A History of Video Game Violence and the Legacy of Death Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Westworld

“We Don’t Know Exactly How They Work”: Making Sense of Technophobia in 1973 Westworld, Futureworld, and Beyond Westworld Stefano Bigliardi Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane - Morocco Abstract This article scrutinizes Michael Crichton’s movie Westworld (1973), its sequel Futureworld (1976), and the spin-off series Beyond Westworld (1980), as well as the critical literature that deals with them. I examine whether Crichton’s movie, its sequel, and the 1980s series contain and convey a consistent technophobic message according to the definition of “technophobia” advanced in Daniel Dinello’s 2005 monograph. I advance a proposal to develop further the concept of technophobia in order to offer a more satisfactory and unified interpretation of the narratives at stake. I connect technophobia and what I call de-theologized, epistemic hubris: the conclusion is that fearing technology is philosophically meaningful if one realizes that the limitations of technology are the consequence of its creation and usage on behalf of epistemically limited humanity (or artificial minds). Keywords: Westworld, Futureworld, Beyond Westworld, Michael Crichton, androids, technology, technophobia, Daniel Dinello, hubris. 1. Introduction The 2016 and 2018 HBO series Westworld by Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy has spawned renewed interest in the 1973 movie with the same title by Michael Crichton (1942-2008), its 1976 sequel Futureworld by Richard T. Heffron (1930-2007), and the short-lived 1980 MGM TV series Beyond Westworld. The movies and the series deal with androids used for recreational purposes and raise questions about technology and its risks. I aim at an as-yet unattempted comparative analysis taking the narratives at stake as technophobic tales: each one conveys a feeling of threat and fear related to technological beings and environments. -

Why Call Them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960S Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK

Why Call them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960s Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK Preface In response to the recent increased prominence of studies of "cult movies" in academic circles, this essay aims to question the critical usefulness of that term, indeed the very notion of "cult" as a way of talking about cultural practice in general. My intention is to inject a note of caution into that current discourse in Film Studies which valorizes and celebrates "cult movies" in particular, and "cult" in general, by arguing that "cult" is a negative symptom of, rather than a positive response to, the social, cultural, and cinematic conditions in which we live today. The essay consists of two parts: firstly, a general critique of recent "cult movies" criticism; and, secondly, a specific critique of the term "cult movies" as it is sometimes applied to 1960s American independent biker movies -- particularly films by Roger Corman such as The Wild Angels (1966) and The Trip (1967), by Richard Rush such as Hell's Angels on Wheels (1967), The Savage Seven, and Psych-Out (both 1968), and, most famously, Easy Rider (1969) directed by Dennis Hopper. Of course, no-one would want to suggest that it is not acceptable to be a "fan" of movies which have attracted the label "cult". But this essay begins from a position which assumes that the business of Film Studies should be to view films of all types as profoundly and positively "political", in the sense in which Fredric Jameson uses that adjective in his argument that all culture and every cultural object is most fruitfully and meaningfully understood as an articulation of the "political unconscious" of the social and historical context in which it originates, an understanding achieved through "the unmasking of cultural artifacts as socially symbolic acts" (Jameson, 1989: 20). -

Gesamtkatalog BRD (Regionalcode 2) Spielfilme Nr. 94 (Mai 2010)

Gesamtkatalog BRD (Regionalcode 2) Spielfilme -Kurzübersicht- Detaillierte Informationen finden Sie auf unserer Website und in unse- rem 14tägigen Newsletter Nr. 94 (Mai 2010) LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS Talstr. 11 - 70825 Korntal Tel.: (0711) 83 21 88 - Fax: (0711) 8 38 05 18 INTERNET: www.laserhotline.de e-mail: [email protected] Katalog DVD BRD (Spielfilme) Nr. 94 Mai 2010 (500) Days of Summer 10 Dinge, die ich an dir 20009447 25,90 EUR 12 Monkeys (Remastered) 20033666 20,90 EUR hasse (Jubiläums-Edition) 20009576 25,90 EUR 20033272 20,90 EUR Der 100.000-Dollar-Fisch (K)Ein bisschen schwanger 20022334 15,90 EUR 12 Uhr mittags 20032742 18,90 EUR Die 10 Gebote 20000905 25,90 EUR 20029526 20,90 EUR 1000 - Blut wird fließen! (Traum)Job gesucht - Will- 20026828 13,90 EUR 12 Uhr mittags - High Noon kommen im Leben Das 10 Gebote Movie (Arthaus Premium, 2 DVDs) 20033907 20,90 EUR 20032688 15,90 EUR 1000 Dollar Kopfgeld 20024022 25,90 EUR 20034268 15,90 EUR .45 Das 10 Gebote Movie Die 120 Tage von Bottrop 20024092 22,90 EUR (Special Edition, 2 DVDs) Die 1001 Nacht Collection – 20016851 20,90 EUR 20032696 20,90 EUR Teil 1 (3 DVDs) .com for Murder 20023726 45,90 EUR 13 - Tzameti (k.J.) 20006094 15,90 EUR 10 Items or Less - Du bist 20030224 25,90 EUR wen du triffst 101 Dalmatiner (Special [Rec] (k.J.) 20024380 20,90 EUR Edition) 13 Dead Men 20027733 18,90 EUR 20003285 25,90 EUR 20028397 9,90 EUR 10 Kanus, 150 Speere und [Rec] (k.J.) drei Frauen 101 Reykjavik 13 Dead Men (k.J.) 20032991 13,90 EUR 20024742 20,90 EUR 20006974 25,90 EUR 20011131 20,90 EUR 0 Uhr 15 Zimmer 9 Die 10 Regeln der Liebe 102 Dalmatiner 13 Geister 20028243 tba 20005842 16,90 EUR 20003284 25,90 EUR 20005364 16,90 EUR 00 Schneider - Jagd auf 10 Tage die die Welt er- Das 10te Königreich (Box 13 Semester - Der frühe Nihil Baxter schütterten Set) Vogel kann mich mal 20014776 20,90 EUR 20008361 12,90 EUR 20004254 102,90 EUR 20034750 tba 08/15 Der 10. -

