Like a Bomb Going Off

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES Composers

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers A-G KHAIRULLO ABDULAYEV (b. 1930, TAJIKISTAN) Born in Kulyab, Tajikistan. He studied composition at the Moscow Conservatory under Anatol Alexandrov. He has composed orchestral, choral, vocal and instrumental works. Sinfonietta in E minor (1964) Veronica Dudarova/Moscow State Symphony Orchestra ( + Poem to Lenin and Khamdamov: Day on a Collective Farm) MELODIYA S10-16331-2 (LP) (1981) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where he studied under Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. His other Symphonies are Nos. 1 (1962), 3 in B flat minor (1967) and 4 (1969). Symphony No. 2 in E minor (1964) Valentin Katayev/Byelorussian State Symphony Orchestra ( + Vagner: Suite for Symphony Orchestra) MELODIYA D 024909-10 (LP) (1969) VASIF ADIGEZALOV (1935-2006, AZERBAIJAN) Born in Baku, Azerbaijan. He studied under Kara Karayev at the Azerbaijan Conservatory and then joined the staff of that school. His compositional catalgue covers the entire range of genres from opera to film music and works for folk instruments. Among his orchestral works are 4 Symphonies of which the unrecorded ones are Nos. 1 (1958) and 4 "Segah" (1998). Symphony No. 2 (1968) Boris Khaikin/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1968) ( + Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 3, Poem Exaltation for 2 Pianos and Orchestra, Africa Amidst MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Symphonies A-G Struggles, Garabagh Shikastasi Oratorio and Land of Fire Oratorio) AZERBAIJAN INTERNATIONAL (3 CDs) (2007) Symphony No. -

2.Documentals, Pel.Lícules, Concerts, Ballet, Teatre

2.DOCUMENTALS, PEL.LÍCULES, CONCERTS, BALLET, TEATRE..... L’aparició del format DVD ha empès a que molts teatres, televisions, productores, etc hagin decidit reeeditar programes que havien contribuït a popularitzar i divulgar diferents aspectes culturals. També permet elaborar documents que en altres formats son prohibitius, per això avui en dia, hi ha molt a on triar. En aquest arxiu trobareu: -- Documentals a) dedicats a Wagner o la seva obra b) dedicats a altres músics, obres, cantants, directors, ... -- Grabacions de concerts i recitals a) D’ obres wagnerianes b) D’ altres obres i compositors -- Pel.lícules que ens acosten al món de la música -- Ballet clàssic -- Teatre clàssic Associació Wagneriana. Apartat postal 1159 Barcelona Http://www. associaciowagneriana.com. [email protected] DOCUMENTALS A) DEDICATS A WAGNER O LA SEVA OBRA 1. “The Golden Ring” DVD: DECCA Film de la BBC que mostre com es va grabar en disc La Tetralogia en 1965, dirigida per Georg Solti. El DVD es centre en la grabació del Götterdämmerung. Molt recomenable 2. Sing Faster. The Stagehands’Ring Cycle. DVD: Docurama Filmat per John Else presenta com es va preparar el montatge de la Tetralogia a San Francisco. Interesant ja que mostra la feina que cal realitzar en diferents àmbits per organitzar un Anell, però malhauradament la producció escenogrficament és bastant dolenta. 3. “Parsifal” DVD: Kultur. Del director Tony Palmer, el que va firmar la biografia deplorable del compositor Wagner, aquest documental ens apropa i allunya del Parsifal de Wagner. Ens apropa en les explicacions de Domingo i ens allunya amb les bestieses de Gutman. Prescindible. B) DEDICATS A ALTRES MÚSICS, OBRES, CANTANTS, DIRECTORS, .. -

