Working Together When Facing Chronic Pain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

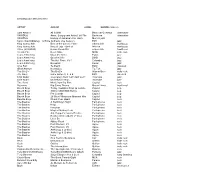

Song Name Artist

Sheet1 Song Name Artist Somethin' Hot The Afghan Whigs Crazy The Afghan Whigs Uptown Again The Afghan Whigs Sweet Son Of A Bitch The Afghan Whigs 66 The Afghan Whigs Cito Soleil The Afghan Whigs John The Baptist The Afghan Whigs The Slide Song The Afghan Whigs Neglekted The Afghan Whigs Omerta The Afghan Whigs The Vampire Lanois The Afghan Whigs Saor/Free/News from Nowhere Afro Celt Sound System Whirl-Y-Reel 1 Afro Celt Sound System Inion/Daughter Afro Celt Sound System Sure-As-Not/Sure-As-Knot Afro Celt Sound System Nu Cead Againn Dul Abhaile/We Cannot Go... Afro Celt Sound System Dark Moon, High Tide Afro Celt Sound System Whirl-Y-Reel 2 Afro Celt Sound System House Of The Ancestors Afro Celt Sound System Eistigh Liomsa Sealad/Listen To Me/Saor Reprise Afro Celt Sound System Amor Verdadero Afro-Cuban All Stars Alto Songo Afro-Cuban All Stars Habana del Este Afro-Cuban All Stars A Toda Cuba le Gusta Afro-Cuban All Stars Fiesta de la Rumba Afro-Cuban All Stars Los Sitio' Asere Afro-Cuban All Stars Pío Mentiroso Afro-Cuban All Stars Maria Caracoles Afro-Cuban All Stars Clasiqueando con Rubén Afro-Cuban All Stars Elube Chango Afro-Cuban All Stars Two of Us Aimee Mann & Michael Penn Tired of Being Alone Al Green Call Me (Come Back Home) Al Green I'm Still in Love With You Al Green Here I Am (Come and Take Me) Al Green Love and Happiness Al Green Let's Stay Together Al Green I Can't Get Next to You Al Green You Ought to Be With Me Al Green Look What You Done for Me Al Green Let's Get Married Al Green Livin' for You [*] Al Green Sha-La-La -

Arbiter, October 22 Students of Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 10-22-1997 Arbiter, October 22 Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. 'I 1 WEDNESDAt OaOBER22,1997 ---, •••• _----- -~_. __ ._--_ • .,-- •• _- --- .-._--'~'-- .. - •• ~_ - •• > WEDNESDAY, OaOBER 22, 1997 by Eric Ellis 6U'(S ::r:tJGeO@) 1b"fi.lINj(F~ A . WHIt6J So 1: nt.C(OG'O "'-0 ~AK€ A Ro,4D- TRll'S:X-rniW6St: 1 ( •••••••••••••••••••••.•••••••••••••••••.••••••• -".I!~~a.a.LIl.LL& .......-..JLLL&.LI~L&.LJ. educat.ion : I Top T~n reason's why Dirk 1 Kempthorne The { S({J)1UUrce should come for NEWS home and at become Idaho's BSU governor by Asencion Ramirez Opinion Editor 10. He's always·wanted to be the HSIC (Head Spud In Charge). 9. It's one way for the nation to stop associating him with Helen Chenoweth. (Hell,it's the reason voters sent her to Washington). 8. If he doesn't do it, Bruce Willis will. 7. "Kempthorne Kicks @$$" makes for a good slogan. 6. Spending four years in Boise seems a lot more fun than spending four more years in Washington with Larry Craig. 5. -

Cd Collection For

CD COLLECTION JAN 2013 ARTIST ALBUM LABEL GENRE (approx) Sam Amidon All Is Well Bedroom Commun. alternative VARIOUS Amer. Song-poem Anthol. 60-70s Bar/none alternative VARIOUS History of Jamaican Voc Harm. Munich jazz Cannonball Adderley & Ernie Andrews Live Session EMI jazz King Sunny Ade Best of the Classic Years Shanachie world pop King Sunny Ade King of Juju - Best of Wrasse world pop Africa (VARIOUS) Never Stand Still Ellipsis Arts traditional Arcade Fire Neon Bible MRG indie rock Louis Armstrong Mack the Knife Pablo jazz Louis Armstrong Greatest Hits BMG jazz Louis Armstrong The Hot Fives, Vol 1 Columbia jazz Louis Armstrong Essential Cedar jazz Arvo Part Te Deum ECM classical Gilad Atzmon Nostalgico Tip Toe jazz The B-52's The B-52's Warner Bros indie rock J.S. Bach Cello Suites 2, 3, & 6 EMI classical Chet Baker sings/plays from "Let's Get Lost" Riverside jazz Chet Baker Chet Baker Sings Riverside jazz The Band Music from Big Pink Capitol rock Bajourou Big String Theory Green Linnet traditional Beach Boys Today / Summer Days (& Summ.. Capitol pop Beach Boys Smiley Smile/Wild Honey Capitol pop Beach Boys Pet Sounds Capitol pop Beach Boys 20 Good Vibrations-Greatest Hits Capitol pop Beastie Boys Check Your Head Capitol rock The Beatles A Hard Day's Night Parlophone rock The Beatles Help! Parlophone rock The Beatles Revolver Parlophone rock The Beatles Magical Mystery Tour Parlophone rock The Beatles Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts… Parlophone rock The Beatles Beatles (white album) (2-disc) Parlophone rock The Beatles Let It Be Parlophone -

