Charaka Women's Multipurpose Cooperative Society1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(AQAR) 2008-09 to the NAAC Authorities for Their Perusal

D V S College of Arts & Science, Shimoga. MOTTO OF D V S 'ADAPT AND EXCEL’ The institution adapts to the changing time and tries to excel in all aspects of the education. LOGO OF D V S The logo is framed keeping in mind the vision and mission of the institution. It also reflects the great ideals of education as perceived by the ancient Indian scholars. Teacher is placed at the centre as he is the key factor in the field of education. The rays around him suggest the spread of wisdom and enlightenment. The Vyasa Peetha in front of the Guru is the symbol of knowledge, which the institution spreads. The logo, which is circular in its shape, reflects wholeness and completeness. The swans on either side symbolize reason and thought. The swans, which rise above, suggest the upward movement of one's life from the lower level. This logo sums up the goal of our Institution. Therefore this logo has been adopted and sincerely emulated. || Panditaha Samadarshinaha || Explanation: A learned man has an integrated vision of life. AQAR – 2008-09 1 D V S College of Arts & Science, Shimoga. VISION To strive to become an institution of excellence in the field of higher education, to provide value-based, career oriented education to ensure integrated development of human potential for the service of mankind. MISSION Our mission is to realize our vision through 1. Promoting and facilitating education in conformity with the statutory and regulatory requirements. 2. Planning and establishing necessary infrastructure and learning resources. 3. Supporting faculty development programmes and continuing education programs. -

Dist. Name Name of the NGO Registration Details Address Sectors Working in Shimoga Vishwabharti Trust 411, BOOK NO. 1 PAGE 93/98

Dist. Name Name of the NGO Registration details Address Sectors working in Agriculture,Animal Husbandry, Dairying & Fisheries,Biotechnology,Children,Education & NEAR BASAWESHRI TEMPLE, ANAVATTI, SORABA TALUK, Literacy,Aged/Elderly,Health & Family Shimoga vishwabharti trust 411, BOOK NO. 1 PAGE 93/98, Sorbha (KARNATAKA) SHIMOGA DIST Welfare,Agriculture,Animal Husbandry, Dairying & Fisheries,Biotechnology,Children,Civic Issues,Disaster Management,Human Rights The Shimoga Multipurpose Social Service Society "Chaitanya", Shimoga The Shimoga Multipurpose Social Service Society 56/SOR/SMG/89-90, Shimoga (KARNATAKA) Education & Literacy,Aged/Elderly,Health & Family Welfare Alkola Circle, Sagar Road, Shimoga. 577205. Shimoga The Diocese of Bhadravathi SMG-4-00184-2008-09, Shimoga (KARNATAKA) Bishops House, St Josephs Church, Sagar Road, Shimoga Education & Literacy,Health & Family Welfare,Any Other KUMADVATHI FIRST GRADE COLLEGE A UNIT OF SWAMY Shimoga SWAMY VIVEKANANDA VIDYA SAMSTHE 156-161 vol 9-IV No.7/96-97, SHIKARIPURA (KARNATAKA) VIVEKANANDA VIDYA SAMSTHE SHIMOGA ROAD, Any Other SHIKARIPURA-577427 SHIMOGA, KARNATAKA Shimoga TADIKELA SUBBAIAH TRUST 71/SMO/SMG/2003, Shimoga (KARNATAKA) Tadikela Subbaiah Trust Jail Road, Shimoga Health & Family Welfare NIRMALA HOSPITALTALUK OFFICE ROADOLD Shimoga ST CHARLES MEDICAL SOCIETY S.No.12/74-75, SHIMOGA (KARNATAKA) Data Not Found TOWNBHADRAVATHI 577301 SHIMOGA Shimoga SUNNAH EDUCATIONAL AND CHARITABLE TRUST E300 (KWR), SHIKARIPUR (KARNATAKA) JAYANAGAR, SHIKARIPUR, DIST. SHIMOGA Education & Literacy -

