Tthe Capture of the Marienwerder Castle, Or Where the Teutonic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6r33q03k Author Eaton, Nicole M. Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg–Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 By Nicole M. Eaton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Yuri Slezkine, chair Professor John Connelly Professor Victoria Bonnell Fall 2013 Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg–Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 © 2013 By Nicole M. Eaton 1 Abstract Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948 by Nicole M. Eaton Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Yuri Slezkine, Chair “Exclave: Politics, Ideology, and Everyday Life in Königsberg-Kaliningrad, 1928-1948,” looks at the history of one city in both Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Russia, follow- ing the transformation of Königsberg from an East Prussian city into a Nazi German city, its destruction in the war, and its postwar rebirth as the Soviet Russian city of Kaliningrad. The city is peculiar in the history of Europe as a double exclave, first separated from Germany by the Polish Corridor, later separated from the mainland of Soviet Russia. The dissertation analyzes the ways in which each regime tried to transform the city and its inhabitants, fo- cusing on Nazi and Soviet attempts to reconfigure urban space (the physical and symbolic landscape of the city, its public areas, markets, streets, and buildings); refashion the body (through work, leisure, nutrition, and healthcare); and reconstitute the mind (through vari- ous forms of education and propaganda). -

EAA Meeting 2016 Vilnius

www.eaavilnius2016.lt PROGRAMME www.eaavilnius2016.lt PROGRAMME Organisers CONTENTS President Words .................................................................................... 5 Welcome Message ................................................................................ 9 Symbol of the Annual Meeting .............................................................. 13 Commitees of EAA Vilnius 2016 ............................................................ 14 Sponsors and Partners European Association of Archaeologists................................................ 15 GENERAL PROGRAMME Opening Ceremony and Welcome Reception ................................. 27 General Programme for the EAA Vilnius 2016 Meeting.................... 30 Annual Membership Business Meeting Agenda ............................. 33 Opening Ceremony of the Archaelogical Exhibition ....................... 35 Special Offers ............................................................................... 36 Excursions Programme ................................................................. 43 Visiting Vilnius ............................................................................... 57 Venue Maps .................................................................................. 64 Exhibition ...................................................................................... 80 Exhibitors ...................................................................................... 82 Poster Presentations and Programme ........................................... -

Archaeological Heritage in Lithuania After the 1990S: Defining, Protecting, Interpreting 161

Archaeological Heritage in Lithuania after the 1990s: Defining, Protecting, Interpreting 161 Archaeological Heritage in Lithuania after the 1990s: Defining, Protecting, Interpreting Justina Poškienė Abstract The paper seeks to present developments in the state system of archaeological heritage protection in Lithu- ania after the 1990s. National legislation was essentially modified twice: in 1994 and in 2004. As- pects of defining (inventarisation, assessment and listing in the national Register of Cultural Properties), protecting (requirements for archaeological heritage protection, regulations on archaeological excavations’ procedures) and the interpreting of archaeological heritage (preservation of archaeological remains in situ) are under consideration. Keywords: archaeological heritage, assessment, archaeological excavations, in situ. Santrauka Straipsnyje pristatomas Lietuvos archeologinis paveldas bei apžvelgiama valstybinė archeologinio paveldo apsaugos sistema po 1990 metų. Teisinis paveldo apsaugos reglamentavimas iš esmės keitėsi 1994 ir 2004 metais. Straipsnyje aptariami šie archeologinio paveldo apsaugos aspektai: apskaita (archeologinio paveldo vertinimas, įrašymas į Kultūros vertybių registrą, archeologinių objektų paveldosauginis statusas), ap- sauga (reikalavimai archeologiniams tyrimams, ardomųjų archeologinių tyrimų apimtys, archeologinių tyrimų kontrolės sistema) ir archeologinio paveldo interpretacija (archeologinio paveldo apsauga in situ). Recent_developments_FINAL.indd 161 9.1.2017 12:41:33 162 Justina Poškienė -

Strophomenide and Orthotetide Silurian Brachiopods from the Baltic Region, with Particular Reference to Lithuanian Boreholes

