JAVS 29.1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Analysis of the Six Duets for Violin and Viola by Michael Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIX DUETS FOR VIOLIN AND VIOLA BY MICHAEL HAYDN AND WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART by Euna Na Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2021 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Frank Samarotto, Research Director ______________________________________ Mark Kaplan, Chair ______________________________________ Emilio Colón ______________________________________ Kevork Mardirossian April 30, 2021 ii I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of my mentor Professor Ik-Hwan Bae, a devoted musician and educator. iii Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ iv List of Examples .............................................................................................................................. v List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. vii Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Unaccompanied Instrumental Duet... ................................................................... 3 A General Overview -

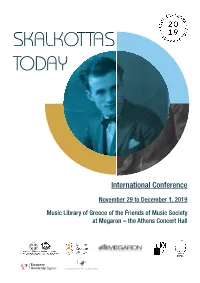

SKALKOTTAS Program 148X21

International Conference Program NOVEMBER 29 TO DECEMBER 1, 2019 Music Library of Greece of the Friends of Music Society at Megaron – the Athens Concert Hall Organised by the Music Library of Greece “Lilian Voudouri” of the Friends of Music Society, Megaron—The Athens Concert Hall, Athens State Orchestra, Greek Composer’s Union, Foundation of Emilios Chourmouzios—Marika Papaioannou, and European University of Cyprus. With the support of the Ministry of Culture and Sports, General Directorate of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage, Directorate of Modern Cultural Heritage The conference is held under the auspices of the International Musicological Society (IMS) and the Hellenic Musicological Society It is with great pleasure and anticipa- compositional technique. This confer- tion that this conference is taking place ence will give a chance to musicolo- Organizing Committee: Foreword .................................... 3 in the context of “2019 - Skalkottas gists and musicians to present their Thanassis Apostolopoulos Year”. The conference is dedicated to research on Skalkottas and his environ- the life and works of Nikos Skalkottas ment. It is also happening Today, one Alexandros Charkiolakis Schedule .................................... 4 (1904-1949), one of the most important year after the Aimilios Chourmouzios- Titos Gouvelis Greek composers of the twentieth cen- Marika Papaioannou Foundation depos- tury, on the occasion of the 70th anni- ited the composer’s archive at the Music Petros Fragistas Abstracts .................................... 9 versary of his death and the deposition Library of Greece “Lilian Voudouri” of Vera Kriezi of his Archive at the Music Library of The Friends of Music Society to keep Greece “Lilian Voudouri” of The Friends safe, document and make it available for Martin Krithara Biographies ............................. -

Laura Marling - Song for Our Daughter Episode 184

Song Exploder Laura Marling - Song For Our Daughter Episode 184 Hrishikesh: You’re listening to Song Exploder, where musicians take apart their songs and piece by piece tell the story of how they were made. My name is Hrishikesh Hirway. (“Song for Our Daughter” by LAURA MARLING) Hrishikesh: Before we start, I want to mention that, in this episode, there’s some discussions of themes that might be difficult for some: sexual harassment and assault, as well as a mention of rape and suicide. Please use your best discretion. Laura Marling is a singer and songwriter from London. She won the Brit Award for Best British Female Solo Artist - she’s been nominated five times for that, along with the Mercury Prize, and the Grammy for Best Folk Album. Since 2008, she’s released seven albums. The most recent is called Song for Our Daughter. It’s also the name of the song that she takes apart in this episode. I spoke to Laura while she was in her home studio in London. (“Song for Our Daughter” by LAURA MARLING) Laura: My name is Laura Marling. (Music fades out) Laura: This is the longest I've ever taken to write a record. You know, I started very young. I put out my first album when I was 17, and I'm now 30. When I was young, in a really wonderful way, and I think everybody experiences this when they're young, you're kind of a functioning narcissist [laughter], in that you have this experience of the world, in which you are the central character. -

Twelve-Tone Technique and Modality in Nikos Skalkottas's Music

IMS-RASMB, Series Musicologica Balcanica 1.1, 2020. e-ISSN: 2654-248X Twelve-tone Technique and Modality in Nikos Skalkottas’s Music by George Zervos DOI: https://doi.org/10.26262/smb.v1i1.7754 ©2020 The Author. This is an open access article under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCom- mercial NoDerivatives International 4.0 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the articles is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made. Zervos, Twelve-Tone Technique and Modality… Twelve-Tone Technique and Modality in Nikos Skalkottas’s Music George Zervos Abstract In Nikos Skalkottas’s compositional output, the use of modality through the folk tra- dition, is not limited to some of the tonal works, such as the 36 Greek Dances, but it also extends to the strictly or freely twelve-tone works; indeed, this is the case throughout the composer’s creative life. Given the changing character of the ways in which this folk tradition is incorporated into a twelve-tone and, in general, an atonal environ- ment, we chose two works from different periods, in order to show the modes in which the composer manages to connect the various aspects of the twelve-tone with modal- ity: these are the first movement of Sonatina No.2 for violin and piano (1929), and the first movement of Petite Suite No.1 for solo violin and piano (1946). More specifically, in the first case, we will show the ways in which the prime row is transformed into a diatonic- chromatic-like modality, and in the second case we will discuss the function of the combination of two complementary hexachords through which two sets are produced. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Classical Music Manuscripts Collection Finding Aid (PDF)

University of Missouri-Kansas City Dr. Kenneth J. LaBudde Department of Special Collections NOT TO BE USED FOR PUBLICATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Biographical Sketches …………………………………………………………………... 2 Scope and Content …………………………………………………………………………... 13 Series Notes …………………………………………………………………………………... 13 Container List …………………………………………………………………………………... 15 Robert Ambrose …………………………………………………………………... 15 Florence Aylward …………………………………………………………………... 15 J.W.B. …………………………………………………………………………………... 15 Jean-Guillain Cardon …………………………………………………………………... 15 Evaristo Felice Dall’Abaco …………………………………………………………... 15 Alphons Darr …………………………………………………………………………... 15 P.F. Fierlein …………………………………………………………………………... 15 Franz Jakob Freystadtler …………………………………………………………... 16 Georg Golterman …………………………………………………………………... 16 Gottlieb Graupner …………………………………………………………………... 16 W. Moralt …………………………………………………………………………... 16 Pietro Nardini …………………………………………………………………………... 17 Camillo de Nardis …………………………………………………………………... 17 Alessandro Rolla …………………………………………………………………... 17 Paul Alfred Rubens …………………………………………………………………... 17 Camillo Ruspoli di Candriano …………………………………………………... 17 Domenico Scarlatti …………………………………………………………………... 17 Friederich Schneider …………………………………………………………………... 17 Ignaz Umlauf …………………………………………………………………………... 17 Miscellaneous Collections …………………………………………………………... 17 Unknown …………………………………………………………………………... 18 MS226-Classical Music Manuscripts Collection 1 University of Missouri-Kansas City Dr. Kenneth J. LaBudde Department of Special Collections NOT TO BE USED FOR PUBLICATION -

Gardiner's Schumann

Sunday 11 March 2018 7–9pm Barbican Hall LSO SEASON CONCERT GARDINER’S SCHUMANN Schumann Overture: Genoveva Berlioz Les nuits d’été Interval Schumann Symphony No 2 SCHUMANN Sir John Eliot Gardiner conductor Ann Hallenberg mezzo-soprano Recommended by Classic FM Streamed live on YouTube and medici.tv Welcome LSO News On Our Blog This evening we hear Schumann’s works THANK YOU TO THE LSO GUARDIANS WATCH: alongside a set of orchestral songs by another WHY IS THE ORCHESTRA STANDING? quintessentially Romantic composer – Berlioz. Tonight we welcome the LSO Guardians, and It is a great pleasure to welcome soloist extend our sincere thanks to them for their This evening’s performance of Schumann’s Ann Hallenberg, who makes her debut with commitment to the Orchestra. LSO Guardians Second Symphony will be performed with the Orchestra this evening in Les nuits d’été. are those who have pledged to remember the members of the Orchestra standing up. LSO in their Will. In making this meaningful Watch as Sir John Eliot Gardiner explains I would like to take this opportunity to commitment, they are helping to secure why this is the case. thank our media partners, medici.tv, who the future of the Orchestra, ensuring that are broadcasting tonight’s concert live, our world-class artistic programme and youtube.com/lso and to Classic FM, who have recommended pioneering education and community A warm welcome to this evening’s LSO tonight’s concert to their listeners. The projects will thrive for years to come. concert at the Barbican, as we are joined by performance will also be streamed live on WELCOME TO TONIGHT’S GROUPS one of the Orchestra’s regular collaborators, the LSO’s YouTube channel, where it will lso.co.uk/legacies Sir John Eliot Gardiner. -

Photo Needed How Little You

HOW LITTLE YOU ARE For Voices And Guitars BY NICO MUHLY WORLD PREMIERE PHOTO NEEDED Featuring ALLEGRO ENSEMBLE, CONSPIRARE YOUTH CHOIRS Nina Revering, conductor AUSTIN CLASSICAL GUITAR YOUTH ORCHESTRA Brent Baldwin, conductor HOW LITTLE YOU ARE BY NICO MUHLY | WORLD PREMIERE TEXAS PERFORMING ARTS PROGRAM: PLEASESEEINSERTFORTHEFIRSTHALFOFTHISEVENING'SPROGRAM ABOUT THE PROGRAM Sing Gary Barlow & Andrew Lloyd Webber, arr. Ed Lojeski From the first meetings aboutHow Little Renowned choral composer Eric Whitacre You Are, the partnering organizations was asked by Disney executives in 2009 Powerman Graham Reynolds knew we wanted to involve Conspirare to compose for a proposed animated film Youth Choirs and Austin Classical Guitar based on Rudyard Kipling’s beautiful story Libertango Ástor Piazzolla, arr. Oscar Escalada Youth Orchestra in the production and are The Seal Lullaby. Whitacre submitted this Austin Haller, piano delighted that they are performing these beautiful, lyrical work to the studios, but was works. later told that they decided to make “Kung The Seal Lullaby Eric Whitacre Fu Panda” instead. With its universal message issuing a quiet Shenandoah Traditional, arr. Matthew Lyons invitation, Gary Barlow and Andrew Lloyd In honor of the 19th-century American Webber’s Sing, commissioned for Queen poetry inspiring Nico Muhly’s How Little That Lonesome Road James Taylor & Don Grolnick, arr. Matthew Lyons Elizabeth’s Diamond Jubilee in 2012, brings You Are, we chose to end the first half with the sweetness of children’s voices to brilliant two quintessentially American folk songs Featuring relief. arranged for this occasion by Austin native ALLEGRO ENSEMBLE, CONSPIRARE YOUTH CHOIRS Matthew Lyons. The haunting and beautiful Nina Revering, conductor Powerman by iconic Austin composer Shenandoah precedes James Taylor’s That Graham Reynolds was commissioned Lonesome Road, setting the stage for our AUSTIN CLASSICAL GUITAR YOUTH ORCHESTRA by ACG for the YouthFest component of experience of Muhly’s newest masterwork. -

Highly Anticipated Non-Profit Music Venue in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, Announces Opening, Curators, Programming Details and a New Name

For Immediate Release May 8, 2015 Press Contacts: Blake Zidell, John Wyszniewski and Ron Gaskill at Blake Zidell & Associates: 718.643.9052, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. HIGHLY ANTICIPATED NON-PROFIT MUSIC VENUE IN WILLIAMSBURG, BROOKLYN, ANNOUNCES OPENING, CURATORS, PROGRAMMING DETAILS AND A NEW NAME Beginning in October, National Sawdust (Formerly Original Music Workshop) Will Provide Composers and Musicians a State-of-the-Art Home for the Creation of New Work and Will Give Audiences and a Place to Discover Genre-Spanning Music at Accessible Ticket Prices Curators to Include Composers Anna Clyne, Bryce Dessner, David T. Little and Nico Muhly; Pianists Simone Dinnerstein and Anne Marie McDermott; Vocalists Helga Davis, Theo Bleckmann and Magos Herrera; and Violinists Miranda Cuckson and Tim Fain Groups and Artists in Residence to Include Brooklyn Rider, Glenn Kotche (Wilco), Alicia Hall Moran and Zimbabwe’s Netsayi Venue Partners and Collaborators Range from Carnegie Hall's Weill Music Institute and the New York Philharmonic’s CONTACT! to Stanford University and Williamsburg-Based El Puente Center for Arts and Culture National Sawdust +, Created by Elena Park, Will Include National Sawdust Talks as well as Performance Series that Offer Leading Directors and Writers, from Richard Eyre to Michael Mayer, a Platform to Share Their Musical Passions Opening Concerts in October to Feature Terry Riley, John Zorn, Roomful of Teeth, Nico Muhly, Bryce Dessner, Fence Bower Jon Rose, Throat Singer Tanya Tagaq and Others Brooklyn, NY (May 7, 2015) - The non-profit National Sawdust, formerly known as Original Music Workshop, is pleased to announce that its highly anticipated, state-of-the-art, Williamsburg, Brooklyn venue will open this fall. -