La Calle Ángel Gómez, La Mejor Engalanada Durante La Procesión De La Patrona

La Calle 51.qxd 24/11/06 13:20 Página 1 La Calle 51.qxd 24/11/06 13:20 Página 2 La Calle 51.qxd 24/11/06 13:20 Página 3 DICIEMBRE’06 Editorial I 3 Sumario La opinión de los lectores Al cumplir la cifra, un tanto simbólica, gar al pueblo todos los meses una La residencia de los cincuenta números, ‘La Calle’ publicación que juzgan necesaria de la tercera edad se puso en comunicación con sus lec- y oportuna para el desarrollo inte- comenzará a tores para saber qué opinan de la re- gral de nuestro pueblo. Varias per- funcionar en la vista, qué sección les gusta más, cua- sonas nos han dicho que la esperan primavera de 2008 Página 8 les son sus defectos más notables. con ansiedad, la leen de cabo a ra- Hemos publicado cuarenta opi- bo y la juzgan digna de codearse niones. Todas, sin excepción, coinci- con publicaciones que disponen de den en valorar esta publicación, re- mucho más personal y muchísimos conociendo que es un estupendo más medios. Nosotros, sinceramen- III Jornadas bien cultural para Santomera. Leer te, estamos convencidos de que, de la Asociación esas entrevistas ha sido gratificante con los medios tan modestos que Española Contra para quienes, mes tras mes, hace- tenemos, hacemos una publicación Páginas 10 a 18 el Cáncer mos ‘La Calle’ . muy decente, que se puede presen- El esfuerzo que supone escribir, tar, sin sonrojo, en cualquier sitio. buscar publicidad, realizar contactos Entre los testimonios publicados, y confeccionar la revista, se ha vis- seis confiesan que hojean la revista to gozosamente compensado por pero no la leen. -

The Neuroscience of Chronic Pain Relief

The Neuroscience of Chronic Pain Relief ✽✽✽ The Best Alternative Chronic Pain Relief Solutions author: Davoud Derogar Table of Contents Table of Contents 3 Dedication 5 Copyrights 7 Gratitude 8 Introduction 10 DISCLAIMER 12 Costs of Chronic pain and statistics 13 What is acute and chronic pain? 18 Types of pain 22 What is Pain Cycle? 26 Common Alternative Treatments for Chronic Pain: 27 Hypnosis 29 What if some chronic pain is a sign of stress? 32 The gate control theory of pain 37 How pain mechanism works 38 The Peripheral Nervous System 40 Dr. Apkar Apkarian neuroscientist 42 Who is Dr. Apkar Vania Apkarian? 44 Dr. Norman Doidge 47 Dr. Michael H Moskowitz 48 Dr. Moscowitz's story: 50 Dr. Lorimer Moseley neuroscientist 57 Who is Dr. Lorimer Moseley? 57 Dr. Lorimer Moseley's personal story 57 Dr. John Sarno surgeon 62 Psychology of psychosomatic disorder 62 TMS Theory: 64 Who was Dr. John Sarno: 66 Pete Egoscue Pain Relief Expert 69 Norman Cousins, UCLA professor 78 Helpful value, what stress does to the body! 81 Final notes about stress 89 Helpful ideas 93 About the Author 96 Knowledge quotes 98 Pain quotes 99 Final note 101 Dedication To anyone who has chronic pain. If the pain is robbing you of your quality-of-life. If pain is stopping you from enjoying time with your family and friends. If pain is stopping you from your hobbies and interests. If the pain is stopping you from being active and in control. I hope this book will give you a better understanding of chronic pain so that you can eliminate your pain, re- duce or manage your pain better and have a joyful life. -

Opioid Treatments for Chronic Pain

Comparative Effectiveness Review Disposition of Comments Report Research Review Title: Opioid Treatments for Chronic Pain Draft review available for public comment from October 15, 2019 through November 12, 2019. Research Review Citation: Chou R, Hartung D, Turner J, Blazina I, Chan B, Levander X, McDonagh M, Selph S, Fu R, Pappas M. Opioid Treatments for Chronic Pain. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 229. (Prepared by the Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2015-00009-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 20-EHC011. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; April 2020. DOI: 10.23970/AHRQEPCCER229. Posted final reports are located on the Effective Health Care Program search page. Comments to Research Review The Effective Health Care (EHC) Program encourages the public to participate in the development of its research projects. Each research review is posted to the EHC Program Web site or AHRQ Web site in draft form for public comment for a 3-4-week period. Comments can be submitted via the Web site, mail or E-mail. At the conclusion of the public comment period, authors use the commentators’ submissions and comments to revise the draft research review. Comments on draft reviews and the authors’ responses to the comments are posted for public viewing on the Web site approximately 3 months after the final research review is published. Comments are not edited for spelling, grammar, or other content errors. Each comment is listed with the name and affiliation of the commentator, if this information is provided. Commentators are not required to provide their names or affiliations in order to submit suggestions or comments. -

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 32.95 21.95 20.95 26.95 26.95

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 10" 13th Floor Elevators You`re Gonna Miss Me (pic disc) 803415820412 32.95 10" A Perfect Circle Doomed/Disillusioned 4050538363975 21.95 10" A.F.I. All Hallow's Eve (Orange Vinyl) 888072367173 20.95 10" African Head Charge 2016RSD - Super Mystic Brakes 5060263721505 26.95 10" Allah-Las Covers #1 (Ltd) 184923124217 26.95 10" Andrew Jackson Jihad Only God Can Judge Me (white vinyl) 612851017214 24.95 10" Animals 2016RSD - Animal Tracks 018771849919 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Are Back 018771893417 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Is Here (EP) 018771893516 21.95 10" Beach Boys Surfin' Safari 5099997931119 26.95 10" Belly 2018RSD - Feel 888608668293 21.95 10" Black Flag Jealous Again (EP) 018861090719 26.95 10" Black Flag Six Pack 018861092010 26.95 10" Black Lips This Sick Beat 616892522843 26.95 10" Black Moth Super Rainbow Drippers n/a 20.95 10" Blitzen Trapper 2018RSD - Kids Album! 616948913199 32.95 10" Blossoms 2017RSD - Unplugged At Festival No. 6 602557297607 31.95 (45rpm) 10" Bon Jovi Live 2 (pic disc) 602537994205 26.95 10" Bouncing Souls Complete Control Recording Sessions 603967144314 17.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Dropping Bombs On the Sun (UFO 5055869542852 26.95 Paycheck) 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Groove Is In the Heart 5055869507837 28.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Mini Album Thingy Wingy (2x10") 5055869507585 47.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre The Sun Ship 5055869507783 20.95 10" Bugg, Jake Messed Up Kids 602537784158 22.95 10" Burial Rodent 5055869558495 22.95 10" Burial Subtemple / Beachfires 5055300386793 21.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician 868798000332 22.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician (Red 868798000325 29.95 Vinyl/Indie-retail-only) 10" Cisneros, Al Ark Procession/Jericho 781484055815 22.95 10" Civil Wars Between The Bars EP 888837937276 19.95 10" Clark, Gary Jr. -

An Interview with Thomas Rickert Nathaniel A

Published in Kairos: Rhetoric, Technology, Pedagogy, 18(2), available at http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/18.2/interviews/rivers Circumnavigation: An Interview with Thomas Rickert Nathaniel A. Rivers Saint Louis University Part One: “Only the Easy Ones” Thomas Rickert: By the way... Nathaniel Rivers: What? Thomas: Why are all your pictures on Facebook now with these salmon red pants? Nathaniel: There’s just two. That’s because people like them and it keeps showing up on your feed. It’s called being a big deal. Also, they’re not salmon, they’re just red. They show up salmon. Thomas: Fair enough. Just curious. Nathaniel: So, shall we start? Thomas: Yeah, just a second. Nathaniel: Okay. No hurry. Nathaniel (Narration): While Thomas gets ready I’ll quickly tell you what we’re up to. Traveling to two breweries in St. Louis, Missouri, Thomas and I discussed his book, Ambient Rhetoric: The Attunements of Rhetorical Being, recently published by the University of Pittsburg Press as part of their Series in Composition, Literacy and Culture. This is Thomas Rickert’s second book in the series. The first was Acts of Enjoyment: Rhetoric, Žižek, and the Return of the Subject. We chose an audio interview to in some small way attune the interview itself to ambience, the sounds of bars, chatting, outbursts of yelling, peals of laughter and glasses clinking together would shape both the interview itself and its present digital form. We hope you enjoy it. Nathaniel: We are here at the 4Hands Brewery in fabulous downtown St. Louis. Thomas: We are indeed. Nathaniel: I am here with Thomas Rickert. -

Party Tunes Dj Service Artist Title 112 Dance with Me 112 It's Over Now 112 Peaches & Cream

Party Tunes Dj Service www.partytunesdjservice.com Artist Title 112 Dance With Me 112 It's Over Now 112 Peaches & Cream 112 Peaches & Cream (feat. P. Diddy) 112 U Already Know 213 Groupie Love 311 All Mixed Up 311 Amber 311 Creatures 311 It's Alright [Album Version] 311 Love Song 311 You Wouldn't Believe 702 Steelo [Album Edit] $th Ave Jones Fallin' (r)/M/A/R/R/S Pump Up the Volume (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Ame iro Rondo (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Chance Chase Classroom (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Creme Brule no Tsukurikata (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Duty of love (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Eyecatch (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Great escape (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Happy Monday (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Hey! You are lucky girl (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Kanchigai Hour (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Kaze wo Kiite (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Ki Me Ze Fi Fu (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Kitchen In The Dark (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Kotori no Etude (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Lost my pieces (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari love on the balloon (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Magic of love (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Monochrome set (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Morning Glory (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Next Mission (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Onna no Ko no Kimochi (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Psychocandy (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari READY STEADY GO! (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Small Heaven (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Sora iro no Houkago (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Startup (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Tears of dragon (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Tiger VS Dragon (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Todoka nai Tegami (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Yasashisa no Ashioto (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Yuugure no Yakusoku (ToraDora!) Horie Yui Vanilla Salt (TV-SIZE) (ToraDora!) Kugimiya Rie, Kitamura Eri & Horie Yui Pre-Parade (TV-SIZE) .38 Special Hold on Loosely 1 Giant Leap f. -

November 1995

Features BILL BRUFORD & PAT MASTELOTTO Bruford & Mastelotto's respective gigs may have headed down different musical paths in the past, but as King Crimson's navigating duo, their sights are set on the same goal—highly challenging and creative modern music. We catch up with the pair as they embark on the second leg of Crimson's international Thrak 42 tour this month. • William F. Miller JAMIE OLDAKER The Tractors are one of the newer country acts pulling in plat- inum records, but drummer Jamie Oldaker is no stranger to the big time. Heavyweights like Clapton, Stills, and Frampton have relied on his solid feel for decades. • Rick Mattingly 70 MIKE SHAPIRO "What's a nice boy like you doing in a groove like this?" He doesn't look like your typical Latin drummer—and he doesn't play like one, either. So how come Mike Shapiro is one of the most in-demand non-Brazilian "Brazilian" drummers around? • Robyn Flans 92 Volume 19, Number 11 Cover photo by Ebet Roberts Columns EDUCATION EQUIPMENT NEWS 106 ROCK'N' 10 UPDATE 22 NEW AND JAZZ CLINIC Danny Gottlieb, NOTABLE Changuito' s Groov e Jimmy DeGrasso of BY DAVID GARIBALDI Suicidal Tendencies, 26 PRODUCT AND REBECA Ian Wallace, and CLOSE-UP Tim McGraw's Billy MAULEON-SANTANA Camber 25th Mason, plus News Anniversary Series And 108 STRICTLY C6000 Cymbals TECHNIQUE 139 INDUSTRY BY RICK VAN HORN Mirror Exercises HAPPENINGS BY JOHN MARTINEZ Zildjian Day In Prague, and more 110 JAZZ DRUMMERS' DEPARTMENTS WORKSHOP Making The African- 4 EDITOR'S Swing Connection OVERVIEW BY WOODY THOMPSON 110 ARTIST ON 8 READERS' 28 Axis Pro Hi-Hat TRACK PLATFORM And Extra Hat Steve Gadd BY CHAP OSTRANDER BY MARK GRIFFITH 14 ASK A PRO 31 1995 Consumers 120 IN THE STUDIO Chad Smith and Poll Results Carlos Vega BY RICK VAN HORN The Drummer's Studio Survival Guide: Part 8, Drum 20 IT'S 34 ELECTRONIC Microphones QUESTIONABLE REVIEW BY MARK PARSONS K&K CSM 4 Snare Mic' And CTM 3 Tom Mic' 112 CRITIQUE BY MARK PARSONS 130 CONCEPTS Django Bates, Tana Reid, Starting Over and Duffy Jackson CDs, 37 D.C. -

