Regenerating Community Art, Community and Governance Identity, Security, Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

98Th ISPA Congress Melbourne Australia May 30 – June 4, 2016 Reimagining Contents

98th ISPA Congress MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA MAY 30 – JUNE 4, 2016 REIMAGINING CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF PEOPLE & COUNTRY 2 MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER FOR CREATIVE INDUSTRIES, 3 STATE GOVERNMENT OF VICTORIA MESSAGE FROM THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER, ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE 4 MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR OF PROGRAMMING, ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE 5 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR, INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (ISPA) 6 MESSAGE FROM THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER, INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (ISPA) 7 LET THE COUNTDOWN BEGIN: A SHORT HISTORY OF ISPA 8 MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA 10 CONGRESS VENUES 11 TRANSPORT 12 PRACTICAL INFORMATION 13 ISPA UP LATE 14 WHERE TO EAT & DRINK 15 ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE 16 THE ANTHONY FIELD ACADEMY SCHEDULE OF EVENTS 18 THE ANTHONY FIELD ACADEMY SPEAKERS 22 CONGRESS SCHEDULE OF EVENTS 28 CONGRESS PERFORMANCES 37 CONGRESS AWARD WINNERS 42 CONGRESS SESSION SPEAKERS & MODERATORS 44 THE ISPA FELLOWSHIP CHALLENGE 56 2016 FELLOWSHIP PROGRAMS 57 ISPA FELLOWSHIP RECIPIENTS 58 ISPA STAR MEMBERS 59 ISPA OUT ON THE TOWN SCHEDULE 60 SPONSOR ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 66 ISPA CREDITS 67 ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE CREDITS 68 We are committed to ensuring that everyone has the opportunity to become immersed in ISPA Melbourne. To help us make the most of your experience, please ask us about Access during the Congress. Cover image and all REIMAGINING images from Chunky Move’s AORTA (2013) / Photo: Jeff Busby ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF PEOPLE MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER FOR & COUNTRY CREATIVE INDUSTRIES, Arts Centre Melbourne respectfully acknowledges STATE GOVERNMENT OF VICTORIA the traditional owners and custodians of the land on Whether you’ve come from near or far, I welcome all which the 98th International Society for the Performing delegates to the 2016 ISPA Congress, to Australia’s Arts (ISPA) Congress is held, the Wurundjeri and creative state and to the world’s most liveable city. -

(AQAR) 2008-09 to the NAAC Authorities for Their Perusal

D V S College of Arts & Science, Shimoga. MOTTO OF D V S 'ADAPT AND EXCEL’ The institution adapts to the changing time and tries to excel in all aspects of the education. LOGO OF D V S The logo is framed keeping in mind the vision and mission of the institution. It also reflects the great ideals of education as perceived by the ancient Indian scholars. Teacher is placed at the centre as he is the key factor in the field of education. The rays around him suggest the spread of wisdom and enlightenment. The Vyasa Peetha in front of the Guru is the symbol of knowledge, which the institution spreads. The logo, which is circular in its shape, reflects wholeness and completeness. The swans on either side symbolize reason and thought. The swans, which rise above, suggest the upward movement of one's life from the lower level. This logo sums up the goal of our Institution. Therefore this logo has been adopted and sincerely emulated. || Panditaha Samadarshinaha || Explanation: A learned man has an integrated vision of life. AQAR – 2008-09 1 D V S College of Arts & Science, Shimoga. VISION To strive to become an institution of excellence in the field of higher education, to provide value-based, career oriented education to ensure integrated development of human potential for the service of mankind. MISSION Our mission is to realize our vision through 1. Promoting and facilitating education in conformity with the statutory and regulatory requirements. 2. Planning and establishing necessary infrastructure and learning resources. 3. Supporting faculty development programmes and continuing education programs. -