Study of Small Schools in Karnataka. Final Report.Pdf

Study of Small Schools in Karnataka – Final Draft Report Study of SMALL SCHOOLS IN KARNATAKA FFiinnaall RReeppoorrtt Submitted to: O/o State Project Director, Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, Karnataka 15th September 2010 Catalyst Management Services Pvt. Ltd. #19, 1st Main, 1st Cross, Ashwathnagar RMV 2nd Stage, Bangalore – 560 094, India SSA Mission, Karnataka CMS, Bangalore Ph.: +91 (080) 23419616 Fax: +91 (080) 23417714 Email: raghu@cms -india.org: [email protected]; Website: http://www.catalysts.org Study of Small Schools in Karnataka – Final Draft Report Acknowledgement We thank Smt. Sandhya Venugopal Sharma,IAS, State Project Director, SSA Karnataka, Mr.Kulkarni, Director (Programmes), Mr.Hanumantharayappa - Joint Director (Quality), Mr. Bailanjaneya, Programme Officer, Prof. A. S Seetharamu, Consultant and all the staff of SSA at the head quarters for their whole hearted support extended for successfully completing the study on time. We also acknowledge Mr. R. G Nadadur, IAS, Secretary (Primary& Secondary Education), Mr.Shashidhar, IAS, Commissioner of Public Instruction and Mr. Sanjeev Kumar, IAS, Secretary (Planning) for their support and encouragement provided during the presentation on the final report. We thank all the field level functionaries specifically the BEOs, BRCs and the CRCs who despite their busy schedule could able to support the field staff in getting information from the schools. We are grateful to all the teachers of the small schools visited without whose cooperation we could not have completed this study on time. We thank the SDMC members and parents who despite their daily activities were able to spend time with our field team and provide useful feedback about their schools. -

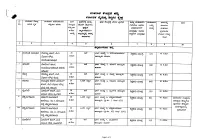

KSWTC List of Polling Stations

m.C7IR1 "fO~c.1 1111"1. ~ wmr6J.. 1I1.G).. a~wa t'! r--:~::;-.~----:ilJ3:=.s~ca=-cd:;-:"ff:i:~:-:-oo::::;,",;---r--:ilJ=.s;::ca=::;cd--:~=iid;::F"-;:;-a·:\J:;-ru=~:;---'--=ilJ:;-:-.s~-r--:m::;...,::;EfO":"H::;:1":;-.--:a:t~j"·.F.~~::".""·"~tljli~";t;~r~"~Kf,nri1'Ja'I1~·-r~c-:~~-=a:iJL~::;:Cll=:d:;::O:---'-::::;ilJ::-:;5:;:ca=d;:;d:-r--ilJ=;5:;-:-ri;-;-~·id--'---il;i-:-oe>-----. ;Go. '<llruii3~ ~ v'~dI:iO ~;Gru "ffeoSO l!f~drt l!fJJlrMt).J rnl'l~~e t!>q1iJel r..hlJd ;5OJiidOJ .o~~C8F" .gill" mol:l~9dOrl ;Gom~ ilJ.scad 'l.3.~e. Clloddri"doJ.lf'/ ~~a;!rcle t!>rpiJel ecrl:rnca;G ri~~M 'OI~0ctq., vel". !wo.l.wort ~~a;!rcle dewao riO"i, nd~M~ ~d 2 3 4 6 7 8 ." 9 10 <\:ldctOa3 Od~~d dc:J~~ iDdd", c:JJ~ 20 121 40 -!.~e. c:JQC><\:l<ti'flc;l, 'l.3.~e. <\:ldctOa3Od~~d 2 20 c:JJeE30rf iDdd", '1'llM idom~ 2, ;50eTlo ~~v'v 400 50 -!.~e. eroc;lc:J~1T.l~Od5 5Qe5, 'l.3.~e. 11iJiI~F" <35ei5d 3 dc:J~~ iDdd", c:JJ~ 20 '1'llM ;do&t~ 3, Tl.r.liidoJ~~v'v 278 80 -!.~e. c:JQC><\:l<ti'flc;l, 5J;)c;l 'l.3.~~. ili.r.JC8< 4 o.>~5> 5Qe5 c:JJeE3orf 20 e;reM ;dom~ 4, v'ri.Jadv ~~u'v 848 40 -!.~e. iDdd", c:JJ~ c:JQC><\:leifelc;l, 'l.3.~e. e5.r.lC8F" E3.i').d~ 5d.JddJ 5 20 c:JJeE3orf iDdd", c:JJ~ e;reM ;do&t~ 5, ~e)orleO ~~v'v 133 60 -!.~e. -

Legend Malaluru Talluru

Village Map of Shivamogga District, Karnataka µ Bilagalikoppa Binkavalli Bilagale Alahalli Devara HosakoppaShankarikoppa Arathalagadde Shakunahalli Sabara Soornagi Shanthapura Yadamata Thuyilakoppa Thoravandha Kodikoppa Bommarasikoppa Talagadde Forest Mallasamudra Moodidoddikoppa Dwarahalli Agasanahalli Kamaruru Thalagundli Madhapura T. Mooguru Ujjanipura JADE Mallapura Kallukoppa Neerlagi Kodihalli MangapuraThelagadde Kachavi Shanuvalli Lakkavalli Vitalapura Mayikoppa Hurulikoppa Jade Devasthana Hakkalu Jigarikoppa Hurali Hurali Bennegere Halekoppa Salagi Bankasana Hirechavati Jigarikoppa ANAVATTI Kubaturu Koppadahalu Bennuru Anavatti Chikkachavati Yammiganura Kaligeri Hanaji Hosakoppa Hosahalli Kodikoppa Chagaturu EnnikoppaEnnikoppa Barangi Yalivala VardhikoppaThumarikoppa Samanavalli Kamanavalli Kotekoppa Thalluru Belavanthanakoppa Jogihalli Kathavalli Ennikoppa Kenchikoppa Kunitheppa Haralakoppa Ennikoppa Iduru Hunasavalli Gummanahalu Badanakatte Kerehalli Siddihalli Haralikoppa Siddihalli Hanche Hirekaligodu Chikkayedagodu Thyavaratheppa Ginivala Basuru Shiddehalli Plantation Hasavi Thudaneeru Hireyadagodu Vrutthikoppa Chikkalagodu Thelagundli Puttanahalli Thalaguppa Kathuru Nellikoppa Jaddihalli Mathighatta Mangarasikoppa Hiremagadi Chikkamagadi Hunasekoppa Bettadakurli Forest Harishi Dyavanahalli Nittakki Negavadi Inam Agrahara Muchhadi Mallenahalli Kamaruru Gendla Bettadakurli Gangavalli Kuntagalale Sindli Sampagodu Thatthuru Haya Bandalike Mutthahalli Kolaga Shankrikoppa Bommenahalli Kanthanahalli Yalagere Malavalli Mangalore -

Bedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA

pincode officename districtname statename 560001 Dr. Ambedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 HighCourt S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Legislators Home S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Mahatma Gandhi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Rajbhavan S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vidhana Soudha S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 CMM Court Complex S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vasanthanagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Bangalore G.P.O. Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore Corporation Building S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore City S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Malleswaram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Palace Guttahalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Swimming Pool Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Vyalikaval Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Gavipuram Extension S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Mavalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Pampamahakavi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Basavanagudi H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Thyagarajnagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560005 Fraser Town S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 Training Command IAF S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 J.C.Nagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Air Force Hospital S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Agram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 Hulsur Bazaar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 H.A.L II Stage H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 Bangalore Dist Offices Bldg S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 K. G. Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Industrial Estate S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar IVth Block S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA -

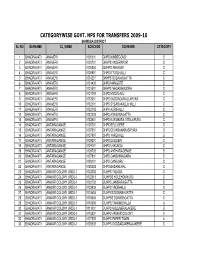

Shimoga Category Wise Primary & HS List

CATEGORYWISE GOVT. HPS FOR TRANSFERS 2009-10 SHIMOGA DISTRICT SL NO BLKNAME CL_NAME SCHCODE SCHNAME CATEGORY 1 BHADRAVATI ANAVERI 0100101 GHPS NIMBEGONDI C 2 BHADRAVATI ANAVERI 0100701 GKHPS VADERAPUR C 3 BHADRAVATI ANAVERI 0100804 GMHPS ANAVERI C 4 BHADRAVATI ANAVERI 0100901 GHPS ITTIGEHALLI C 5 BHADRAVATI ANAVERI 0101201 GKHPS GUDAMAGATTA C 6 BHADRAVATI ANAVERI 0101402 GHPS MANGOTE C 7 BHADRAVATI ANAVERI 0101501 GKHPS NAGASAMUDRA C 8 BHADRAVATI ANAVERI 0101702 GHPS MYDOLALU C 9 BHADRAVATI ANAVERI 0132001 GHPS GUDDADAMALLAPURA C 10 BHADRAVATI ANAVERI 0132101 GHPS SYDARAKALLAHALLI C 11 BHADRAVATI ANAVERI 0132102 GHPA ADRIHALLI C 12 BHADRAVATI ANAVERI 0132203 GHPS ARASANAGATTA C 13 BHADRAVATI ANAVERI 0133601 GHPS KURUBARA VITALAPURA C 14 BHADRAVATI ANTARAGANGE 0105701 GHPS BELLIGERE C 15 BHADRAVATI ANTARAGANGE 0107601 GHPS DEVARANARASIPURA B 16 BHADRAVATI ANTARAGANGE 0107907 GHPS YAREHALLI B 17 BHADRAVATI ANTARAGANGE 0109201 GHPS DODDERI C 18 BHADRAVATI ANTARAGANGE 0109701 GHPS UKKUNDA C 19 BHADRAVATI ANTARAGANGE 0109702 GHPS ANTHARAGENGE B 20 BHADRAVATI ANTARAGANGE 0127801 GHPS GANDHINAGARA C 21 BHADRAVATI ANTARAGANGE 0128101 GHPS GANGURU C 22 BHADRAVATI ANTARAGANGE 0128202 GHPS,BADANEHAL. C 23 BHADRAVATI ANWAR COLONY URDU-1 0102002 GUHPS TADASA C 24 BHADRAVATI ANWAR COLONY URDU-1 0102513 GUHPBS HOLEHONNURU C 25 BHADRAVATI ANWAR COLONY URDU-1 0102702 GUHPS JAMBARAGATTA C 26 BHADRAVATI ANWAR COLONY URDU-1 0103903 GUHPS YADEHALLI C 27 BHADRAVATI ANWAR COLONY URDU-1 0110603 GUHPGS DONABAGATTA C 28 BHADRAVATI ANWAR COLONY URDU-1 0110604 GUHPBS -

Ninasam End Line Report

Ninasam end line report MFS II country evaluations, Civil Society component Dieuwke Klaver1 Soma Wadhwa2 Marloes Hofstede1 Alisha Madaan2 Rajan Pandey2 Bibhu Prasad Mohapatra2 1 Centre for Development Innovation, Wageningen UR, The Netherlands 2 India Development Foundation, India Centre for Development Innovation Wageningen, February 2015 CONFIDENTIAL Report CDI-15-040 Klaver, D.C., Hofstede, M., Wadhwa S., Madaan A., Pandey R., Mohapatra B.P., February 2015, Ninasam end line report; MFS II country evaluations, Civil Society component, Centre for Development Innovation, Wageningen UR (University & Research centre) and International Development Foundation (IDF). Report CDI-15-040. Wageningen This report describes the findings of the end line assessment of the Indian theatre and arts organisation Ninasam that is a partner of Hivos. The evaluation was commissioned by NWO-WOTRO, the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research in the Netherlands and is part of the programmatic evaluation of the Co-Financing System - MFS II financed by the Dutch Government, whose overall aim is to strengthen civil society in the South as a building block for structural poverty reduction. Apart from assessing impact on MDGs, the evaluation also assesses the contribution of the Dutch Co-Funding Agencies to strengthen the capacities of their Southern Partners, as well as the contribution of these partners towards building a vibrant civil society arena. This report assesses Ninasam’s contribution to Civil Society in India and it used the CIVICUS analytical framework. It is a follow-up of a baseline study conducted in 2012. Key questions that are being answered comprise changes in the five CIVICUS dimensions to which Ninasam contributed; the nature of its contribution; the relevance of the contribution made and an identification of factors that explain Ninasam’s role in civil society strengthening. -

Regenerating Community Art, Community and Governance Identity, Security, Community

Identity, Security, Community Volume Seven, 2010 Seven, Volume ReGenerating Community Art, community and governance Identity, Security, Community Local–Global is a collaborative international journal concerned with the resilience and difficulties of contemporary social life. It draws together groups of researchers and practitioners located in different communities across the world to critically address issues concerning the relationship between the global and the local. It emphasises the following social themes and overarching issues that inform daily life over time and space: Authority–Participation Belonging–Mobility Equality–Wealth Distribution Freedom–Obligation Identity–Difference Inclusion–Exclusion Local Knowledges–Expert Systems Mediation–Disconnectedness Past–Present Power–Subjection Security–Risk Wellbeing–Adversity LOCAL–GLOBAL Volume Seven, 2010 Contents Foreword The great good neighbour: expanding the community role of arts organisations Excellence in civic engagement Lyz Crane 54 Kathy Keele 6 Research papers Editorial Mapping culture, creating places: collisions of science and art Martin Mulligan and Kim Dunphy 8 Chris Gibson 66 Lead essays The case for ‘socially engaged arts’: navigating art history, cultural development and arts funding narratives Finding the golden mean: the middle path between community imagination Marnie Badham 84 and individual creativity Anmol Vellani 14 How can the impact of cultural development work in local government be measured? Towards more effective planning and evaluation strategies Contemplating -

Government of Karnataka Directorate of Economics and Statistics

Government of Karnataka Directorate of Economics and Statistics Modified National Agricultural Insurance Scheme - GP-wise Average Yield data for 2013-14 Experiments Average Yield District Taluk Gram Panchayath Planned Analysed (in Kgs/Hect.) Crop : RICE Irrigated Season KHARIF 1 Shimoga 1 Bhadravathi 1 Sydarakallahalli 4 4 2898 2 Nimbegondi 4 4 3574 3 Anaveri 4 4 3790 4 Mangote 4 4 2981 5 Sidlipura 4 4 3045 6 Yadehalli 4 4 3136 7 Arahatholalu 4 4 3615 8 Holehonnuru 4 4 2322 9 Yemmehatti 4 4 3502 10 Kallihal 4 4 2895 11 Dasarakallahalli 4 4 2605 12 Marashettihalli 4 4 2829 13 Arebilachi 4 4 2596 14 Nagathibelagalu 4 4 2699 15 Attigunda 4 4 2546 16 Komaranahalli 4 4 3183 17 Thadasa 4 4 3073 18 Donabaghatta 4 4 3485 19 Bilaki 4 4 3394 20 Kallahalli 4 4 3325 21 Antharagange 4 4 3564 22 Dodderi 4 4 3143 23 Yarehalli 4 4 3197 24 Mavinakere 4 4 2812 25 Barandhuru 4 4 3081 26 Kambadala Hosuru 4 4 2826 27 Karehalli 4 4 2992 28 Aralikoppa 4 4 3126 29 Thavaraghatta 4 4 3107 30 Hiriyuru 4 4 2710 31 Bhadravathi CMC 4 4 3144 Page 1 of 9 Experiments Average Yield District Taluk Gram Panchayath Planned Analysed (in Kgs/Hect.) 2 Hosanagar 32 Purappemane 4 4 3641 33 Harathalu 4 4 2995 34 Jeni 4 4 2452 35 Maruthipura 4 4 2552 36 M. Guddekoppa 4 4 2500 37 Mumbaru 4 4 2342 38 Koduru 4 4 2321 39 Chikkajeni 4 4 3707 40 Baluru 4 4 4123 41 Rippanpete 4 4 3824 42 Kenchanala 4 4 4112 43 Arasalu 4 4 4129 44 Belluru 4 4 2817 45 Heddaripura 4 4 3109 46 Amrutha 4 4 3114 47 Humcha 4 4 3180 48 Sonale 4 4 3793 49 Melinabesige 4 4 2865 50 Nitturu 4 4 2051 51 Haridravathi -

