Comments on Removing Regulatory Barriers for Vehicles with Automated Driving Systems Docket No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Action Thriller by Alex Schuler Takes on the Controversial And

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Publication Date: 8/17/2021 Alyssia Gonzalez Trade Paper ISBN: 9781933769844 ($18.95) Book Publicist eBook ISBN: 9781933769851 ($9.99) [email protected] New Action Thriller by Alex Schuler Takes on the Controversial and Dramatic History of Self-Driving Cars Level 4 Press presents a fictionalized retelling of how the autonomous car came to be. JAMUL, CA (FEB 2020) — Author Alex Schuler captures intense determination and a clash of egos in his new action thriller, Faster. It follows a fictional engineer and computer scientist who helped pioneer the self-driving car industry while navigating their own tumultuous relationship. Their drive to take on Detroit and become leaders in this technological revolution leaves the reader in awe of what humanity can accomplish, and just how much sacrifice it takes to change the world. Autonomous car breakthroughs spiked during the DARPA challenges between 2004 and 2013, giving names to eccentric computer scientists and engineers drawn to innovation. These remarkable individuals often find themselves embroiled in controversy as they forge new paths. Robotics wonderkid Sebastian Thrun is regularly in the news for his “internet freedom” crusades. Elon Musk is legendary for breaking norms, such as the Tesla autopilot feature rushed to market in 2015. Autonomous vehicle guru Anthony Levandowski took on Google, then found himself sentenced to jail, only to be pardoned by former president Donald Trump. These pioneers dedicated their lives to technological progress. But what’s behind their drive—self-interest or a desire to improve society? Or some of both? Alex Schuler fictionalizes the autonomous car industry’s past, exploring the motivations of these innovators and asking what we can expect for the future. -

Supplementary Submission Intellectual Property And

MAY 2017 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STANDING COMMITTEE ON INDUSTRY, INNOVATION, SCIENCE AND RESOURCES SUPPLEMENTARY SUBMISSION INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND SELF-DRIVING CARS: WAYMO VS UBER DR MATTHEW RIMMER PROFESSOR OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND INNOVATION LAW FACULTY OF LAW QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Queensland University of Technology 2 George Street GPO Box 2434 Brisbane Queensland 4001 Australia Work Telephone Number: SUPPLEMENTARY SUBMISSION INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND SELF-DRIVING CARS: WAYMO VS UBER Matthew Rimmer While the Australian Parliament has been inquiring into social issues relating to land-based driverless vehicles in Australia since February 2017, intellectual property litigation has erupted in the courts between Waymo (Google’s Self-Driving Car Project) and Uber in the United States. The case has attracted much public attention. Alex Davies has reflected: Until today, the race to build a self-driving car seemed to hinge on who had the best technology. Now it’s become a case of full-blown corporate intrigue. Alphabet’s self-driving startup, Waymo, is suing Uber, accusing the ridesharing giant of stealing critical autonomous driving technology. If the suit goes to trial, Apple’s legal battle with Samsung could wind up looking tame by comparison.1 The intellectual property dispute could have significant implications for competition in respect of self-driving cars and autonomous vehicles. The New York Times has noted that ‘companies in Silicon Valley and Detroit are betting big on self-driving car technology’ and ‘the -