Annual Report 2017–2018

Annual Report 2017–2018 LIVE PERFORMANCE AUSTRALIA Cover: 2018 Helpmann Awards Act II Finale - Funny Girl - The Musical Inside: 2018 Helpmann Award Winner - Mona Foma In 2017, the Australian live performance industry generated $1.88 billion in ticket sales with over 23 million attendances - that is more than the combined attendances at AFL, NRL, soccer, Super Rugby and cricket.* ( LPA Ticket Attendance and Revenue Survey 2017) *Australian Sporting Attendances 2017, Stadiums Australia ANNUAL REPORT 2017 – 2018 1 Contents About About Page 3 President & Chief Executive’s Report 4 Major Achievements 5 Industry Wide Initiatives 6 Workplace Relations 8 Live Performance Australia (LPA) is the peak body for Australia’s Policy & Programs 10 live performance industry. Established 101 years ago in 1917 Annual Ticket Attendance and registered as an employers’ organisation under the Fair and Revenue Report 11 Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009, LPA has over 400 2017 Centenary Awards 12 Members nationally. We represent commercial producers, music 2018 Helpmann Awards 14 promoters, major performing arts companies, small to medium Member Services 18 companies, independent producers, major performing arts LPA Staff 20 centres, metropolitan and regional venues, commercial theatres, Financial Report 21 stadiums and arenas, arts festivals, music festivals, and service Executive Council 42 providers such as ticketing companies and technical suppliers. Members 44 Our membership spans from small to medium and not-for-profit Acknowledgements 46 organisations to large commercial entities. Current LPA Member Resources 48 LPA’s strategic direction is driven by our Members. LPA Members are leaders in our industry and their expertise is crucial to ensuring positive industry reform, whether by providing input to submissions or serving as a Member of LPA’s Executive Council. -

Dist. Name Name of the NGO Registration Details Address Sectors Working in Shimoga Vishwabharti Trust 411, BOOK NO. 1 PAGE 93/98

Dist. Name Name of the NGO Registration details Address Sectors working in Agriculture,Animal Husbandry, Dairying & Fisheries,Biotechnology,Children,Education & NEAR BASAWESHRI TEMPLE, ANAVATTI, SORABA TALUK, Literacy,Aged/Elderly,Health & Family Shimoga vishwabharti trust 411, BOOK NO. 1 PAGE 93/98, Sorbha (KARNATAKA) SHIMOGA DIST Welfare,Agriculture,Animal Husbandry, Dairying & Fisheries,Biotechnology,Children,Civic Issues,Disaster Management,Human Rights The Shimoga Multipurpose Social Service Society "Chaitanya", Shimoga The Shimoga Multipurpose Social Service Society 56/SOR/SMG/89-90, Shimoga (KARNATAKA) Education & Literacy,Aged/Elderly,Health & Family Welfare Alkola Circle, Sagar Road, Shimoga. 577205. Shimoga The Diocese of Bhadravathi SMG-4-00184-2008-09, Shimoga (KARNATAKA) Bishops House, St Josephs Church, Sagar Road, Shimoga Education & Literacy,Health & Family Welfare,Any Other KUMADVATHI FIRST GRADE COLLEGE A UNIT OF SWAMY Shimoga SWAMY VIVEKANANDA VIDYA SAMSTHE 156-161 vol 9-IV No.7/96-97, SHIKARIPURA (KARNATAKA) VIVEKANANDA VIDYA SAMSTHE SHIMOGA ROAD, Any Other SHIKARIPURA-577427 SHIMOGA, KARNATAKA Shimoga TADIKELA SUBBAIAH TRUST 71/SMO/SMG/2003, Shimoga (KARNATAKA) Tadikela Subbaiah Trust Jail Road, Shimoga Health & Family Welfare NIRMALA HOSPITALTALUK OFFICE ROADOLD Shimoga ST CHARLES MEDICAL SOCIETY S.No.12/74-75, SHIMOGA (KARNATAKA) Data Not Found TOWNBHADRAVATHI 577301 SHIMOGA Shimoga SUNNAH EDUCATIONAL AND CHARITABLE TRUST E300 (KWR), SHIKARIPUR (KARNATAKA) JAYANAGAR, SHIKARIPUR, DIST. SHIMOGA Education & Literacy -

Study of Small Schools in Karnataka. Final Report.Pdf

Study of Small Schools in Karnataka – Final Draft Report Study of SMALL SCHOOLS IN KARNATAKA FFiinnaall RReeppoorrtt Submitted to: O/o State Project Director, Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, Karnataka 15th September 2010 Catalyst Management Services Pvt. Ltd. #19, 1st Main, 1st Cross, Ashwathnagar RMV 2nd Stage, Bangalore – 560 094, India SSA Mission, Karnataka CMS, Bangalore Ph.: +91 (080) 23419616 Fax: +91 (080) 23417714 Email: raghu@cms -india.org: [email protected]; Website: http://www.catalysts.org Study of Small Schools in Karnataka – Final Draft Report Acknowledgement We thank Smt. Sandhya Venugopal Sharma,IAS, State Project Director, SSA Karnataka, Mr.Kulkarni, Director (Programmes), Mr.Hanumantharayappa - Joint Director (Quality), Mr. Bailanjaneya, Programme Officer, Prof. A. S Seetharamu, Consultant and all the staff of SSA at the head quarters for their whole hearted support extended for successfully completing the study on time. We also acknowledge Mr. R. G Nadadur, IAS, Secretary (Primary& Secondary Education), Mr.Shashidhar, IAS, Commissioner of Public Instruction and Mr. Sanjeev Kumar, IAS, Secretary (Planning) for their support and encouragement provided during the presentation on the final report. We thank all the field level functionaries specifically the BEOs, BRCs and the CRCs who despite their busy schedule could able to support the field staff in getting information from the schools. We are grateful to all the teachers of the small schools visited without whose cooperation we could not have completed this study on time. We thank the SDMC members and parents who despite their daily activities were able to spend time with our field team and provide useful feedback about their schools. -

Robyn Archer 4-15 July

GRIFFIN THEATRE COMPANY PRESENTS ROBYN ARCHER 4-15 JULY European Cabaret really began in Paris in the 1880s and While the word cabaret has been then rapidly spread to Vienna at the fin de siècle, thence to stretched over the last few decades to Zurich, St Petersburg, Barcelona, Munich and Berlin, cover comedy, review, variety and where it coincided with the rise of national socialism and burlesque, there have been recent sniffs provided a necessary platform for voicing concern and of a return to something more akin to the criticism. Que Reste-t’Il starts with songs from the 1880s form’s noble origins, with Tim Minchin’s in Paris, and Dancing on the Volcano covers that brief rapid response to George Pell as a good period when Berlin cabaret was at first light-headed with example. Perhaps as the times again relief after World War I, and then traced the dramatic become more fraught, more complex, descent into despair and horror. The power of serious more difficult to understand and to poets and composers to record such histories is negotiate, ‘ the art of small forms’ (as undeniable, and reinforces the words of Brecht’s poem: Peter Alternberg described cabaret) will come into its own again. My young son asks Will there be singing in the bad times? Robyn Archer AO Yes, there will be singing About the bad times When the cabaret form crossed into English language- speaking countries, it tended to morph into something A NOTE FROM more polite, such as revue, and its bite was less at politics and corruption, and more to social mores and foibles. -

Dr Robyn Archer AO

Dr Robyn Archer AO Citation for conferral of Doctor of Music (honoris causa) Ceremony 10, Monday 4 May 2015, 11:00am Chancellor, I present to you Robyn Archer. The award of the Degree of Doctor of Music (honoris causa) acknowledges Robyn Archer’s contributions as a singer, writer, composer, stage and artistic director, and public advocate of the arts in Australia and internationally. Robyn Archer was born in 1948 in Prospect, South Australia. She graduated from The University of Adelaide with a Bachelor of Arts (Honours) and Diploma of Education, and took up a full-time singing career in blues, jazz, rock and cabaret. Robyn Archer sang in the Australian premiere of Bertolt Brecht/Kurt Weill’s The Seven Deadly Sins to open “The Space” at the Adelaide Festival Centre in 1974. She subsequently played Jenny in Weill’s Threepenny Opera. Since then her name has been linked with the German cabaret songs of Weill, Eisler and Paul Dessau. Her one-woman cabaret A Star is Torn (which toured throughout Australia 1979-83 and played for a year in London’s West End) and her 1981 show The Pack of Women both became successful books and recordings. Archer has written and devised many works for the stage from The Conquest of Carmen Miranda to Songs From Sideshow Alley and Cafe Fledermaus. Her ties to Adelaide have remained strong: In 2008 her play Architektin, on the life of Margarete Schütte-Lihotsky, premiered at the Dunstan Playhouse at the Adelaide Festival Centre and she gave the annual Hawke Lecture at the Adelaide Festival Centre in 2013. -