Dist Name Taluk Name GP Name New Accoun No Bank Name

Annexure Dist_name taluk_name GP_name New Accoun no Bank_name Branch name IFSC code rel_amount Shimoga Sorab Agasanahalli 4278 Pragati Grameena Bank (PGB) Anavatti 2.00 Shimoga Thirthahalli Agumbe 19092200016309 Syndicate Bank Agumbe SYNB0001919 2.00 Shimoga Sorab Anavatti 4274 Pragati Grameena Bank (PGB) Anavatti 2.00 Shimoga Bhadravathi Anaveri 15775 Canara Bank Anaveri CNRB0000582 2.00 Shimoga Hosanagara Andagadooduru 64021979595 State Bank of Mysore (SBM) Mastikatte SBMY0040328 5.00 Shimoga Bhadravathi Arabilachi 6412 Pragati Grameena Bank (PGB) Kallihall 2.00 Shimoga Bhadravathi Arahatolalu 6406 Pragati Grameena Bank (PGB) Kallihall 2.00 Shimoga Bhadravathi Arakere 6404 Pragati Grameena Bank (PGB) Kallihall 2.00 Shimoga Sagar Aralagodu 14984 Canara Bank Kargal CNRB0000532 2.00 Shimoga Thirthahalli Aralasuralli SB01005699 Copraration Bank Aralasuralli CORP0000099 3.00 Shimoga Bhadravathi Aralihalli 521/6551 Pragati Grameena Bank (PGB) Aralihalli 2.00 Shimoga Bhadravathi Aralikoppa 12223 Indian Overseas Bank (IOB) Bhadravathi IOBA0000690 2.00 Shimoga Hosanagara Arasalu 17656 Canara Bank Rippan Pete CNRB0000534 1.00 Shimoga Bhadravathi Attigunda 521/6550 Pragati Grameena Bank (PGB) Aralihalli 2.00 Shimoga Hosanagara Balur 17645 Canara Bank Rippan Pete CNRB0000534 2.00 Shimoga Thirthahalli Basavani 5776515 Canara Bank Basavani CNRB0000577 2.00 Shimoga Thirthahalli Bejjavalli 102301010007324 Vijaya Bank Bejjavalli VIJB0001023 2.00 Shimoga Sorab Belavani 22974 Canara Bank Sorab CNRB0000573 2.00 Shimoga Hosanagara Belluru 17658 Canara Bank -

Tirthahalli.Pdf

MLA Constituency Name Mon Aug 24 2015 Tirthahalli Elected Representative :Kimmane Rathnakar Political Affiliation :Indian National Congress Number of Government Schools in Report :347 KARNATAKA LEARNING PARTNERSHIP This report is published by Karnataka Learning Partnership to provide Elected Representatives of Assembly and Parliamentary constituencies information on the state of toilets, drinking water and libraries in Government Primary Schools. e c r s u k o o S t o r e l e B i t o a h t t t T e i e W l l i n i W g o o o y y n T T i r r m k s a a s r r l m y n r i b b i o o r i i District Block Cluster School Name Dise Code C B G L L D CHIKKAMANGALORE KOPPA KAMMARADI GMHPS, KAMMARADI 29170200103 Well CHIKKAMANGALORE KOPPA KOPPA GMHPS ALEMANE 29170202801 Well GRAMANTARA CHIKKAMANGALORE NARASIMHARAJAPURA MUTHINA KOPPA GHPS BAIRAPURA 29170300503 Tap Water CHIKKAMANGALORE NARASIMHARAJAPURA MUTHINA KOPPA GLPS CHABBENADU 29170300302 Tap Water CHIKKAMANGALORE NARASIMHARAJAPURA MUTHINA KOPPA GLPS KORALAKOPPA 29170300402 Tap Water CHIKKAMANGALORE NARASIMHARAJAPURA SHETTIKOPPA GLPS HODEYALA 29170300202 Well CHIKKAMANGALORE NARASIMHARAJAPURA SHETTIKOPPA GLPS MUDUBA 29170300201 Tap Water SHIMOGA HOSANAGAR HOSANAGARA GHPS MUMBARU 29150204604 Well SHIMOGA HOSANAGAR HOSANAGARA GLPS BAISGUNDA 29150221001 Well SHIMOGA HOSANAGAR HOSANAGARA GLPS BEHALLI 29150213301 Well SHIMOGA HOSANAGAR HUMCHA GHPS ANEGADDE RASTE 29150214004 Well SHIMOGA HOSANAGAR HUMCHA GHPS BILLESWARA 29150214804 Tap Water SHIMOGA HOSANAGAR HUMCHA GHPS HUMCHA 29150214803 Well SHIMOGA