Contents SEAGULL Theatre QUARTERLY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(AQAR) 2008-09 to the NAAC Authorities for Their Perusal

D V S College of Arts & Science, Shimoga. MOTTO OF D V S 'ADAPT AND EXCEL’ The institution adapts to the changing time and tries to excel in all aspects of the education. LOGO OF D V S The logo is framed keeping in mind the vision and mission of the institution. It also reflects the great ideals of education as perceived by the ancient Indian scholars. Teacher is placed at the centre as he is the key factor in the field of education. The rays around him suggest the spread of wisdom and enlightenment. The Vyasa Peetha in front of the Guru is the symbol of knowledge, which the institution spreads. The logo, which is circular in its shape, reflects wholeness and completeness. The swans on either side symbolize reason and thought. The swans, which rise above, suggest the upward movement of one's life from the lower level. This logo sums up the goal of our Institution. Therefore this logo has been adopted and sincerely emulated. || Panditaha Samadarshinaha || Explanation: A learned man has an integrated vision of life. AQAR – 2008-09 1 D V S College of Arts & Science, Shimoga. VISION To strive to become an institution of excellence in the field of higher education, to provide value-based, career oriented education to ensure integrated development of human potential for the service of mankind. MISSION Our mission is to realize our vision through 1. Promoting and facilitating education in conformity with the statutory and regulatory requirements. 2. Planning and establishing necessary infrastructure and learning resources. 3. Supporting faculty development programmes and continuing education programs. -

Dist. Name Name of the NGO Registration Details Address Sectors Working in Shimoga Vishwabharti Trust 411, BOOK NO. 1 PAGE 93/98

Dist. Name Name of the NGO Registration details Address Sectors working in Agriculture,Animal Husbandry, Dairying & Fisheries,Biotechnology,Children,Education & NEAR BASAWESHRI TEMPLE, ANAVATTI, SORABA TALUK, Literacy,Aged/Elderly,Health & Family Shimoga vishwabharti trust 411, BOOK NO. 1 PAGE 93/98, Sorbha (KARNATAKA) SHIMOGA DIST Welfare,Agriculture,Animal Husbandry, Dairying & Fisheries,Biotechnology,Children,Civic Issues,Disaster Management,Human Rights The Shimoga Multipurpose Social Service Society "Chaitanya", Shimoga The Shimoga Multipurpose Social Service Society 56/SOR/SMG/89-90, Shimoga (KARNATAKA) Education & Literacy,Aged/Elderly,Health & Family Welfare Alkola Circle, Sagar Road, Shimoga. 577205. Shimoga The Diocese of Bhadravathi SMG-4-00184-2008-09, Shimoga (KARNATAKA) Bishops House, St Josephs Church, Sagar Road, Shimoga Education & Literacy,Health & Family Welfare,Any Other KUMADVATHI FIRST GRADE COLLEGE A UNIT OF SWAMY Shimoga SWAMY VIVEKANANDA VIDYA SAMSTHE 156-161 vol 9-IV No.7/96-97, SHIKARIPURA (KARNATAKA) VIVEKANANDA VIDYA SAMSTHE SHIMOGA ROAD, Any Other SHIKARIPURA-577427 SHIMOGA, KARNATAKA Shimoga TADIKELA SUBBAIAH TRUST 71/SMO/SMG/2003, Shimoga (KARNATAKA) Tadikela Subbaiah Trust Jail Road, Shimoga Health & Family Welfare NIRMALA HOSPITALTALUK OFFICE ROADOLD Shimoga ST CHARLES MEDICAL SOCIETY S.No.12/74-75, SHIMOGA (KARNATAKA) Data Not Found TOWNBHADRAVATHI 577301 SHIMOGA Shimoga SUNNAH EDUCATIONAL AND CHARITABLE TRUST E300 (KWR), SHIKARIPUR (KARNATAKA) JAYANAGAR, SHIKARIPUR, DIST. SHIMOGA Education & Literacy -