Impeachment Process Begins for VP Gray

Impeachment IT'S THAT TIME AGAIN process begins for VP Gray Personal phone calls one accusa tion, but controversy surrounds process By PATRICK J. BERNAL NEWS EDITOR Impeachment hearings for Student Government Association Vice President Jon Gray '00 appear to be imminent as charges he made per- sonal phone calls from the SGA office arid failed -to attend a trustee meeting over January are being investigated. According to a member of the SGA Executive Board, Gray made long distance phone calls from the SGA office during November and December and did not participate in a January trustee meaning. The impeachment process began Tuesday and SGA sources reported the majority of people in SGA are aware an impeachment is underway. Gray has denied making any impeachable offenses. "I didn't make any improper phone calls. I did, however, allow for the phone to be used for what I thought were authorized phone calls," said Gray. "They may indeed not have been. I did- n't attend the emergency meeting to elect Bro Adams. I was informed about the N JENNY O'DONNELL/THE COLBY ECHO meeting two days before it happened. I J Jon Gray¦ '00 ,k" ? , "< , . - «-rr Matt King 02 makes the diff icult decision between " new " and "used" textsfor spring semester classes. Far members of the Class ' ^ don^ t drive and I had prior obligations, so of 2000, there are just over 100 days left here on Mayflower Hill, meaning their trip to the bookstore represents their last tim e , no I didn't go." through the checout line with course books in hand. -

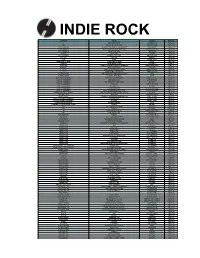

Order Form Full

INDIE ROCK ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 68 TWO PARTS VIPER COOKING VINYL RM128.00 *ASK DISCIPLINE & PRESSURE GROUND SOUND RM100.00 10, 000 MANIACS IN THE CITY OF ANGELS - 1993 BROADC PARACHUTE RM151.00 10, 000 MANIACS MUSIC FROM THE MOTION PICTURE ORIGINAL RECORD RM133.00 10, 000 MANIACS TWICE TOLD TALES CLEOPATRA RM108.00 12 RODS LOST TIME CHIGLIAK RM100.00 16 HORSEPOWER SACKCLOTH'N'ASHES MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 1975, THE THE 1975 VAGRANT RM140.00 1990S KICKS ROUGH TRADE RM100.00 30 SECONDS TO MARS 30 SECONDS TO MARS VIRGIN RM132.00 31 KNOTS TRUMP HARM (180 GR) POLYVINYL RM95.00 400 BLOWS ANGEL'S TRUMPETS & DEVIL'S TROMBONE NARNACK RECORDS RM83.00 45 GRAVE PICK YOUR POISON FRONTIER RM93.00 5, 6, 7, 8'S BOMB THE ROCKS: EARLY DAYS SWEET NOTHING RM142.00 5, 6, 7, 8'S TEENAGE MOJO WORKOUT SWEET NOTHING RM129.00 A CERTAIN RATIO THE GRAVEYARD AND THE BALLROOM MUTE RM133.00 A CERTAIN RATIO TO EACH... (RED VINYL) MUTE RM133.00 A CITY SAFE FROM SEA THROW ME THROUGH WALLS MAGIC BULLET RM74.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER BAD VIBRATIONS ADTR RECORDS RM116.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER FOR THOSE WHO HAVE HEART VICTORY RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER HOMESICK VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD VICTORY RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD (PIC) VICTORY RECORDS RM111.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER WHAT SEPARATES ME FROM YOU VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVES HAVE YOU SEEN MY PREFRONTAL CORTEX? TOPSHELF RM103.00 A LIFE ONCE LOST IRON GAG SUBURBAN HOME RM99.00 A MINOR FOREST FLEMISH ALTRUISM/ININDEPENDENCE (RS THRILL JOCKEY RM135.00 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS TRANSFIXIATION DEAD OCEANS RM102.00 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS WORSHIP DEAD OCEANS RM102.00 A SUNNY DAY IN GLASGOW SEA WHEN ABSENT LEFSE RM101.00 A WINGED VICTORY FOR THE SULLEN ATOMOS KRANKY RM128.00 A.F.I.