History of the Crusades. Episode 280. the Baltic Crusades. the Samogitian Crusade Part XIII

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EAA Meeting 2016 Vilnius

www.eaavilnius2016.lt PROGRAMME www.eaavilnius2016.lt PROGRAMME Organisers CONTENTS President Words .................................................................................... 5 Welcome Message ................................................................................ 9 Symbol of the Annual Meeting .............................................................. 13 Commitees of EAA Vilnius 2016 ............................................................ 14 Sponsors and Partners European Association of Archaeologists................................................ 15 GENERAL PROGRAMME Opening Ceremony and Welcome Reception ................................. 27 General Programme for the EAA Vilnius 2016 Meeting.................... 30 Annual Membership Business Meeting Agenda ............................. 33 Opening Ceremony of the Archaelogical Exhibition ....................... 35 Special Offers ............................................................................... 36 Excursions Programme ................................................................. 43 Visiting Vilnius ............................................................................... 57 Venue Maps .................................................................................. 64 Exhibition ...................................................................................... 80 Exhibitors ...................................................................................... 82 Poster Presentations and Programme ........................................... -

Archaeological Heritage in Lithuania After the 1990S: Defining, Protecting, Interpreting 161

Archaeological Heritage in Lithuania after the 1990s: Defining, Protecting, Interpreting 161 Archaeological Heritage in Lithuania after the 1990s: Defining, Protecting, Interpreting Justina Poškienė Abstract The paper seeks to present developments in the state system of archaeological heritage protection in Lithu- ania after the 1990s. National legislation was essentially modified twice: in 1994 and in 2004. As- pects of defining (inventarisation, assessment and listing in the national Register of Cultural Properties), protecting (requirements for archaeological heritage protection, regulations on archaeological excavations’ procedures) and the interpreting of archaeological heritage (preservation of archaeological remains in situ) are under consideration. Keywords: archaeological heritage, assessment, archaeological excavations, in situ. Santrauka Straipsnyje pristatomas Lietuvos archeologinis paveldas bei apžvelgiama valstybinė archeologinio paveldo apsaugos sistema po 1990 metų. Teisinis paveldo apsaugos reglamentavimas iš esmės keitėsi 1994 ir 2004 metais. Straipsnyje aptariami šie archeologinio paveldo apsaugos aspektai: apskaita (archeologinio paveldo vertinimas, įrašymas į Kultūros vertybių registrą, archeologinių objektų paveldosauginis statusas), ap- sauga (reikalavimai archeologiniams tyrimams, ardomųjų archeologinių tyrimų apimtys, archeologinių tyrimų kontrolės sistema) ir archeologinio paveldo interpretacija (archeologinio paveldo apsauga in situ). Recent_developments_FINAL.indd 161 9.1.2017 12:41:33 162 Justina Poškienė -

Algirdas Matonis 772 Greenfield Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15217 [email protected] Mobile No: +1 412 961 2559

Algirdas Matonis 772 Greenfield Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15217 [email protected] Mobile No: +1 412 961 2559 Professional Experience 2015 – Present: River City Brass Band Principal Euphonium Player Key Responsibilities • Ensure a successful concert preparation for Euphonium and Baritone section • Playing solo performances with the band • Find substitute players in case of absence of assigned section member • Judge auditions for new players 2016 – Present River City Youth Brass Band Low Brass Instructor Key Responsibilities • Low brass sectional coaching • Full band coaching • Auditioning seat placements for low brass 2018 – Present Duquesne University Mary Pappert School of Music Adjunct Professor of Euphonium Key Responsibilities: • Teach one on one lessons to euphonium students or any other assigned brass students • Teach a studio class for low brass students • Prepare students for jury exams, auditions and end year recitals • Prepare students for ensemble assignments • Grade jury exams and recitals • Recruit new students • Judge euphonium applicant for school of music Education 2010 – 2014 Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester Bachelor in Euphonium Performance 2015 – 2017 Carnegie Mellon University Advanced Music Studies in Euphonium Performance, Orchestral Track Additional Qualifications 2006 “Trakai Fanfare Week”, Lithuania Masterclasses with Steven Mead, Fritz Damrow, Bert Langeler 2007 “Trakai Fanfare Week”, Lithuania Masterclasses with Steven Mead, Fritz Damrow, Bert Langeler, Marius Balcytis 2008 “Trakai Fanfare Week”, -

