Twelve-Tone Technique and Modality in Nikos Skalkottas's Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

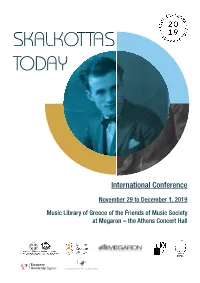

SKALKOTTAS Program 148X21

International Conference Program NOVEMBER 29 TO DECEMBER 1, 2019 Music Library of Greece of the Friends of Music Society at Megaron – the Athens Concert Hall Organised by the Music Library of Greece “Lilian Voudouri” of the Friends of Music Society, Megaron—The Athens Concert Hall, Athens State Orchestra, Greek Composer’s Union, Foundation of Emilios Chourmouzios—Marika Papaioannou, and European University of Cyprus. With the support of the Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Directorate of Modern Cultural Heritage The conference is held under the auspices of the International Musicological Society (IMS) and the Hellenic Musicological Society It is with great pleasure and anticipa- compositional technique. This confer- tion that this conference is taking place ence will give a chance to musicolo- Organizing Committee: Foreword .................................... 3 in the context of “2019 - Skalkottas gists and musicians to present their Thanassis Apostolopoulos Year”. The conference is dedicated to research on Skalkottas and his environ- the life and works of Nikos Skalkottas ment. It is also happening Today, one Alexandros Charkiolakis Schedule .................................... 4 (1904-1949), one of the most important year after the Aimilios Chourmouzios- Titos Gouvelis Greek composers of the twentieth cen- Marika Papaioannou Foundation depos- tury, on the occasion of the 70th anni- ited the composer’s archive at the Music Petros Fragistas Abstracts .................................... 9 versary of his death and the deposition Library of Greece “Lilian Voudouri” of Vera Kriezi of his Archive at the Music Library of The Friends of Music Society to keep Greece “Lilian Voudouri” of The Friends safe, document and make it available for Martin Krithara Biographies ............................. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1984, Tanglewood

m~ p. - . i j- fjffii V .*& - "lli s -» «*: W . mr jrr~r *hi W **VtitH°** "Bk . Less than a mile from Tanglewood . White Pines offers all of the carefree convenience of condominium living in truly luxurious contemporary in- White teriors. The White Pines buildings, four-season swimming pool, Har-Tru tennis courts and private beach on Stockbridge Bowl are all set in the Pines magnificence of a traditional French Provincial country estate. $180,000 country estate and up. Our model is open seven days a week. condominiums at Stockbridge P. O. Box 949 Dept. T Hawthorne St. Stockbridge MA 01262 (413)637-1140 or Reinholt Realty. Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Sir Colin Davis, Principal Guest Conductor Joseph Silverstein, Assistant Conductor One Hundred and Third Season, 1983-84 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Leo L. Beranek, Chairman Nelson J. Darling, Jr., President Mrs. Harris Fahnestock, Vice-President George H. Kidder, Vice-President Sidney Stoneman, Vice-President Roderick M. MacDougall, Treasurer John Ex Rodgers, Assistant Treasurer Vernon R. Alden Mrs. Michael H. Davis Thomas D. Perry, Jr. David B. Arnold, Jr. Archie C. Epps III William J. Poorvu J.R Barger Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick Irving W. Rabb Mrs. John M. Bradley Mrs. John L. Grandin Mrs. George R. Rowland Mrs. Norman L. Cahners E. James Morton Mrs. George Lee Sargent George H.A. Clowes, Jr. David G. Mugar William A. Selke Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney Albert L. Nickerson John Hoyt Stookey Trustees Emeriti Abram T. Collier, Chairman of the Board Emeritus Philip K. Allen E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Mrs. -

