Hans Keller, Nikos Skalkottas and the Notion of Symphonic Genius

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symposium Programme

Singing a Song in a Foreign Land a celebration of music by émigré composers Symposium 21-23 February 2014 and The Eranda Foundation Supported by the Culture Programme of the European Union Royal College of Music, London | www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Follow the project on the RCM website: www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: Symposium Schedule FRIDAY 21 FEBRUARY 10.00am Welcome by Colin Lawson, RCM Director Introduction by Norbert Meyn, project curator & Volker Ahmels, coordinator of the EU funded ESTHER project 10.30-11.30am Session 1. Chair: Norbert Meyn (RCM) Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: The cultural impact on Britain of the “Hitler Émigrés” Daniel Snowman (Institute of Historical Research, University of London) 11.30am Tea & Coffee 12.00-1.30pm Session 2. Chair: Amanda Glauert (RCM) From somebody to nobody overnight – Berthold Goldschmidt’s battle for recognition Bernard Keeffe The Shock of Exile: Hans Keller – the re-making of a Viennese musician Alison Garnham (King’s College, London) Keeping Memories Alive: The story of Anita Lasker-Wallfisch and Peter Wallfisch Volker Ahmels (Festival Verfemte Musik Schwerin) talks to Anita Lasker-Wallfisch 1.30pm Lunch 2.30-4.00pm Session 3. Chair: Daniel Snowman Xenophobia and protectionism: attitudes to the arrival of Austro-German refugee musicians in the UK during the 1930s Erik Levi (Royal Holloway) Elena Gerhardt (1883-1961) – the extraordinary emigration of the Lieder-singer from Leipzig Jutta Raab Hansen “Productive as I never was before”: Robert Kahn in England Steffen Fahl 4.00pm Tea & Coffee 4.30-5.30pm Session 4. -

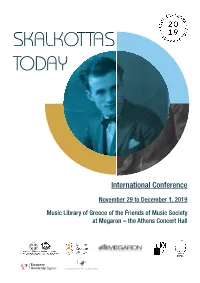

SKALKOTTAS Program 148X21

International Conference Program NOVEMBER 29 TO DECEMBER 1, 2019 Music Library of Greece of the Friends of Music Society at Megaron – the Athens Concert Hall Organised by the Music Library of Greece “Lilian Voudouri” of the Friends of Music Society, Megaron—The Athens Concert Hall, Athens State Orchestra, Greek Composer’s Union, Foundation of Emilios Chourmouzios—Marika Papaioannou, and European University of Cyprus. With the support of the Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Directorate of Modern Cultural Heritage The conference is held under the auspices of the International Musicological Society (IMS) and the Hellenic Musicological Society It is with great pleasure and anticipa- compositional technique. This confer- tion that this conference is taking place ence will give a chance to musicolo- Organizing Committee: Foreword .................................... 3 in the context of “2019 - Skalkottas gists and musicians to present their Thanassis Apostolopoulos Year”. The conference is dedicated to research on Skalkottas and his environ- the life and works of Nikos Skalkottas ment. It is also happening Today, one Alexandros Charkiolakis Schedule .................................... 4 (1904-1949), one of the most important year after the Aimilios Chourmouzios- Titos Gouvelis Greek composers of the twentieth cen- Marika Papaioannou Foundation depos- tury, on the occasion of the 70th anni- ited the composer’s archive at the Music Petros Fragistas Abstracts .................................... 9 versary of his death and the deposition Library of Greece “Lilian Voudouri” of Vera Kriezi of his Archive at the Music Library of The Friends of Music Society to keep Greece “Lilian Voudouri” of The Friends safe, document and make it available for Martin Krithara Biographies ............................. -

Twelve-Tone Technique and Modality in Nikos Skalkottas's Music

IMS-RASMB, Series Musicologica Balcanica 1.1, 2020. e-ISSN: 2654-248X Twelve-tone Technique and Modality in Nikos Skalkottas’s Music by George Zervos DOI: https://doi.org/10.26262/smb.v1i1.7754 ©2020 The Author. This is an open access article under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCom- mercial NoDerivatives International 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the articles is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made. Zervos, Twelve-Tone Technique and Modality… Twelve-Tone Technique and Modality in Nikos Skalkottas’s Music George Zervos Abstract In Nikos Skalkottas’s compositional output, the use of modality through the folk tra- dition, is not limited to some of the tonal works, such as the 36 Greek Dances, but it also extends to the strictly or freely twelve-tone works; indeed, this is the case throughout the composer’s creative life. Given the changing character of the ways in which this folk tradition is incorporated into a twelve-tone and, in general, an atonal environ- ment, we chose two works from different periods, in order to show the modes in which the composer manages to connect the various aspects of the twelve-tone with modal- ity: these are the first movement of Sonatina No.2 for violin and piano (1929), and the first movement of Petite Suite No.1 for solo violin and piano (1946). More specifically, in the first case, we will show the ways in which the prime row is transformed into a diatonic- chromatic-like modality, and in the second case we will discuss the function of the combination of two complementary hexachords through which two sets are produced. -