Study of Small Schools in Karnataka. Final Report.Pdf

Study of Small Schools in Karnataka – Final Draft Report Study of SMALL SCHOOLS IN KARNATAKA FFiinnaall RReeppoorrtt Submitted to: O/o State Project Director, Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, Karnataka 15th September 2010 Catalyst Management Services Pvt. Ltd. #19, 1st Main, 1st Cross, Ashwathnagar RMV 2nd Stage, Bangalore – 560 094, India SSA Mission, Karnataka CMS, Bangalore Ph.: +91 (080) 23419616 Fax: +91 (080) 23417714 Email: raghu@cms -india.org: [email protected]; Website: http://www.catalysts.org Study of Small Schools in Karnataka – Final Draft Report Acknowledgement We thank Smt. Sandhya Venugopal Sharma,IAS, State Project Director, SSA Karnataka, Mr.Kulkarni, Director (Programmes), Mr.Hanumantharayappa - Joint Director (Quality), Mr. Bailanjaneya, Programme Officer, Prof. A. S Seetharamu, Consultant and all the staff of SSA at the head quarters for their whole hearted support extended for successfully completing the study on time. We also acknowledge Mr. R. G Nadadur, IAS, Secretary (Primary& Secondary Education), Mr.Shashidhar, IAS, Commissioner of Public Instruction and Mr. Sanjeev Kumar, IAS, Secretary (Planning) for their support and encouragement provided during the presentation on the final report. We thank all the field level functionaries specifically the BEOs, BRCs and the CRCs who despite their busy schedule could able to support the field staff in getting information from the schools. We are grateful to all the teachers of the small schools visited without whose cooperation we could not have completed this study on time. We thank the SDMC members and parents who despite their daily activities were able to spend time with our field team and provide useful feedback about their schools. -

Ajoka Theatre As an Icon of Liberal Humanist Values

Review of Education, Administration and Law (REAL) Vol. 4, (1) 2021, 279-286 Ajoka Theatre as an Icon of Liberal Humanist Values a b c d Ambreen Bibi, Saimaan Ashfaq, Qazi Muhammad Saeed Ullah, Naseem Abbas a PhD Scholar / Associate Lecturer, Department of English, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan Email: [email protected] b Associate Lecturer, Department of English, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan Email: [email protected] c Associate Lecturer, Department of English, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan. Email: [email protected] d Visiting Lecturer, Department of English, BZU, Multan, Pakistan Email: [email protected] ARTICLE DETAILS ABSTRACT History: There are multiple ways of transferring human values, cultures and Accepted 23 March 2021 history from one generation to another. Literature, Art, Paintings and Available Online March 2021 Theatrical performances are the real reflection of any civilization. In the history of subcontinent, theatres played a vital role in promoting the Keywords: Pakistani and Indian history; Mughal culture and traditions. Pakistani Ajoka Theatre, Liberal theatre, “Ajoka” played significant role to propagate positive, Humanism, Performance, humanitarian and liberal humanist values. This research aims to Culture, Dictatorship investigate the transformation in the history of Pakistani theatre specifically the “Ajoka” theatre that was established under the JEL Classification: government of military dictatorship in Pakistan in the late nineteenth L82 century. It was not a compromising time for the celebration of liberal humanist values in Pakistan as the country was under the rules of military dictatorship. The present study is intended to explore the DOI: 10.47067/real.v4i1.135 dissemination of liberal humanist values in the plays and performances of “Ajoka” theatre. -

Charaka Women's Multipurpose Cooperative Society1

WORKING PAPER NO: 333 Charaka Women’s Multipurpose Cooperative Society1 BY Rajalaxmi Kamath Assistant Professor, Centre for Public Policy Indian Institute of Management Bangalore Bannerghatta Road, Bangalore – 5600 76 Ph: 080-26993748 [email protected] & Smita Ramanathan Research Associate Indian Institute of Management Bangalore Bannerghatta Road, Bangalore – 5600 76 [email protected] Year of Publication 2011 1 Charaka Women’s Multipurpose Cooperative Society1. Charaka Women’s Multipurpose Cooperative Society. 1. Background We have been patrons of the Desi Apparel Stores at South End Circle in Bangalore, where we have been getting our handloom jubbas (kurtas) and other ready-to-wear cotton and handloom garments at very reasonable prices. We came to know that the main production unit for Desi is a rural women’s cooperative society called Charaka, based in the village of Heggodu in Shivamogga district of Karnataka. Charaka, we were told, was an initiative of the Kannada playwright and author Prasanna. The question of what makes successful cooperatives tick had always intrigued us and also wanting to know more about the jubbas that we liked wearing, we gathered information about Charaka and reached Heggodu for the first time in April 2009. The first impression of Charaka was very soothing to our jaded, urban eyes. Rustic, red mud and brick structures with artistic drawing on panels (which we later came to know was a folk-art called hase-kale), all around a huge banyan tree with chirpy young women ambling purposefully across the place. Since that day, we have been visiting Charaka often, and we have been drawn to the spirit of Charaka and the lively women who own and run that Institution. -

