Teaching American Literature: a Journal of Theory and Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Knotted Tails a Supplemental Storyline for Mask of the Oni the KNOTTED TAILS

the knotted tails a supplemental storyline for Mask of the Oni THE KNOTTED TAILS The Knotted Tails Part One: This is an optional bonus storyline that may be played within Mask of the Oni, an adventure for the Legend of the Storyline Background Five Rings Roleplying Game. Encounters are designed for If played during Mask of the Oni, the GM can use this a party of four PCs of rank 2, though these can be adjust- as an opportunity to prepare the players for the dangers ed for parties of any size and ranks by using Gauging an they will face once inside the castle. As the PCs piece Encounter on page 310 of the core rulebook. together the Knotted Tails’ version of the past, they may The Knotted Tails takes place before the PCs reach uncover clues about the history of the Hiruma and their Shiro Hiruma, but after the optional encounter “The fate. If played during a different Shadowlands adventure, Lost” on page 15 of that adventure. Alternatively, it can the PCs have an opportunity to make useful allies––if they be adapted for use within any campaign in the Shad- can find and slay the threat that is on the hunt for nezumi owlands. Whether PCs are involved in Mask of the Oni blood. Either way, the PCs can rest in the relatively safe or not, these encounters allow them to meet and learn territory of the tribe and gain useful supplies, valuable about the human-sized, rat-like nezumi and discovr what information, and the promise of nezumi aid in the future. -

Cyberpunking a Library

Cyberpunking a Library Collection assessment and collection Leanna Jantzi, Neil MacDonald, Samantha Sinanan LIBR 580 Instructor: Simon Neame April 8, 2010 “A year here and he still dreamed of cyberspace, hope fading nightly. All the speed he took, all the turns he’d taken and the corners he’d cut in Night City, and he’d still see the matrix in his sleep, bright lattices of logic unfolding across that colorless void.” – Neuromancer, William Gibson 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Description of Subject ....................................................................................................................................... 3 History of Cyberpunk .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Themes and Common Motifs....................................................................................................................................... 3 Key subject headings and Call number range ....................................................................................................... 4 Description of Library and Community ..................................................................................................... -

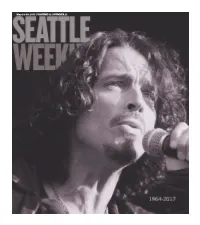

VOLUME 42 | NUMBER 21 Hen Chris Cornell Entered He Shrugged

May 24-30, 2017 | VOLUME 42 | NUMBER 21 hen Chris Cornell entered He shrugged. He spoke in short bursts of at a room, the air seemed to syllables. Soundgarden was split at the time, hum with his presence. All and he showed no interest in getting the eyes darted to him, then band back together. He showed little interest danced over his mop of in many of my questions. Until I noted he curls and lanky frame. He appeared to carry had a pattern of daring creative expression himself carelessly, but there was calculation outside of Soundgarden: Audioslave’s softer in his approach—the high, loose black side; bluesy solo eorts; the guitar-eschew- boots, tight jeans, and impeccable facial hair ing Scream with beatmaker Timbaland. his standard uniform. He was a rock star. At this, Cornell’s eyes sharpened. He He knew it. He knew you knew it. And that sprung forward and became fully engaged. didn’t make him any less likable. When he He got up and brought me an unsolicited left the stage—and, in my case, his Four bottled water, then paced a bit, talking all Seasons suite following a 2009 interview— the while. About needing to stay unpre- that hum leisurely faded, like dazzling dictable. About always trying new things. sunspots in the eyes. He told me that he wrote many songs “in at presence helped Cornell reach the character,” outside of himself. He said, “I’m pinnacle of popular music as front man for not trying to nd my musical identity, be- Soundgarden. -

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

Nudedragons to King Animal — the First Ever Fan-Based Compilation Photobook — Is Now Available!

PHOTOFANTASM SOUNDGARDEN: NUDEDRAGONS TO KING ANIMAL — THE FIRST EVER FAN-BASED COMPILATION PHOTOBOOK — IS NOW AVAILABLE! The only book ever created by the fans for any high-profile band, Photofantasm Soundgarden is dedicated to rock pioneers Soundgarden. It features commentary and recollections from fellow artists, the music press, and other notable contributors. SEATTLE, May 18, 2015 /PRNewswire/ Photofantasm Soundgarden: Nudedragons to King Animal highlights the Seattle band’s rebirth via hundreds of pages’ worth of photographs, graphic art, anecdotes, interviews, and reviews. In a truly collaborative effort, fans, artists, musicians, authors, photographers, and other notable personalities all help chronicle Soundgarden's performances across the globe from 2010 to 2013. To quote Everybody Loves Our Town: An Oral History of Grunge author Mark Yarm in his foreword to Photofantasm Soundgarden, the book is “by the fans, for the fans”—the book boasts more than 300 contributors from more than 30 countries on six continents—and captures what promises to be just the beginning of a very long second chapter! Much like classic vinyl, Photofantasm Soundgarden is a quality, limited-edition collector's item (only 1,000 copies) meant to be savored by the fans (and the band itself) for years to come. The heart of this book is a section devoted to the loving memory of an extraordinary friend and Soundgarden fan who courageously fought cancer. All net proceeds will go to Canary Foundation, the first and only foundation in the world solely dedicated to the funding of early cancer-detection solutions. Photofantasm totals 592 pages, much of it exclusive content. -