A Theory of Spatial Acquisition in Twelve-Tone Serial Music

A Theory of Spatial Acquisition in Twelve-Tone Serial Music Ph.D. Dissertation submitted to the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in Music Theory by Michael Kelly 1615 Elkton Pl. Cincinnati, OH 45224 [email protected] B.M. in Music Education, the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music B.M. in Composition, the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music M.M. in Music Theory, the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music Committee: Dr. Miguel Roig-Francoli, Dr. David Carson Berry, Dr. Steven Cahn Abstract This study introduces the concept of spatial acquisition and demonstrates its applicability to the analysis of twelve-tone music. This concept was inspired by Krzysztof Penderecki’s dis- tinctly spatial approach to twelve-tone composition in his Passion According to St. Luke. In the most basic terms, the theory of spatial acquisition is based on an understanding of the cycle of twelve pitch classes as contiguous units rather than discrete points. Utilizing this theory, one can track the gradual acquisition of pitch-class space by a twelve-tone row as each of its member pitch classes appears in succession, noting the patterns that the pitch classes exhibit in the pro- cess in terms of directionality, the creation and filling in of gaps, and the like. The first part of this study is an explanation of spatial acquisition theory, while the se- cond part comprises analyses covering portions of seven varied twelve-tone works. The result of these analyses is a deeper understanding of each twelve-tone row’s composition and how each row’s spatial characteristics are manifested on the musical surface. -

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten Through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Jensen, Joni Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 21:33:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/193556 A COMPARISON OF ORIGINS AND INFLUENCES IN THE MUSIC OF VAUGHAN WILLIAMS AND BRITTEN THROUGH ANALYSIS OF THEIR FESTIVAL TE DEUMS by Joni Lynn Jensen Copyright © Joni Lynn Jensen 2005 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC AND DANCE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 5 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Joni Lynn Jensen entitled A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughan Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Bruce Chamberlain _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Elizabeth Schauer _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Josef Knott Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

An Introduction to Ludwig Van Beethoven

CHANDOS :: intro CHAN 2020 an introduction to Ludwig van Beethoven :: 13 CCHANHAN 22020020 BBook.inddook.indd 112-132-13 330/7/060/7/06 113:10:533:10:53 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) 1 Overture to ‘The Creatures of Prometheus’, Op. 43 5:22 Classical music is inaccessible and diffi cult. Adagio – Allegro molto con brio It’s surprising how many people still believe the above statement to be true, so this new series Piano Concerto No. 5 in E fl at major, from Chandos is not only welcome, it’s also very Op. 73 ‘Emperor’* 39:12 necessary. 2 I Allegro 20:16 I was lucky enough to stumble upon the 3 II Adagio un poco mosso 8:29 wonderful world of the classics when I was a 4 III Rondo. Allegro 10:27 child, and I’ve often contemplated how much poorer my life would have been had I not done so. As you have taken the fi rst step by buying this Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 33:21 CD, I guarantee that you will share the delights 5 I Allegro con brio 8:25 of this epic journey of discovery. Each CD in the 6 II Andante con moto 10:19 series features the orchestral music of a specifi c 7 III Allegro – 5:26 composer, with a selection of his ‘greatest hits’ 8 IV Allegro 9:08 CHANDOS played by top quality performers. It will give you Total time 77:55 a good fl avour of the composer’s style, but you won’t fi nd any nasty surprises – all the music is John Lill piano* instantly accessible and appealing. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1984, Tanglewood

m~ p. - . i j- fjffii V .*& - "lli s -» «*: W . mr jrr~r *hi W **VtitH°** "Bk . Less than a mile from Tanglewood . White Pines offers all of the carefree convenience of condominium living in truly luxurious contemporary in- White teriors. The White Pines buildings, four-season swimming pool, Har-Tru tennis courts and private beach on Stockbridge Bowl are all set in the Pines magnificence of a traditional French Provincial country estate. $180,000 country estate and up. Our model is open seven days a week. condominiums at Stockbridge P. O. Box 949 Dept. T Hawthorne St. Stockbridge MA 01262 (413)637-1140 or Reinholt Realty. Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Sir Colin Davis, Principal Guest Conductor Joseph Silverstein, Assistant Conductor One Hundred and Third Season, 1983-84 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Leo L. Beranek, Chairman Nelson J. Darling, Jr., President Mrs. Harris Fahnestock, Vice-President George H. Kidder, Vice-President Sidney Stoneman, Vice-President Roderick M. MacDougall, Treasurer John Ex Rodgers, Assistant Treasurer Vernon R. Alden Mrs. Michael H. Davis Thomas D. Perry, Jr. David B. Arnold, Jr. Archie C. Epps III William J. Poorvu J.R Barger Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick Irving W. Rabb Mrs. John M. Bradley Mrs. John L. Grandin Mrs. George R. Rowland Mrs. Norman L. Cahners E. James Morton Mrs. George Lee Sargent George H.A. Clowes, Jr. David G. Mugar William A. Selke Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney Albert L. Nickerson John Hoyt Stookey Trustees Emeriti Abram T. Collier, Chairman of the Board Emeritus Philip K. Allen E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Mrs. -

