Experimental Reality: Principles for the Design of Augmented Environments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

THE NAMES LIST Version 7.2 -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

List of Names, Vers. 7.2 THE NAMES LIST Version 7.2 We apologize if any names are misspelled, misplaced or in any other way misused – we can’t know everything! Shorter versions and/or nicknames are listed as Name (Short version) Some names are listed with their meaning in English as Name=english word All firstnames marked with an * are rather old-fashioned and not common among younger people any more. The surnames marked with an ** are names of prominent persons which are actually very rare. CONTEMPORARY NAMES (Bear in mind that several countries, China to name one, list surnames/family names before firstnames/personal names!) Song Abdullah African Surnames Songo’O Achmed Tchami Ahmet Adepoju Tchango Akif Amokachi Tchoutang Ali Amunike Tinkler Arif Andem Tovey Aykut Angibeaud Bahri Ardense Bekir Babayaro Arabian Female Firstnames Bülent Baruwa Aynur Durmus Billong Ayse Dursun Dosu Aysel Erdal Ekoku Belkis Erkan Etamé Berna Erol Finidi Cigdem Fahri Foe Damla Gazi Ikpeba Demet Halifi Ipoua Derya Halil Issa Dilek Hamza Kalla Elif Hassan Kanu Elo Hüsein Khumaleo Fahrie Iskender Kipketer Fatima Ismail Lobé Fatma Ismet M’butu Fehime Khalib Mapela Gulizar Khaled Masinga Gülcan Leyla Mboma Hacer Mehmet Mimboe Hatice Yusuf Moeti Hazel Zeki Moshoeu Hediye Ziya Motaung Hüeyla Moukoko Makbule Obafemi Medine Arabian Surnames Ohenen Mürüret Al - Okechukwu Nazli Okocha Shahrzad Abedzadeh Okpara Tanzu Al Awad Olembé Al Daeya Oliseh Arabian Male Firstnames Al Dokhy Opakuru Al Dossari Abdul Redebe Al Dossary Compiled By Krikkit Gamblers Page 1 List of Names, -

Convocation Collation Des Grades 2021 Spring / Printemps

CONVOCATION COLLATION DES GRADES 2021 SPRING / PRINTEMPS SCIENCE / SCIENCES VIRTUAL CEREMONY / CÉRÉMONIE VIRTUELLE I JUNE 11 / 11 JUIN 2021 1 PM / 13 00 H CONVOCATION OF: COLLATION DES GRADES DE : 2021 II FACULTY OF SCIENCE FACULTÉ DES SCIENCES Bieler School of Environment École de l’environnement Bieler School of Computer Science École d’informatique 01 PRINCIPAL'S MESSAGE MESSAGE DE LA PRINCIPALE ongratulations to our newest alumni! élicitations à nos nouveaux diplômés! CI know you were looking forward to walking FJe sais que vous aviez hâte de monter sur across the Convocation stage and I am sorry scène pour recevoir votre diplôme, et je suis that the current situation regarding COVID-19 désolée qu’en raison de la pandémie, nous ne does not make it possible to hold Convocation puissions pas tenir les cérémonies de collation in person. I am pleased, however, that we will des grades en personne. Toutefois, je suis ravie be able to come together, virtually, to celebrate que nous puissions nous réunir virtuellement your achievements and success. Today, as we pour célébrer vos réalisations et votre réussite. celebrate our Bicentennial, we welcome you to Aujourd’hui, alors que nous célébrons le a network of more than 275,000 people across Bicentenaire de l’Université, nous vous more than 180 countries connected through accueillons dans un réseau de plus de 275 000 their alma mater. McGill’s alumni are committed membres répartis dans au-delà de 180 pays, to turning their knowledge, skills, and passions tous unis par une même alma mater. Les into making the world a better place. -