Novel Planning Kit Version 03.2020.11

Novel Planning Kit Version 03.2020.11 Created by Terry J. Benton Dear Writers, I started my first manuscript over 10 years ago, and it would take seven more manuscripts and one novella, countless tears and frustration, and lots of effort devoted to studying craft and learning as much as possible before I signed with an agent. Throughout this journey, I’ve enjoyed giving back to the community and helping those who are coming up through the query trenches behind me. I created this Novel Planning Kit from a combination of useful exercises I’ve employed over the last decade to successfully plan fiction novels with the hope that it will assist newer writers on their paths to publication and beyond. There are a plethora of ways to plan, write, and revise a manuscript, and this is just one of thousands of paths available to you—and may not suit your unique needs. I urge you to continue researching widely to find the methods that work best for you and your process. This kit is intended as a FREE resource for writers. Simply print the kit in its entirety and complete the worksheets to begin planning your new novel. Good luck and happy writing! Terry B. | https://www.tjbenton.com | @terryjbenton | @icecreamvicelord TABLE OF CONTENTS Exercise 1: Story Setup Page 2 Build the three cornerstones of your story: hook, challenge, and theme Exercise 2: Conflict Page 3 Identify internal and external conflict for your protagonist, as well as conflicts with minor characters Exercises 3A & 3B: Character Dossier Pages 4 & 5 Develop substantial background for your main and supporting characters Exercise 4: Plot Development Page 6 & 7 Brainstorm major plot points and plot threads for your story Exercise 5: Act Structuring Page 8 Structure your story’s plot across three acts Exercise 6: Pitch Draft Page 9 Draft the first cut of your pitch (or query) Recurring Exercise: Scene Planning Page 10 Recurring exercise for planning and structuring scenes Appendix: Helpful Resources Page 11 Additional helpful paid and free resources Copyright © 2020 by Terry J. -

The Purloined Life of Edgar Allan Poe by Jeffrey Steinberg Edgar Allan Poe

Click here for Full Issue of Fidelio Volume 15, Number 1-2, Spring-Summer 2006 EDGAR ALLAN POE and the Spirit of the American Republic The Purloined Life Of Edgar Allan Poe by Jeffrey Steinberg Edgar Allan Poe great deal of what people think they know about dark side, and the dark side is that most really creative Edgar Allan Poe, is wrong. Furthermore, there geniuses are insane, and usually something bad comes of Ais not that much known about him—other than them, because the very thing that gives them the talent to that people have read at least one of his short stories, or be creative is what ultimately destroys them. poems; and it’s common even today, that in English liter- And this lie is the flip-side of the argument that most ature classes in high school—maybe upper levels of ele- people don’t have the “innate talent” to be able to think; mentary school—you’re told about Poe. And if you ever most people are supposed to accept the fact that their lives got to the point of being told something about Poe as an are going to be routine, drab, and ultimately insignificant actual personality, you have probably heard some sum- in the long wave of things; and when there are people mary distillation of the slanders about him: He died as a who are creative, we always think of their creativity as drunk; he was crazy; he was one of these people who occurring in an attic or a basement, or in long walks demonstrate that genius and creativity always have a alone in the woods; that creativity is not a social process, but something that happens in the minds of these ran- __________ domly born madmen or madwomen. -

SFRA Newsletter 259/260

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 12-1-2002 SFRA ewN sletter 259/260 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 259/260 " (2002). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 76. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/76 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #2Sfl60 SepUlec.JOOJ Coeditors: Chrlis.line "alins Shelley Rodrliao Nonfiction Reviews: Ed "eNnliah. fiction Reviews: PhliUp Snyder I .....HIS ISSUE: The SFRAReview (ISSN 1068- 395X) is published six times a year Notes from the Editors by the Science Fiction Research Christine Mains 2 Association (SFRA) and distributed to SFRA members. Individual issues are not for sale. For information about SFRA Business the SFRA and its benefits, see the New Officers 2 description at the back of this issue. President's Message 2 For a membership application, con tact SFRA Treasurer Dave Mead or Business Meeting 4 get one from the SFRA website: Secretary's Report 1 <www.sfraorg>. 2002 Award Speeches 8 SUBMISSIONS The SFRAReview editors encourage Inverviews submissions, including essays, review John Gregory Betancourt 21 essays that cover several related texts, Michael Stanton 24 and interviews. Please send submis 30 sions or queries to both coeditors. -