CUL Keller Archive Catalogue

HANS KELLER ARCHIVE: working copy A1: Unpublished manuscripts, 1940-49 A1/1: Unpublished manuscripts, 1940-49: independent work This section contains all Keller’s unpublished manuscripts dating from the 1940s, apart from those connected with his collaboration with Margaret Phillips (see A1/2 below). With the exception of one pocket diary from 1938, the Archive contains no material prior to his arrival in Britain at the end of that year. After his release from internment in 1941, Keller divided himself between musical and psychoanalytical studies. As a violinist, he gained the LRAM teacher’s diploma in April 1943, and was relatively active as an orchestral and chamber-music player. As a writer, however, his principal concern in the first half of the decade was not music, but psychoanalysis. Although the majority of the musical writings listed below are undated, those which are probably from this earlier period are all concerned with the psychology of music. Similarly, the short stories, poems and aphorisms show their author’s interest in psychology. Keller’s notes and reading-lists from this period indicate an exhaustive study of Freudian literature and, from his correspondence with Margaret Phillips, it appears that he did have thoughts of becoming a professional analyst. At he beginning of 1946, however, there was a decisive change in the focus of his work, when music began to replace psychology as his principal subject. It is possible that his first (accidental) hearing of Britten’s Peter Grimes played an important part in this change, and Britten’s music is the subject of several early articles. -

Winner's Recital

19 July 2021 7.30pm Wigmore Hall Guildhall Wigmore Recital Prize Winner’s Recital Élisabeth Pion piano Guildhall School of Music & Drama Wigmore Hall is a no-smoking venue. No Founded in 1880 by the recording or photographic equipment may City of London Corporation be taken into the auditorium, nor used in any other part of the Hall without the prior Chairman of the Board of Governors written permission of the Hall Graham Packham Management. Wigmore Hall is equipped with a ‘Loop’ to help hearing aid users Principal receive clear sound without background Lynne Williams am noise. Patrons can use the facility by Vice-Principal and Director of Music switching their hearing aids over to ‘T’. Professor Jonathan Vaughan In accordance with the requirements of Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk City of Westminster, persons shall not be permitted to stand or sit in any of the gangways intersecting the seating, or to Wigmore Hall sit in any of the other gangways. 36 Wigmore Street, London, W1U 2BP If standing is permitted in the gangways Director at the sides and rear of the seating, it shall John Gilhooly be limited to the numbers indicated in the The Wigmore Hall Trust notices exhibited in those positions. Registered Charity No. 1024838 Facilities for Disabled People: www.wigmore-hall.org.uk For full details please email [email protected] or call 020 7935 2141. Guildhall School is provided by the City of London as part of its contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation. Guildhall Wigmore Recital Prize Winner’s Recital Élisabeth Pion piano Mozart Piano Sonata in F major, K332 Lili Boulanger Prélude in D flat major Lili Boulanger Trois morceaux pour piano Messiaen Le baiser de l’enfant Jésus Ravel Ondine Beethoven Piano Sonata in F minor, Op 57, ‘Appassionata’ (1804–5) Monday 19 July 2021, 7.30pm Wigmore Hall Would patrons please ensure that mobile phones are switched off. -