KSWTC List of Polling Stations

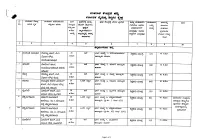

m.C7IR1 "fO~c.1 1111"1. ~ wmr6J.. 1I1.G).. a~wa t'! r--:~::;-.~----:ilJ3:=.s~ca=-cd:;-:"ff:i:~:-:-oo::::;,",;---r--:ilJ=.s;::ca=::;cd--:~=iid;::F"-;:;-a·:\J:;-ru=~:;---'--=ilJ:;-:-.s~-r--:m::;...,::;EfO":"H::;:1":;-.--:a:t~j"·.F.~~::".""·"~tljli~";t;~r~"~Kf,nri1'Ja'I1~·-r~c-:~~-=a:iJL~::;:Cll=:d:;::O:---'-::::;ilJ::-:;5:;:ca=d;:;d:-r--ilJ=;5:;-:-ri;-;-~·id--'---il;i-:-oe>-----. ;Go. '<llruii3~ ~ v'~dI:iO ~;Gru "ffeoSO l!f~drt l!fJJlrMt).J rnl'l~~e t!>q1iJel r..hlJd ;5OJiidOJ .o~~C8F" .gill" mol:l~9dOrl ;Gom~ ilJ.scad 'l.3.~e. Clloddri"doJ.lf'/ ~~a;!rcle t!>rpiJel ecrl:rnca;G ri~~M 'OI~0ctq., vel". !wo.l.wort ~~a;!rcle dewao riO"i, nd~M~ ~d 2 3 4 6 7 8 ." 9 10 <\:ldctOa3 Od~~d dc:J~~ iDdd", c:JJ~ 20 121 40 -!.~e. c:JQC><\:l<ti'flc;l, 'l.3.~e. <\:ldctOa3Od~~d 2 20 c:JJeE30rf iDdd", '1'llM idom~ 2, ;50eTlo ~~v'v 400 50 -!.~e. eroc;lc:J~1T.l~Od5 5Qe5, 'l.3.~e. 11iJiI~F" <35ei5d 3 dc:J~~ iDdd", c:JJ~ 20 '1'llM ;do&t~ 3, Tl.r.liidoJ~~v'v 278 80 -!.~e. c:JQC><\:l<ti'flc;l, 5J;)c;l 'l.3.~~. ili.r.JC8< 4 o.>~5> 5Qe5 c:JJeE3orf 20 e;reM ;dom~ 4, v'ri.Jadv ~~u'v 848 40 -!.~e. iDdd", c:JJ~ c:JQC><\:leifelc;l, 'l.3.~e. e5.r.lC8F" E3.i').d~ 5d.JddJ 5 20 c:JJeE3orf iDdd", c:JJ~ e;reM ;do&t~ 5, ~e)orleO ~~v'v 133 60 -!.~e. -