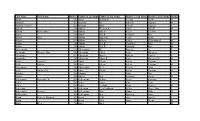

Last Name First Name Birth Yrfather's Last Name Father's

Last Name First Name Birth YrFather's Last Name Father's First Name Mother's Last Name Mother's First Name Gender Aaron 1907 Aaron Benjaman Shields Minnie M Aaslund 1893 Aaslund Ole Johnson Augusta M Aaslund (Twins) 1895 Aaslund Oluf Carlson Augusta F Abbeal 1906 Abbeal William A Conlee Nina E M Abbitz Bertha Dora 1896 Abbitz Albert Keller Caroline F Abbot 1905 Abbot Earl R Seldorff Rose F Abbott Zella 1891 Abbott James H Perry Lissie F Abbott 1896 Abbott Marion Forder Charolotta M M Abbott 1904 Abbott Earl R Van Horn Rose M Abbott 1906 Abbott Earl R Silsdorff Rose M Abercrombie 1899 Abercrombie W Rogers A F Abernathy Marjorie May 1907 Abernathy Elmer Scott Margaret F Abernathy 1892 Abernathy Wm A Roberts Laura J F Abernethy 1905 Abernethy Elmer R Scott Margaret M M Abikz Louisa E 1902 Abikz Albert Keller Caroline F Abilz Charles 1903 Abilz Albert Keller Caroline M Abircombie 1901 Abircombie W A Racher Allos F Abitz Arthur Carl 1899 Abitz Albert Keller Caroline M Abrams 1902 Abrams L E Baker May F Absher 1905 Absher Ben Spillman Zoida M Achermann Bernadine W 1904 Ackermann Arthur Krone Karolina F Acker 1903 Acker Louis Carr Lena F Acker 1907 Acker Leyland Ryan Beatrice M Ackerman 1904 Ackerman Cecil Addison Willis Bessie May F Ackermann Berwyn 1905 Ackermann Max Mann Dolly M Acklengton 1892 Achlengton A A Riacting Nattie F Acton Rebecca Elizabeth 1891 Acton T M Cox Josie E F Acton 1900 Acton Chas Payne Minnie M Adair Elles 1906 Adair Adel M Last Name First Name Birth YrFather's Last Name Father's First Name Mother's Last Name Mother's -

Histoire Et Glossaire Du Normand De L'anglais Et De La Langue Francaise D

v 5 ^tisjaci* .<2^r3î *t*~ HISTOIRE ET GLOSSAIRE DU NORMAND DÉ L'ANGLAIS ET DE LA LANGUE FRANÇAISE AVRÀNCUES. IMPRIMERIE DE H. HAMBIS. HISTOIRE GLOSSAIRE DU NORMAND DE L'ANGLAIS ET DE LA LANGUE FRANÇAISE D'APRÈS LA MÉTHODE Historique, Naturelle et Étymologique DÉVELOPPEMENT D'UN MÉMOIRE COCHONNÉ PAR L'ACADÉMIE DE ROIEN EDOUARD LE HÉRICHER lisent Je Rhétoiique au Collège d'Avranches , Correspondait du Ministre de l'Instruction publique TOME TROISIEME PARIS AVRANCHES Chez AUBRY , Rue Dauphine 10. Constitlitiok j Chez ANIT.AY, Rue de la — 5t).j — N NANÉES, du 1. nanus, en gr. vocvoç, d'où le fr. Nain, Naine, prob. Nabot, le v. f. nane, le n. naw-ne, naine, nabotte, femme de petite taille, :napi.n (Orne), petit garçon, d'ailleurs knapit, id., en isl.; napet (Av.), nain. NAPÉES, du 1. napus, d'où le fr. Navet, Navette, l'a. pop. sweet navew, navet (Family herbal, 244), le n. iu- viad, navet, natccbe, s. f. péj., le raphanus raphanislrum, navets, en v. f. nabine s. f . plantation de un navière, , ; dit iuveau dans le Bessin : « Porreaux. chelets (choux) ei naveaux; o (Tarif de Bay.) navet-dc-diable. la bryone; en v. f. navel, navet, du 1. napellus, d'où le nom de l'Aconil- napel. NARRÉES, du 1. narrare, d'où le fr. Narrer, Narra- teur, Narration, Narratif, Inénarrable, l'a. narrate, narra- tion, narrable, narrative, narrator; le n. naber, attendre longtemps, cilé par MM. du Méril (Diet, dupât, n.), n'a qu'un raport de forme avec cette famille; ils l'expliquent par l'isl. -