How to Survive and Not to Get Bored in Kaunas

/ HOW TO SURVIVE AND NOT TO GET BORED IN KAUNAS / 004 DISCOVER VYTAUTAS MAGNUS UNIVERSITY 007_ We Were and Still Are Waiting for You to Come! 009_ Vytautas Magnus University – When? Where? Why? 012_ Facts and Figures About the University Survival guide: 014_ International Office – Ready to Help You How to survive and not to get bored in Kaunas 016 SURVIVAL GUIDE 018_ Arriving 019_ Incoming Student’s To-Do List Before Coming to VMU ? 059 Where to Eat Out and Have a Drink? 020_ Lithuanian Customs & Consular Information 064 Where to Spend Evenings & Nights? 023_ Reaching Kaunas & Travelling ored 068 What Should I Visit in Kaunas? B 026 Studying 072 Places Worth Your Attention @ VMU 2 027_ How to Design the Study Schedule? et 3 G 075 Kaunas for Keen Theatre Goers 028_ System of Credits & Grading @ VMU O 078 Information for Passionate Cinema Goers 030_ Lithuanian Language Courses T 080 Online News in [En] and [Ru] 033_ Library & Its Reading Rooms ot 080 Learn [Lt] is Easy if You Know How 034_ Academic Year – What & When? N 082 Culture Which Surrounds You in Kaunas 036 Living ow 084 Before You Leave 037_ Incoming Student’s To-Do List After Coming to VMU H 085 Incoming Student’s To-Do List Before Leaving VMU 038 Things You Should Know About the Dormitory of VMU 040 Life in a Dormitory – Some Rules, Tips & Tricks ? 042 Health Care and Insurance 086 DISCOVER KAUNAS 089 Inspiring Modern City of 600 Years of History 044 Mentors Programme at VMU 045 Students’ Union & Lithuanian Student ID Card 090 Virtual Community of Tourists & -

The Baltics EU/Schengen Zone Baltic Tourist Map Traveling Between

The Baltics Development Fund Development EU/Schengen Zone Regional European European in your future your in g Investin n Unio European Lithuanian State Department of Tourism under the Ministry of Economy, 2019 Economy, of Ministry the under Tourism of Department State Lithuanian Tampere Investment and Development Agency of Latvia, of Agency Development and Investment Pori © Estonian Tourist Board / Enterprise Estonia, Enterprise / Board Tourist Estonian © FINL AND Vyborg Turku HELSINKI Estonia Latvia Lithuania Gulf of Finland St. Petersburg Estonia is just a little bigger than Denmark, Switzerland or the Latvia is best known for is Art Nouveau. The cultural and historic From Vilnius and its mysterious Baroque longing to Kaunas renowned Netherlands. Culturally, it is located at the crossroads of Northern, heritage of Latvian architecture spans many centuries, from authentic for its modernist buildings, from Trakai dating back to glorious Western and Eastern Europe. The first signs of human habitation in rural homesteads to unique samples of wooden architecture, to medieval Lithuania to the only port city Klaipėda and the Curonian TALLINN Novgorod Estonia trace back for nearly 10,000 years, which means Estonians luxurious palaces and manors, churches, and impressive Art Nouveau Spit – every place of Lithuania stands out for its unique way of Orebro STOCKHOLM Lake Peipus have been living continuously in one area for a longer period than buildings. Capital city Riga alone is home to over 700 buildings built in rendering the colorful nature and history of the country. Rivers and lakes of pure spring waters, forests of countless shades of green, many other nations in Europe. -

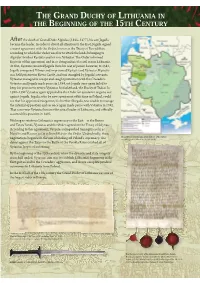

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the Beginning of the 15Th

THE GRAND DUCHY OF LITHUANIA IN THE BEGINNING OF THE 15 TH CENTURY A er the death of Grand Duke Algirdas (1345–1377), his son Jogaila became the leader. In order to divert all a ention to the East, Jogaila signed a secret agreement with the Order, known as the Treaty of Dovydiškės, according to which the Order was free to a ack the lands belonging to Algirdas’ brother Kęstutis and his son, Vytautas. e Order informed Kęstutis of this agreement and in so doing initiated a civil war in Lithuania. At + rst, Kęstutis removed Jogaila from his seat of power, however, in 1382, Jogaila conquered Vilnius and imprisoned Kęstutis and Vytautas. Kęstutis was held prisoner in Krėva Castle, and was strangled by Jogaila’s servants. Vytautas managed to escape and sought protection with the Crusaders. Vytautas and Jogaila made peace in 1384, yet Jogaila once again failed to keep his promise to return Vytautas his fatherland, the Duchy of Trakai. In 1390–1392 Vytautas again appealed to the Order for assistance to go to war against Jogaila. Jogaila, who by now spent most of his time in Poland, could see that his appointed vicegerent, his brother Skirgaila, was unable to manage the internal opposition and so, once again made peace with Vytautas in 1392. at same year Vytautas became the actual leader of Lithuania, and o6 cially assumed this position in 1401. Wishing to reinforce Lithuania’s supremacy in the East – in the Ruzen and Tatars’ lands, Vytautas and the Order agreed on the Treaty of Salynas. According to this agreement, Vytautas relinquished Samogitia as far as Nevėžis and Kaunas as far as Rumšiškės to the Order. -

Dark Times: Art and Artists of Vilnius in 1939–1941

326 Dark Times: Art and Artists of Vilnius in 1939–1941 Giedrė Jankevičiūtė Vilnius Academy of Arts Maironio St. 6, LT-01124 Vilnius e-mail: [email protected] The aim of this paper is to discuss and reconstruct in general fe- atures the reality of the Vilnius artistic community from late autumn 1939 to June 1941. This period of less than two years significantly changed the configuration of the artistic community of the city, the system of institutions shaping the art scene as well as the artistic goals. It also brought forth new names and inspired new images. These changes were above all determined by political circumstances: the war that broke out in Poland on 1 September 1939; the ceding of Vilnius and the Vilnius region to Lithuania; two Soviet occupations: in the autumn of 1939 and June 1940, and the subsequent Nazi occupation a year later. The influence of politics on the art scene and the life of artists has been explored in institutional and other aspects by both Lithuanian and Polish art historians, but the big picture is not yet complete, and the general narrative is still under construction. A further aim of this paper is to highlight some elements that have not received sufficient atten- tion in historiography and that are necessary for the reconstruction of the whole. Some facts of cooperation or its absence among artists of various ethnicities are presented, and the question is raised on the extent to which these different groups were affected by Sovietisation, and what impact this fragmentation had on the city’s art scene. -

Gidas EN.Pdf

MAP OF THE LEFT AND RIGHT BANKS OF NEMUNAS 1 Kaunas Cathedral 8 Gelgaudiškis 2 Kaunas Vytautas Magnus Church 9 Kiduliai 3 Raudondvaris 10 Kulautuva 4 Kačerginė 11 Paštuva 5 Zapyškis 12 Vilkija 6 Ilguva 14 Seredžius 7 Plokščiai 15 Veliuona 1 2 3 THE ROAD OF THE SAMOGITIAN BAPTISM A GUIDE FOR PILGRIMS AND TRAVELERS LITHUANIAN CATHOLIC AcADEMY OF SCIENCE, 2013 4 5 UDK 23/28(474.5)(091)(036) CONTENTS Ro-01 Funded by the State according Presenting Guide to the Pilgrimage of the Baptism to the Programme for Commemoration of the Baptism of Samogitia of Samogitia to the Hearts and Hands of Dear and the Founding of the Samogitian Diocese 2009-2017 Readers Foreword by the Bishop of Telšiai 7 The project is partly funded Kaunas Cathedral 15 by THE FOUNDATION FOR THE SUPPORT OF CULTURE Kaunas Vytautas Magnus Church 20 Raudondvaris 23 Kačerginė 27 Zapyškis 30 Texts by mons. RImantas Gudlinkis and Vladas LIePUoNIUS Ilguva 33 Project manager and Special editor Vytautas Ališauskas Plokščiai 36 Assistant editor GIeDRė oLSeVIčIūTė Gelgaudiškis 39 Translator JUSTINAS ŠULIoKAS Kiduliai 42 editor GABRIeLė GAILIūTė Kulautuva 45 Layout by VIoLeta BoSKAITė Paštuva 47 Photographs by Vytautas RAzmA, KeRNIUS PAULIUKoNIS, Vilkija 50 TOMAS PILIPONIS, Arrest Site of Priest Antanas Mackevičius 52 also by ARūNAS BaltėNAS (p. 119), VIoLeTA BoSKAITė (front cover, Seredžius 54 p. – 105, 109 top, 112 top, 113 bottom, 114, 125, 128, 129, 130, 133 bottom, 134 top, 141), Klaudijus Driskius (p. 85 bottom), Veliuona 57 PAULIUS SPūDyS (p. 48 bottom), AntanAS ŠNeIDeRIS (p. 37), Gėluva. Birutkalnis 60 SigitAS VarnAS (p. -

The Lithuanian Nobility in the Late- Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries: Composition and Structure

LITHUANIAN HISTORICAL STUDIES 7 2002 ISSN 1392-2343 pp. 1–22 THE LITHUANIAN NOBILITY IN THE LATE- FOURTEENTH AND FIFTEENTH CENTURIES: COMPOSITION AND STRUCTURE RIMVYDAS PETRAUSKAS ABSTRACT This paper presents a critical review of the historiographically dominant theory stating that the upper layer of the Lithuanian nobility formed its independent power only around the middle of the fifteenth century. The extant sources shed little light on the role of the nobility in the political processes of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. A complex of sources, more fully reflecting the specifics of the country, appeared only after the arrival of writing in Lithuania at the end of the fourteenth century. It was only in this period that the place of the nobles in the system of government became evident. Therefore, it is possible to speak about a distorted perspective, suggested by the early records. The paper presents a definition of the nobility and an analysis of the origin, composition and structure of the Lithuanian ruling élite in the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Consequently it is possible to speak about the prerequisites of the rule of this social group and the duality of the power of the grand duke and the nobility. Two principal tendencies of the development of the Lithuanian nobility in the fifteenth century – personal continuity and internal transformation (family structure) – are distinguished. In Lithuanian historical models the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries have acquired the image of the epoch of ‘ducal Lithuania’. This was a period of the rule of the grand dukes Gediminas, Algirdas, Kęstutis, Jogaila and Vytautas. -

History of the Crusades. Episode 290. the Baltic Crusades. the Samogitian Crusade Part XXII

History of the Crusades. Episode 290. The Baltic Crusades. The Samogitian Crusade Part XXII. Grand Master Konrad von Wallenrode. Hello again. Last week we followed the Crusaders on campaign to Lithuania, where the Crusaders attacked the Lithuanian town of Vilnius with the ultimate aim of securing the town, defeating Jogaila and Skirgaila, and elevating their man Vytautas to the position of ruler of Lithuania. None of these events came to pass, but it did result in one crusader, Henry Bolingbroke, the future King of England, drinking a lot of beer with his men. We also saw last week the death of Grand Master Konrad Zollner von Rothenstein and his replacement by another Konrad: Konrad von Wallenrode. Now, William Urban points out in his book "The Samogitian Crusade" that, as the current Grand Commander of the Teutonic Order, Konrad von Wallenrode was the obvious standout candidate to be elected as the next Grand Master. The Wallenrode family had played prominent roles inside the Teutonic Order for some time, and Konrad von Wallenrode had enjoyed success as Grand Commander. Despite this though, there were apparently significant misgivings inside the Teutonic Order about the appointment of Konrad von Wallenrode are to the position of Grand Master. Why? Well, because Konrad von Wallenrode was a military man, through and through. In fact, to say that Konrad von Wallenrode had little or no interest in religion wasn't too much of an exaggeration, and William Urban reports that Konrad took so little notice of priests and God that he was once accused of heresy. The worst fears of the religious men of the Order seemed to have been realised when, after being elected as Grand Master, one of Konrad von Wallenrode first acts was to reform the command structure inside the Order to increase his authority. -