The BG News April 15, 1999

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-15-1999 The BG News April 15, 1999 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News April 15, 1999" (1999). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6484. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6484 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ■" * he BG News Women rally to 'take back the night' sexual assault. istration vivors, they will be able to relate her family. By WENDY SUTO Celesta Haras/ti, a resident of buildings, rain to parts of her story, Kissinger "The more I tell my story, the The BG News BG and a W4W member, said the or shine. The said. less shame and guilt I feel," Kissinger said. "For my situa- Women (and some men) will rally is about issues that are con- keynote "When I decided to disclose tion, I'm glad I didn't tell my take to the streets tonight, pro- sidered taboo by society, such as speaker, my sexual abuse to my family, I parents right away because I claiming a public statement in an rape and incest. She has attended Kendel came out of the closet complete- think it would have been a worse attempt to "Take Back the Night" several TBTN marches at the Kissinger, a ly," Kissinger said. -

2012-Loft-Film-Fest-Program

Festival Parties Join us as we cut the ribbon on our brand-new third screen! Ribbon cutting Friday November 9 at 5:00pm Open House 5:00 - 6:30pm Join the Loft staff, Board of Directors and local officials as we un- veil our new third screen (or what we affectionately call Screen 3)! You’ll be the first to step inside this new space for a behind-the- Loft Film Fest 2012 scenes tour! Join us for a champagne toast as we celebrate a job well done by an incredible team of dedicated people! loftfilmfest.com We will recognize the donors who made this phase of the project Inspired by film’s unique ability to entertain, engage, challenge and possible and we will especially honor those who have given their illuminate, The Loft Cinema will present its third annual international name to key parts of the project, including Bob Oldfather and film festival fromNovember 8th – 15th, 2012. Bookmans for the 3-D technology in Screen 3! Honoring Tucson’s richly diverse cultural community, The Loft Film Fest will present foreign films, documentaries and U.S. indies in a cin- You’re invited to The Loft Cinema’s ematic celebration of storytelling from around the world. 40th birthday party! The Loft Film Fest is an eight-day showcase of exclusive, one-time-only Friday November 15 from 5:30 - 7:30pm screenings and will feature: Yes, we know we don’t look 40, but The Loft is celebrating four • Festival favorites from Cannes, Sundance, Telluride, and more! decades of great film in Tucson! • Lively Q&A’s with talented filmmakers and actors Join us as we honor the last 40 years and toast the next 40! • Exciting retrospective screenings Where: The Lodge on the Desert • New international cinema 306 North Alvernon Way • Edgy Late Night movies When: 5:30 - 7:30pm, Thursday, November 15 (the actual 10th an- • Stimulating shorts from the filmmakers of tomorrow niversary of our purchase of The Loft as a nonprofit in 2002!) At the Loft Film Fest, audiences experience world-class film festival Who: Everyone! Loft Film Fest passholders get in free. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games ( Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack ( Arcade, TG16) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1943: Kai (TG16) 12. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 13. 1944: The Loop Master ( Arcade) 14. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 15. 19XX: The War Against Destiny ( Arcade) 16. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge ( Arcade) 17. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 18. 2020 Super Baseball ( Arcade, SNES) 19. 21-Emon (TG16) 20. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 21. 3 Count Bout ( Arcade) 22. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 23. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 24. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 25. 3-D WorldRunner (NES) 26. 3D Asteroids (Atari 7800) 27. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games (Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack (TG16, Arcade) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1942 (Revision B) (Arcade) 12. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) (Arcade) 13. 1943: Kai (TG16) 14. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 15. 1944: The Loop Master (Arcade) 16. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 17. 19XX: The War Against Destiny (Arcade) 18. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge (Arcade) 19. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 20. 2020 Super Baseball (SNES, Arcade) 21. 21-Emon (TG16) 22. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 23. 3 Count Bout (Arcade) 24. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 25. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 26. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 27. -