Download Booklet

BIS-CD-I024STEREO IED D] Total playing time: 65'39 SKALKOTTAS, Nikos 0eo4-ts4s) Sonata for Solo Violin (tszs) (MaryunMusic) 12'48 tr L Allegrofurioso, quasi Presto 2'.33 tr 11.Adagietto z',42 tr Ill. Allegro ritmctto t'4r tr IY. Adagio - Allegro molto Moderato 5'40 Sonatina No. I for Violin and Piano (1929)rvo E II. Andantino 2'50 Sonatina No.2 for Violin and Piano 119291rvr,r 6',42 tr I. Allegro 2',13 tr II. Andante 2'20 tr IlL Allegro vivac:e 2',01 Sonatina No.3 for Piano and Violin (ts:s) (MarsunMusic) 11,28 tr I. Allegro giusto 2',55 @ II. Andante 5'06 E I1l. Maestoso - Vivace 3',11 Sonatina No.4 for Piano and Violin (l935) @aryunMusic) 13'13 tr I. Moderatr.t 3'26 Llg Il. Adagio 6',49 [4 1ll. Allegro moderato 2',51 Little Chorale and Fugue (c.1936131?)(MaryunMusic) z',56 E Adasio 1'16 @ Moderato 1'40 tr March of the Little Soldiers (c.193613'7?)(MaryilnMusic) 0'50 Moderato ritmato E Nocturne (c.1936137?) (MarsunMusit) 4',53 Andante @ Rondo (c.1936137?) tMaryunMusic) 1'18 Allegro deciso @ Gavotte (1939)rup 1'36 Bienmodtrl E Scherzo1c. l94o?r 'w., )t)1 Allegro molto vivace @ Menuetto Cantato (c.l94o'!)rurt z',14 Molto moderato - Trio Georgios Demertzis,violin Maria Asteriadou, piano INSTRUMENTARIUM Violin:Johannes Cuypers l80l GrandPiano: Steinway D Pianotechnician: Osten Haggmark Nikos Skalkottas: A brief biography evolution as a composer follows certain invariable axes Nikos Skalkottas was bom in Halkis in 190,1 and died in that denne his confrontation with the historical, technical Athens in 1949. -

Download Booklet

BIS-CD-1384 Skalkottas 11/10/05 10:42 AM Page 2 SKALKOTTAS, Nikos (1904-1949) The Sea, Ballett Suite (1948-49) (Schirmer [orchestral parts by Byron Fidetzis]) 45'15 1 I. Prelude. Moderato maestoso 4'56 2 II.The Child of the Sea. Andantino 3'01 3 III. Dance of the Waves. Allegro molto vivace 3'00 4 IV. The Trawler. Moderato andante 3'30 5 V. The Little Fish. Allegretto grazioso 2'15 6 VI. The Dolphins. Allegro (molto) poco scherzoso 5'04 7 VII. Nocturne. Andante molto – Calmo erpressivo 4'53 8 VIII. Preparation of the Mermaid. Moderato sostenuto 2'36 9 IX. Dance of the Mermaid. Allegro molto vivace (furioso) 2'31 10 X. The Story of Alexander the Great 7'36 11 XI. Finale. Hymn to the Sea 4'42 Allegro vivace, Poco maestoso, poco calmo e alla breve Four Images (1948) (Skalkottas Academy Edition) 13'43 12 I. The harvest. Moderato 3'21 13 II. The seeding. Andante 5'01 14 III. The wintage. Allegro 2'42 15 IV. The wine-press. Molto vivace 2'27 MITROPOULOS, Dimitris (1896-1960), orchestrated by Nikos Skalkottas 16 Cretian Feast (Fête crétois) (1919, orch. 1923/24) (Manuscript) 7'20 SKALKOTTAS, Nikos (1904-1949) 17 Greek Dance in C minor (1949?) (Manuscript) 5'07 TT: 72'44 Iceland Symphony Orchestra Gu-dn´y Gu-dmundsdóttir leader Byron Fidetzis conductor 2 Nikos Skalkottas and the Greek Traditions It has become conventional to make reference to the decisive point in Skalkottas's life marked by his final return to Greece in 1933. -

2017–2018 SEASON Markand Thakar Music Director President’S Welcome!