![ALGIRDAS (Olgierd), Grand Duke of Lithuania (1345-77), Son of \Gedin\Inas, Father of \]Ogaua and '[^Vitrigaila](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4655/algirdas-olgierd-grand-duke-of-lithuania-1345-77-son-of-gedin-inas-father-of-ogaua-and-vitrigaila-2474655.webp)

ALGIRDAS (Olgierd), Grand Duke of Lithuania (1345-77), Son of \Gedin\Inas, Father of \]Ogaua and '[^Vitrigaila

PRIESTS. BISHOPS. 15 DUKES; ALGIRDAS (Olgierd), Grand Duke of Lithuania (1345-77), son of \Gedin\inas, father of \]ogaUa and '[^vitrigaila. He shared power with his brother Kfstutis: Vilnius and the eastern part of the country was Algirdas' domain, and Kfstutis reigned in Trakai, Samogitia and other western regions. Thus Algirdas was more concerned about relations with Russian duchies, while Kfstutis dealt with the Teutonic Order. Having lived an adventurous life, Kfstutis, a zealous supporter of pagan Lithuania, called "a heathen knight", enjoyed greater popularity than his brother. However, Algirdas was a more outstanding politician, thus in Algirdas' lifetime Kfstutis occupied only second place in the state. Q I: CtAlO It is known that in the year of Gediminas' death, Algirdas ruled Vitebsk and Krevo. His two wives - princess Maria of Vitebsk and prin• Grand Duke Algirdas of cess \luUanua of Tver - were Russian Orthodox. The majority of his Lilhuania. Artist J. Ozifblowski children adhered to the Russian Orthodox faith, but those who were born in Vilnius remained pagan, like their father. Algirdas annexed Kiev and many other Eastern Slavonic regions to Lithuania, waged war against the Grand Duke of Moscow Dmitry Donskoi and marched as far as the Kremlin. He founded an independ• ent Lithuanian Orthodox metropoly with the centre in Kiev. He defeated the Tartars at the Battle of Blue Waters (1363), participated in the strug• gle against the Teutonic knights with a demand to cede to Lithuania almost all of the ancient Prussian lands along with Konigsberg and a large part of Livonia. In Algirdas' times Lithuania became the largest and most likely strongest Central Eastern European power. -

Utopias and Dystopias All Sessio

CES Virtual 27th International Conference of Europeanists Europe’s Past, Present, and Future: Utopias and Dystopias All sessions are listed in Eastern Daylight Time (EDT). June 2, 2021 1 Pre-Conference Side Events MONDAY, JUNE 14 Networking with Breakout Sessions (private event for fellows) 6/14/2021 10:00 AM to 11:30 AM EDT Mandatory for all dissertation completion and pre-dissertation fellows Through the Science Lens: New Approaches in the Humanities 6/14/2021 1:00 PM to 2:30 PM Mandatory for all dissertation completion and pre-dissertation fellows Moderator: Nicole Shea, CES/Columbia University Speakers: Dominic Boyer - Rice University Arden Hegele - Columbia University Jennifer Edmond - Trinity College Territorial Politics and Federalism Research Network Business Meeting 6/14/2021 1:00 PM to 2:30 PM Business Meeting Chair: Willem Maas - York University TUESDAY, JUNE 15 Mellon-CES Keynote Discussion: Crises of Democracy 6/15/2021 10:00 AM to 11:30 PM Keynote Sponsored by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Mandatory for all dissertation completion and pre-dissertation fellows Chair: Nicole Shea – Director, Council for European Studies Speakers: Eileen Gillooly - Executive Director, Heyman Center for the Humanities, Columbia University Jane Ohlmeyer - Professor of History at Trinity College and Chair of the Irish Research Council 2 European Integration and Political Economy Research Network Speed Mentoring Event 6/15/2021 10:30 AM to 2:30 PM Networking Event Chair: Dermot Hodson - Birkbeck, University of London Knowledge Production and