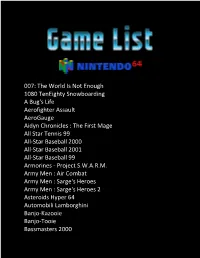

007: the World Is Not Enough 1080 Teneighty Snowboarding a Bug's

007: The World Is Not Enough 1080 TenEighty Snowboarding A Bug's Life Aerofighter Assault AeroGauge Aidyn Chronicles : The First Mage All Star Tennis 99 All-Star Baseball 2000 All-Star Baseball 2001 All-Star Baseball 99 Armorines - Project S.W.A.R.M. Army Men : Air Combat Army Men : Sarge's Heroes Army Men : Sarge's Heroes 2 Asteroids Hyper 64 Automobili Lamborghini Banjo-Kazooie Banjo-Tooie Bassmasters 2000 Batman Beyond : Return of the Joker BattleTanx BattleTanx - Global Assault Battlezone : Rise of the Black Dogs Beetle Adventure Racing! Big Mountain 2000 Bio F.R.E.A.K.S. Blast Corps Blues Brothers 2000 Body Harvest Bomberman 64 Bomberman 64 : The Second Attack! Bomberman Hero Bottom of the 9th Brunswick Circuit Pro Bowling Buck Bumble Bust-A-Move '99 Bust-A-Move 2: Arcade Edition California Speed Carmageddon 64 Castlevania Castlevania : Legacy of Darkness Chameleon Twist Chameleon Twist 2 Charlie Blast's Territory Chopper Attack Clay Fighter : Sculptor's Cut Clay Fighter 63 1-3 Command & Conquer Conker's Bad Fur Day Cruis'n Exotica Cruis'n USA Cruis'n World CyberTiger Daikatana Dark Rift Deadly Arts Destruction Derby 64 Diddy Kong Racing Donald Duck : Goin' Qu@ckers*! Donkey Kong 64 Doom 64 Dr. Mario 64 Dual Heroes Duck Dodgers Starring Daffy Duck Duke Nukem : Zero Hour Duke Nukem 64 Earthworm Jim 3D ECW Hardcore Revolution Elmo's Letter Adventure Elmo's Number Journey Excitebike 64 Extreme-G Extreme-G 2 F-1 World Grand Prix F-Zero X F1 Pole Position 64 FIFA 99 FIFA Soccer 64 FIFA: Road to World Cup 98 Fighter Destiny 2 Fighters -

Arcade-Style Game Design: Postwar Pinball and The

ARCADE-STYLE GAME DESIGN: POSTWAR PINBALL AND THE GOLDEN AGE OF COIN-OP VIDEOGAMES A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty by Christopher Lee DeLeon In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Digital Media in the School of Literature, Communication and Culture Georgia Institute of Technology May 2012 ARCADE-STYLE GAME DESIGN: POSTWAR PINBALL AND THE GOLDEN AGE OF COIN-OP VIDEOGAMES Approved by: Dr. Ian Bogost, Advisor Dr. John Sharp School of LCC School of LCC Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Brian Magerko Steve Swink School of LCC Creative Director Georgia Institute of Technology Enemy Airship Dr. Celia Pearce School of LCC Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: March 27, 2012 In memory of Eric Gary Frazer, 1984–2001. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank: Danyell Brookbank, for companionship and patience in our transition to Atlanta. Ian Bogost, John Sharp, Brian Magerko, Celia Pearce, and Steve Swink for ongoing advice, feedback, and support as members of my thesis committee. Andrew Quitmeyer, for immediately encouraging my budding pinball obsession. Michael Nitsche and Patrick Coursey, for also getting high scores on Arnie. Steve Riesenberger, Michael Licht, and Tim Ford for encouragement at EALA. Curt Bererton, Mathilde Pignol, Dave Hershberger, and Josh Wagner for support and patience at ZipZapPlay. John Nesky, for his assistance, talent, and inspiration over the years. Lou Fasulo, for his encouragement and friendship at Sonic Boom and Z2Live. Michael Lewis, Harmon Pollock, and Tina Ziemek for help at Stupid Fun Club. Steven L. Kent, for writing the pinball chapter in his book that inspired this thesis. -

Stubbs the Zombie: Rebel Without 21 Starship Troopers PC Continues to Set the Standard for Both Technology and Advancements in Gameplay

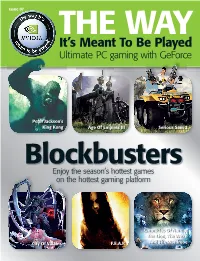

Issue 07 THE WAY It’s Meant To Be Played Peter Jackson’s King Kong Age Of Empires III Serious Sam 2 Blockbusters Enjoy the season’s hottest games on the hottest gaming platform Chronicles Of Narnia: The Lion, The Witch City Of Villains F.E.A.R And The Wardrobe NNVM07.p01usVM07.p01us 1 119/9/059/9/05 33:57:57:57:57 ppmm The way it’s meant to be played 3 6 7 8 Welcome Welcome to Issue 7 of The Way It’s Meant 12 13 to be Played, the magazine that showcases the very best of the latest PC games. All the 30 titles featured in this issue are participants in NVIDIA’s The Way It’s Meant To Be Played program, a campaign designed to deliver the best interactive entertainment experience. Development teams taking part in 14 19 the program are given access to NVIDIA’s hardware, with NVIDIA’s developer technology engineers on hand to help them get the very best graphics and effects into their new games. The games are then rigorously tested by NVIDIA for compatibility, stability and reliability to ensure that customers can buy any game with the TWIMTBP logo on the box and feel confident that the game will deliver the ultimate install- and-play experience when played with an Contents NVIDIA GeForce-based graphics card. Game developers today like to use 3 NVIDIA news 14 Chronicles Of Narnia: The Lion, Shader Model 3.0 technology for stunning, The Witch And The Wardrobe complex cinematic effects – a technology TWIMTBP games 15 Peter Jackson’s King Kong fully supported by all the latest NVIDIA 4 Vietcong 2 16 F.E.A.R. -

Deathsport Science Fiction Double Feature

KOSMORAMANIGHT Deathsport Science Fiction Double Feature: Efterårssæsonens første Kosmorama Night starter på højeste oktantal med to af 70’emes mest bizarre spekulationsfilm, Death Race 2000 &£ Rollerball (begge 1975), der hver især har kigget i krystal kuglen for at se på fremti dens ultravoldelige fritids- forlystelser I det lyse solarium ligger den halvdøde Moonpie - hans ven, James Caan, forsøger at kommunikere med sin beindstløse kamp- kollega. Death Race 2000 campede film, der har alt: action, men tværtimod søger at lære os at Excentrikeren Paul B artel har in- blod, nøgne kvinder, biljagter, mon tage afstand fra samme. Hvorvidt XZfstrueret denne grovkornede sat stre, masser af billige grin og tilpas det lykkedes må være op til den en ire, der foregår i et fascistisk USA i med forsonende social-satirisk gar kelte. Politiken mente i sin tid, at en ikke alt for fjern fremtid. Fem niture til at få det mere intellektu filmen faktisk formåede at fremvise personer deltager i et væddeløb elle publikum på krogen. volden uden at gøre den underhol tværs over USA, hvor de indtJener dende. Den begeJstrede anmelder points alt efter hvor mange forbi Henrik M. Jakobsen konkluderede, passerende de kan påkøre og dræbe Rollerball at ‘man gik fra denne fascinerende på deres veJ [børn giver ekstra po Death Race 2000 var i modsætning og frastødende fremtidsvision med int, så devisen lyder: ‘if they scatter, til Rollerball leveringsdygtig i et vist kvalme og indre kvæstelser’. Infor go for the baby!). Filmen er baseret mål af selvironi, og kostede kun en mations Morten Piil fandt derimod, på en historie af vor egen Ib Mel brøkdel af de enorme summer Uni at filmen var et af de modbydeligste chior, og i de bærende roller ses ted Artists ofrede på den ucharme og mest prætentiøse makværker bl.a. -

Movie in Search of America: the Rhetoric of Myth in Easy Rider

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2005 Movie in search of America: The rhetoric of myth in Easy Rider Hayley Susan Raynes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the American Film Studies Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Raynes, Hayley Susan, "Movie in search of America: The rhetoric of myth in Easy Rider" (2005). Theses Digitization Project. 2804. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2804 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MOVIE IN SEARCH OF AMERICA: THE RHETORIC OF MYTH IN EASY RIDER A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Hayley Susan Raynes March 2005 MOVIE IN SEARCH OF AMERICA: THE RHETORIC OF MYTH IN EASY RIDER A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino' by Hayley Susan Raynes March 2005 © 2005 Hayley Susan Raynes ABSTRACT Chronicling the cross-country journey of two hippies on motorcycles, Easy Rider is an historical fiction embodying the ideals, naivete, politics and hypocrisies of 1960's America. This thesis is a rhetorical analysis of Easy Rider exploring how auteurs Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper and Terry Southern's use of road, regional and cowboy mythology creates a text that simultaneously exposes and is dominated by the ironies inherent in American culture while breathing new life into the cowboy myth and reaffirming his place as one of America's most enduring cultural icons.