Strophomenide and orthotetide Silurian brachiopods from the Baltic region, with particular reference to Lithuanian boreholes PETRAS MUSTEIKIS and L. ROBIN M. COCKS Musteikis, P. and Cocks, L.R.M. 2004. Strophomenide and orthotetide Silurian brachiopods from the Baltic region, with particular reference to Lithuanian boreholes. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 49 (3): 455–482. Epeiric seas covered the east and west parts of the old craton of Baltica in the Silurian and brachiopods formed a major part of the benthic macrofauna throughout Silurian times (Llandovery to Pridoli). The orders Strophomenida and Orthotetida are conspicuous components of the brachiopod fauna, and thus the genera and species of the superfamilies Plec− tambonitoidea, Strophomenoidea, and Chilidiopsoidea, which occur in the Silurian of Baltica are reviewed and reidentified in turn, and their individual distributions are assessed within the numerous boreholes of the East Baltic, particularly Lithua− nia, and attributed to benthic assemblages. The commonest plectambonitoids are Eoplectodonta(Eoplectodonta)(6spe− cies), Leangella (2 species), and Jonesea (2 species); rarer forms include Aegiria and Eoplectodonta (Ygerodiscus), for which the new species E. (Y.) bella is erected from the Lithuanian Wenlock. Eight strophomenoid families occur; the rare Leptaenoideidae only in Gotland (Leptaenoidea, Liljevallia). Strophomenidae are represented by Katastrophomena (4 spe− cies), and Pentlandina (2 species); Bellimurina (Cyphomenoidea) is only from Oslo and Gotland. Rafinesquinidae include widespread Leptaena (at least 11 species) and Lepidoleptaena (2 species) with Scamnomena and Crassitestella known only from Gotland and Oslo. In the Amphistrophiidae Amphistrophia is widespread, and Eoamphistrophia, Eocymostrophia, and Mesodouvillina are rare. In the Leptostrophiidae Mesoleptostrophia, Brachyprion,andProtomegastrophia are com− mon, but Eomegastrophia, Eostropheodonta, Erinostrophia,andPalaeoleptostrophia are only recorded from the west in the Baltica Silurian. -

History of the Crusades. Episode 280. the Baltic Crusades. the Samogitian Crusade Part XIII

History of the Crusades. Episode 280. The Baltic Crusades. The Samogitian Crusade Part XIII. The Siege of Kaunas 1362. Hello again. Last week, we saw an effort by the Archbishop of Prague to convert the Lithuanian leaders to Christianity fail spectacularly, with the two pagan brothers making outrageous demands in return for their baptism, then laughing at and mocking the delegation when they objected. The upshot of this event was that converting the Lithuanians to Christianity by peaceful means was now permanently off the table as a goal to be pursued, so the only option left on the table was to convert the pagans by force. The Teutonic Order then spent time and effort constructing a bunch of new castles in Samogitia, which would provide a larger, more permanent Latin Christian presence in the region. Then, in the spring of the year 1362, fighting men from across Prussia, along with crusaders from Germany, Italy and England, gathered in Prussia, ready to head to Samogitia. This was to be a major Crusading expedition. William Urban describes it in his book "The Samogitian Crusade" as being a, and I quote, "huge force" end quote. Now you will notice that the Crusaders are departing in spring, not winter. That's because they don't need to ride across frozen rivers and swamps to get to Samogitia. Why don't they need to ride across frozen rivers and swamps to get to Samogitia? Well, because they are sailing there. Yes, in a novel break from tradition, the Grand Master and the Marshall of the Teutonic forces have come up with a plan to get everyone on board ships. -

The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade

Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 18 January 2017 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PRUSSIAN CRUSADE The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade explores the archaeology and material culture of the Crusade against the Prussian tribes in the thirteenth century, and the subsequent society created by the Teutonic Order that lasted into the six- teenth century. It provides the first synthesis of the material culture of a unique crusading society created in the south-eastern Baltic region over the course of the thirteenth century. It encompasses the full range of archaeological data, from standing buildings through to artefacts and ecofacts, integrated with writ- ten and artistic sources. The work is sub-divided into broadly chronological themes, beginning with a historical outline, exploring the settlements, castles, towns and landscapes of the Teutonic Order’s theocratic state and concluding with the role of the reconstructed and ruined monuments of medieval Prussia in the modern world in the context of modern Polish culture. This is the first work on the archaeology of medieval Prussia in any lan- guage, and is intended as a comprehensive introduction to a period and area of growing interest. This book represents an important contribution to promot- ing international awareness of the cultural heritage of the Baltic region, which has been rapidly increasing over the last few decades. Aleksander Pluskowski is a lecturer in Medieval Archaeology at the University of Reading. Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 -

