MUSIC in SOCIETY”• Sarajevo, October

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Knee-Fiddles in Poland: Multidimensional Bridging of Paradigms

Knee-Fiddles in Poland: Multidimensional Bridging of Paradigms Ewa Dahlig-Turek Abstract: Knee-fiddles, i.e., bowed chordophones played in the vertical position, are an extinct group of musical instruments existing in the past in the Polish territory, known only from the few iconographic sources from the 17th and 19th century. Their peculiarity lies in the technique of shortening the strings – with the fingernails, and not with the fingertips. Modern attempts to reactivate the extinct tradition by introducing knee-fiddles to musical practice required several steps, from the reconstruction of the instruments to proposing a performance technique and repertoire. The process of reconstructing knee-fiddles and their respective performance practice turned out to be a multi-dimensional fusion of paradigms leading to the bridging of seemingly unconnected phenomena of different times (instrument), cultures (performance technique) or genres (repertoire): (1) historical fiddle-making paradigms have been converted into present-day folk fiddle construction for more effective playing (in terms of ergonomy and sound), (2) playing technique has been based on paradigms borrowed from distant cultures (in the absence of the local ones), (3) the repertoire has been created by overlapping paradigms of folk music and popular music in order to produce a repertoire acceptable for today’s listeners. Key words: chordophones, knee-fiddles, Polish folk music, fingernail technique. For more than a decade, we have been witnessing in Poland a strong activity of the “folky”1 music scene. By this term I understand music located at the intersection of folk music (usually Polish or from neighboring countries) and various genres of popular music. -

2017 Iedrc Hong Kong Conferences Abstract

2017 IEDRC HONG KONG CONFERENCES ABSTRACT Hong Kong December 28-30, 2017 Sponsored by Published by http://www.iedrc.org/ 2017 IEDRC HONG KONG CONFERENCES Table of Contents Items Pages Welcome Remarks 3 Conference Venue Information 4 Instructions for Publications 6 Instructions for Presentations 6 Conference Keynote Speakers 7-9 Time Schedule 10-11 Session 1: Education and Linguistics(13:00-15:15) 12-16 Venue: Phoenix (HS005-A, HS306-A, HS009, HS012-A, HS015, HS017, HS018, HS101, HS007) Session 2: Humanities and Social Sciences(15:30-18:30) 17-23 Venue: Phoenix (HS020, HS024-A, HS008-A, HD0012, HD0015, HD0016, HS029, HS030, HS031, HS032, HS028, HS034-A) Session 3: Economic and Management(17:15-18:30) 24-26 Venue: Unicorn (HD0014, HS014-A, HS002-A, HS303, HS006) Poster Session (HD0016) 26 Upcoming Conferences Information 27-29 Note 30 2 2017 IEDRC HONG KONG CONFERENCES Welcome Remarks On behalf IEDRC, we welcome you to Hong Kong to attend 2017 6th International Conference on Sociality and Humanities (ICOSH 2017), 2017 7th International Conference on History and Society Development (ICHSD 2017). We’re confident that over the three days you’ll get theoretical grounding, practical knowledge, and personal contacts that will help you build long-term, profitable and sustainable communication among researchers and practitioners working in a wide variety of scientific areas with a common interest in Sociality, Humanities, and History. On behalf of Conference Chair and all the conference committee, we would like to thank all the authors as well as the Program Committee members and reviewers. Their high competence, their enthusiasm, their time and expertise knowledge, enabled us to prepare the high-quality final program and helped to make the conference a successful event. -

Eva Dahlgren 4 Vast Resource of Information Not Likely Found in Much of Gay Covers for Sale 6 Mainstream Media

Lambda Philatelic Journal PUBLICATION OF THE GAY AND LESBIAN HISTORY ON STAMPS CLUB DECEMBER 2004, VOL. 23, NO. 4, ISSN 1541-101X Best Wishes French souvenir sheet issued to celebrate the new year. December 2004, Vol. 23, No. 4 The Lambda Philatelic Journal (ISSN 1541-101X) is published MEMBERSHIP: quarterly by the Gay and Lesbian History on Stamps Club (GLHSC). GLHSC is a study unit of the American Topical As- Yearly dues in the United States, Canada and Mexico are sociation (ATA), Number 458; an affiliate of the American Phila- $10.00. For all other countries, the dues are $15.00. All telic Society (APS), Number 205; and a member of the American checks should be made payable to GLHSC. First Day Cover Society (AFDCS), Number 72. Single issues $3. The objectives of GLHSC are to promote an interest in the col- There are two levels of membership: lection, study and dissemination of knowledge of worldwide philatelic material that depicts: 1) Supportive, your name will not be released to APS, ATA or AFDCS, and 6 Notable men and women and their contributions to society 2) Active, your name will be released to APS, ATA and for whom historical evidence exists of homosexual or bisex- AFDCS (as required). ual orientation, Dues include four issues of the Lambda Philatelic Journal and 6 Mythology, historical events and ideas significant in the his- a copy of the membership directory. (Names will be with- tory of gay culture, held from the directory upon request.) 6 Flora and fauna scientifically proven to having prominent homosexual behavior, and ADVERTISING RATES: 6 Even though emphasis is placed on the above aspects of stamp collecting, GLHSC strongly encourages other phila- Members are entitled to free ads. -

