The Annexation of the Baltic States and Its Effect on the Development of Law Prohibiting Forcible Seizure of Territory William J.H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Legal-Status-Of-East-Jerusalem.Pdf

December 2013 Written by: Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel Cover photo: Bab al-Asbat (The Lion’s Gate) and the Old City of Jerusalem. (Photo by: JC Tordai, 2010) This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or the official opinion of the European Union. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non- governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. The author wishes to thank Adv. Emily Schaeffer for her insightful comments during the preparation of this study. 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 2. Background ............................................................................................................................ 6 3. Israeli Legislation Following the 1967 Occupation ............................................................ 8 3.1 Applying the Israeli law, jurisdiction and administration to East Jerusalem .................... 8 3.2 The Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel ................................................................... 10 4. The Status -

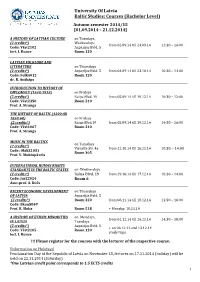

University of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level)

University Of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level) Autumn semester 2014/15 [01.09.2014 – 21.12.2014] A HISTORY OF LATVIAN CULTURE on Tuesdays, (2 credits*) Wednesdays from 02.09.14 till 24.09.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst2102 Azpazijas Bvld. 5 lect. I. Runce Room 120 LATVIAN FOLKLORE AND LITERATURE on Thursdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. 5 from 04.09.14 till 23.10.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: Folk4012 Room 120 dr. R. Auškāps INTRODUCTION TO HISTORY OF DIPLOMACY (1648-1918) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 10:30 – 12:00 Code: Vēst2350 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga THE HISTORY OF BALTIC (1200 till 1850-60) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd.19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 14:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst1067 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga MUSIC IN THE BALTICS on Tuesdays (2 credits*) Visvalža Str. 4a from 21.10.14 till 16.12.14 10:30. – 14:00 Code : MākZ1031 Room 305 Prof. V. Muktupāvels INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARTS IN THE BALTIC STATES on Wednesdays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 29.10.14 till 17.12.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: JurZ2024 Room 6 Asoc.prof. A. Kučs RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT on Thursdays OF LATVIA Azpazijas Bvld. 5 (2 credits*) Room 320 from 06.11.14 till 18.12.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Ekon5069 Prof. B. Sloka Room 518 + Monday, 10.11.14 A HISTORY OF ETHNIC MINORITIES on Mondays, from 01.12.14 till 16.12.14 14:30 – 18:00 IN LATVIA Tuesdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. -

Helsinki Watch Committees in the Soviet Republics: Implications For

FINAL REPORT T O NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE : HELSINKI WATCH COMMITTEES IN THE SOVIET REPUBLICS : IMPLICATIONS FOR THE SOVIET NATIONALITY QUESTIO N AUTHORS : Yaroslav Bilinsky Tönu Parming CONTRACTOR : University of Delawar e PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATORS : Yaroslav Bilinsky, Project Director an d Co-Principal Investigato r Tönu Parming, Co-Principal Investigato r COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 621- 9 The work leading to this report was supported in whole or in part fro m funds provided by the National Council for Soviet and East European Research . NOTICE OF INTENTION TO APPLY FOR COPYRIGH T This work has been requested for manuscrip t review for publication . It is not to be quote d without express written permission by the authors , who hereby reserve all the rights herein . Th e contractual exception to this is as follows : The [US] Government will have th e right to publish or release Fina l Reports, but only in same forma t in which such Final Reports ar e delivered to it by the Council . Th e Government will not have the righ t to authorize others to publish suc h Final Reports without the consent o f the authors, and the individua l researchers will have the right t o apply for and obtain copyright o n any work products which may b e derived from work funded by th e Council under this Contract . ii EXEC 1 Overall Executive Summary HELSINKI WATCH COMMITTEES IN THE SOVIET REPUBLICS : IMPLICATIONS FOR THE SOVIET NATIONALITY QUESTION by Yaroslav Bilinsky, University of Delawar e d Tönu Parming, University of Marylan August 1, 1975, after more than two years of intensive negotiations, 35 Head s of Governments--President Ford of the United States, Prime Minister Trudeau of Canada , Secretary-General Brezhnev of the USSR, and the Chief Executives of 32 othe r European States--signed the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperatio n in Europe (CSCE) . -