Charaka Women's Multipurpose Cooperative Society1

WORKING PAPER NO: 333 Charaka Women’s Multipurpose Cooperative Society1 BY Rajalaxmi Kamath Assistant Professor, Centre for Public Policy Indian Institute of Management Bangalore Bannerghatta Road, Bangalore – 5600 76 Ph: 080-26993748 [email protected] & Smita Ramanathan Research Associate Indian Institute of Management Bangalore Bannerghatta Road, Bangalore – 5600 76 [email protected] Year of Publication 2011 1 Charaka Women’s Multipurpose Cooperative Society1. Charaka Women’s Multipurpose Cooperative Society. 1. Background We have been patrons of the Desi Apparel Stores at South End Circle in Bangalore, where we have been getting our handloom jubbas (kurtas) and other ready-to-wear cotton and handloom garments at very reasonable prices. We came to know that the main production unit for Desi is a rural women’s cooperative society called Charaka, based in the village of Heggodu in Shivamogga district of Karnataka. Charaka, we were told, was an initiative of the Kannada playwright and author Prasanna. The question of what makes successful cooperatives tick had always intrigued us and also wanting to know more about the jubbas that we liked wearing, we gathered information about Charaka and reached Heggodu for the first time in April 2009. The first impression of Charaka was very soothing to our jaded, urban eyes. Rustic, red mud and brick structures with artistic drawing on panels (which we later came to know was a folk-art called hase-kale), all around a huge banyan tree with chirpy young women ambling purposefully across the place. Since that day, we have been visiting Charaka often, and we have been drawn to the spirit of Charaka and the lively women who own and run that Institution. -

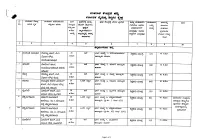

KSWTC List of Polling Stations

m.C7IR1 "fO~c.1 1111"1. ~ wmr6J.. 1I1.G).. a~wa t'! r--:~::;-.~----:ilJ3:=.s~ca=-cd:;-:"ff:i:~:-:-oo::::;,",;---r--:ilJ=.s;::ca=::;cd--:~=iid;::F"-;:;-a·:\J:;-ru=~:;---'--=ilJ:;-:-.s~-r--:m::;...,::;EfO":"H::;:1":;-.--:a:t~j"·.F.~~::".""·"~tljli~";t;~r~"~Kf,nri1'Ja'I1~·-r~c-:~~-=a:iJL~::;:Cll=:d:;::O:---'-::::;ilJ::-:;5:;:ca=d;:;d:-r--ilJ=;5:;-:-ri;-;-~·id--'---il;i-:-oe>-----. ;Go. '<llruii3~ ~ v'~dI:iO ~;Gru "ffeoSO l!f~drt l!fJJlrMt).J rnl'l~~e t!>q1iJel r..hlJd ;5OJiidOJ .o~~C8F" .gill" mol:l~9dOrl ;Gom~ ilJ.scad 'l.3.~e. Clloddri"doJ.lf'/ ~~a;!rcle t!>rpiJel ecrl:rnca;G ri~~M 'OI~0ctq., vel". !wo.l.wort ~~a;!rcle dewao riO"i, nd~M~ ~d 2 3 4 6 7 8 ." 9 10 <\:ldctOa3 Od~~d dc:J~~ iDdd", c:JJ~ 20 121 40 -!.~e. c:JQC><\:l<ti'flc;l, 'l.3.~e. <\:ldctOa3Od~~d 2 20 c:JJeE30rf iDdd", '1'llM idom~ 2, ;50eTlo ~~v'v 400 50 -!.~e. eroc;lc:J~1T.l~Od5 5Qe5, 'l.3.~e. 11iJiI~F" <35ei5d 3 dc:J~~ iDdd", c:JJ~ 20 '1'llM ;do&t~ 3, Tl.r.liidoJ~~v'v 278 80 -!.~e. c:JQC><\:l<ti'flc;l, 5J;)c;l 'l.3.~~. ili.r.JC8< 4 o.>~5> 5Qe5 c:JJeE3orf 20 e;reM ;dom~ 4, v'ri.Jadv ~~u'v 848 40 -!.~e. iDdd", c:JJ~ c:JQC><\:leifelc;l, 'l.3.~e. e5.r.lC8F" E3.i').d~ 5d.JddJ 5 20 c:JJeE3orf iDdd", c:JJ~ e;reM ;do&t~ 5, ~e)orleO ~~v'v 133 60 -!.~e. -

History of the Adelaide Festival of Arts

HISTORY OF THE ADELAIDE FESTIVAL OF ARTS Past Festivals and Posters Below is a collection of each Festival poster since its inception in 1960. The Adelaide Bank 2008 Festival of Arts was held from 29 February – 16 March, with Brett Sheehy as the Artistic Director for the second year in a row. One of the largest multi‐arts festivals in the world, the 2008 Adelaide Bank Festival of Arts attracted a 600,000‐strong audience and exceeded box office targets to achieve more than $2.5 million in ticket sales. Total income from the Festival and its associated events reached nearly $6 million. The event, which celebrated its 25th anniversary, featured 62 high quality international and national arts events and brought more than 700 of the world’s best artists to Adelaide, creating an unparalleled environment of cultural vibrancy, artistic endeavor and creativity. The Festival delivered to South Australia a total net economic benefit of $14.03 million in terms of income and ensured a positive social impact by enhancing the state’s reputation and image in the eyes of the event’s local, interstate and international attendees. There were a total of 300,000 free attendances of Northern Lights (up from150,000 in 2006). Northern Lights was funded by the Premier to continue an additional 2 weeks beyond it scheduled duration. 20,000 people attended the Northern Lights Opening Night – Ignition! 35,000 people attended Visual art exhibitions and 5000 attended Artists’ Week. The 2008 Adelaide Bank Festival of Arts achieved; • An increase of 8% over 2006 to create a direct net economic impact of $14.03million to the state • Interstate (8,025) and international (2,992) visitation increased by 105% to 11,017 over 2006. -

Legend Malaluru Talluru

Village Map of Shivamogga District, Karnataka µ Bilagalikoppa Binkavalli Bilagale Alahalli Devara HosakoppaShankarikoppa Arathalagadde Shakunahalli Sabara Soornagi Shanthapura Yadamata Thuyilakoppa Thoravandha Kodikoppa Bommarasikoppa Talagadde Forest Mallasamudra Moodidoddikoppa Dwarahalli Agasanahalli Kamaruru Thalagundli Madhapura T. Mooguru Ujjanipura JADE Mallapura Kallukoppa Neerlagi Kodihalli MangapuraThelagadde Kachavi Shanuvalli Lakkavalli Vitalapura Mayikoppa Hurulikoppa Jade Devasthana Hakkalu Jigarikoppa Hurali Hurali Bennegere Halekoppa Salagi Bankasana Hirechavati Jigarikoppa ANAVATTI Kubaturu Koppadahalu Bennuru Anavatti Chikkachavati Yammiganura Kaligeri Hanaji Hosakoppa Hosahalli Kodikoppa Chagaturu EnnikoppaEnnikoppa Barangi Yalivala VardhikoppaThumarikoppa Samanavalli Kamanavalli Kotekoppa Thalluru Belavanthanakoppa Jogihalli Kathavalli Ennikoppa Kenchikoppa Kunitheppa Haralakoppa Ennikoppa Iduru Hunasavalli Gummanahalu Badanakatte Kerehalli Siddihalli Haralikoppa Siddihalli Hanche Hirekaligodu Chikkayedagodu Thyavaratheppa Ginivala Basuru Shiddehalli Plantation Hasavi Thudaneeru Hireyadagodu Vrutthikoppa Chikkalagodu Thelagundli Puttanahalli Thalaguppa Kathuru Nellikoppa Jaddihalli Mathighatta Mangarasikoppa Hiremagadi Chikkamagadi Hunasekoppa Bettadakurli Forest Harishi Dyavanahalli Nittakki Negavadi Inam Agrahara Muchhadi Mallenahalli Kamaruru Gendla Bettadakurli Gangavalli Kuntagalale Sindli Sampagodu Thatthuru Haya Bandalike Mutthahalli Kolaga Shankrikoppa Bommenahalli Kanthanahalli Yalagere Malavalli Mangalore -

NINASAM TIRUGATA: Report 2012-13

NINASAM TIRUGATA: Report 2012-13 Vigada Vikramaraya: Tirugata 2012-13: Dir. by Manju Kodagu Mukkam Post Bombilwadi: Tirugata 2012-13: Dir. by Omkar K.R. 1 | P a g e Mukkam Post Bombilwadi: Tirugata 2012-13: Dir. by Omkar K.R. NINASAM TIRUGATA: Tirugata, the itinerant theatre repertory was established in 1985. Ninasam's idea of experimenting with such a project originated in the context of the decline of the professional theatre, and the limited achievements of the amateur theatre in post-independence Karnataka. It also aimed at testing whether it was possible to supplement the overall theatre activity in the state by presenting at a wide variety of centres, productions that combined the best elements of both professional and the amateur movements. It also provided the alumni of the Ninasam Theatre Institute a platform to test their innate talents and imbibed skills. A vast network of friends and contacts made it easier to organise the tour schedules. Trained actors and technicians appointed full time and paid; rehearsals and preparations for about three months; then, a long tour of about four months, encountering varied audiences all over Karnataka -- this, on broad lines, is Tirugata. Tirugata has every year taken three major productions of renowned classics and one children's play to centres with the minimum facilities of a 30ft. x 20 ft. stage area, power supply and accessibility by road. Financing itself almost totally independently, on gate collections, the repertory has had a predominantly rural and semi-rural audience. Most importantly it has firmly proved Ninasam's belief that such a project can take birth and continue to live, nurtured by mass support.