Chart Book Template

Real Chart Page 1 become a problem, since each track can sometimes be released as a separate download. CHART LOG - F However if it is known that a track is being released on 'hard copy' as a AA side, then the tracks will be grouped as one, or as soon as known. Symbol Explanations s j For the above reasons many remixed songs are listed as re-entries, however if the title is Top Ten Hit Number One hit. altered to reflect the remix it will be listed as would a new song by the act. This does not apply ± Indicates that the record probably sold more than 250K. Only used on unsorted charts. to records still in the chart and the sales of the mix would be added to the track in the chart. Unsorted chart hits will have no position, but if they are black in colour than the record made the Real Chart. Green coloured records might not This may push singles back up the chart or keep them around for longer, nevertheless the have made the Real Chart. The same applies to the red coulered hits, these are known to have made the USA charts, so could have been chart is a sales chart and NOT a popularity chart on people’s favourite songs or acts. Due to released in the UK, or imported here. encryption decoding errors some artists/titles may be spelt wrong, I apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. The chart statistics were compiled only from sales of SINGLES each week. Not only that but Date of Entry every single sale no matter where it occurred! Format rules, used by other charts, where unnecessary and therefore ignored, so you will see EP’s that charted and other strange The Charts were produced on a Sunday and the sales were from the previous seven days, with records selling more than other charts. -

Irish Gothic Fiction

THE ‘If the Gothic emerges in the shadows cast by modernity and its pasts, Ireland proved EME an unhappy haunting ground for the new genre. In this incisive study, Jarlath Killeen shows how the struggle of the Anglican establishment between competing myths of civility and barbarism in eighteenth-century Ireland defined itself repeatedly in terms R The Emergence of of the excesses of Gothic form.’ GENCE Luke Gibbons, National University of Ireland (Maynooth), author of Gaelic Gothic ‘A work of passion and precision which explains why and how Ireland has been not only a background site but also a major imaginative source of Gothic writing. IRISH GOTHIC Jarlath Killeen moves well beyond narrowly political readings of Irish Gothic by OF IRISH GOTHIC using the form as a way of narrating the history of the Anglican faith in Ireland. He reintroduces many forgotten old books into the debate, thereby making some of the more familiar texts seem suddenly strange and definitely troubling. With FICTION his characteristic blend of intellectual audacity and scholarly rigour, he reminds us that each text from previous centuries was written at the mercy of its immediate moment as a crucial intervention in a developing debate – and by this brilliant HIST ORY, O RIGI NS,THE ORIES historicising of the material he indicates a way forward for Gothic amidst the ruins of post-Tiger Ireland.’ Declan Kiberd, University of Notre Dame Provides a new account of the emergence of Irish Gothic fiction in the mid-eighteenth century FI This new study provides a robustly theorised and thoroughly historicised account of CTI the beginnings of Irish Gothic fiction, maps the theoretical terrain covered by other critics, and puts forward a new history of the emergence of the genre in Ireland. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 12-1-2019 British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century Beverley Rilett University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Rilett, Beverley, "British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century" (2019). Zea E-Books. 81. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/81 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century A Selection for College Students Edited by Beverley Park Rilett, PhD. CHARLOTTE SMITH WILLIAM BLAKE WILLIAM WORDSWORTH SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE GEORGE GORDON BYRON PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY JOHN KEATS ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING ALFRED TENNYSON ROBERT BROWNING EMILY BRONTË GEORGE ELIOT MATTHEW ARNOLD GEORGE MEREDITH DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI CHRISTINA ROSSETTI OSCAR WILDE MARY ELIZABETH COLERIDGE ZEA BOOKS LINCOLN, NEBRASKA ISBN 978-1-60962-163-6 DOI 10.32873/UNL.DC.ZEA.1096 British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century A Selection for College Students Edited by Beverley Park Rilett, PhD. University of Nebraska —Lincoln Zea Books Lincoln, Nebraska Collection, notes, preface, and biographical sketches copyright © 2017 by Beverly Park Rilett. All poetry and images reproduced in this volume are in the public domain. ISBN: 978-1-60962-163-6 doi 10.32873/unl.dc.zea.1096 Cover image: The Lady of Shalott by John William Waterhouse, 1888 Zea Books are published by the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries.