

702 Steelo Remixes Mp3, Flac, Wma

702 Steelo Remixes mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop / Funk / Soul Album: Steelo Remixes Country: US Released: 1996 Style: RnB/Swing, Rhythm & Blues MP3 version RAR size: 1451 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1821 mb WMA version RAR size: 1114 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 729 Other Formats: AA MP4 AHX AC3 AU XM MMF Tracklist Hide Credits Steelo (J-Dub Mix Edit) 1 4:00 Co-producer – Kenny BurnsFeaturing – Brad Dacus, Missy ElliottProducer – Dent*, J-Dub* Steelo (Timbaland Mix Edit) 2 4:03 Featuring – Missy ElliottProducer – Timbaland Steelo (Cali Mix) 3 4:09 Producer – Timbaland Steelo (Rashad Remix) 4 Arranged By – Missy Elliott, Rashad SmithCo-producer – Armando ColonProducer – Rashad 3:31 SmithWritten By – Missy Elliott, Rashad Smith Steelo (LP Edit) 5 Featuring – Missy ElliottProducer – Chad "Dr. Ceuss" Elliott*, George PearsonWritten By – 4:00 Chad Elliott, George Pearson, Gordon Sumners* Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Motown Record Company, L.P. Marketed By – Motown Record Company, L.P. Copyright (c) – Biv Ten Records Phonographic Copyright (p) – Biv Ten Records Credits A&R – Derek "Chuck Bone" Osorio*, Todd "Bozak" Russaw* Administrator – Steve Cook Executive Producer – Michael Bivins, Todd Russaw Management – Andre Harrell Notes LP Version appears on the 702 "No Doubt" Vinyl, CD & Cassette 314530738-1/2/4 Steelo contains a sample from "Voices Inside My Head" written by Gordon Sumner ©℗ 1996 Biv Ten Records, a Joint Venture of Motown Record Company, L.P., and Biv Ventures, Inc. Manufactured and Marketed by Motown Record Company, L.P., 825 8th Ave., New York, NY 10019- USA. All Rights Reserved. Unauthorized duplication is a violation of applicable laws.