Legend Malaluru Talluru

Village Map of Shivamogga District, Karnataka µ Bilagalikoppa Binkavalli Bilagale Alahalli Devara HosakoppaShankarikoppa Arathalagadde Shakunahalli Sabara Soornagi Shanthapura Yadamata Thuyilakoppa Thoravandha Kodikoppa Bommarasikoppa Talagadde Forest Mallasamudra Moodidoddikoppa Dwarahalli Agasanahalli Kamaruru Thalagundli Madhapura T. Mooguru Ujjanipura JADE Mallapura Kallukoppa Neerlagi Kodihalli MangapuraThelagadde Kachavi Shanuvalli Lakkavalli Vitalapura Mayikoppa Hurulikoppa Jade Devasthana Hakkalu Jigarikoppa Hurali Hurali Bennegere Halekoppa Salagi Bankasana Hirechavati Jigarikoppa ANAVATTI Kubaturu Koppadahalu Bennuru Anavatti Chikkachavati Yammiganura Kaligeri Hanaji Hosakoppa Hosahalli Kodikoppa Chagaturu EnnikoppaEnnikoppa Barangi Yalivala VardhikoppaThumarikoppa Samanavalli Kamanavalli Kotekoppa Thalluru Belavanthanakoppa Jogihalli Kathavalli Ennikoppa Kenchikoppa Kunitheppa Haralakoppa Ennikoppa Iduru Hunasavalli Gummanahalu Badanakatte Kerehalli Siddihalli Haralikoppa Siddihalli Hanche Hirekaligodu Chikkayedagodu Thyavaratheppa Ginivala Basuru Shiddehalli Plantation Hasavi Thudaneeru Hireyadagodu Vrutthikoppa Chikkalagodu Thelagundli Puttanahalli Thalaguppa Kathuru Nellikoppa Jaddihalli Mathighatta Mangarasikoppa Hiremagadi Chikkamagadi Hunasekoppa Bettadakurli Forest Harishi Dyavanahalli Nittakki Negavadi Inam Agrahara Muchhadi Mallenahalli Kamaruru Gendla Bettadakurli Gangavalli Kuntagalale Sindli Sampagodu Thatthuru Haya Bandalike Mutthahalli Kolaga Shankrikoppa Bommenahalli Kanthanahalli Yalagere Malavalli Mangalore -

Shahid NADEEM, Pakistan

Message for World Theatre Day 2020 by Shahid NADEEM 27 March 2020 English (original) Shahid NADEEM, Pakistan Theatre as a Shrine It is a great honour for me to write the World Theatre Day 2020 Message. It is a most humbling feeling but it is also an exciting thought that Pakistani theatre and Pakistan itself, has been recognized by the ITI, the most influential and representative world theatre body of our times. This honour is also a tribute to Madeeha Gauhar1, theatre icon and Ajoka Theatre2 founder, also my life partner, who passed away two years ago. The Ajoka team has come a long, hard way, literally from Street to Theatre. But that is the story of many a theatre group, I am sure. It is never easy or smooth sailing. It is always a struggle. I come from a predominantly Muslim country, which has seen several military dictatorships, the horrible onslaught of religious extremists and three wars with neighbouring India, with whom we share thousands of years of history and heritage. Today we still live in fear of a full-blown war with our twin-brother neighbour, even a nuclear war, as both countries now have nuclear weapons. We sometimes say in jest; “bad times are a good time for theatre”. There is no dearth of challenges to be faced, contradictions to be exposed and status quo to be subverted. My theatre group, Ajoka and I have been walking this tightrope for over 36 years now. It has indeed been a tight rope: to maintain the balance between entertainment and education, between searching and learning from the past and preparing for the future, between creative free expression and adventurous showdowns with authority, between socially critical and financially viable theatre, between reaching out to the masses and being avant-garde. -

Women Who Remember

About Us Online advertisement tariff Friday, August 16, 2019 $ Search... % Home Editorials News Features Hot Features Audio # Good Times Home ∠ Features Women who remember by Ammara Ahmad — August 24, 2018 in Features, Latest Issue, August 24-30, 2018 Vol. XXX, No. 2 " 3 In the past few years after the death of my grandfather, I started seeking information regarding the Indian Partition and its survivors. I wanted to ensure the story is recorded. I am the third generation after Partition. And I was in for a pleasant surprise. Today, a lot of work being done to recover, record and preserve everything related to the “great divide” is being done by women. Perhaps because they found these empty spaces in the narratives to fill with their work, to give voice to the silence and create a mark where there is none. Maybe because family members shared more stories and details with their daughters and granddaughters. And probably because women could resonate with the stories of their predecessors more. Historian Ayesha Jalal Most of these women, like myself, are the daughters and granddaughters of the survivors. Almost all of them are based outside the Indian Subcontinent or educated abroad. Their work often transcends borders and takes a holistic approach. Most of them have traveled between India, Pakistan and Bangladesh for work, research or just leisure. Women are an integral part of the story of Partition. Particularly because of the violence, trauma, and silencing that they suffered during and after 1947. Maybe because family members shared more stories and details with their daughters and granddaughters. -

'Culture Is a Basic Need'

In Focus: Cultural Heritage Natural and man-made disasters draw an immediate response from humanitarian organisations around the world. They provide invaluable service meeting the immediate physical needs for the victims and survivors. But an important element is often missing from humanitarian efforts and policy: help restoring the objects that help people know who they are. The Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development established the Cultural Emergency Response program because it believes culture, too, is a basic need. ‘Culture is a basic need’ The Prince Claus Fund’s Special Program: Cultural Emergency Response Ginger da Silva and Iwana Chronis ing mosques illustrates how symbols of culture can have a therapeutic or healing function for people recovering from a catastrophe. n the spring of 2003, the bombing and invasion of Iraq unleashed a Iwave of lawlessness that led to the looting of the National Museum in Indonesia in general has a high awareness of its cultural past and an Baghdad. Thousands of priceless artefacts were stolen or destroyed. A impressive network of heritage organisations. But in the immediate wake year later, in December of 2004, an earthquake in the Indian Ocean trig- of the disaster it was difficult to find a representative of a cultural heritage gered a tsunami that killed hundreds of thousands of people and devas- group in Banda Aceh. So CER commissioned two journalists who were in tated coastal areas from Indonesia to East Africa. Whatever the source of the area to go scouting for potential projects. They identified a manuscript a catastrophe - floods, wars, earthquakes or other - the impact on people library and a music studio that held significant meaning for the commu- is profound and usually long term. -

ITI World Theatre Day 2020 Newsletter in English

World Theatre Day 2020 Campaign Preview HTML Source Plain-Text Email Details ITI Newsletter #2 - September 2020 Online version Shahid NADEEM, Pakistan – World Theatre Day Message Author for 2020 Dear Members of ITI, dear Friends of ITI, dear Readers It is our great pleasure and honour to officially announce that Shahid NADEEM from Pakistan, the leading playwright from Pakistan who has written over 50 plays, has been selected by the Executive Council to write the World Theatre Day Message for 2020. Born in Kashmir and raised in Pakistan, Shahid NADEEM is an outstanding playwright and a person who relentlessly advocates peace in his region and in the world, through his highly esteemed work and through his actions. Shahid NADEEM believes in the power of theatre and he uses it. When he was put into prison for being against the military dictatorship in his country, he created plays for the inmates of the notorious Mianwali prison. Independent of the burdens he had to experience when he was exiled and when his plays could no longer be shown, he believes in what he is doing, continues to write and follows his conviction. When Shahid NADEEM does something he does it with determination, accompanied by a special charm, a friendly attitude and with humour. That is why nowadays the doors are open to wherever he travels in his country or abroad such as India, the United States, United Kingdom and so on. These words are a glimpse about the author Shahid NADEEM, that the Executive Council of ITI has chosen for writing the message for World Theatre Day, which is celebrated since 1962 on the 27th of March all over the world. -

Bedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA

pincode officename districtname statename 560001 Dr. Ambedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 HighCourt S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Legislators Home S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Mahatma Gandhi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Rajbhavan S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vidhana Soudha S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 CMM Court Complex S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vasanthanagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Bangalore G.P.O. Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore Corporation Building S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore City S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Malleswaram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Palace Guttahalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Swimming Pool Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Vyalikaval Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Gavipuram Extension S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Mavalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Pampamahakavi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Basavanagudi H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Thyagarajnagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560005 Fraser Town S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 Training Command IAF S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 J.C.Nagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Air Force Hospital S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Agram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 Hulsur Bazaar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 H.A.L II Stage H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 Bangalore Dist Offices Bldg S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 K. G. Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Industrial Estate S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar IVth Block S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA