Lightspeed Magazine, Issue 121 (June 2020)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deadlands: Reloaded Core Rulebook

This electronic book is copyright Pinnacle Entertainment Group. Redistribution by print or by file is strictly prohibited. This pdf may be printed for personal use. The Weird West Reloaded Shane Lacy Hensley and BD Flory Savage Worlds by Shane Lacy Hensley Credits & Acknowledgements Additional Material: Simon Lucas, Paul “Wiggy” Wade-Williams, Dave Blewer, Piotr Korys Editing: Simon Lucas, Dave Blewer, Piotr Korys, Jens Rushing Cover, Layout, and Graphic Design: Aaron Acevedo, Travis Anderson, Thomas Denmark Typesetting: Simon Lucas Cartography: John Worsley Special Thanks: To Clint Black, Dave Blewer, Kirsty Crabb, Rob “Tex” Elliott, Sean Fish, John Goff, John & Christy Hopler, Aaron Isaac, Jay, Amy, and Hayden Kyle, Piotr Korys, Rob Lusk, Randy Mosiondz, Cindi Rice, Dirk Ringersma, John Frank Rosenblum, Dave Ross, Jens Rushing, Zeke Sparkes, Teller, Paul “Wiggy” Wade-Williams, Frank Uchmanowicz, and all those who helped us make the original Deadlands a premiere property. Fan Dedication: To Nick Zachariasen, Eric Avedissian, Sean Fish, and all the other Deadlands fans who have kept us honest for the last 10 years. Personal Dedication: To mom, dad, Michelle, Caden, and Ronan. Thank you for all the love and support. You are my world. B.D.’s Dedication: To my parents, for everything. Sorry this took so long. Interior Artwork: Aaron Acevedo, Travis Anderson, Chris Appel, Tom Baxa, Melissa A. Benson, Theodor Black, Peter Bradley, Brom, Heather Burton, Paul Carrick, Jim Crabtree, Thomas Denmark, Cris Dornaus, Jason Engle, Edward Fetterman, -

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

The Dominican Charism in American Higher Education:A

The Dominican Charism in American Higher Education: VisionA Servicein ofTruth Inspired by the 12th Biennial Colloquium of Dominican Colleges and Universities 1 Now to each one the manifestation of the Spirit is given This document was commissioned by the presidents of the Dominican for the common good. To one there is given through the Spirit colleges and universities in the U.S. in conjunction with the 2012 a message of wisdom, to another a message of knowledge by Dominican Higher Education Colloquium entitled The Contemplative Vision: Love, Truth and Reality. It is intended to be “a conversation means of the same Spirit, to another faith by the same Spirit, starter” within and among the institutions of Dominican higher education to another gifts of healing by that one Spirit, to another miraculous in the United States to stimulate research and writing that will further powers, to another prophecy, to another distinguishing between explore and articulate the richness of the Dominican tradition. All are spirits, to another speaking in different kinds of tongues, and to invited to bring their scholarship, convictions and experiences to the conversation. still another the interpretation of tongues. All these are the work of one and the same Spirit, and he distributes them to each Thanks to the initiative of President Donna M. Carroll, Dominican one, just as he determines. 1 Cor 12: 7-11 University has assumed responsibility for the publication of the document and will serve as the distribution center for copies requested by Dominican institutions. Introduction Special thanks go to the American Dominicans who formed the The future of American Dominican institutions of higher education is, in writing team: large part, in the hands of dedicated lay women and men. -

A Matter of Truth

A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle for African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) Cover images: African Mariner, oil on canvass. courtesy of Christian McBurney Collection. American Indian (Ninigret), portrait, oil on canvas by Charles Osgood, 1837-1838, courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society Title page images: Thomas Howland by John Blanchard. 1895, courtesy of Rhode Island Historical Society Christiana Carteaux Bannister, painted by her husband, Edward Mitchell Bannister. From the Rhode Island School of Design collection. © 2021 Rhode Island Black Heritage Society & 1696 Heritage Group Designed by 1696 Heritage Group For information about Rhode Island Black Heritage Society, please write to: Rhode Island Black Heritage Society PO Box 4238, Middletown, RI 02842 RIBlackHeritage.org Printed in the United States of America. A MATTER OF TRUTH The Struggle For African Heritage & Indigenous People Equal Rights in Providence, Rhode Island (1620-2020) The examination and documentation of the role of the City of Providence and State of Rhode Island in supporting a “Separate and Unequal” existence for African heritage, Indigenous, and people of color. This work was developed with the Mayor’s African American Ambassador Group, which meets weekly and serves as a direct line of communication between the community and the Administration. What originally began with faith leaders as a means to ensure equitable access to COVID-19-related care and resources has since expanded, establishing subcommittees focused on recommending strategies to increase equity citywide. By the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society and 1696 Heritage Group Research and writing - Keith W. Stokes and Theresa Guzmán Stokes Editor - W. -

Hugo Awards Issue H

HUGO ISSUE The Solitary Star SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 1, 2013 2013 Hugo Awards Best Novel: Redshirts: A Novel with Three Codas by John Scalzi (Tor) Best Novella: “The Emperor's Soul” by Brandon Sanderson (Tachyon Publications) Best Novelette: “The Girl-Thing Who Went Out for Sushi” by Pat Cadigan (Edge of Infinity, Solaris) Best Short Story: “Mono no aware” by Ken Liu (The Future is Japanese, VIZ Media LLC) Best Related Work: Writing Excuses, Season 7 by Brandon Sanderson, Dan Wells, Mary Robinette Kowal, Howard Tayler, and Jordan Sanderson Best Graphic Story: Saga, Volume 1 written by Brian K. Vaughan, illustrated by Fiona Staples (Image Comics) Best Dramatic Presentation (Long Form): The Avengers Screenplay & Directed by Joss Whedon (Marvel Studios, Disney, Paramount) Best Dramatic Presentation (Short Form): Game of Thrones: “Blackwater” Written by George R.R. Martin, Directed by Neil Marshall. Created by David Benioff and D.B. Weiss (HBO) Best Editor – Short Form: Stanley Schmidt Best Editor – Long Form: Patrick Nielsen Hayden Best Professional Artist: John Picacio Best Semiprozine: Clarkesworld edited by Neil Clarke, Jason Heller, Sean Wallace and Kate Baker Best Fanzine: SF Signal edited by John DeNardo, JP Frantz, and Patrick Hester Best Fancast: SF Squeecast, Elizabeth Bear, Paul Cornell, Seanan McGuire, Lynne M. Thomas, Catherynne M. Valente (Presenters) and David McHone-Chase (Technical Producer) Best Fan Writer: Tansy Rayner Roberts Best Fan Artist: Galen Dara John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer: Mur Lafferty Total number of valid ballots received: 1,848 Number of ballots needed to pass the 25% rule: 462 All categories passed easily Hugo Administration: Todd Dashoff Hugo Awards Subcommittee: Todd Dashoff, Vincent Docherty, Saul Jaffe, Steven Staton, Beth Welsh, Ben Yalow Hugo Final Ballot Counting Software: Jeff Copeland Hugo Packet: Beth Welsh o Hugo Packet Staff: Andrew A. -

Nightmare Magazine, Issue 43 (April 2016)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 43, April 2016 FROM THE EDITOR Editorial, April 2016 FICTION Reaper’s Rose Ian Whates Death’s Door Café Kaaron Warren The Girl Who Escaped From Hell Rahul Kanakia The Grave P.D. Cacek NONFICTION The H Word: The Monstrous Intimacy of Poetry in Horror Evan J. Peterson Artist Showcase: Yana Moskaluk Marina J. Lostetter Interview: David J. Schow Lisa Morton AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS Ian Whates Kaaron Warren Rahul Kanakia P.D. Cacek MISCELLANY Coming Attractions Stay Connected Subscriptions and Ebooks About the Nightmare Team Also Edited by John Joseph Adams © 2016 Nightmare Magazine Cover by Yana Moskaluk www.nightmare-magazine.com FROM THE EDITOR Editorial, April 2016 John Joseph Adams | 750 words Welcome to issue forty-three of Nightmare! This month, we have original fiction from Ian Whates (“Reaper’s Rose”) and Rahul Kanakia (“The Girl Who Escaped From Hell”), along with reprints by Kaaron Warren (“Death’s Door Cafe”) and P.D. Cacek (“The Grave”). We also have the latest installment of our column on horror, “The H Word,” plus author spotlights with our authors, a showcase on our cover artist, and a feature interview with author David J. Schow. Nebula Award Nominations ICYMI last month, awards season is officially upon us, and it looks like 2015 was a terrific year for our publications. The first of the major awards have announced their lists of finalists for last year’s work, and we’re pleased to announce that “Hungry Daughters of Starving Mothers” by Alyssa Wong (Nightmare, Oct. 2015) is a finalist for the Nebula Award this year! Over at Lightspeed, “Madeleine” by Amal El-Mohtar (Lightspeed, June 2015) and “And You Shall Know Her by the Trail of Dead” by Brooke Bolander (Lightspeed, Feb. -

Regimes of Truth in the X-Files

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 1-1-1999 Aliens, bodies and conspiracies: Regimes of truth in The X-files Leanne McRae Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation McRae, L. (1999). Aliens, bodies and conspiracies: Regimes of truth in The X-files. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ theses/1247 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1247 Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 1999 Aliens, bodies and conspiracies : regimes of truth in The -fiX les Leanne McRae Edith Cowan University Recommended Citation McRae, L. (1999). Aliens, bodies and conspiracies : regimes of truth in The X-files. Retrieved from http://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1247 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. http://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1247 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). -

Strangest of All

Strangest of All 1 Strangest of All TRANGEST OF LL AnthologyS of astrobiological science A fiction ed. Julie Nov!"o ! Euro#ean Astrobiology $nstitute Features G. %avid Nordley& Geoffrey Landis& Gregory 'enford& Tobias S. 'uc"ell& (eter Watts and %. A. *iaolin S#ires. + Strangest of All , Strangest of All Edited originally for the #ur#oses of 'EACON +.+.& a/conference of the Euro#ean Astrobiology $nstitute 0EA$1. -o#yright 0-- 'Y-N--N% 4..1 +.+. Julie No !"o ! 2ou are free to share this 5or" as a 5hole as long as you gi e the ap#ro#riate credit to its creators. 6o5ever& you are #rohibited fro7 using it for co77ercial #ur#oses or sharing any 7odified or deri ed ersions of it. 8ore about this #articular license at creati eco77ons.org9licenses9by3nc3nd94.0/legalcode. While this 5or" as a 5hole is under the -reati eCo77ons Attribution3 NonCo77ercial3No%eri ati es 4.0 $nternational license, note that all authors retain usual co#yright for the indi idual wor"s. :$ntroduction; < +.+. by Julie No !"o ! :)ar& $ce& Egg& =ni erse; < +..+ by G. %a id Nordley :$nto The 'lue Abyss; < 1>>> by Geoffrey A. Landis :'ac"scatter; < +.1, by Gregory 'enford :A Jar of Good5ill; < +.1. by Tobias S. 'uc"ell :The $sland; < +..> by (eter )atts :SET$ for (rofit; < +..? by Gregory 'enford :'ut& Still& $ S7ile; < +.1> by %. A. Xiaolin S#ires :After5ord; < +.+. by Julie No !"o ! :8artian Fe er; < +.1> by Julie No !"o ! 4 Strangest of All :@this strangest of all things that ever ca7e to earth fro7 outer space 7ust ha e fallen 5hile $ 5as sitting there, isible to 7e had $ only loo"ed u# as it #assed.; A H. -

Spring 2021 Tor Catalog (PDF)

21S Macm TOR Page 1 of 41 The Blacktongue Thief by Christopher Buehlman Set in a world of goblin wars, stag-sized battle ravens, and assassins who kill with deadly tattoos, Christopher Buehlman's The Blacktongue Thief begins a 'dazzling' (Robin Hobb) fantasy adventure unlike any other. Kinch Na Shannack owes the Takers Guild a small fortune for his education as a thief, which includes (but is not limited to) lock-picking, knife-fighting, wall-scaling, fall-breaking, lie-weaving, trap-making, plus a few small magics. His debt has driven him to lie in wait by the old forest road, planning to rob the next traveler that crosses his path. But today, Kinch Na Shannack has picked the wrong mark. Galva is a knight, a survivor of the brutal goblin wars, and handmaiden of the goddess of death. She is searching for her queen, missing since a distant northern city fell to giants. Tor On Sale: May 25/21 Unsuccessful in his robbery and lucky to escape with his life, Kinch now finds 5.38 x 8.25 • 416 pages his fate entangled with Galva's. Common enemies and uncommon dangers 9781250621191 • $34.99 • CL - With dust jacket force thief and knight on an epic journey where goblins hunger for human Fiction / Fantasy / Epic flesh, krakens hunt in dark waters, and honor is a luxury few can afford. Notes The Blacktongue Thief is fast and fun and filled with crazy magic. I can't wait to see what Christopher Buehlman does next." - Brent Weeks, New York Times bestselling author of the Lightbringer series Promotion " National print and online publicity campaign Dazzling. -

No. 3 / May 2014 Ecdysis Masthead

No. 3 / May 2014 Ecdysis Masthead Ecdysis No. 3 / May 2014 Jonathan Crowe editor Zvi Gilbert Jennifer Seely art Tamara Vardomskaya Send hate mail, letters of comment, and submissions to: All content is copyright © their respective contributors. mail PO Box 473 Shawville QC J0X 2Y0 Photo/illustration credits: [1, 8, 17, 19, 24] Art by CANADA Jennifer Seely. [25] Photo of Samuel R. Delany by e-mail [email protected] Houari B., and used under the terms of its Creative web mcwetboy.net/ecdysis Commons Licence. 2 Some Twitter responses to a mass e-mail begging fellow SFWA members for a Nebula nomination in early January 2014. EDITORIAL The Value of Awards I’ll be honest: I have ambivalent feelings ess, or whether the wrong works or individu- about awards. als were nominated, or whether the wrong On the one hand, I find awards useful: works or individuals won, as so many fans when so much is published in science fiction seem to do every year. and fantasy every year, they serve to winnow No, the problem I have with awards is the wheat from the chaff. For the past few how much we talk about them, and how im- years I’ve made a point of reading as many of portant we make them. the award nominees as possible, even if I’m Which is to say: too much and too much. not in a position to vote for them. One problem with awards is that there But on the other hand, I find awards an- are so many of them. -

View Program Book

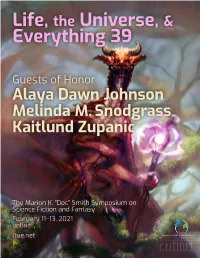

Life, the Universe, & Everything 39 Guests of Honor Alaya Dawn Johnson Melinda M. Snodgrass Kaitlund Zupanic The Marion K. “Doc” Smith Symposium on Science Fiction and Fantasy February 11–13, 2021 online Watcher in the Mist © Kaitlund Zupanic; ltue.net used by permission Letter from the Chair Oh what a year it has been since we last came together! rewarding to see the committee moving forward even as Neither of us ever thought we would start 2020 by throw- we, their Co-Chairs, were struggling with trials that kept ing our hats in as Co-Chairs for the volunteer commit- us from leading in the way we wanted to. tee. And we, like the rest of the world, never expected Whether we are meeting much too close together in the series of events that would become known simply as cramped hotel event rooms or much too far apart in vir- “2020” and that would continue into 2021. tual video channels, LTUE continues to be a place where It has been incredible seeing how everyone has come creators and fans of speculative fiction can come together together to support each other in turbulent times. Our to take a break from the world and support, teach, and committee had to evolve quickly to adapt to the pandemic, inspire one another in an event that is truly unlike any shifting to virtual meetings and eventually moving our other. We look forward to seeing you all in person next entire event online. It’s been inspiring to watch com- year. mittee members step up to help as others were dealing So long and thanks for all the fish! with personal challenges. -

July 2019 Table of Contents

July 2019 Table of Contents A Not-So-Final Note from the Editor ........................................................................................................... 1 From the Trenches ......................................................................................................................................... 3 HWA Mentor Program Update ..................................................................................................................... 4 The Seers Table! ............................................................................................................................................ 5 HWA Events – Current for 2019 ................................................................................................................. 10 Utah Chapter Update .................................................................................................................................. 11 Pennsylvania Chapter Update ................................................................................................................... 13 San Diego Chapter Update ......................................................................................................................... 16 Wisconsin Chapter Update ......................................................................................................................... 17 LA Chapter Update ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Ohio Chapter Update