ravo! 2017–2018 SEASON markand thakar music director president’s welcome! Welcome to Baltimore Chamber Orchestra’s 2017–2018 season: BCO’s 35th year. We are delighted to bring you five concerts again this season! Welcome to Baltimore Chamber Orchestra’s 2017–2018 season: BCO’s 35th year! We are delighted to bring you once again five outstanding concerts this season! BCO is one of the musical treasures of Baltimore. We provide compelling performances of outstanding music in a comfortable, beautiful setting that's easily accessible. Our specialty is music for smaller orchestral ensembles from the extensive classical canon. BCO provides fresh and inspiring interpretations of familiar classics, as well as an opportunity to hear less well-known masterpieces ignored by larger orchestras. BCO is Baltimore’s Intimate Classical Orchestra, striving to create musical intensity at every performance. Our Sunday afternoon audiences are passionate about our concerts and our strong reviews reflect the artistry of the orchestra. Thank you for your generous financial contributions that enable BCO to present outstanding classical music each season. Ticket revenues provide only a portion of the orchestra's operating budget. Your donations also sustain BCO’s commitment to music education of young people, including All Students Free All the Time at concerts. Live Wire String Quartet, BCO’s educational- outreach ensemble, touched the lives of more than 2,000 students last season. And, this season brings the inauguration of The Listening Lab, BCO’s second music-education project for older, elementary-school students. We are helping to create the next generation of classical music lovers! I would also like to highlight our Music Director Markand Thakar's exciting conducting programs each winter and summer. -

Nikos Skalkottas Piano Concerto No

Nikos Skalkottas Piano Concerto No. 3 Daan Vandewalle Blattwerk Johannes Kalitzke Nikos Skalkottas (1904 – 1949) Concerto for Piano, Ten Wind Instruments and Percussion, AK 18 (1939) 1 Moderato 19:25 2 Andante sostenuto 18:53 3 Allegro giocoso 16:02 Daan Vandewalle, piano Blattwerk Johannes Kalitzke, conductor 3 with Willy Hess in Berlin, but in 1923 he decided to give up his ca- reer as a violinist and instead to become a composer. He studied in Berlin first with Robert Kahn and Philipp Jarnach, then briefly with Kurt Weill, and from 1927 to 1931 with Arnold Schönberg. From his relationship with the Ukrainian violinist Matla Temko (1903 – 1986) came two daughters, only one of whom survived (Artemis Lindal, born in 1927). When her mother separated from Skalkottas in 1931, they moved to Sweden. Although Skalkottas remained in Berlin until 1933, he composed almost nothing in the two years before that and was forced to re- turn to Greece for financial reasons as well as for the increasing- ly limited possibilities of practicing contemporary art in Germany. Almost all his numerous compositions from before 1931 have been lost. Back in Athens, he did not want to work as a composer be- cause he felt misunderstood and played as a violinist in various or- chestras instead. After 1935, he composed again, but without hav- Nikos Skalkottas (1904 – 1949) has remained a “composer for ing his works printed or re-energized. In 1943, he met the pianist musicians” to this day. In other words, most musicians know Maria Pangali, who he married on 15 September 1946. -

![[From the Friends of NIKOS SKALKOTTAS`S Music Society]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5555/from-the-friends-of-nikos-skalkottas-s-music-society-3105555.webp)

[From the Friends of NIKOS SKALKOTTAS`S Music Society]

ΒΙΟGRAPHY OF NIKOS SKALKOTTAS [from The Friends of NIKOS SKALKOTTAS`S Music Society] ΒΙΟGRAPHY OF NIKOS SKALKOTTAS [from The Friends of NIKOS SKALKOTTAS`S Music Society] Nikos Skalkottas was born in Chalkis in 1904 and died in Athens in 1949. Very early on he started violin lessons with his musician father and uncle. He continued studying at the Athens Conservatory and graduated in 1920. From 1921 to 1933 he lived in Berlin, where he first took violin lessons with Willy Hess. In 1923 he decided to give up his career as a violinist and become a composer. He studied compositio n with Paul Kahn, Paul Juon, Kurt Weill, Philipp Jarnach and Arnold Schönberg. In 1933, when Hitler came to power, Skalkottas returned to Athens, where he earned a living playing in different orchestras. Skalkottas’s early works, most of which he wrote in Berlin and some of those written in Athens, are lost. The earliest of his works available to us today are dating from 1922-24 and are piano compositions as well as the orchestration of "Cretan Feast"by Dimitris Mitropoulos. Among the later works written in Berlin are the sonata for solo violin, several works for piano, chamber music and some symphonic works. During the period 1931- 1934 Skalkottas did not compose anything. He started composing again in Athens continued until he died. His works comprise symphonic works ( Greek Dances, The symphonic overture Return of Ulysses, The fairy drama Mayday Spell, The second symphonic suite, the ballet The Maiden and Death, The Classical Symphony for winds, a Sinfonietta and several concertos ), Chamber music works, as well as vocal works and music pieces for solo instrument. -

