Thesis Hum 2021 Aranha Mark.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Synonym to Conservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage: Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture, Heading for Its 30Th Anniversary

A Synonym to Conservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage: Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture, Heading for Its 30th Anniversary V. Jayarajan Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture Folkland, International Centre for Folklore and Culture is an institution that was first registered on December 20, 1989 under the Societies Registration Act of 1860, vide No. 406/89. Over the last 16 years, it has passed through various stages of growth, especially in the fields of performance, production, documentation, and research, besides the preservation of folk art and culture. Since its inception in 1989, Folkland has passed through various phases of growth into a cultural organization with a global presence. As stated above, Folkland has delved deep into the fields of stage performance, production, documentation, and research, besides the preservation of folk art and culture. It has strived hard and treads the untrodden path with a clear motto of preservation and inculcation of old folk and cultural values in our society. Folkland has a veritable collection of folk songs, folk art forms, riddles, fables, myths, etc. that are on the verge of extinction. This collection has been recorded and archived well for scholastic endeavors and posterity. As such, Folkland defines itself as follows: 1. An international center for folklore and culture. 2. A cultural organization with clearly defined objectives and targets for research and the promotion of folk arts. Folkland has branched out and reached far and wide into almost every nook and corner of the world. The center has been credited with organizing many a festival on folk arts or workshop on folklore, culture, linguistics, etc. -

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

People's Perceptıon Regardıng Jırga in Pakhtun Socıety

J. Appl. Environ. Biol. Sci. , 8(1)180-183, 2018 ISSN: 2090-4274 Journal of Applied Environmental © 2018, TextRoad Publication and Biological Sciences www.textroad.com People’s Perceptıon Regardıng Jırga ın Pakhtun Socıety Muhammad Nisar* 1, Anas Baryal 1, Dilkash Sapna 1, Zia Ur Rahman 2 Department of Sociology and Gender Studies, Bacha Khan University, Charsadda, KP, Pakistan 1 Department of Computer Science, Bacha Khan University, Charsadda, KP, Pakistan 2 Received: September 21, 2017 Accepted: December 11, 2017 ABSTRACT “This paper examines the institution of Jirga, and to assess the perceptions of the people regarding Jirga in District Malakand Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. A sample of 12 respondents was taken through convenience sampling method. In-depth interview was used as a tool for the collection of data from the respondents. The results show that Jirga is deep rooted in Pashtun society. People cannot go to courts for the solution of every problem and put their issues before Jirga. Jirga in these days is not a free institution and cannot enjoy its power as it used to be in the past. The majorities of Jirgaees (Jirga members) are illiterate, cannot probe the cases well, cannot enjoy their free status as well as take bribes and give their decisions in favour of wealthy or influential party. The decisions of Jirgas are not fully based on justice, as in many cases it violates the human rights. Most disadvantageous people like women and minorities are not given representation in Jirga. The modern days legal justice system or courts are exerting pressure on Jirga and declare it as illegal. -

Power Politics in Kolathunadu (1663-1697)

The Ali Rajas of Cannanore: status and identity at the interface of commercial and political expansion, 1663-1723 Mailaparambil, J.B. Citation Mailaparambil, J. B. (2007, December 12). The Ali Rajas of Cannanore: status and identity at the interface of commercial and political expansion, 1663-1723. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12488 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12488 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). CHAPTER SIX POWER POLITICS IN KOLATHUNADU (1663-1697) In the month of October 1690, three Dutch soldiers deserted from the Dutch fortress in Cannanore and were caught by the Nayars of the Kolathiri prince, Keppoe Unnithamburan, in Maday—a place some twenty kilometres to the north of Cannanore.1 Although they tried to hide their real identity by claiming first that they were English and later Portuguese, the Nayars who were sent by the Company to track them successfully exposed their pretensions. Realizing the graveness of the situation, the soldiers desperately pleaded with the Prince not to extradite them to the Company for fear of capital punishment. Moved by their pathetic imploring, the Prince took them under his protection and ordered the Company Nayars to turn back, stating that he would take them to Cannanore personally, which, in fact, did not happen. The Company servants complained about this incident to the Ali Raja. The latter assured them he would settle the issue by promising to advise and caution the inexperienced young prince regarding this issue. -

