Alpha-Taxonomy in the Cricetid Rodent Neomicroxus, a First Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chocó-Darién Conservation Corridor

July 4, 2011 The Chocó-Darién Conservation Corridor A Project Design Note for Validation to Climate, Community, and Biodiversity (CCB) Standards (2nd Edition). CCB Project Design Document – July 4, 2011 Executive Summary Colombia is home to over 10% of the world’s plant and animal species despite covering just 0.7% of the planet’s surface, and has more registered species of birds and amphibians than any other country in the world. Along Colombia’s northwest border with Panama lies the Darién region, one of the most diverse ecosystems of the American tropics, a recognized biodiversity hotspot, and home to two UNESCO Natural World Heritage sites. The spectacular rainforests of the Darien shelter populations of endangered species such as the jaguar, spider monkey, wild dog, and peregrine falcon, as well as numerous rare species that exist nowhere else on the planet. The Darién is also home to a diverse group of Afro-Colombian, indigenous, and mestizo communities who depend on these natural resources. On August 1, 2005, the Council of Afro-Colombian Communities of the Tolo River Basin (COCOMASUR) was awarded collective land title to over 13,465 hectares of rainforest in the Serranía del Darién in the municipality of Acandí, Chocó in recognition of their traditional lifestyles and longstanding presence in the region. If they are to preserve the forests and their traditional way of life, these communities must overcome considerable challenges. During 2001- 2010 alone, over 10% of the natural forest cover of the surrounding region was converted to pasture for cattle ranching or cleared to support unsustainable agricultural practices. -

Advances in Cytogenetics of Brazilian Rodents: Cytotaxonomy, Chromosome Evolution and New Karyotypic Data

COMPARATIVE A peer-reviewed open-access journal CompCytogenAdvances 11(4): 833–892 in cytogenetics (2017) of Brazilian rodents: cytotaxonomy, chromosome evolution... 833 doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v11i4.19925 RESEARCH ARTICLE Cytogenetics http://compcytogen.pensoft.net International Journal of Plant & Animal Cytogenetics, Karyosystematics, and Molecular Systematics Advances in cytogenetics of Brazilian rodents: cytotaxonomy, chromosome evolution and new karyotypic data Camilla Bruno Di-Nizo1, Karina Rodrigues da Silva Banci1, Yukie Sato-Kuwabara2, Maria José de J. Silva1 1 Laboratório de Ecologia e Evolução, Instituto Butantan, Avenida Vital Brazil, 1500, CEP 05503-900, São Paulo, SP, Brazil 2 Departamento de Genética e Biologia Evolutiva, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo, Rua do Matão 277, CEP 05508-900, São Paulo, SP, Brazil Corresponding author: Maria José de J. Silva ([email protected]) Academic editor: A. Barabanov | Received 1 August 2017 | Accepted 23 October 2017 | Published 21 December 2017 http://zoobank.org/203690A5-3F53-4C78-A64F-C2EB2A34A67C Citation: Di-Nizo CB, Banci KRS, Sato-Kuwabara Y, Silva MJJ (2017) Advances in cytogenetics of Brazilian rodents: cytotaxonomy, chromosome evolution and new karyotypic data. Comparative Cytogenetics 11(4): 833–892. https://doi. org/10.3897/CompCytogen.v11i4.19925 Abstract Rodents constitute one of the most diversified mammalian orders. Due to the morphological similarity in many of the groups, their taxonomy is controversial. Karyotype information proved to be an important tool for distinguishing some species because some of them are species-specific. Additionally, rodents can be an excellent model for chromosome evolution studies since many rearrangements have been described in this group.This work brings a review of cytogenetic data of Brazilian rodents, with information about diploid and fundamental numbers, polymorphisms, and geographical distribution. -

Rodentia: Cricetidae: Sigmodontinae) in São Paulo State, Southeastern Brazil: a Locally Extinct Species?