SKALKOTTAS, Nikos (1904-1949)

BIS-CD-1244 STEREO D D D Total playing time: 79'26 SKALKOTTAS, Nikos (1904-1949) Concerto for Two Violins (Skalkottas Archive, M/s) WORLD PREMIÈRE RECORDING 34'37 (with ‘Rembetiko’ theme) (1944-45) 1 I. Allegro giocoso 12'29 2 II. Variations sur un thème grec Rembetiko. Andante 11'54 3 III. Finale and Rondo. Allegro molto vivace 10'00 Eiichi Chijiiwa and Nina Zymbalist, violins; Nikolaos Samaltanos and Christophe Sirodeau, piano Works for Wind Instruments and Piano (1939-43) (Schirmer [ex-Margun Music] & M/s) Quartet for Oboe, Trumpet, Bassoon and Piano 3'19 4 I. Moderato assai 2'05 5 II. Rondo. Vivace 1'13 Alexeï Ogrintchouk, oboe; Eric Aubier, trumpet; Marc Trenel, bassoon; Nikolaos Samaltanos, piano Concertino for Oboe and Piano 10'35 6 I. Allegro giocoso 4'25 7 II. Pastorale. Andante tranquillo 4'23 8 III. Rondo. Allegro vivo 1'43 Alexeï Ogrintchouk, oboe; Nikolaos Samaltanos, piano 2 9 Concertino for Trumpet and Piano 4'41 Allegro giusto (alla breve) Eric Aubier, trumpet; Nikolaos Samaltanos, piano Tango and Fox-trot for Oboe, Trumpet, Bassoon and Piano 3'59 10 Tango. Tempo di Tango 1'22 11 Fox-trot. Allegro ritmato 1'37 Alexeï Ogrintchouk, oboe; Eric Aubier, trumpet; Marc Trenel, bassoon; Nikolaos Samaltanos, piano Sonata Concertante for Bassoon and Piano 21'43 12 I. Allegro molto vivace 8'10 13 II. Andantino 8'17 14 III. Presto 5'07 Marc Trenel, bassoon; Nikolaos Samaltanos, piano INSTRUMENTARIUM Grand piano: Fazioli, No. 2780649. Piano technician: Jean-Michel Daudon Violin 1 (Eiichi Chijiiwa): Omobono Stradivari 1740, ‘Freiche’. -

The Houston Sinfonietta

The Hellenic Professional Society of Texas in cooperation with The Shepherd School of Music Presents The Houston Sinfonietta Hamman Hall Rice University Sunday, january 22, 1989, 3:00p.m. • PROGRAM Aaron Copland Fanfare for the Common Man Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 40 in G-minor Allep,ro Molto Ancfante Menuetto Allegro Assai Intermission Ernest Chausson Poeme for Violin and Orchestra Susan Chester, Soloist Nikos Skalkottas Four Greek Dances Tsamikos Cretikos Peloponesiakos Epirotikos The Houston Sinfonietta Conductor: George Blytas Violins Flutes Richard Baum, Concertmaster Evan Bauman Tina Blytas Heather Berkley Marcile Carbone Kelly Kimball Susan Chester Annette Lott Stephanie Coxe Carolyn Harkins Oboes Mary Hawthorn john Helton julie jacobs Mitzi jones Ron Rothman john MacBain Betsy Mims Clarinets David Mitchell jacob Sh lyapobersky Diedre Horne Bob Szentinnay Mary Thro Mary Uhrbrock Oscar Wehmanen Bassoons Violas Betty frederick Bob Hawthorn Andrew Havely Michael Jones French Horns Todd McCall Howard Williams Sylvia Crafton joe Frantz Cellos Miriam Herrera Lorena Unger Mike Allexander Taki Blytas Trumpets Joanne Hildebrand Plia Preston Carl Goshy Randy Whitford Eric Kurry George Robinson Warren Loomis Bass Trombones Brett Gensler Mark Andrews Reginald Berry Percussion Boo Storey Bill Nail Tuba Monica Szopa jack Westmoreland Tommy Tuggle Harp Debbie O'Donnel Notes about the Composers Aaron Copland (1900- ) is one of the most influential American composers. He was tile first of several Americans to study in Paris with Nadia Boulanger. Copland drew on elements of jazz, New England hymns and folk songs to acheive a uniquely American musical style. His Fanfare for the Common Man, for brass and percussion, was composed in 1942, during World War II. -

The Army, the Airwaves, and the Avant-Garde: American Classical Music in Postwar West Germany Author(S): Amy C

The Army, the Airwaves, and the Avant-Garde: American Classical Music in Postwar West Germany Author(s): Amy C. Beal Source: American Music, Vol. 21, No. 4 (Winter, 2003), pp. 474-513 Published by: University of Illinois Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3250575 Accessed: 22/11/2010 15:44 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=illinois. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Illinois Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Music. http://www.jstor.org AMY C. BEAL The Army, the Airwaves, and the Avant-Garde: American Classical Music in Postwar West Germany Music Most Worthy-At the Office of War Information Even before World War II ended, American composers helped plan for the dissemination of American culture in postwar Europe. -

JAVS 29.1.Pdf

Features: Rossini’s Viola Solos Nadia Sirota and Nico Muhly Performance Practice Issues in Harold in Italy Volume 29 Volume Number 1 Tabuteau’s Journal of Journal the American Viola Society Number System Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Spring 2013 Volume 29 Number 1 Contents p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President p. 7 News & Notes: In Memoriam ~ IVC Host Letter Feature Articles p. 11 A Double-Barreled Rossinian Viola Story: Carlos María Solare discovers two Rossini viola solos during his visit to the 2012 Rossini Opera Festival p. 15 “Meet People and Have a Nice Time”: A Conversation with Nadia Sirota and Nico Muhly: Alexander Overington enjoys good food and conversation with violist Nadia Sirota and composer Nico Muhly p. 25 The Viola in Berlioz’s Harold in Italy: Amanda Wilton, the second-prize winner of the 2012 David Dalton Viola Research Competition, examines performance issues for the solo viola part in Berlioz’s famous symphony p. 33 Forward Motion: Teaching Phrasing using Marcel Tabuteau’s Number System: Joyce Chan, the first-prize winner of the 2012 David Dalton Viola Research Competition, introduces Marcel Tabuteau’s number system and its application to standard viola repertoire Departments p. 39 The Eclectic Violist: A look at the world of a worship violist p. 43 Orchestral Training Forum: Learn essentials of opera performing and auditioning from CarlaMaria Rodrigues p. 51 Retrospective: Tom Tatton revisits viola music by Leo Sowerby and Alvin Etler p. 57 Student Life: Meet three young composers who are “rocking the boat” p. -

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings of the Year 2020

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings Of The Year 2020 This is the eighteenth year that MusicWeb International has asked its reviewing team to nominate their recordings of the year. Reviewers are not restricted to discs they had reviewed, but the choices must have been reviewed on MWI in the last 12 months (December 2019-November 2020). The 146 selections have come from 28 members of the team and 69 different labels, the choices reflecting as usual, the great diversity of music and sources; I say that every year, but still the spread of choices surprises and pleases me. Of the selections, ten have received two nominations: • Eugene Ormandy’s Saint-Saëns Organ symphony on Dutton • Choral music by Jančevskis on Hyperion • Stephen Hough’s Beethoven concertos on Hyperion • Lutosławski symphonies on Ondine • Stewart Goodyear’s Beethoven concertos on Orchid Classics • Maria Gritskova’s Prokofiev Songs and Romances on Naxos • Giandrea Noseda’s Dalapiccola Il Priogioniero on Chandos • Les Kapsber'girls Che fai tù? on Muso • Edward Gardner’s Peter Grimes on Chandos • Véronique Gens recital Nuits on Alpha Hyperion was this year’s leading label with 16 nominations, and Chandos with 11 deserves an honourable mention. MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL RECORDING OF THE YEAR In this twelve-month period, we published more than 2300 reviews. There is no easy or entirely satisfactory way of choosing one above all others as our Recording of the Year. Ludwig van BEETHOVEN Piano Concertos 1-5 - Stephen Hough (piano), Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra/Hannu Lintu rec. 2019 HYPERION CDA68291/3 It being a big Beethoven anniversary year, that seemed to provide a clue as to where to look for a choice.