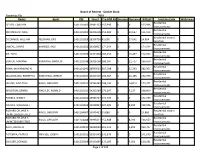

Board of Review

Board of Review - Docket Book Township: Ela 2019 Owner Agent PIN Case # Pre-BOR AV Increase Decrease BOR AV Land Use Code Withdrawn Residential GELLER, CAROLYN 1401101002 19981322 155,996 0 0 155,996 Improvements Residential ANTONIJEVIC, MIKE 1401101003 19206606 152,281 0 20,627 131,654 Improvements Residential Vacant O CONNOR, WILLIAM FELDMAN, ERIC 1401101029 19208730 42,606 0 17,642 24,964 land/lots Residential LANCAU, MARIE KAMEGO, KYLE 1401101032 19206827 174,544 0 0 174,544 Improvements Residential XIE, YINYI 1401101036 19201804 185,456 0 10,457 174,999 Improvements Residential SHAYUK, MARYNA RUKAVINA, ANDREW 1401101038 19206268 189,387 0 22,737 166,650 Improvements Residential KHAN, MUHAMMAD N 1401101042 19993635 307,598 0 25,293 282,305 Improvements Residential MALDONADO, ROBERTO J ROSENFELD, JEREMY 1401102004 19207225 160,984 0 10,185 150,799 Improvements Residential HUANG, XIAO TIAN RIGGS, GREGORY 1401102011 19986349 188,190 0 14,819 173,371 Improvements Residential WALDRON, DENNIS KINGSLEY, RONALD 1401102013 19202289 176,097 0 7,237 168,860 Improvements Residential PODREZ, SERGEY 1401102022 19986727 154,749 0 0 154,749 Improvements Residential CIACCIO, NICHOLAS J 1401102025 19998824 207,585 0 8,599 198,986 Improvements RICHARD OR JANE A Residential Vacant RIGGS, GREGORY 1401104007 19995421 15,886 0 0 15,886 LAFNITZEGGER TTEES land/lots RICHARD OR JANE A Residential RIGGS, GREGORY 1401104008 19995421 154,948 0 8,296 146,652 LAFNITZEGGER TTEES Improvements Residential RATH, DANIEL D 1401104010 19990094 203,116 0 3,409 199,707 -

Family Lines from Companions of the Conqueror

Companions of the Conqueror and the Conqueror 1 Those Companions of William the Conqueror From Whom Ralph Edward Griswold and Madge Elaine Turner Are Descended and Their Descents from The Conqueror Himself 18 May 2002 Note: This is a working document. The lines were copied quickly out of the Griswold-Turner data base and have not yet been retraced. They have cer- tainly not been proved by the accepted sources. This is a massive project that is done in pieces, and when one piece is done it is necessary to put it aside for a while before gaining the energy and enthusiasm to continue. It will be a working document for some time to come. This document also does not contain all the descents through the Turner or Newton Lines 2 Many men (women are not mentioned) accompanied William the Conqueror on his invasion of England. Many men and women have claimed to be descended from one or more of the= Only a few of these persons are documented; they were the leaders and colleagues of William of Normandy who were of sufficient note to have been recorded. Various sources for the names of “companions” (those who were immediate associates and were rewarded with land and responsibility in England) exist. Not all of them have been consulted for this document. New material is in preparation by reputable scholars that will aid researchers in this task. For the present we have used a list from J. R. Planché. The Conqueror and His Companions. Somerset Herald. London: Tinsley Brothers, 1874.. The persons listed here are not the complete list but constitute a subset from which either Ralph Edward Griswold or Madge Elaine Turner (or both) are descended). -

2017 Annual Report Change in Net Assets (303,552) Classic Car Services Davenport Trust Fund St

365 DAYS OF GIVING HELP & HOPE CATHOLIC CHARITIES MAINE ANNUAL REPORT 2017 “When we give cheerfully Our Mission: and receive gratefully, To empower and everyone is blessed.” strengthen individuals — MAYA ANGELOU and families of all faiths, by providing innovative, community-based social services throughout Maine. Here’s to those who gave to Catholic Charities Maine in 2017 — to those who shared their resources to keep our programs and services operating, and to those who gave of themselves, with their time, their treasures, and their talents. We cannot fulfill our mission without you — your capacity to care, to respond with compassion, and give of yourselves unconditionally. Thanks to your support, working through our communities and parishes, we can continue to serve the poor, protect the vulnerable, and welcome the stranger. In this annual report we celebrate the impact of your good works, and spotlight some of the creative, thoughtful ways our volunteers and donors were able to give: — a parish refitting bicycles for newly-arrived refugees to give them freedom and independence — a therapist donating dolls to give seniors companionship and love — a volunteer sharing a love of reading to give kids a brighter start in life — corporate sponsors improving their communities with gifts of money and volunteers We recognize with gratitude the many donors who have invested in Catholic Charities Maine. Your generosity inspires us. Ring! Ring! A great idea Donations of adult helmets, locks, or lights, as well as gently used bikes, GIVES are welcome! neighbors a lift At All Saints Parish, a group of seven Roman Catholic churches in midcoast Maine, they have a motto: “We believe and we share.” So when Catholic Charities put out the word that it was seeking donations of gently used bicycles for our Refugee and Immigration Services (RIS) program, All Saints promptly answered the bell. -