Volume 55(4):69‑80, 2015 THE PRESENCE OF WILFREDOMYS OENAX (RODENTIA: CRICETIDAE: SIGMODONTINAE) IN SÃO PAULO STATE, SOUTHEASTERN BRAZIL: A LOCALLY EXTINCT SPECIES? MARCUS VINÍCIUS BRANDÃO¹ ABSTRACT The Rufous-nosed Mouse Wilfredomys oenax is a rare Sigmodontinae rodent known from scarce records from northern Uruguay and south and southeastern Brazil. This species is under- represented in scientific collections and is currently classified as threathened, being considered extinct at Curitiba, Paraná, the only confirmed locality of the species at southeastern Brazil. Although specimens from São Paulo were already reported, the presence of this species in this state seems to have passed unnoticed in recent literature. Through detailed morphological ana- lyzes of specimens cited in literature, the present work confirms and discusses the presence of this species in São Paulo state from a specimen collected more than 70 years ago. Recently, by the use of modern sampling methods, other rare Sigmodontinae rodents, such as Abrawayomys ruschii, Phaenomys ferrugineous and Rhagomys rufescens, have been recorded to São Paulo state. However, no specimen of Wilfredomys oenax has been recently reported indicating that this species might be locally extinct. The record mentioned here adds another species to the state of São Paulo mammal diversity and reinforces the urgency of studying Wilfredomys oenax. Key-Words: Atlantic Forest; Scientific collection; Threatened species. INTRODUCTION São Paulo is one the most studied states in Brazil regarding to fauna. Mammal lists from this state have Mammal species lists based on voucher-speci- been elaborated since the late XIX century (Von Iher- mens and literature records are essential for offering ing, 1894; Vieira, 1944a, b, 1946, 1950, 1953; Vivo, groundwork to understand a species distribution and 1998). -

Supporting Files

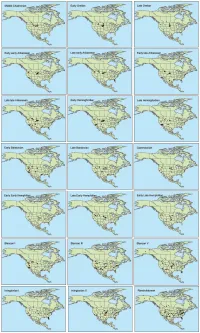

Table S1. Summary of Special Emissions Report Scenarios (SERs) to which we fit climate models for extant mammalian species. Mean Annual Temperature Standard Scenario year (˚C) Deviation Standard Error Present 4.447 15.850 0.057 B1_low 2050s 5.941 15.540 0.056 B1 2050s 6.926 15.420 0.056 A1b 2050s 7.602 15.336 0.056 A2 2050s 8.674 15.163 0.055 A1b 2080s 7.390 15.444 0.056 A2 2080s 9.196 15.198 0.055 A2_top 2080s 11.225 14.721 0.053 Table S2. List of mammalian taxa included and excluded from the species distribution models. -

The Neotropical Region Sensu the Areas of Endemism of Terrestrial Mammals

Australian Systematic Botany, 2017, 30, 470–484 ©CSIRO 2017 doi:10.1071/SB16053_AC Supplementary material The Neotropical region sensu the areas of endemism of terrestrial mammals Elkin Alexi Noguera-UrbanoA,B,C,D and Tania EscalanteB APosgrado en Ciencias Biológicas, Unidad de Posgrado, Edificio A primer piso, Circuito de Posgrados, Ciudad Universitaria, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), 04510 Mexico City, Mexico. BGrupo de Investigación en Biogeografía de la Conservación, Departamento de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), 04510 Mexico City, Mexico. CGrupo de Investigación de Ecología Evolutiva, Departamento de Biología, Universidad de Nariño, Ciudadela Universitaria Torobajo, 1175-1176 Nariño, Colombia. DCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Page 1 of 18 Australian Systematic Botany, 2017, 30, 470–484 ©CSIRO 2017 doi:10.1071/SB16053_AC Table S1. List of taxa processed Number Taxon Number Taxon 1 Abrawayaomys ruschii 55 Akodon montensis 2 Abrocoma 56 Akodon mystax 3 Abrocoma bennettii 57 Akodon neocenus 4 Abrocoma boliviensis 58 Akodon oenos 5 Abrocoma budini 59 Akodon orophilus 6 Abrocoma cinerea 60 Akodon paranaensis 7 Abrocoma famatina 61 Akodon pervalens 8 Abrocoma shistacea 62 Akodon philipmyersi 9 Abrocoma uspallata 63 Akodon reigi 10 Abrocoma vaccarum 64 Akodon sanctipaulensis 11 Abrocomidae 65 Akodon serrensis 12 Abrothrix 66 Akodon siberiae 13 Abrothrix andinus 67 Akodon simulator 14 Abrothrix hershkovitzi 68 Akodon spegazzinii 15 Abrothrix illuteus -