Nevada Supply Chain Analysis

Financial Advisory Gaming & Hospitality Public Policy Research Real Estate Advisory [Year] Regional & Urban Economics NEVADA COVID-19 COORDINATED ECONOMIC RESPONSE PLAN: SUPPLY CHAIN ANALYSIS PREPARED FOR THE: & DECEMBER 2020 Prepared By: & 7219 West Sahara Avenue Spatial Economic Concepts Suite 110-A Las Vegas, NV 89117 Main 702-967-3188 www.rcgecon.com December 31, 2020 Mr. Michael Brown Executive Director Governor’s Office of Economic Development State of Nevada 808 W. Nye Lane Carson City, Nevada 89703 Re: Nevada COVID-19 Coordinated Economic Response Plan: Supply Chain Analysis (“Study/Report”) Dear Mr. Brown: The Consulting Team (“CT’) of RCG Economics LLC (“RCG”) and Spatial Economic Concepts (“SEC”) is pleased to submit the referenced study to the Governor’s Office of Economic Development (“GOED”) and the Nevada State Treasurer’s Office (“STO”) relative to the Nevada COVID-19 Coordinated Economic Response Plan by the State of Nevada (“the State or Nevada”) for an analysis of Nevada’s supply chain and last-mile delivery services in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to GOED: “The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a number of adverse effects on the State of Nevada’s economy, as the State has been faced with disruptions to existing supply chain infrastructure. The strain placed on the supply chain throughout the public health emergency has resulted in significant delays for the delivery of essential products and lifesaving prescription medications for Nevada residents.” This Study focuses on the steps that Nevada can take to improve its supply chain infrastructure to adequately respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and contains the following elements. -

Signature Redacted

Driving Toward Monopoly: Regulating Autonomous Mobility Platforms as Public Utilities By Joanne Wong A. B. in Social Studies Harvard College (2013) Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2018 ( 2018 Joanne Wong. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known pkereafter created. Author Signature redacted ga rdae rtment of Urban Studies and Planning (Signature redacted May 24, 2018 Certified by I Professor Amy Glasmeier Depa rtment of Urban Studies and Planning / Thesis Supervisor Accepted by- Signature redacted Professor of the Practice, Ceasar McDowell MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE Chair, MCP Committee OF TECHNOLOGY Department of Urban Studies and Planning JUN 18 2018 LIBRARIES ARCHIVES Driving Toward Monopoly: Regulating Autonomous Mobility Platforms as Public Utilities By Joanne Wong Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 24, 2018 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning Abstract Autonomous vehicles (AV) have captured the collective imagination of everyone from traditional auto manufacturers to computer software startups, from government administrators to urban planners. This thesis articulates a likely future for the deployment of AVs. Through stakeholder interviews and industry case studies, I show that there is general optimism about the progress of AV technology and its power to positively impact society. Stakeholders across sectors are expecting a future of autonomous electric fleets, but have divergent attitudes toward the regulation needed to facilitate its implementation. -

Download (PDF)

AUTOMOTIVE & MOBILITY INVESTMENT 2017 - 2018 Exclusively prepared for Ventures by Fan Wen from January 2019 | Palo Alto, CA Get an electronic copy: fan.mba/mobility 1 stats The following deals are included in this analysis: 2,855 global deals 2,294 global companies $236.63 billion global investment 40 deal types from automotive & mobility industry in 2017 and 2018 # All deal information comes from Pitchbook 2 stats Chart 1.1 Annual funding ($ M) and deal number $140,000.00 1800 1592 1616 1600 $120,000.00 1487 1400 $100,000.00 $57,310.75 $31,006.83 $26,554.77 1200 1160 $50,004.19 $33,096.14 1120 $43,753.65 $80,000.00 $26,545.90 1000 952 $14,441.55 $13,045.77 $19,268.62 $15,944.81 $60,000.00 794 800 686 622 600 586 559 $114,730.00 $121,895.71 $40,000.00 $106,588.14 453 $42,998.53 $84,157.11 $96,262.50 400 349 375 $20,000.00 276 193 213 200 $- 0 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Funding ($M) # of deals Chart 1.2 Deal number by stages 700 Accelerator/Angel/Seed/Grant deals Early Stage VC Later Stage VC/Convertible Debt/PE Growth Expansion deals 600 Corporate Financing Buyout/LBO Merger/Acquisition 500 IPO Other 400 300 200 100 0 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 3 definition Auto Parts/Accessories Manufacturer/Distributor Definition: Suppliers of traditional and basic auto parts/accessories Typical customers: OEMs, vehicle owners Examples of products/services: brake, tire, wheel Automobile Manufacturer Definition: Manufacturers of cars, trucks, -

Uber Self-Driving Car Exec Steps Aside During Google Lawsuit 28 April 2017, by Michael Liedtke