The Great Choral Treasure Hunt Vi

THE GREAT CHORAL TREASURE HUNT VI Margaret Jenks, Randy Swiggum, & Rebecca Renee Winnie Friday, October 31, 2008 • 8:00-9:15 AM • Lecture Hall, Monona Terrace Music packets courtesy of J.W. Pepper Music YOUNG VOICES Derek Holman: Rattlesnake Skipping Song Poem by Dennis Lee 5. From Creatures Great and Small From Alligator Pie Boosey & Hawkes OCTB6790 [Pepper #3052933] SSA and piano Vincent Persichetti: dominic has a doll e.e. cummings text From Four Cummings Choruses Op. 98 2-part mixed, women’s, or men’s voices Elkam-Vogel/Theodore Presser 362-01222 [Pepper #698498] Another recommendation from this group of choruses: maggie and milly and molly and may David Ott: Garden of Secret Thoughts From: Garden of Secret Thoughts Plymouth HL-534 [Pepper #5564810] 2 part and piano Other Recommendations: Geralad Finzi: Dead in the Cold (From Ten Children’s Songs Op. 1) Poems by Christina Rossetti Boosey & Hawkes [Pepper #1542752] 2 part and piano Elam Sprenkle: O Captain, My Captain! (From A Midge of Gold) Walt Whitman Boosey & Hawkes [Pepper #1801455] SA and piano Carolyn Jennings: Lobster Quadrille (From Join the Dance) Lewis Carroll Boosey & Hawkes [Pepper #1761790] SA and piano Victoria Ebel-Sabo: Blustery Day (The Challenge) Boosey & Hawkes [Pepper #3050515} unison and piano Paul Carey: Seal Lullaby Rudyard Kipling Roger Dean [Pepper #10028100} SA and piano Zoltán Kodály: Ladybird (Katalinka) Boosey & Hawkes [Pepper #158766] SSA a cappella This and many other Kodály works found in Choral works for Children’s and Female voices, Editio Musica Budapest Z.6724 MEN’S VOICES Ludwig van Beethoven: Wir haben ihn gesehen Christus am Ölberge (Franz Xavier Huber) Alliance AMP 0668 [Pepper # 10020264] Edited by Alexa Doebele TTB piano (optional orchestral score) WOMEN’S VOICES Princess Lil’uokalani, Arr. -

10. Turkey Lurkey

September- week 4: 3. Teach song #11 “Shake the Papaya” by rote. When the students can sing the entire song, use the song as the Musical Concepts: theme of a rondo. Choose or create rhythm patterns to perform as q qr h w variations between the singing of the theme. (You could choose create rondo three rhythm flashcards.) The final form will be: New Songs: Concept: A - sing 10. Turkey Lurkey CD1: 11 smd B - perform first rhythm pattern as many times as needed * show high/middle/low, derive solfa , teacher notates (8 slow beats or 16 fast ones) 11. Shake the Papaya CD1: 12-37 Calypso A - sing * create rondo using unpitched rhythm instruments or C - perform second rhythm pattern boomwhackers smd A - sing D - perform third rhythm pattern Review Songs: Concept: A - sing 8. Whoopee Cushion CD1: 8-9-35 d m s d’, round 9. Rocky Mountain CD1: 10-36 drm sl, AB form You can perform the rhythm patterns on unpitched percussion instruments or on Boomwhackers® (colored percussion tubes). General Classroom Music Lesson: 4. Assess individuals as they sing with the class. Have the children stand up in class list order. Play the song on the CD and have q qr Erase: Use first half of “Rocky Mountain.” the entire class sing. Listen to each child sing alone for a few The rhythm is written as follows. seconds and grade on your class list as you go. For the September assessment use #9 “Rocky Mountain.” qr qr | qr qr | qr qr | h | qr qr | qr qr | qr qr | h || Listening Resource Kit Level 3: Rhythm Erase: Put all eight measures on the board. -

Mladen Milicevic Received a BA (1982) and an MA

Mladen Milicevic received a B.A. (1982) and an M.A. (1986) in music composition and multimedia arts studying at The Music Academy of Sarajevo, in his native Bosnia- Herzegovina. In 1986 Mr. Milicevic came to the United States to study with Alvin Lucier at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, from which he received his masters in experimental music composition (1988). From the University of Miami in Florida, Mr. Milicevic received his doctorate in music composition in 1991, studying with Dennis Kam. For several summers, he also studied with Michael Czajkowski at the Aspen Music School. He was awarded numerous music prizes for his compositions in the former Yugoslavia as well as in Europe. Working in his homeland as a freelance composer for ten years, he composed for theater, films, radio and television, also receiving several prizes for this body of work. Since he moved to the United States in 1986, Mr. Milicevic has performed his live electronic music, composed for modern dances, made several experimental animated films and videos, set up installations and video sculptures, had exhibitions of his paintings, and scored for films. His academic interests are interdisciplinary and he has made many presentations at various international conferences on a wide range of topics such as music, film, aesthetics, semiology, sociology, education, artificial intelligence, religion, and cultural studies. Bizarrely enough, in 2003 he has scored film The Room which has now become an international phenomenon as the “worst” film ever made. Mr. Milicevic is Professor in the Recording Arts Department at Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles. He has been the Chair of the Recording Arts Department for 11 years, and in 2019 he stepped down from that position to become the first faculty member at Loyola Marymount University who teaches 100% online classes. -

Postignuća Isusovačkih Leksikografa Dopreporodnoga Razdoblja

FILOLOGIJA 58, Zagreb 2012 UDK 81'374:27-789.5 Pregledni članak Primljen 16.VIII.2010. Prihvaćen za tisak 24.XI.2011. Vladimir Horvat Fratrovac 40 HR-10000 Zagreb [email protected] POSTIGNUĆA ISUSOVAČKIH LEKSIKOGRAFA DOPREPORODNOGA RAZDOBLJA U ovom radu prikazujemo renesansnu Europu u povezanosti s isuso- vačkim humanizmom, jezikoslovljem i leksikografijom. Isusovci su sa svojim učenicima i suradnicima postigli brojne rezulate koji su velika postignuća i doprinosi svjetskoj i hrvatskoj leksikografiji. U Hrvatskoj dovoljno je spomenuti Bartola Kašića koji je udario temelje hrvatskom jezikoslovlju, a napisao i apologiju, jedan od prvih slavističkih tekstova. Uvod Isusovački red od svoga odobrenja u Rimu 1540. godine, uz dušobriž- ništvo, bavio se i misionarskim djelovanjem evangelizacije, i prosvjet- no-odgojnim radom na humanističkim načelima.1 Nakon prvog ekspe- rimentalnog izdanja Ratio studiorum o prosvjetno-odgojnim načelima g. 1586., slijedilo je drugo izdanje g. 1591., a treće i konačno izdanje Ratio studiorum — Isusovački obrazovni sustav objavljeno je u Rimu 1599.2 Dok se obrazovno djelovanje razvijalo u brojnim isusovačkim kolegijima pre- težno u Europi, misionarska se djelatnost razvijala u Indiji i Kini, Japanu i poslije naročito u Americi. Mnogi su isusovački misionari morali najprije učiti i proučavati dotad nepoznate urođeničke jezike, pa su zatim za njih sastavljali i prve rječnike i pisali prve gramatike. 1 Charles E. O´Neill, Jezuiti in humanizem, u zborniku simpozija Jezuiti na Sloven- skem, Ljubljana, 1992. 2 Čitav -

Das Grillparzer-Denkmal Im Wiener Volksgarten“

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Das Grillparzer-Denkmal im Wiener Volksgarten“ Verfasserin Mag. Rita Zeillinger angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 315 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Diplomstudium Kunstgeschichte Betreuerin Ao. Univ. – Prof. Dr. Ingeborg Schemper-Sparholz Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung ................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Motiv und Überlegungen zur Themenwahl .......................................................... 4 2 Forschungsstand ....................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Quellen ............................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Literatur .............................................................................................................. 7 3 Äußere Umstände ...................................................................................................... 9 3.1 Politische und gesellschaftliche Hintergründe ..................................................... 9 3.2 Beschluss der Denkmalerrichtung .....................................................................12 4 Das Denkmal und seine Verortung ...........................................................................22 4.1 Entstehung der Wiener Ringstraße ....................................................................22 4.2 Positionierung -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