Change of Efp Battalion Battle Group Command

FEBRUARY 2021. NO 2 (33). NATO'S PRESENCE THE NORTHERN STARS: TELEMARK BATTALION IN LITHUANIA IN SHORT Change of eFP Battalion WAR FOR FREEDOM OF LITHUANIA: battle Group command THE DECLARATION OF FEBRUARY 16, 1949 n February 10 the change of com- continue working on improving service con- mand ceremony of the NATO en- ditions, infrastructure and Host Nation Sup- hanced Forward Presence Battal- port provided to the NATO eFP battalion and Oion Battle Group (eFP BG) in Lithuania took other allies here in Lithuania," the Minister place at Rukla. The incoming eFP BG Lithua- said. nia Commander Lt Col Sebastian Hebisch "8 of 10 Lithuanian residents approve of al- from the 93rd Panzer Battalion of the Ger- lied troop presence on the territory of Lithua- man Armed Forces took over the duties from nia and think that the multinational NATO the outgoing LT Col Peer Papenbroock. The battalion constitutes a deterrence to hostile high-readiness multinational eFP BG capabi- states. We need to invest in our defence the lity of the Alliance was deployed in Lithuania same way we invest in fences around our four years ago as a collective and weighty con- houses, to protect us from threats or just for SPECIAL tribution of NATO allies to the enhancement the sake of it — because we need it to feel safe of security of the Baltic region. and take care of our backyard calmly. NATO CHALLENGES POSED BY Minister of National Defence of Lithuania allied presence in our country and the region RUSSIA FOR LITHUANIAN Arvydas Anušauskas thanked NATO allies is a clear and unambiguous message to the for their contributions to the NATO eFP BG threat keeping watch on the other side of the MILITARY SECURITY AND Lithuania and at the same time — to the secu- fence, it has tried to take advantage of our gul- THEIR PROSPECTS rity and efforts to strengthen not only Lithua- libility, or weakness, or sometimes blindness nia and the region but the whole Alliance. -

Program Opieki Nad Zabytkami Powiatu Kwidzynskiego Na Lata 2016�2019

Zał ącznik do uchwały Nr IX/54/2015 Rady Powiatu Kwidzy ńskiego z dnia 14 grudnia 2015 r. PROGRAM OPIEKI NAD ZABYTKAMI POWIATU KWIDZYNSKIEGO NA LATA 2016-2019 Wykonany na zlecenie i z środków Powiatu Kwidzyńskiego OPRACOWANIE: mgr Jolanta Barton-Piórkowska 2015 1 SPIS TREŚCI. 1. Wstęp………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...4 2. Podstawa prawna - Ustawa o ochronie zabytków i opiece nad zabytkami…………………………………...4-5 3. Uwarunkowanie prawne………………………………………………………………………………………………6-13 3.1. Obowiązek konstytucyjny ochrony zabytków 3.2. Ustawa o ochronie zabytków i opiece nad zabytkami 3.3. Inne ustawy i rozporządzenia 3.4. Prawo międzynarodowe 3.5. Zadania i kompetencje organów powiatu w zakresie ochrony zabytków 4. Uwarunkowania zewnętrzne ochrony dziedzictwa kulturowego……………………………………………13-18 4.1. Strategiczne cele polityki państwa w zakresie ochrony zabytków i opieki nad zabytkami 4.1.1. Krajowy Program Opieki nad Zabytkami na lata 2014-2017 4.1.2. Narodowa Strategia Rozwoju Kultury 4.2. Relacje powiatowego programu opieki nad zabytkami z dokumentami wykonanymi na poziomie województwa 4.2.1. Strategia Rozwoju Województwa Pomorskiego 4.2.2. Regionalny Program Operacyjny Województwa Pomorskiego 4.2.3. Plan zagospodarowania przestrzennego województwa pomorskiego 4.2.4. Wojewódzki program opieki nad zabytkami 2011-2014 5. Uwarunkowania wewnętrzne ochrony dziedzictwa kulturowego……………………………………………18-20 5.1. Strategia rozwoju powiatu kwidzyńskiego 5.2. Program ochrony środowiska powiatu kwidzyńskiego 5.3. Gminne programy opieki nad zabytkami 6. Charakterystyka krajobrazu kulturowego i zasobu dziedzictwa…………………………………………21-148 6.1. Zarys historii obszaru powiatu z wypunktowaniem najbardziej znaczących zjawisk i wydarzeń (kultura menonitów, okres regencji ) 6.2. Prezentacja krajobrazu kulturowego 6.3. Charakterystyka zasobu dziedzictwa: 6.3.1. Układy przestrzenne: urbanistyczne i ruralistyczne 6.3.2. -