Downloading Case in U.S

daijesti 109 The Digest debiuti papuna SariqaZe 105 The Debut Papuna Sharikadze saqarTvelos saavtoro uflebaTa asociacia reformirebis procesi grZeldeba 96 Georgian Copyright Association The Reform Process Continues stumari daviT asaTiani - „Microsoft saqarTvelos“ generaluri direqtori 90 The Guest David Asatiani – The General Director of the “Microsoft Georgia” qarTvelebi ucxoeTSi manana menabde 85 Georgians Abroad Manana Menabde precedentebi 82 Precedents problematika daviT sayvareliZe, rezo kiknaZe, vaxo babunaSvili, anton balanCivaZe 56 Problems David Sakvarelidze, Rezo Kiknadze, Vakho Babunashvili, Anton Balanchivadz subieqturi sivrce nika rurua, aka morCilaZe, irina demetraZe 26 The Subjective Space Nika Rurua, Aka Morchiladze, Irina Demetradze portreti vaxtang Wabukiani 20 The Portrait Vakhtang Chabukiani mTavari Tema interviu CISAC-is evropul sakiTxTa direqtor - mitko CatalbaSevTan 14 The Main Topic Interview with CISAC European Affairs Director, Mitko Chatalbashev Semecneba saavtoro uflebebi teqnologiebisa da ekonomikis ganviTarebis kvaldakval 6 Overview Copyrights in Tact with Development of Technologies and Economy gamomcemeli: saqarTvelos saavtoro uflebaTa asociacia/Publisher: Georgian Copyright Association (GCA) saqarTvelo, 0171 Tbilisi, kostavas q. 63 / 63 Kostava str. 0171 Tbilisi, Georgia tel.:/Tel: +995 32 2 7887 www.gca.ge [email protected] aRmasrulebeli menejeri: giorgi salayaia/Executive Manager: Giorgi Salakaia nomerze muSaobdnen: Tamar kemularia, irina demetraZe, xaTuna gogiSvili/The edition was prepared by: Tamar Kemularia, -

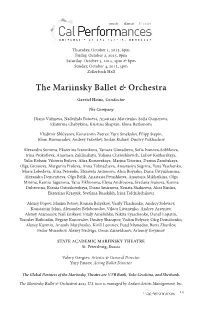

The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra

Thursday, October 1, 2015, 8pm Friday, October 2, 2015, 8pm Saturday, October 3, 2015, 2pm & 8pm Sunday, October 4, 2015, 3pm Zellerbach Hall The Mariinsky Ballet & Orchestra Gavriel Heine, Conductor The Company Diana Vishneva, Nadezhda Batoeva, Anastasia Matvienko, Sofia Gumerova, Ekaterina Chebykina, Kristina Shapran, Elena Bazhenova Vladimir Shklyarov, Konstantin Zverev, Yury Smekalov, Filipp Stepin, Islom Baimuradov, Andrey Yakovlev, Soslan Kulaev, Dmitry Pukhachov Alexandra Somova, Ekaterina Ivannikova, Tamara Gimadieva, Sofia Ivanova-Soblikova, Irina Prokofieva, Anastasia Zaklinskaya, Yuliana Chereshkevich, Lubov Kozharskaya, Yulia Kobzar, Viktoria Brileva, Alisa Krasovskaya, Marina Teterina, Darina Zarubskaya, Olga Gromova, Margarita Frolova, Anna Tolmacheva, Anastasiya Sogrina, Yana Yaschenko, Maria Lebedeva, Alisa Petrenko, Elizaveta Antonova, Alisa Boyarko, Daria Ustyuzhanina, Alexandra Dementieva, Olga Belik, Anastasia Petushkova, Anastasia Mikheikina, Olga Minina, Ksenia Tagunova, Yana Tikhonova, Elena Androsova, Svetlana Ivanova, Ksenia Dubrovina, Ksenia Ostreikovskaya, Diana Smirnova, Renata Shakirova, Alisa Rusina, Ekaterina Krasyuk, Svetlana Russkikh, Irina Tolchilschikova Alexey Popov, Maxim Petrov, Roman Belyakov, Vasily Tkachenko, Andrey Soloviev, Konstantin Ivkin, Alexander Beloborodov, Viktor Litvinenko, Andrey Arseniev, Alexey Atamanov, Nail Enikeev, Vitaly Amelishko, Nikita Lyaschenko, Daniil Lopatin, Yaroslav Baibordin, Evgeny Konovalov, Dmitry Sharapov, Vadim Belyaev, Oleg Demchenko, Alexey Kuzmin, Anatoly Marchenko, -