UUKMA-Kalamela-E-Manual-2017

ഉള്ളടക്കം INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................2 AIM .......................................................................................................................................................................2 Eligibility for participation ....................................................................................................................................2 age Categories ......................................................................................................................................................2 Age proof ..............................................................................................................................................................2 List of ITEMS .........................................................................................................................................................3 Number of PARTICIPATING Items .........................................................................................................................3 Number of entries for Regional Kalamela ........................................................................................................3 Number of entries for National Kalamela: .......................................................................................................3 GENERAL GUIDE LINES ..........................................................................................................................................3 -

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT History Ponnani Is Popularly Known As “The Mecca of Kerala”

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT HISTORY Ponnani is popularly known as “the Mecca of Kerala”. As an ancient harbour city, it was a major trading hub in the Malabar region, the northernmost end of the state. There are many tales that try to explain how the place got its name. According to one, the prominent Brahmin family of Azhvancherry Thambrakkal once held sway over the land. During their heydays, they offered ponnu aana [elephants made of gold] to the temples, and this gave the land the name “Ponnani”. According to another, due to trade, ponnu [gold] from the Arab lands reached India for the first time at this place, and thus caused it to be named “Ponnani”. It is believed that a place that is referred to as “Tyndis” in the Greek book titled Periplus of the Erythraean Sea is Ponnani. However historians have not been able to establish the exact location of Tyndis beyond doubt. Nor has any archaeological evidence been recovered to confirm this belief. Politically too, Ponnani had great importance in the past. The Zamorins (rulers of Calicut) considered Ponnani as their second headquarters. When Tipu Sultan invaded Kerala in 1766, Ponnani was annexed to the Mysore kingdom. Later when the British colonized the land, Ponnani came under the Bombay Province for a brief interval of time. Still later, it was annexed Malabar and was considered part of the Madras Province for one-and-a-half centuries. Until 1861, Ponnani was the headquarters of Koottanad taluk, and with the formation of the state of Kerala in 1956, it became a taluk in Palakkad district. -

A Note on the Genitive Particle Ħaqq in Yemeni Arabic Free Genitives Mohammed Ali Qarabesh, University of Albayda Mohammed Q

A note on ħaqq in Yemeni Arabic … Qarabesh & Shormani A Note on the Genitive particle ħaqq in Yemeni Arabic Free Genitives Mohammed Ali Qarabesh, University of Albayda Mohammed Q. Shormani, University of Ibb الملخص: تتىاوه هذي اىىرقح ميمح "حق" فٍ اىيهجح اىُمىُح ورتثتها اىىحىَح فٍ تزمُة إضافح اىمينُح اىتحيُيُح، وتقذً ىها تحيُو وحىٌ وصفٍ، حُث َفتزض اىثاحثان أن هىاك وىػُه مه هذي اىنيمح فٍ اىيهجح اىُمىُح: ا( تيل اىتٍ ﻻ تظهز ػيُها ػﻻماخ اىتطاتق، مثو "اىسُاراخ حق ػيٍ"، حُث وزي أن ميمح "اىسُاراخ" ىها اىسماخ )جمغ، مؤوث، غائة( وىنه ميمح "حق" ﻻ تتطاتق مؼها فٍ أٌ مه هذي اىصفاخ، و ب( تيل اىتٍ تظهز ػيُها ػﻻماخ اىتطاتق مثو "اىسُاراخ حقاخ ػيٍ" حُث تتطاتق اىنيمتان "اىسُاراخ" و"حقاخ" فٍ مو اىسماخ. وؼَزض اىثاحثان أن اىىىع اﻷوه َ ستخذً فٍ مىاطق مثو صىؼاء، ػذن، إب... اىخ، واىثاوٍ فٍ شثىج وحضزمىخ ... اىخ. وَخيص اىثاحثان إىً أن هىاك دىُو ػميٍ ىُس فقظ ػيً وجىد اىىحى اىنيٍ فٍ "اىمينح اىيغىَح" تو أَضا ػيً "تَ ْى َس َطح" هذا اىىحى، ىُس فقظ تُه اىيغاخ تو وتُه ىهجاخ اىيغح اىىاحذج. الكلمات المفتاحية: اىيغاخ اىسامُح، اىؼزتُح اىُمىُح، اىؼثزَح، اى م ْينُح، "حق" Abstract This paper provides a descriptive syntactic analysis of ħaqq in Yemeni Arabic (YA). ħaqq is a Semitic Free Genitive (FG) particle, much like the English of. A FG minimally consists of a head N, genitive particle and genitive DP complement. It (in a FG) expresses or conveys the meaning of possessiveness, something like of in English. There are two types of ħaqq in Yemeni Arabic: one not exhibiting agreement with the head N, and another exhibiting it. -

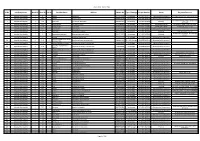

Sl No Localbody Name Ward No Door No Sub No Resident Name Address Mobile No Type of Damage Unique Number Status Rejection Remarks

Flood 2019 - Vythiri Taluk Sl No Localbody Name Ward No Door No Sub No Resident Name Address Mobile No Type of Damage Unique Number Status Rejection Remarks 1 Kalpetta Municipality 1 0 kamala neduelam 8157916492 No damage 31219021600235 Approved(Disbursement) RATION CARD DETAILS NOT AVAILABLE 2 Kalpetta Municipality 1 135 sabitha strange nivas 8086336019 No damage 31219021600240 Disbursed to Government 3 Kalpetta Municipality 1 138 manjusha sukrutham nedunilam 7902821756 No damage 31219021600076 Pending THE ADHAR CARD UPDATED ANOTHER ACCOUNT 4 Kalpetta Municipality 1 144 devi krishnan kottachira colony 9526684873 No damage 31219021600129 Verified(LRC Office) NO BRANCH NAME AND IFSC CODE 5 Kalpetta Municipality 1 149 janakiyamma kozhatatta 9495478641 >75% Damage 31219021600080 Verified(LRC Office) PASSBOOK IS NO CLEAR 6 Kalpetta Municipality 1 151 anandavalli kozhathatta 9656336368 No damage 31219021600061 Disbursed to Government 7 Kalpetta Municipality 1 16 chandran nedunilam st colony 9747347814 No damage 31219021600190 Withheld PASSBOOK NOT CLEAR 8 Kalpetta Municipality 1 16 3 sangeetha pradeepan rajasree gives nedunelam 9656256950 No damage 31219021600090 Withheld No damage type details and damage photos 9 Kalpetta Municipality 1 161 shylaja sasneham nedunilam 9349625411 No damage 31219021600074 Disbursed to Government Manjusha padikkandi house 10 Kalpetta Municipality 1 172 3 maniyancode padikkandi house maniyancode 9656467963 16 - 29% Damage 31219021600072 Disbursed to Government 11 Kalpetta Municipality 1 175 vinod madakkunnu colony -

Ethnographic Series, Sidhi, Part IV-B, No-1, Vol-V

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUMEV, PART IV-B, No.1 ETHNOGRAPHIC SERIES GUJARAT Preliminary R. M. V ANKANI, investigation Tabulation Officer, and draft: Office of the CensuS Superintendent, Gujarat. SID I Supplementary V. A. DHAGIA, A NEGROID L IBE investigation: Tabulation Officer, Office of the Census Superintendent, OF GU ARAT Gujarat. M. L. SAH, Jr. Investigator, Office of the Registrar General, India. Fieta guidance, N. G. NAG, supervision and Research Officer, revised draft: Office of the Registrar General, India. Editors: R. K. TRIVEDI, Su perintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat. B. K. Roy BURMAN, Officer on Special Duty, (Handicrafts and Social Studies), Office of the Registrar General, India. K. F. PATEL, R. K. TRIVEDI Deputy Superintendent of Census Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat. Operations, Gujarat N. G. NAG, Research Officer, Office' of the Registrar General, India. CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-Gujarat is being published in the following parts: '" I-A(i) General Report '" I-A(ii)a " '" I-A(ii)b " '" I-A(iii) General Report-Economic Trends and Projections :« I-B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey :I' I-C Subsidiary Tables '" II-A General Population Tables '" II-B(I) General Economic Tables (Tables B-1 to B-IV-C) '" II-B(2) General Economic Tables (Tables B-V to B-IX) '" II-C Cultural and Migration Tables :t< III Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) "'IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments :t<IV-B Housing and Establishment -

Path(S) of Remembrance: Memory, Pilgrimage, and Transmission in a Transatlantic Sufi Community”