How to Survive and Not to Get Bored in Kaunas

/ HOW TO SURVIVE AND NOT TO GET BORED IN KAUNAS / 004 DISCOVER VYTAUTAS MAGNUS UNIVERSITY 007_ We Were and Still Are Waiting for You to Come! 009_ Vytautas Magnus University – When? Where? Why? 012_ Facts and Figures About the University Survival guide: 014_ International Office – Ready to Help You How to survive and not to get bored in Kaunas 016 SURVIVAL GUIDE 018_ Arriving 019_ Incoming Student’s To-Do List Before Coming to VMU ? 059 Where to Eat Out and Have a Drink? 020_ Lithuanian Customs & Consular Information 064 Where to Spend Evenings & Nights? 023_ Reaching Kaunas & Travelling ored 068 What Should I Visit in Kaunas? B 026 Studying 072 Places Worth Your Attention @ VMU 2 027_ How to Design the Study Schedule? et 3 G 075 Kaunas for Keen Theatre Goers 028_ System of Credits & Grading @ VMU O 078 Information for Passionate Cinema Goers 030_ Lithuanian Language Courses T 080 Online News in [En] and [Ru] 033_ Library & Its Reading Rooms ot 080 Learn [Lt] is Easy if You Know How 034_ Academic Year – What & When? N 082 Culture Which Surrounds You in Kaunas 036 Living ow 084 Before You Leave 037_ Incoming Student’s To-Do List After Coming to VMU H 085 Incoming Student’s To-Do List Before Leaving VMU 038 Things You Should Know About the Dormitory of VMU 040 Life in a Dormitory – Some Rules, Tips & Tricks ? 042 Health Care and Insurance 086 DISCOVER KAUNAS 089 Inspiring Modern City of 600 Years of History 044 Mentors Programme at VMU 045 Students’ Union & Lithuanian Student ID Card 090 Virtual Community of Tourists & -

Ost- U. Westpreußen Resources (Including Danzig) at the IGS Library

Ost- u. WestPreußen Resources (including Danzig) at the IGS Library Introduction to East & West Prussia and Danzig The Map Guide to German Parish Registers series has five volumes devoted to this region, #44 through #48. The first two cover West Prussia, with #44 devoted to the Regierungsbezirk Danzig and #45 the RB Marienwerder. The last three are for East Prussia, and deal with RB Allenstein, RB Königsberg and RB Gumbinnen, respectively. A note from Mark F. Rabideau on OW-Preussen-L for 1 June 2015: As for the broader situation regarding Pommern records, I would guess there is a about a 80-90% record loss due to WW2 It is truly bleak. Westpreussen fared somewhat better; the record loss there is more on the order of ~40% across that former region. The bottom line is that the LDS records are most likely your best record source (currently). It may be that archion will eventually provide (in the future) some currently unavailable records (but that is hard to know for certain). See: http://wiki-de.genealogy.net/Archion Region-wide Resources Online Research in former (pre-1945) German lands — http://www.heimat-der-vorfahren.de [O/W] Prussian Antiquarian Society (German) — http://www.prussia-gesellschaft.de Society: Verein für Familienforschung in O/WPr. — http://www.vffow.de/default.htm [To enter the online databases, Login Name = “Gast” & Passwort = “vffow”.] (former) East German Gen. Assoc. (German) — http://www.agoff.de German-Baltic Gen. Soc. (German) — http://www.dbgg.de/index.htm Researching Germans in today’s Poland — http://www.unsere-ahnen.de Forum on former areas — http://forum.ahnenforschung.net/archive/index.php/f-43.html Forum topics organized by Kreis — http://www.deutscheahnen.de/forum/ Placename listings — http://www.schuka.net/FamFo/HG/orte_a.htm http://www.schuka.net/FamFo/HG/Aemter-OWP.htm Placenames, translations from German to present-day Polish — https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liste_deutscher_Bezeichnungen_polnischer_Orte Family names — http://forum.naanoo.com/freeboard/board/index.php?userid=21893 Scots in E. -