2020-Commencement-Program.Pdf

One Hundred and Sixty-Second Annual Commencement JUNE 19, 2020 One Hundred and Sixty-Second Annual Commencement 11 A.M. CDT, FRIDAY, JUNE 19, 2020 2982_STUDAFF_CommencementProgram_2020_FRONT.indd 1 6/12/20 12:14 PM UNIVERSITY SEAL AND MOTTO Soon after Northwestern University was founded, its Board of Trustees adopted an official corporate seal. This seal, approved on June 26, 1856, consisted of an open book surrounded by rays of light and circled by the words North western University, Evanston, Illinois. Thirty years later Daniel Bonbright, professor of Latin and a member of Northwestern’s original faculty, redesigned the seal, Whatsoever things are true, retaining the book and light rays and adding two quotations. whatsoever things are honest, On the pages of the open book he placed a Greek quotation from the Gospel of John, chapter 1, verse 14, translating to The Word . whatsoever things are just, full of grace and truth. Circling the book are the first three whatsoever things are pure, words, in Latin, of the University motto: Quaecumque sunt vera whatsoever things are lovely, (What soever things are true). The outer border of the seal carries the name of the University and the date of its founding. This seal, whatsoever things are of good report; which remains Northwestern’s official signature, was approved by if there be any virtue, the Board of Trustees on December 5, 1890. and if there be any praise, The full text of the University motto, adopted on June 17, 1890, is think on these things. from the Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Philippians, chapter 4, verse 8 (King James Version). -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

Vichy France and the Jews

VICHY FRANCE AND THE JEWS MICHAEL R. MARRUS AND ROBERT 0. PAXTON Originally published as Vichy et les juifs by Calmann-Levy 1981 Basic Books, Inc., Publishers New York Contents Introduction Chapter 1 / First Steps Chapter 2 / The Roots o f Vichy Antisemitism Traditional Images of the Jews 27 Second Wave: The Crises of the 1930s and the Revival of Antisemitism 34 The Reach of Antisemitism: How Influential Was It? 45 The Administrative Response 54 The Refugee Crisis, 1938-41 58 Chapter 3 / The Strategy o f Xavier Vallat, i 9 4 !-4 2 The Beginnings of German Pressure 77 Vichy Defines the Jewish Issue, 1941 83 Vallat: An Activist at Work 96 The Emigration Deadlock 112 Vallat’s Fall 115 Chapter 4 / The System at Work, 1040-42 The CGQJ and Other State Agencies: Rivalries and Border Disputes 128 Business as Usual 144 Aryanization 152 Emigration 161 The Camps 165 Chapter 5 / Public Opinion, 1040-42 The Climax of Popular Antisemitism 181 The DistriBution of Popular Antisemitism 186 A Special Case: Algeria 191 The Churches and the Jews 197 X C ontents The Opposition 203 An Indifferent Majority 209 Chapter 6 / The Turning Point: Summer 1Q42 215 New Men, New Measures 218 The Final Solution 220 Laval and the Final Solution 228 The Effort to Segregate: The Jewish Star 234 Preparing the Deportation 241 The Vel d’Hiv Roundup 250 Drancy 252 Roundups in the Unoccupied Zone 255 The Massacre of the Innocents 263 The Turn in PuBlic Opinion 270 Chapter 7 / The Darquier Period, 1942-44 281 Darquier’s CGQJ and Its Place in the Regime 286 Darquier’s CGQJ in Action 294 Total Occupation and the Resumption of Deportations 302 Vichy, the ABBé Catry, and the Massada Zionists 310 The Italian Interlude 315 Denaturalization, August 1943: Laval’s Refusal 321 Last Days 329 Chapter 8 / Conclusions: The Holocaust in France . -

Importance of European Remembrance for the Future of Europe

European Parliament 2019-2024 TEXTS ADOPTED P9_TA(2019)0021 Importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe European Parliament resolution of 19 September 2019 on the importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe (2019/2819(RSP)) The European Parliament, – having regard to the universal principles of human rights and the fundamental principles of the European Union as a community based on common values, – having regard to the statement issued on 22 August 2019 by First Vice-President Timmermans and Commissioner Jourová ahead of the Europe-Wide Day of Remembrance for the victims of all totalitarian and authoritarian regimes, – having regard to the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted on 10 December 1948, – having regard to its resolution of 12 May 2005 on the 60th anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe on 8 May 19451, – having regard to Resolution 1481 of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe of 26 January 2006 on the need for international condemnation of crimes of totalitarian Communist regimes, – having regard to Council Framework Decision 2008/913/JHA of 28 November 2008 on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia by means of criminal law2, – having regard to the Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism adopted on 3 June 2008, – having regard to its declaration on the proclamation of 23 August as European Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Stalinism and Nazism adopted on 23 September 20083, 1 OJ C 92 E, 20.4.2006, p. 392. 2 OJ L 328, 6.12.2008, p. -

Algirdas Matonis 772 Greenfield Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15217 [email protected] Mobile No: +1 412 961 2559