Concerts from the Library of Congress 2012-2013

Concerts from the Library of Congress 2012-2013 LIBRARY LATE ACME & yMusic Friday, November 30, 2012 9:30 in the evening sprenger theater Atlas performing arts center The McKim Fund in the Library of Congress was created in 1970 through a bequest of Mrs. W. Duncan McKim, concert violinist, who won international prominence under her maiden name, Leonora Jackson; the fund supports the commissioning and performance of chamber music for violin and piano. Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. Please take note: UNAUTHORIZED USE OF PHOTOGRAPHIC AND SOUND RECORDING EQUIPMENT IS STRICTLY PROHIBITED. PATRONS ARE REQUESTED TO TURN OFF THEIR CELLULAR PHONES, ALARM WATCHES, OR OTHER NOISE-MAKING DEVICES THAT WOULD DISRUPT THE PERFORMANCE. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. Please recycle your programs at the conclusion of the concert. THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Atlas Performing Arts Center FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2012, at 9:30 p.m. THE mckim Fund In the Library of Congress American Contemporary Music Ensemble Rob Moose and Caleb Burhans, violin Nadia Sirota, viola Clarice Jensen, cello Timothy Andres, piano CAROLINE ADELAIDE SHAW Limestone and Felt, for viola and cello DON BYRON Spin, for violin and piano (McKim Fund Commission) JOHN CAGE (1912-1992) String Quartet in Four Parts (1950) Quietly Flowing Along Slowly Rocking Nearly Stationary Quodlibet MICK BARR ACMED, for violin, viola and cello Intermission *Meet the Artists* yMusic Alex Sopp, flutes Hideaki Aomori, clarinets C.J. -

Herminie a Performer's Guide to Hector Berlioz's Prix De Rome Cantata Rosella Lucille Ewing Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2009 Herminie a performer's guide to Hector Berlioz's Prix de Rome cantata Rosella Lucille Ewing Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ewing, Rosella Lucille, "Herminie a performer's guide to Hector Berlioz's Prix de Rome cantata" (2009). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2043. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2043 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. HERMINIE A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO HECTOR BERLIOZ’S PRIX DE ROME CANTATA A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music and Dramatic Arts by Rosella Ewing B.A. The University of the South, 1997 M.M. Westminster Choir College of Rider University, 1999 December 2009 DEDICATION I wish to dedicate this document and my Lecture-Recital to my parents, Ward and Jenny. Without their unfailing love, support, and nagging, this degree and my career would never have been possible. I also wish to dedicate this document to my beloved teacher, Patricia O’Neill. You are my mentor, my guide, my Yoda; you are the voice in my head helping me be a better teacher and singer. -

March 23, 2012 Masters of Tradition Celebrates the Art of Irish Music At

March 23, 2012 Masters of Tradition celebrates the art of Irish music at the Annenberg Center “A terrifically enjoyable show—accomplished line-up...thrilling climax of galloping jigs and reels.” The Australian (Philadelphia, March 23, 2012)—In its American debut, Masters of Tradition, the ensemble comprised of seven of Ireland's most compelling musicians, brings the heart of Ireland to the Annenberg Center stage. Named for the music festival held each August in the Irish coastal town of Bantry, West County Cork and curated by renowned fiddler Martin Hayes, Masters of Tradition captivates audiences with intimate performances and dazzling instrumentals. The performance will take place on April 15, 2012 at 7 PM. Tickets are $20-$40 (prices are subject to change). For tickets or for more information, please visit AnnenbergCenter.org or call 215.898.3900. Tickets can also be purchased in person at the Annenberg Center Box Office. A celebration of traditional Irish music in its purest form, the performance will showcase a variety of intimate solos, duets and trios as well as full group collaborations. The ensemble reads as a ‘who’s who’ in Irish music and includes vocalist Iarla Ó Lionnáird, fiddlers Martin Hayes and Cathal Hayden, guitarists Dennis Cahill and Seamie O’Dowd, accordionist Máirtín O’Connor and piper David Power. Artistic director Martin Hayes launched the Masters of Tradition Festival in 2002. "The goal of this tour is to focus on the nuances of Irish traditional music," says Hayes. "The performers are all masters of their instruments. Through their talent and abilities, the sophistication and artfulness of the music is revealed." Born in East County Clare, a part of Ireland renowned for traditional music, Hayes is lauded for his distinctly lyrical style.