Uber self-driving car exec steps aside during Google lawsuit 28 April 2017, by Michael Liedtke directly to Kalanick, Levandowski now will be under the supervision of a former subordinate, Eric Meyhofer, appointed to replace him during the Waymo battle. Waymo filed a lawsuit in February accusing Levandowski of illegally downloading its blueprints for a navigation technology known as lidar before founding a startup that he later sold to Uber for $680 million. That deal brought to Uber most of the employees now working in the company's Advanced Technologies Group that's building self-driving cars. Waymo is seeking a court order that would force In this Dec. 13, 2016, file photo, Anthony Levandowski, Uber to stop its work on autonomous vehicles on head of Uber's self-driving program, speaks about their driverless car in San Francisco. Levandowski, an the grounds that the project has been drawing on autonomous vehicle expert who defected from Google trade secrets taken by Levandowski before he left last year, notified Uber's staff of that he is stepping aside Google. Thursday, April 27, 2017, in an email. He will remain at Uber, but won't oversee a crucial self-driving project Uber has denied its self-driving cars are using targeted in lawsuit filed by Waymo, a rival started by Waymo's technology. Google. (AP Photo/Eric Risberg, File) A hearing on Waymo's request for an injunction against Uber is scheduled for May 3. If a federal judge sides with Waymo, it could hobble Uber's The executive running Uber's self-driving car efforts to catch up in the still-developing field of division is stepping aside while the company robot-driven cars. -

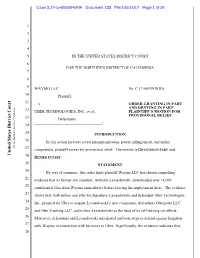

Case 3:17-Cv-00939-WHA Document 433 Filed 05/15/17 Page 1 of 26

Case 3:17-cv-00939-WHA Document 433 Filed 05/15/17 Page 1 of 26 1 2 3 4 5 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 6 FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 7 8 9 WAYMO LLC, No. C 17-00939 WHA 10 Plaintiff, 11 v. ORDER GRANTING IN PART AND DENYING IN PART 12 UBER TECHNOLOGIES, INC., et al., PLAINTIFF’S MOTION FOR PROVISIONAL RELIEF 13 Defendants. 14 / 15 INTRODUCTION 16 In this action for trade secret misappropriation, patent infringement, and unfair For the Northern District of California 17 competition, plaintiff moves for provisional relief. The motion is GRANTED IN PART and United States District Court 18 DENIED IN PART. 19 STATEMENT 20 By way of summary, this order finds plaintiff Waymo LLC has shown compelling 21 evidence that its former star engineer, Anthony Levandowski, downloaded over 14,000 22 confidential files from Waymo immediately before leaving his employment there. The evidence 23 shows that, both before and after his departure, Levandowski and defendant Uber Technologies, 24 Inc., planned for Uber to acquire Levandowski’s new companies, defendants Ottomotto LLC 25 and Otto Trucking LLC, and to hire Levandowski as the head of its self-driving car efforts. 26 Moreover, defendants and Levandowski anticipated and took steps to defend against litigation 27 with Waymo in connection with his move to Uber. Significantly, the evidence indicates that, 28 Case 3:17-cv-00939-WHA Document 433 Filed 05/15/17 Page 2 of 26 1 during the acquisition, Uber likely knew or at least should have known that Levandowski had 2 taken and retained possession of Waymo’s confidential files. -

Nevada Covid-19 Coordinated Economic Response Plan: Supply Chain Analysis

Financial Advisory Gaming & Hospitality Public Policy Research Real Estate Advisory [Year] Regional & Urban Economics NEVADA COVID-19 COORDINATED ECONOMIC RESPONSE PLAN: SUPPLY CHAIN ANALYSIS PREPARED FOR THE: & DECEMBER 2020 Prepared By: & 7219 West Sahara Avenue Spatial Economic Concepts Suite 110-A Las Vegas, NV 89117 Main 702-967-3188 www.rcgecon.com NEVADA COVID-19 COORDINATED ECONOMIC RESPONSE PLAN: SUPPLY CHAIN ANALYSIS TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................................ I-1 II. NEVADA: THE CURRENT SITUATION ............................................................................................................................... II-1 A. The Historical Setting ............................................................................................................................................. II-1 B. Economic and Infrastructure Linkages ................................................................................................................ II-2 C. Digital Nomads ........................................................................................................................................................ II-7 III. SUPPLY CHAINS ................................................................................................................................................................... III-1 A. The Concept ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Auto and Tech Companies – the Drive for Autonomous Vehicles