With Focus on the Genus Handleyomys and Related Taxa

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2015-04-01 Evolution and Biogeography of Mesoamerican Small Mammals: With Focus on the Genus Handleyomys and Related Taxa Ana Villalba Almendra Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Villalba Almendra, Ana, "Evolution and Biogeography of Mesoamerican Small Mammals: With Focus on the Genus Handleyomys and Related Taxa" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 5812. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5812 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Evolution and Biogeography of Mesoamerican Small Mammals: Focus on the Genus Handleyomys and Related Taxa Ana Laura Villalba Almendra A dissertation submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Duke S. Rogers, Chair Byron J. Adams Jerald B. Johnson Leigh A. Johnson Eric A. Rickart Department of Biology Brigham Young University March 2015 Copyright © 2015 Ana Laura Villalba Almendra All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Evolution and Biogeography of Mesoamerican Small Mammals: Focus on the Genus Handleyomys and Related Taxa Ana Laura Villalba Almendra Department of Biology, BYU Doctor of Philosophy Mesoamerica is considered a biodiversity hot spot with levels of endemism and species diversity likely underestimated. For mammals, the patterns of diversification of Mesoamerican taxa still are controversial. Reasons for this include the region’s complex geologic history, and the relatively recent timing of such geological events. -

Parasitizing Akodon Montensis (Rodentia: Cricetidae) in the Southern Region of Brazil Revista Brasileira De Parasitologia Veterinária, Vol

Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária ISSN: 0103-846X [email protected] Colégio Brasileiro de Parasitologia Veterinária Brasil Trevisan Gressler, Lucas; da Silva Krawczak, Felipe; Knoff, Marcelo; Gonzalez Monteiro, Silvia; Bahia Labruna, Marcelo; de Campos Binder, Lina; Sobotyk de Oliveira, Caroline; Notarnicola, Juliana Litomosoides silvai (Nematoda: Onchocercidae) parasitizing Akodon montensis (Rodentia: Cricetidae) in the southern region of Brazil Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária, vol. 26, núm. 4, octubre, 2017, pp. 433- 438 Colégio Brasileiro de Parasitologia Veterinária Jaboticabal, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=397853594005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Original Article Braz. J. Vet. Parasitol., Jaboticabal, v. 26, n. 4, p. 433-438, oct.-dec. 2017 ISSN 0103-846X (Print) / ISSN 1984-2961 (Electronic) Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612017060 Litomosoides silvai (Nematoda: Onchocercidae) parasitizing Akodon montensis (Rodentia: Cricetidae) in the southern region of Brazil Litomosoides silvai (Nematoda: Onchocercidae) parasitando Akodon montensis (Rodentia: Cricetidae) na região Sul do Brasil Lucas Trevisan Gressler1; Felipe da Silva Krawczak2,3; Marcelo Knoff4; Silvia Gonzalez Monteiro1*; Marcelo Bahia Labruna2; -

Check List 4(2): 174–177, 2008

Check List 4(2): 174–177, 2008. ISSN: 1809-127X LISTS OF SPECIES Rodents (Rodentia) and marsupials (Didelphimorphia) in the municipalities of Ilhéus and Pau Brasil, state of Bahia, Brazil. Lena Geise 1 Luciana Guedes Pereira 2 1 Laboratório de Mastozoologia, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Rua São Francisco Xavier 524, CEP 220559-900, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Laboratório de Biologia e Parasitologia de Mamíferos Silvestres Reservatórios, Departamento de Medicina Tropical, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz. CEP 21045-900, Avenida Brasil 4365, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. Abstract: The present study provides a list of small mammals from the coastal south part of the state of Bahia. Live- traps were settled in Atlantic Forest fragments where cacao (Theobroma cacao) plantations are widespread. During a short-term inventory performed in February 2003, 13 specimens from eight species of small mammals were collected. Introduction In all habitats from the Atlantic Forest, marsupials Fragments with cacao are still common along the and rodents comprise the most diverse group of coastal area of Bahia, in which important mammal mammals. Knowledge about distribution patterns diversity can be observed. There we can find of those mammals is increasing with long-term some endemic species, as Leontopithecus inventories and some sporadic studies with limited chrysomelas, Bradypus torquatus, Trinomys trapping effort. Another tool that increases the mirapitanga, Phyllomys unicolor, Callistomys knowledge about small mammals, particularly in pictus, and Cebus xanthosternos. Emamdie and the case of sigmodontine rodents, is the correct Warren (1993) noted that arboreal rodents, as the species identification using genetic techniques, Neotropical red-squirrel (Sciurus granatensis), are especially karyotypes (Geise et al. -

DNA Barcoding of Sigmodontine Rodents: Identifying Wildlife Reservoirs of Zoonoses

DNA Barcoding of Sigmodontine Rodents: Identifying Wildlife Reservoirs of Zoonoses Lívia Müller1,2, Gislene L. Gonçalves1,2, Pedro Cordeiro-Estrela1,2,3,4*, Jorge R. Marinho5, Sérgio L. Althoff6, André. F. Testoni6, Enrique M. González7, Thales R. O. Freitas1,2 1 Laboratório de Citogenética e Evolução, Departamento de Genética, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 2 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Genética e Biologia Molecular, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 3 Laboratório de Biologia e Parasitologia de Mamíferos Silvestres Reservatórios, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz. Pavilhão Lauro Travassos, Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 4 Laboratório de Mamíferos, Departamento de Sistemática e Ecologia, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, Paraíba, Brazil, 5 Universidade Regional Integrada do Alto Uruguai e das Missões, Erechim, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 6 Fundação Universidade Regional de Blumenau, Blumenau, Santa Catarina, Brazil, 7 Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Montevideo, Uruguay Abstract Species identification through DNA barcoding is a tool to be added to taxonomic procedures, once it has been validated. Applying barcoding techniques in public health would aid in the identification and correct delimitation of the distribution of rodents from the subfamily Sigmodontinae. These rodents are reservoirs of etiological agents of zoonoses including arenaviruses, hantaviruses, Chagas disease and leishmaniasis. In this study we compared distance-based and probabilistic phylogenetic inference methods to evaluate the performance of cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) in sigmodontine identification. A total of 130 sequences from 21 field-trapped species (13 genera), mainly from southern Brazil, were generated and analyzed, together with 58 GenBank sequences (24 species; 10 genera). -

MAMÍFEROS Diversidad Endémica Requiere De Muchos Años De Autor: Mario Escobedo Torres Estudio

.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................no. 27 ....................................................................................................................... 27 Perú: Tapiche-Blanco Perú:Tapiche-Blanco Instituciones participantes/ Participating Institutions The Field Museum Centro para el Desarrollo del Indígena Amazónico (CEDIA) Instituto de Investigaciones de la Amazonía Peruana (IIAP) Servicio Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas por el Estado (SERNANP) Servicio Nacional Forestal y de Fauna Silvestre (SERFOR) Herbario Amazonense de la Universidad Nacional de la Amazonía Peruana (AMAZ) Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos Centro de Ornitología y Biodiversidad (CORBIDI) -