“Path(s) of Remembrance: Memory, Pilgrimage, and Transmission in a Transatlantic Sufi Community” By Jaison Carter A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mariane Ferme, Chair Professor Charles Hirschkind Professor Stefania Pandolfo Professor Ula Y. Taylor Spring 2018 Abstract “Path(s) of Remembrance: Memory, Pilgrimage, and Transmission in a Transatlantic Sufi Community” by Jaison Carter Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Mariane Ferme, Chair The Mustafawiyya Tariqa is a regional spiritual network that exists for the purpose of assisting Muslim practitioners in heightening their level of devotion and knowledges through Sufism. Though it was founded in 1966 in Senegal, it has since expanded to other locations in West and North Africa, Europe, and North America. In 1994, protegé of the Tariqa’s founder and its most charismatic figure, Shaykh Arona Rashid Faye al-Faqir, relocated from West Africa to the United States to found a satellite community in Moncks Corner, South Carolina. This location, named Masjidul Muhajjirun wal Ansar, serves as a refuge for traveling learners and place of worship in which a community of mostly African-descended Muslims engage in a tradition of remembrance through which techniques of spiritual care and healing are activated. This dissertation analyzes the physical and spiritual trajectories of African-descended Muslims through an ethnographic study of their healing practices, migrations, and exchanges in South Carolina and in Senegal. By attending to manner in which the Mustafawiyya engage in various kinds of embodied religious devotions, forms of indebtedness, and networks within which diasporic solidarities emerge, this project explores the dispensations and transmissions of knowledge to Sufi practitioners across the Atlantic that play a part in shared notions of Black Muslimness. -

Cognate Words in Mehri and Hadhrami Arabic

Cognate Words in Mehri and Hadhrami Arabic Hassan Obeid Alfadly* Khaled Awadh Bin Mukhashin** Received: 18/3/2019 Accepted: 2/5/2019 Abstract The lexicon is one important source of information to establish genealogical relations between languages. This paper is an attempt to describe the lexical similarities between Mehri and Hadhrami Arabic and to show the extent of relatedness between them, a very little explored and described topic. The researchers are native speakers of Hadhrami Arabic and they paid many field visits to the area where Mehri is spoken. They used the Swadesh list to elicit their data from more than 20 Mehri informants and from Johnston's (1987) dictionary "The Mehri Lexicon and English- Mehri Word-list". The researchers employed lexicostatistical techniques to analyse their data and they found out that Mehri and Hadhrmi Arabic have so many cognate words. This finding confirms Watson (2011) claims that Arabic may not have replaced all the ancient languages in the South-Western Arabian Peninsula and that dialects of Arabic in this area including Hadhrami Arabic are tinged, to a greater or lesser degree, with substrate features of the Pre- Islamic Ancient and Modern South Arabian languages. Introduction: three branches including Central Semitic, Historically speaking, the Semitic language Ethiopian and Modern south Arabian languages family from which both of Arabic and Mehri (henceforth MSAL). Though Arabic and Mehri descend belong to a larger family of languages belong to the West Semitic, Arabic descends called Afro-Asiatic or Hamito-Semitic that from the Central Semitic and Mehri from includes Semitic, Egyptian, Cushitic, Omotic, (MSAL) which consists of two branches; the Berber and Chadic (Rubin, 2010). -

Dictionary of Martyrs: India's Freedom Struggle

DICTIONARY OF MARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala ii Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 DICTIONARY OF MARTYRSMARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala General Editor Arvind P. Jamkhedkar Chairman, ICHR Executive Editor Rajaneesh Kumar Shukla Member Secretary, ICHR Research Consultant Amit Kumar Gupta Research and Editorial Team Ashfaque Ali Md. Naushad Ali Md. Shakeeb Athar Muhammad Niyas A. Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF IDNIA AND INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH iv Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH First Edition 2018 Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE Government of India and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH 35, Ferozeshah Road, New Delhi - 110 001 © ICHR & Ministry of Culture, GoI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 978-81-938176-1-2 Printed in India by MANAK PUBLICATIONS PVT. LTD B-7, Saraswati Complex, Subhash Chowk, Laxmi Nagar, New Delhi 110092 INDIA Phone: 22453894, 22042529 [email protected] State Co-ordinators and their Researchers Andhra Pradesh & Telangana Karnataka (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) V. Ramakrishna B. Surendra Rao S.K. Aruni Research Assistants Research Assistants V. Ramakrishna Reddy A.B. Vaggar I. Sudarshan Rao Ravindranath B.Venkataiah Tamil Nadu Kerala (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) N.