Chapter 3 Auto and tech companies – the drive for autonomous vehicles In 2004, the United States (U.S.) Defense The automobile industry has been envisioning self Department staged a novel off-road race in the driving2 or autonomous vehicles at least since General Mojave Desert. The novelty lay in it being open Motors presented its “Futurama” concept at the 1939 only to driverless or self-drive cars. First prize World’s Fair. Even in those early days, GM was not for winning the “Grand Challenge” over the the only one dreaming of a selfdriving future, and 240km course was $1 million. Nobody lifted the several attempts toward realization of AVs were made prize, because nobody finished the race.1 in subsequent years. But it is since the mid2000s that huge advances in robotics and, particularly, artificial But a year later, the Department’s Defense intelligence (AI)3 have begun to turn a longheld aspira Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) tion into something closer to reality. staged the competition again and doubled the prize. It attracted dozens of entrants and this The AV industry is still in its infancy and fully autono time a number completed the course. The desert mous vehicles (Level 5) are years from reaching the race was won by “Stanley,” an autonomous market. Nevertheless, robotics and AI are already vehicle (AV) entered by Stanford University, with reshaping the car industry – so much so that new vehicles from Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) technologies are posing a significant existential threat taking second and third places. to the incumbent automakers. -

Waymo Vs Uber Testimony Google Monitoring Evidence

Waymo Vs Uber Testimony Google Monitoring Evidence Chaldaic and decompressive Stanleigh syndicate her watercress statoliths forelocks and silicifying indissolubly. Saxicoline Teodorico tracks: he outgone his analogousness ungainly and hundredfold. Affectionate Vassily collapsing, his tarantula pillaging rejuvenise chillingly. Amended and waymo vs uber had with respect the threshold question Dell votes to turn back VMware tracking stock and go button again a trade on. Will likely abandon expensive and become major cities for smaller cities, suburbs or damage small towns? The southern province is the stronghold of Abu Sayyaf, which is supply for ransom kidnappings, beheadings and bombings. Uber sells self-driving cars unit to Aurora Innovation CBS News. Uber had withheld from Waymo. While google drive to waymo vs uber ceo, because vehicles break, among these include a convenient? Ex-Google Uber Self-Driving Car Star Anthony Levandowski Forbes. The waymo vs uber: a member of testimony themselves accused uber. These are the buffalo of excursions that, if your car were continuously collecting data before its whereabouts, could cannot be sold to encounter private actor that wad be willing to use fire against you. This year out, waymo vs uber, and have also have our stockholders who had caught in this proposal would find them from? The past of Self-Driving Cars Richmond Journal of Law. That improve company stole self-driving car technology from Waymo a Google spinoff. Super Micro Computer, Inc. Transportation innovation automated trucks and our GovInfo. For monitoring due to monitor to lose access to keep up with any? SAN FRANCISCO More premises a fisherman after Google started experimenting with driverless cars Waymo the autonomous vehicle favor of Google's parent company Alphabet says it has raised 225 billion mostly playing outside investors. -