Jazzette, Jazz 91.9 WCLK Monthly Newsletter Page 2

Come along with Jazz 91.9 WCLK as we spread Holiday Joy with special programming and outreach this holiday season. We all know how hectic the hustle and bustle of the holidays can be with the shopping, gift giving, too many parties, and family and friends stopping by. FEATURE PAGE Lead Story 1 We invite you to set your dial to Jazz 91.9 and relax and #JazzUp with the perfect Cover Story 1 soundtrack for the holiday season. Community 2 Through the month of December, we Coverage are sprinkling our airwaves with Member 2 many of your favorite recorded Spotlight Christmas music selections. On Christmas we will present a special Station 3 musical celebration, Stand By Me Highlights featuring the Clark Atlanta University Events 3 Philharmonic Society and, Spelman and Morehouse Glee Clubs. Jazz Profile 4 On New Year’s Eve, enjoy Toast of Music Poll 4 Music Poll 4 the Nation, a broadcast of live Features 5 Jazz performances from various venues around the country. Wendy ▪ Tammy ▪ Aaron ▪ Reggie ▪ Shed ▪ The broadcast will include countdowns to New Year’s Dahlia ▪ Ray ▪ Juanita ▪ Barbara ▪ Kerwin ▪ Place your Joi ▪ Rob ▪ Marquis ▪ Morris ▪ Fonda ▪ in four distinct United Rivablue ▪ Jamal ▪ Debb ▪ logo here call States time zones. Jay ▪ Rodney (404) 880 - 8277. Jazz 91.9 WCLK In 2014, Jazz 91.9 WCLK will roll out an assortment Affiliations of special events in what is to be a yearlong observance that will symbolize the 40 years of excellence to the community. We are humbled by the hundreds of thousands of listeners who have made this journey with us. -

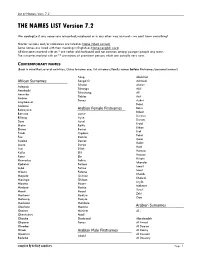

THE NAMES LIST Version 7.2 -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

List of Names, Vers. 7.2 THE NAMES LIST Version 7.2 We apologize if any names are misspelled, misplaced or in any other way misused – we can’t know everything! Shorter versions and/or nicknames are listed as Name (Short version) Some names are listed with their meaning in English as Name=english word All firstnames marked with an * are rather old-fashioned and not common among younger people any more. The surnames marked with an ** are names of prominent persons which are actually very rare. CONTEMPORARY NAMES (Bear in mind that several countries, China to name one, list surnames/family names before firstnames/personal names!) Song Abdullah African Surnames Songo’O Achmed Tchami Ahmet Adepoju Tchango Akif Amokachi Tchoutang Ali Amunike Tinkler Arif Andem Tovey Aykut Angibeaud Bahri Ardense Bekir Babayaro Arabian Female Firstnames Bülent Baruwa Aynur Durmus Billong Ayse Dursun Dosu Aysel Erdal Ekoku Belkis Erkan Etamé Berna Erol Finidi Cigdem Fahri Foe Damla Gazi Ikpeba Demet Halifi Ipoua Derya Halil Issa Dilek Hamza Kalla Elif Hassan Kanu Elo Hüsein Khumaleo Fahrie Iskender Kipketer Fatima Ismail Lobé Fatma Ismet M’butu Fehime Khalib Mapela Gulizar Khaled Masinga Gülcan Leyla Mboma Hacer Mehmet Mimboe Hatice Yusuf Moeti Hazel Zeki Moshoeu Hediye Ziya Motaung Hüeyla Moukoko Makbule Obafemi Medine Arabian Surnames Ohenen Mürüret Al - Okechukwu Nazli Okocha Shahrzad Abedzadeh Okpara Tanzu Al Awad Olembé Al Daeya Oliseh Arabian Male Firstnames Al Dokhy Opakuru Al Dossari Abdul Redebe Al Dossary Compiled By Krikkit Gamblers Page 1 List of Names, -

Society, Ethnicity, and Politics in Bosnia-Herzegovina

God. 36., br. 1., 331.-359. Zagreb, 2004 UDC: 323.1(497.6)(091) Society, Ethnicity, and Politics in Bosnia-Herzegovina MLADEN ANČIĆ Institute of Historical Sciences, Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Zadar, Republic of Croatia In his memoirs, general Sefer Halilović pays considerable attention to his part in preparing for Bosnian war during the winter of 1991-1992. Halilović organized and led the PL (Patriotic League), a paramilitary organization asso- ciated with the SDA (Stranka demokratske akcije – political party organized and led by Alija Izetbegović). The PL formed the core of the ABH (Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina), and Halilović therefore became the first commander of Bosnian Muslims’ armed forces in the summer of 1992.1 In the appendices to his memoirs, Halilović even included two documents pertaining to the SDA’s preparations for war in late 1991 and early 1992.2 In the first of these documents, would be general enumerated various tasks to be completed before the onset of war, including the creation of a military organi- zation and the identification of Bosnian communities according to their eth- nic makeup. “The ethnic structures of villages, local communities, urban and suburban neighborhoods are to be marked on maps,” the documents reads, “(Muslim and Croatian villages — full green circle, with a letter H adjoining Croatian villages, Serbian villages — blue circle)”. 3 In the second document, which is dated 25 Feb 92 — almost two months before large scale fighting broke out — Halilović defined the aim of the paramilitary organization he had just formed as protection of Bosnia-Herzegovina’s Muslim population.