Jurgelėnaitė, A., Kriaučiūnienė J., Šarauskienė, D. Spatial And

doi:10.5200/baltica.2012.25.06 BALTICA Volume 25 Number 1 June 2012 : 65–76 Spatial and temporal variation in the water temperature of Lithuanian rivers Aldona Jurgelėnaitė, Jūratė Kriaučiūnienė, Diana Šarauskienė Jurgelėnaitė, A., Kriaučiūnienė, J., Šarauskienė, D., 2012. Spatial and temporal variation in the water temperature of Lithuanian rivers. Baltica, 25(1) 65–76. Vilnius. ISSN 0067–3064. Abstract Water temperature is one of the twelve physico–chemical elements of water quality, used for the as- sessment of the ecological status of surface waters according to the Water Framework Directive (WFD) 2000/60/ EC. The thermal regime of Lithuanian rivers is not sufficiently studied. The presented article describes the temporal and spatial variation of water temperature in Lithuanian rivers. Since a huge amount of statistical data is available (time series from 141 water gauging stations), the average water temperatures of the warm season (May–October) have been selected to analyse because that is the time when the most intensive hydrological and hydro–biological processes in water bodies take place. Spatial distribution of river water temperature is mostly influenced by the type of river feeding, prevalence of sandy soils and lakes in a basin, river size, and orogra- phy of a river basin as well as anthropogenic activity. The temporal distribution of river water temperature is determined by climatic factors and local conditions. The averages of the warm season water temperature for 41 WGS are 15.1°C in 1945–2010, 14.9°C in 1961–1990, and 15.4°C in 1991–2010. The most significant changes in water temperature trends are identified in the period of 1991–2010. -

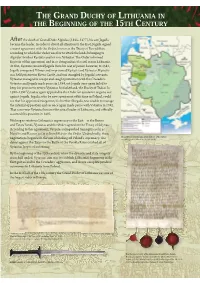

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the Beginning of the 15Th

THE GRAND DUCHY OF LITHUANIA IN THE BEGINNING OF THE 15 TH CENTURY A er the death of Grand Duke Algirdas (1345–1377), his son Jogaila became the leader. In order to divert all a ention to the East, Jogaila signed a secret agreement with the Order, known as the Treaty of Dovydiškės, according to which the Order was free to a ack the lands belonging to Algirdas’ brother Kęstutis and his son, Vytautas. e Order informed Kęstutis of this agreement and in so doing initiated a civil war in Lithuania. At + rst, Kęstutis removed Jogaila from his seat of power, however, in 1382, Jogaila conquered Vilnius and imprisoned Kęstutis and Vytautas. Kęstutis was held prisoner in Krėva Castle, and was strangled by Jogaila’s servants. Vytautas managed to escape and sought protection with the Crusaders. Vytautas and Jogaila made peace in 1384, yet Jogaila once again failed to keep his promise to return Vytautas his fatherland, the Duchy of Trakai. In 1390–1392 Vytautas again appealed to the Order for assistance to go to war against Jogaila. Jogaila, who by now spent most of his time in Poland, could see that his appointed vicegerent, his brother Skirgaila, was unable to manage the internal opposition and so, once again made peace with Vytautas in 1392. at same year Vytautas became the actual leader of Lithuania, and o6 cially assumed this position in 1401. Wishing to reinforce Lithuania’s supremacy in the East – in the Ruzen and Tatars’ lands, Vytautas and the Order agreed on the Treaty of Salynas. According to this agreement, Vytautas relinquished Samogitia as far as Nevėžis and Kaunas as far as Rumšiškės to the Order.