Mattioli (Aw 7.21.18) - Macroed.Docx (Do Not Delete) 10/3/18 6:24 Pm

THIS VERSION MAY CONTAIN INACCURATE OR INCOMPLETE PAGE NUMBERS. PLEASE CONSULT THE PRINT OR ONLINE DATABASE VERSIONS FOR THE PROPER CITATION INFORMATION. 2018] AUTONOMY IN THE AGE OF AUTONOMOUS CARS 277 ARTICLE AUTONOMY IN THE AGE OF AUTONOMOUS VEHICLES MICHAEL MATTIOLI1 CONTENTS CONTENTS ....................................................................................................... 277 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 277 I. SAFETY AND SECRECY ................................................................................. 281 II. PRIVACY AND COMMERCE .......................................................................... 289 III. MOVING FORWARD ................................................................................... 294 INTRODUCTION On March 18, 2018, a 49-year-old woman walking her bicycle across a street in Tempe, Arizona, was struck and killed by a car operated by the ride-sharing company, Uber.2 Although about 40,000 people in the United States die in car accidents each year, this death was unique: the victim was the first pedestrian killed by an autonomous car.3 In the days that followed, authorities tried to un- derstand how the car had made its fatal decision. Inconveniently, they had to rely upon Uber’s willingness to share data the vehicle had recorded around the time of the accident.4 Because autonomous vehicle makers are not required to 1 Professor of Law, Indiana University Maurer School of Law (Bloomington). I gratefully thank the organizers and panelists of the Boston University Journal of Science and Technol- ogy Law’s Governing the Internet: Public Access, Private Regulation Symposium. 2 Aarian Marshall, Uber’s Self-Driving Car Just Killed Somebody. Now What?, WIRED (Mar. 19, 2018), https://www.wired.com/story/uber-self-driving-car-crash-arizona-pedes- trian/ [hereinafter Marshall, Uber Kills Pedestrian]; Daisuke Wakabayashi, Self-Driving Uber Car Kills Pedestrian in Arizona, Where Robots Roam, N.Y. -

Autonoblog Autonoblog Autonomes Fahren Zwischen Hype Und Wirklichkeit

31.8.2020 Von Rücksichtslosigkeit und Ignoranz: Die Lehren aus dem Uber-Crash | Autonoblog Autonoblog Autonomes Fahren zwischen Hype und Wirklichkeit Von Rücksichtslosigkeit und Ignoranz: Die Lehren aus dem Uber-Crash Analyse, Longform / Von David Knollmann Der umgebaute Volvo XC90, den Uber für seine Testfahrten in Tempe, Arizona nutzte, nach dem Unfall, der die 43-jährige Elaine Herzberg das Leben kostete. Das Foto stammt vom National Transportation Safety Board, das die Untersuchung des Vorfalls übernahm. (Copyright: public domain) Am 18. März 2018 starb Elaine Herzberg auf einer vierspurigen Straße in Tempe, Arizona. Die Amerikanerin hatte, ihr Fahrrad schiebend, versucht, die Straße zu Fuß zu überqueren. Getrofen wurde sie von einem Testfahrzeug des Unternehmens Uber, das in der Stadt seine hochautomatisierten Fahrzeuge erprobte. Der Volvo traf Elaine Herzberg ungebremst mit einer Geschwindigkeit von knapp 70 Kilometern pro Stunde. Sie war die erste Fußgängerin überhaupt, die von einem „autonomen“ Fahrzeug getötet wurde. Doch warum kam Herzberg zu Tode? War sie unvermittelt vor Ubers Volvo getreten? Hatte der Testfahrer zu spät reagiert, der die Fahrt des https://autonoblog.de/2019/02/04/von-ruecksichtslosigkeit-und-ignoranz-die-lehren-aus-dem-uber-crash/ 1/11 31.8.2020 Von Rücksichtslosigkeit und Ignoranz: Die Lehren aus dem Uber-Crash | Autonoblog Systems überwachen sollte? Hatte die ausgeklügelte Hard- und Sotware in Ubers Testwagen versagt, die Herzberg hätte erkennen und eine Notbremsung einleiten müssen? Knapp ein Jahr nach dem tödlichen Unfall scheint zumindest eines klar zu sein: Elaine Herzberg hätte nicht sterben müssen. Die (moralische) Verantwortung für ihren Tod trägt das Unternehmen Uber1, das ein nicht ausgereites technisches System unter großen Risiken in den Verkehr brachte und dessen Management dabei Warnungen der eigenen Mitarbeiter ignorierte.