Algirdas Matonis 772 Greenfield Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15217 [email protected] Mobile No: +1 412 961 2559 Professional Experience 2015 – Present: River City Brass Band Principal Euphonium Player Key Responsibilities • Ensure a successful concert preparation for Euphonium and Baritone section • Playing solo performances with the band • Find substitute players in case of absence of assigned section member • Judge auditions for new players 2016 – Present River City Youth Brass Band Low Brass Instructor Key Responsibilities • Low brass sectional coaching • Full band coaching • Auditioning seat placements for low brass 2018 – Present Duquesne University Mary Pappert School of Music Adjunct Professor of Euphonium Key Responsibilities: • Teach one on one lessons to euphonium students or any other assigned brass students • Teach a studio class for low brass students • Prepare students for jury exams, auditions and end year recitals • Prepare students for ensemble assignments • Grade jury exams and recitals • Recruit new students • Judge euphonium applicant for school of music Education 2010 – 2014 Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester Bachelor in Euphonium Performance 2015 – 2017 Carnegie Mellon University Advanced Music Studies in Euphonium Performance, Orchestral Track Additional Qualifications 2006 “Trakai Fanfare Week”, Lithuania Masterclasses with Steven Mead, Fritz Damrow, Bert Langeler 2007 “Trakai Fanfare Week”, Lithuania Masterclasses with Steven Mead, Fritz Damrow, Bert Langeler, Marius Balcytis 2008 “Trakai Fanfare Week”, -

Nurses and Midwives in Nazi Germany

Downloaded by [New York University] at 03:18 04 October 2016 Nurses and Midwives in Nazi Germany This book is about the ethics of nursing and midwifery, and how these were abrogated during the Nazi era. Nurses and midwives actively killed their patients, many of whom were disabled children and infants and patients with mental (and other) illnesses or intellectual disabilities. The book gives the facts as well as theoretical perspectives as a lens through which these crimes can be viewed. It also provides a way to teach this history to nursing and midwifery students, and, for the first time, explains the role of one of the world’s most historically prominent midwifery leaders in the Nazi crimes. Downloaded by [New York University] at 03:18 04 October 2016 Susan Benedict is Professor of Nursing, Director of Global Health, and Co- Director of the Campus-Wide Ethics Program at the University of Texas Health Science Center School of Nursing in Houston. Linda Shields is Professor of Nursing—Tropical Health at James Cook Uni- versity, Townsville, Queensland, and Honorary Professor, School of Medi- cine, The University of Queensland. Routledge Studies in Modern European History 1 Facing Fascism 9 The Russian Revolution of 1905 The Conservative Party and the Centenary Perspectives European dictators 1935–1940 Edited by Anthony Heywood and Nick Crowson Jonathan D. Smele 2 French Foreign and Defence 10 Weimar Cities Policy, 1918–1940 The Challenge of Urban The Decline and Fall of a Great Modernity in Germany Power John Bingham Edited by Robert Boyce 11 The Nazi Party and the German 3 Britain and the Problem of Foreign Office International Disarmament Hans-Adolf Jacobsen and Arthur 1919–1934 L. -

History of the Crusades. Episode 280. the Baltic Crusades. the Samogitian Crusade Part XIII

History of the Crusades. Episode 280. The Baltic Crusades. The Samogitian Crusade Part XIII. The Siege of Kaunas 1362. Hello again. Last week, we saw an effort by the Archbishop of Prague to convert the Lithuanian leaders to Christianity fail spectacularly, with the two pagan brothers making outrageous demands in return for their baptism, then laughing at and mocking the delegation when they objected. The upshot of this event was that converting the Lithuanians to Christianity by peaceful means was now permanently off the table as a goal to be pursued, so the only option left on the table was to convert the pagans by force. The Teutonic Order then spent time and effort constructing a bunch of new castles in Samogitia, which would provide a larger, more permanent Latin Christian presence in the region. Then, in the spring of the year 1362, fighting men from across Prussia, along with crusaders from Germany, Italy and England, gathered in Prussia, ready to head to Samogitia. This was to be a major Crusading expedition. William Urban describes it in his book "The Samogitian Crusade" as being a, and I quote, "huge force" end quote. Now you will notice that the Crusaders are departing in spring, not winter. That's because they don't need to ride across frozen rivers and swamps to get to Samogitia. Why don't they need to ride across frozen rivers and swamps to get to Samogitia? Well, because they are sailing there. Yes, in a novel break from tradition, the Grand Master and the Marshall of the Teutonic forces have come up with a plan to get everyone on board ships. -