MUSIC in SOCIETY”• Sarajevo, October

Sarajevo, October, 20–22. 2016 Sarajevo, October, “MUSIC IN SOCIETY”• The 10th International Symposium • THE COLLECTION OF PAPERS The 10th International Symposium “MUSIC IN SOCIETY” Sarajevo, October, 20–22. 2016 THE COLLECTION OF PAPERS • THE COLLECTION OF PAPERS “MUSIC IN SOCIETY” THE COLLECTION OF PAPERS Editors: Amra Bosnić and Naida Hukić Reviewers: Dr. Jelena Beočanin, Faculty of Philology and Arts, University of Kragujevac, Serbia Dr. Ivan Čavlović, Academy of Music, University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Dr. Dean Duda, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Zagreb, Croatia Dr. Scottt Gleason, Columbia University Department of Music, United States of America Dr. Dimitrije O. Golemović, Faculty of Music in Belgrade, Serbia Dr. Fatima Hadžić, Academy of Music, University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Dr. Refik Hodžić, Academy of Music, University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Dr. Vesna Ivkov, Academy of Arts, University of Novi Sad, Serbia Dr. Igor Karača, Oklahoma State University, United States of America Dr. Milorad Kenjalović, Academy of Arts, University of Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina Dr. Sanja Kiš Žuvela, Academy of Music, University of Zagreb, Croatia Dr. Marija Klobčar, Institute of Ethnomusicology in Ljubljana, Slovenia Dr. Lasanthi Manaranjanie Kalinga Dona, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia Dr. Indira Meškić, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Zenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina Dr. Irena Miholić, Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Research in Zagreb, Croatia Dr. Mladen Miličević, Loyola Marymount University Los Angeles, United States of America Dr. Lana Paćuka, Academy of Music, University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Dr. Dragica Panić Kašanski, Academy of Arts, University of Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina Dr. Milena Petrović, Faculty of Music in Belgrade, Serbia Dr. -

Pending Summary Case Detail Report As of 9/30/2017 JUDGE: CHARLES G CRAWFORD DEPENDENCY

Print Date: 10/19/2017 CLERK OF THE COURT Page 1 of 6 Print Time: 8:30 PM BREVARD COUNTY, FLORIDA Project 1872 CIRCUIT Pending Summary Case Detail Report as of 9/30/2017 JUDGE: CHARLES G CRAWFORD DEPENDENCY 1. CASES 1 TO 2 YEARS OLD A. ORIGINAL CASES Case Number Case Title Filing Dt Calendar Dt Last Pleading 05-2016-DP-000616-XXXX-XX BRAYDEN KRON 1/21/2016 11/27/2017 10365 10/11/2017 05-2016-DP-000686-XXXX-XX DEBRA JUSTICE 2/2/2016 10/25/2017 10169 10/19/2017 05-2016-DP-000780-XXXX-XX BRADLEY JAMES RIVERA 2/17/2016 10336 9/28/2017 05-2016-DP-000942-XXXX-XX CASSI MARIE HUTSENPILLER ET AL 3/11/2016 1/29/2018 5099 9/19/2017 05-2016-DP-001056-XXXX-XX SAMUEL HERRERA-ARTEAGA ET AL 4/3/2016 1/8/2018 9068 10/9/2017 05-2016-DP-001311-XXXX-XX DANIEL VALENTIN 5/11/2016 1/17/2018 10384 9/22/2017 05-2016-DP-001454-XXXX-XX ARES JAYDEN WHITE ET AL 6/9/2016 12/19/2017 8243 10/16/2017 05-2016-DP-001492-XXXX-XX ERIN RENEE BRANHAM 6/14/2016 10/24/2017 10169 10/19/2017 05-2016-DP-001542-XXXX-XX KYLE ANTHONY GEIMER ET AL 6/22/2016 10/18/2017 11065 10/18/2017 05-2016-DP-001646-XXXX-XX KAMMIE MCINTOSH 7/12/2016 3/28/2018 11065 10/2/2017 05-2016-DP-001696-XXXX-XX BRANDON HERNANDEZ GOMEZ ET AL 7/21/2016 1/29/2018 8603 10/17/2017 05-2016-DP-001815-XXXX-XX CHEYENNE HALL 8/18/2016 2/21/2018 8241 10/12/2017 05-2016-DP-002016-XXXX-XX YNELIAH JOSHAUNNA A DURRING 9/17/2016 11/27/2017 11065 9/29/2017 Sub-Total of Cases: 13 B. -

96Th Annual Honors Convocation

96TH ANNUAL HONORS CONVOCATION MARCH 24, 2019 2:00 P.M. HILL AUDITORIUM This year marks the 96th Honors Convocation held at the University of Michigan since the first was instituted on May 13, 1924, by President Marion LeRoy Burton. On these occasions, the University publicly recognizes and commends the undergraduate students in its schools and colleges who have earned distinguished academic records or have excelled as leaders in the community. It is with great pride that the University honors those students who have most clearly and effectively demonstrated academic excellence, dynamic leadership, and inspirational volunteerism. The Honors Convocation ranks with the Commencement Exercises as among the most important ceremonies of the University year. The names of the students who are honored for out- standing achievement this year appear in this program. They include all students who have earned University Honors in both Winter 2018 and Fall 2018, plus all seniors who have earned University Honors in either Winter 2018 or Fall 2018. The William J. Branstrom Freshman Prize recipients are listed, as well — recognizing first year undergraduate students whose academic achievement during their first semester on campus place them in the upper five percent of their school or college class. James B. Angell Scholars — students who receive all “A” grades over consecutive terms — are given a special place in the program. In addition, the student speaker is recognized individually for exemplary contributions to the University community. To all honored students, and to their parents, the University extends its hearty congratulations. Martin A. Philbert • Provost and Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs Honored Students Honored Faculty Faculty Colleagues and Friends of the University It is a pleasure to welcome you to the 96th University of Michigan Honors Convocation. -

Donor Listings

Fiscal Year 2012 - Donor Listings 10 M Marine, LLC 3RD Point Foundation A. P. Keller, Inc. A.S.I Federal Credit Union Mr. and Mrs. Thomas J. Aab Deacon and Mrs. David P. Aaron AARP Belle Chasse Chapter 4034 Mr. and Mrs. Donald B. Abadie Mr. and Mrs. Donald P. Abadie Dr. and Mrs. Francis R. Abadie Mr. and Mrs. Jack Abadie Mr. and Mrs. Lloyd J. Abadie, Sr. Mr. and Mrs. Rene C. Abadie Mr. Robert J. Abadie Mr. and Mrs. Tony Abadie Mr. and Mrs. William C. Abadie, Sr. Ms. Yvonne C. Abadie Mr. and Mrs. Jose A. Abadin, Jr. Ms. Miriam L. Abate Mr. and Mrs. John W. Abbott Mr. Gregory S. Abel Mr. and Mrs. Rodney J. Abele, Jr. Ms. Karen Abell Ms. Helen L. Aber Mr. Desmond Ables *Deceased Fiscal Year 2012 - Donor Listings Mr. and Mrs. Robert H. Abney, Jr. Ms. Dianna L. Abrahms Mr. and Mrs. Herman J. Abry Academy of Our Lady Acadian Ambulance Ms. M. A. Acebal Mr.* and Mrs. Charles A. Achee, Jr. Mrs. Jane Ackers Mr. and Mrs. Deryl Ackley Ms. Greta M. Acomb Mr. and Mrs. Robert B. Acomb, Jr. Mr. and Mrs. Donald F. Acosta, Sr. Ms. Lynne L. Acosta Mr. and Mrs. Wayne T. Acosta Mr. and Mrs. Alvin J. Adam, Jr. Mr. Michael V. Adam Mr. and Mrs. Robert L. Adam Mr. and Mrs. Albert A. Adams Mr. Brad A. Adams Mr. and Mrs. Byron A. Adams, Jr. Deacon and Mrs. Dennis F. Adams Mr. and Mrs. Edward L. Adams Mr. and Mrs. Leo R.