Redalyc.ESTRUCTURA DE LA DIETA DE ROEDORES

Mastozoología Neotropical ISSN: 0327-9383 [email protected] Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Argentina Polop, Francisco; Sepúlveda, Lorena; Pelliza Sbriller, Alicia; Polop, Jaime; Provensal, M. Cecilia ESTRUCTURA DE LA DIETA DE ROEDORES SIGMODONTINOS EN ARBUSTALES DEL ECOTONO BOSQUE-ESTEPA DEL SUROESTE DE ARGENTINA Mastozoología Neotropical, vol. 22, núm. 1, 2015, pp. 85-95 Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Tucumán, Argentina Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45739766009 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Mastozoología Neotropical, 22(1):85-95, Mendoza, 2015 Copyright ©SAREM, 2015 Versión impresa ISSN 0327-9383 http://www.sarem.org.ar Versión on-line ISSN 1666-0536 Artículo ESTRUCTURA DE LA DIETA DE ROEDORES SIGMODONTINOS EN ARBUSTALES DEL ECOTONO BOSQUE-ESTEPA DEL SUROESTE DE ARGENTINA Francisco Polop1, Lorena Sepúlveda2, Alicia Pelliza Sbriller2, Jaime Polop1 y M. Cecilia Provensal1 1 Departamento de Ciencias Naturales, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Físico-Químicas y Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Río Cuarto, Agencia Postal Nº 3, 5800 Río Cuarto, Córdoba, Argentina. [Correspondencia: M. Cecilia Provensal <[email protected]>]. 2 Laboratorio Microhistología, Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria. Estación Experimental Agropecuaria de Bariloche. S. C. de Bariloche. Río Negro. Argentina. RESUMEN. El objetivo de este estudio es conocer la dieta de especies de roedores que coexisten en arbustales del ecotono bosque-estepa de la Patagonia Argentina. -

Comunidade De Pequenos Mamíferos No Parque Estadual Do Ibitipoca

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE JUIZ DE FORA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ECOLOGIA Michel Carneiro Delgado COMUNIDADE DE PEQUENOS MAMÍFEROS NO PARQUE ESTADUAL DO IBITIPOCA Juiz de Fora, abril de 2017 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE JUIZ DE FORA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ECOLOGIA Michel Carneiro Delgado COMUNIDADE DE PEQUENOS MAMÍFEROS NO PARQUE ESTADUAL DO IBITIPOCA Dissertação apresentada ao Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, da Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do Título de Mestre em Ecologia Aplicada ao Manejo e Conservação e Manejo de Recursos Naturais. Orientador: Dr. Pedro Henrique Nobre Co-orientadora: Dra. Gisele Mendes Lessa del Giúdice Juiz de Fora, abril de 2017 1 2 3 RESUMO GERAL Embora muitos autores considerem que a riqueza de espécies é maior na floresta tropical de planície, estudos mais recentes têm mostrado que a riqueza de espécies alcança seu valor máximo em altitudes medianas. Em um mosaico de habitats é possível tentar entender como as espécies selecionam e utilizam os ambientes decorrentes da disponibilidade de recursos. Conhecer bem a distribuição dos espécimes nestes microhabitats e os mecanismos que controlam a distribuição das espécies em áreas preservadas é fundamental para servir de suporte a propostas de manejo e conservação. Uma vez caracterizadas diferentes fitofisionomias no PEIB, consideramos cada uma dessas formações como habitats específicos e testamos se a comunidade de pequenos mamíferos não voadores residente foi diferente entre quatro fitofisionomias. As ordens Rodentia, Chiroptera e Didelphimorpha são críticas quanto ao conhecimento taxonômico. O capítulo I traz a lista de espécies de pequenos mamíferos não voadores encontrada no PEIB, discutida em relação à literatura atual.