Download Booklet

BIS-CD-I024STEREO IED D] Total playing time: 65'39 SKALKOTTAS, Nikos 0eo4-ts4s) Sonata for Solo Violin (tszs) (MaryunMusic) 12'48 tr L Allegrofurioso, quasi Presto 2'.33 tr 11.Adagietto z',42 tr Ill. Allegro ritmctto t'4r tr IY. Adagio - Allegro molto Moderato 5'40 Sonatina No. I for Violin and Piano (1929)rvo E II. Andantino 2'50 Sonatina No.2 for Violin and Piano 119291rvr,r 6',42 tr I. Allegro 2',13 tr II. Andante 2'20 tr IlL Allegro vivac:e 2',01 Sonatina No.3 for Piano and Violin (ts:s) (MarsunMusic) 11,28 tr I. Allegro giusto 2',55 @ II. Andante 5'06 E I1l. Maestoso - Vivace 3',11 Sonatina No.4 for Piano and Violin (l935) @aryunMusic) 13'13 tr I. Moderatr.t 3'26 Llg Il. Adagio 6',49 [4 1ll. Allegro moderato 2',51 Little Chorale and Fugue (c.1936131?)(MaryunMusic) z',56 E Adasio 1'16 @ Moderato 1'40 tr March of the Little Soldiers (c.193613'7?)(MaryilnMusic) 0'50 Moderato ritmato E Nocturne (c.1936137?) (MarsunMusit) 4',53 Andante @ Rondo (c.1936137?) tMaryunMusic) 1'18 Allegro deciso @ Gavotte (1939)rup 1'36 Bienmodtrl E Scherzo1c. l94o?r 'w., )t)1 Allegro molto vivace @ Menuetto Cantato (c.l94o'!)rurt z',14 Molto moderato - Trio Georgios Demertzis,violin Maria Asteriadou, piano INSTRUMENTARIUM Violin:Johannes Cuypers l80l GrandPiano: Steinway D Pianotechnician: Osten Haggmark Nikos Skalkottas: A brief biography evolution as a composer follows certain invariable axes Nikos Skalkottas was bom in Halkis in 190,1 and died in that denne his confrontation with the historical, technical Athens in 1949. -

Download Booklet

BIS-CD-1384 Skalkottas 11/10/05 10:42 AM Page 2 SKALKOTTAS, Nikos (1904-1949) The Sea, Ballett Suite (1948-49) (Schirmer [orchestral parts by Byron Fidetzis]) 45'15 1 I. Prelude. Moderato maestoso 4'56 2 II.The Child of the Sea. Andantino 3'01 3 III. Dance of the Waves. Allegro molto vivace 3'00 4 IV. The Trawler. Moderato andante 3'30 5 V. The Little Fish. Allegretto grazioso 2'15 6 VI. The Dolphins. Allegro (molto) poco scherzoso 5'04 7 VII. Nocturne. Andante molto – Calmo erpressivo 4'53 8 VIII. Preparation of the Mermaid. Moderato sostenuto 2'36 9 IX. Dance of the Mermaid. Allegro molto vivace (furioso) 2'31 10 X. The Story of Alexander the Great 7'36 11 XI. Finale. Hymn to the Sea 4'42 Allegro vivace, Poco maestoso, poco calmo e alla breve Four Images (1948) (Skalkottas Academy Edition) 13'43 12 I. The harvest. Moderato 3'21 13 II. The seeding. Andante 5'01 14 III. The wintage. Allegro 2'42 15 IV. The wine-press. Molto vivace 2'27 MITROPOULOS, Dimitris (1896-1960), orchestrated by Nikos Skalkottas 16 Cretian Feast (Fête crétois) (1919, orch. 1923/24) (Manuscript) 7'20 SKALKOTTAS, Nikos (1904-1949) 17 Greek Dance in C minor (1949?) (Manuscript) 5'07 TT: 72'44 Iceland Symphony Orchestra Gu-dn´y Gu-dmundsdóttir leader Byron Fidetzis conductor 2 Nikos Skalkottas and the Greek Traditions It has become conventional to make reference to the decisive point in Skalkottas's life marked by his final return to Greece in 1933. -

2017–2018 SEASON Markand Thakar Music Director President’S Welcome!

ravo! 2017–2018 SEASON markand thakar music director president’s welcome! Welcome to Baltimore Chamber Orchestra’s 2017–2018 season: BCO’s 35th year. We are delighted to bring you five concerts again this season! Welcome to Baltimore Chamber Orchestra’s 2017–2018 season: BCO’s 35th year! We are delighted to bring you once again five outstanding concerts this season! BCO is one of the musical treasures of Baltimore. We provide compelling performances of outstanding music in a comfortable, beautiful setting that's easily accessible. Our specialty is music for smaller orchestral ensembles from the extensive classical canon. BCO provides fresh and inspiring interpretations of familiar classics, as well as an opportunity to hear less well-known masterpieces ignored by larger orchestras. BCO is Baltimore’s Intimate Classical Orchestra, striving to create musical intensity at every performance. Our Sunday afternoon audiences are passionate about our concerts and our strong reviews reflect the artistry of the orchestra. Thank you for your generous financial contributions that enable BCO to present outstanding classical music each season. Ticket revenues provide only a portion of the orchestra's operating budget. Your donations also sustain BCO’s commitment to music education of young people, including All Students Free All the Time at concerts. Live Wire String Quartet, BCO’s educational- outreach ensemble, touched the lives of more than 2,000 students last season. And, this season brings the inauguration of The Listening Lab, BCO’s second music-education project for older, elementary-school students. We are helping to create the next generation of classical music lovers! I would also like to highlight our Music Director Markand Thakar's exciting conducting programs each winter and summer.