Publications

Year Journal Volume Page Title PMID Authors Rapid non-uniform adaptation to Xue, Jenny Y; Zhao, Yulei; Aronowitz, Jordan; Mai, Trang T; Vides, Alberto; conformation-specific KRAS(G12C) Qeriqi, Besnik; Kim, Dongsung; Li, Chuanchuan; de Stanchina, Elisa; Mazutis, 2020 Nature 577 421-425 inhibition. 31915379 Linas; Risso, Davide; Lito, Piro Amor, Corina; Feucht, Judith; Leibold, Josef; Ho, Yu-Jui; Zhu, Changyu; Alonso- Curbelo, Direna; Mansilla-Soto, Jorge; Boyer, Jacob A; Li, Xiang; Giavridis, Theodoros; Kulick, Amanda; Houlihan, Shauna; Peerschke, Ellinor; Friedman, Senolytic CAR T cells reverse Scott L; Ponomarev, Vladimir; Piersigilli, Alessandra; Sadelain, Michel; Lowe, 2020 Nature 583 127-132 senescence-associated pathologies. 32555459 Scott W Ruscetti, Marcus; Morris 4th, John P; Mezzadra, Riccardo; Russell, James; Leibold, Josef; Romesser, Paul B; Simon, Janelle; Kulick, Amanda; Ho, Yu-Jui; Senescence-Induced Vascular Fennell, Myles; Li, Jinyang; Norgard, Robert J; Wilkinson, John E; Alonso- Remodeling Creates Therapeutic Curbelo, Direna; Sridharan, Ramya; Heller, Daniel A; de Stanchina, Elisa; 2020 Cell 181 424-441.e21 Vulnerabilities in Pancreas Cancer. 32234521 Stanger, Ben Z; Sherr, Charles J; Lowe, Scott W Uckelmann, Hannah J; Kim, Stephanie M; Wong, Eric M; Hatton, Charles; Therapeutic targeting of preleukemia Giovinazzo, Hugh; Gadrey, Jayant Y; Krivtsov, Andrei V; Rücker, Frank G; cells in a mouse model of NPM1 Döhner, Konstanze; McGeehan, Gerard M; Levine, Ross L; Bullinger, Lars; 2020 Science (New York, N.Y.) 367 586-590 mutant acute myeloid leukemia. 32001657 Vassiliou, George S; Armstrong, Scott A Ganesh, Karuna; Basnet, Harihar; Kaygusuz, Yasemin; Laughney, Ashley M; He, Lan; Sharma, Roshan; O'Rourke, Kevin P; Reuter, Vincent P; Huang, Yun-Han; L1CAM defines the regenerative origin Turkekul, Mesruh; Emrah, Ekrem; Masilionis, Ignas; Manova-Todorova, Katia; of metastasis-initiating cells in Weiser, Martin R; Saltz, Leonard B; Garcia-Aguilar, Julio; Koche, Richard; Lowe, 2020 Nature cancer 1 28-45 colorectal cancer. -

Human Rights and History a Challenge for Education

edited by Rainer Huhle HUMAN RIGHTS AND HISTORY A CHALLENGE FOR EDUCATION edited by Rainer Huhle H UMAN The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Genocide Convention of 1948 were promulgated as an unequivocal R response to the crimes committed under National Socialism. Human rights thus served as a universal response to concrete IGHTS historical experiences of injustice, which remains valid to the present day. As such, the Universal Declaration and the Genocide Convention serve as a key link between human rights education and historical learning. AND This volume elucidates the debates surrounding the historical development of human rights after 1945. The authors exam- H ine a number of specific human rights, including the prohibition of discrimination, freedom of opinion, the right to asylum ISTORY and the prohibition of slavery and forced labor, to consider how different historical experiences and legal traditions shaped their formulation. Through the examples of Latin America and the former Soviet Union, they explore the connections · A CHALLENGE FOR EDUCATION between human rights movements and human rights education. Finally, they address current challenges in human rights education to elucidate the role of historical experience in education. ISBN-13: 978-3-9810631-9-6 © Foundation “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future” Stiftung “Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft” Lindenstraße 20–25 10969 Berlin Germany Tel +49 (0) 30 25 92 97- 0 Fax +49 (0) 30 25 92 -11 [email protected] www.stiftung-evz.de Editor: Rainer Huhle Translation and Revision: Patricia Szobar Coordination: Christa Meyer Proofreading: Julia Brooks and Steffi Arendsee Typesetting and Design: dakato…design. David Sernau Printing: FATA Morgana Verlag ISBN-13: 978-3-9810631-9-6 Berlin, February 2010 Photo Credits: Cover page, left: Stèphane Hessel at the conference “Rights, that make us Human Beings” in Nuremberg, November 2008.