Georgian Country and Culture Guide

Georgian Country and Culture Guide მშვიდობის კორპუსი საქართველოში Peace Corps Georgia 2017 Forward What you have in your hands right now is the collaborate effort of numerous Peace Corps Volunteers and staff, who researched, wrote and edited the entire book. The process began in the fall of 2011, when the Language and Cross-Culture component of Peace Corps Georgia launched a Georgian Country and Culture Guide project and PCVs from different regions volunteered to do research and gather information on their specific areas. After the initial information was gathered, the arduous process of merging the researched information began. Extensive editing followed and this is the end result. The book is accompanied by a CD with Georgian music and dance audio and video files. We hope that this book is both informative and useful for you during your service. Sincerely, The Culture Book Team Initial Researchers/Writers Culture Sara Bushman (Director Programming and Training, PC Staff, 2010-11) History Jack Brands (G11), Samantha Oliver (G10) Adjara Jen Geerlings (G10), Emily New (G10) Guria Michelle Anderl (G11), Goodloe Harman (G11), Conor Hartnett (G11), Kaitlin Schaefer (G10) Imereti Caitlin Lowery (G11) Kakheti Jack Brands (G11), Jana Price (G11), Danielle Roe (G10) Kvemo Kartli Anastasia Skoybedo (G11), Chase Johnson (G11) Samstkhe-Javakheti Sam Harris (G10) Tbilisi Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Workplace Culture Kimberly Tramel (G11), Shannon Knudsen (G11), Tami Timmer (G11), Connie Ross (G11) Compilers/Final Editors Jack Brands (G11) Caitlin Lowery (G11) Conor Hartnett (G11) Emily New (G10) Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Compilers of Audio and Video Files Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Irakli Elizbarashvili (IT Specialist, PC Staff) Revised and updated by Tea Sakvarelidze (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator) and Kakha Gordadze (Training Manager). -

El Ballet De Geòrgia Presenta «Fuenteovejuna», «Chopiniana» I

Cultura i mitjans | | Actualitzat el 17/12/2019 a les 13:30 El Ballet de Geòrgia presenta «Fuenteovejuna», «Chopiniana» i «L'Ocell de foc» a Terrassa La companyia de dansa oferirà una doble programació per aquest cap de setmana al Centre Cultural Terrassa L'Ocell de Foc del Ballet de Geòrgia. | Cedida L'escenari del Centre Cultural Terrassa (http://www.fundacioct.cat/) acull, aquest cap de setmana de desembre, una doble programació del Ballet de Geòrgia. El dissbte 21 de desembre a les 20 h la companyia presenta el clàssic de Lope de Vega, Fuenteovejuna i el dilluns 23 de desembre a les 20.30 h homenatja a Fokin amb Chopiniana i L'Ocell de foc. Fuenteovejuna (escrita en 1613) és una de les obres més conegudes de Lope de Vega i una de les més representades de tots els temps. La història està basada en un fet real que va succeir al segle XV a un pobe andalús. Davant els abusos del comendador Fernán Gómez, tot el poble es va alçar contra ell i el va matar atroçment. El ballet, anomenat també Laurencia, es va estrenar el 1939 a l'Òpera de Kirov i el Ballet Theatre i va tenir un gran èxit a tota l'antiga URSS, en un moment en què a la Unió Soviètica es considerava el coreodrama l'única forma acceptable de ballet contemporani. Al mateix temps, la història d'una revolució camperola era òbviament el tema ideal per a un ballet soviètic. La coreografia va a càrrec de Nina Ananiashvili, sobre l'original de Vakhtang Chabukiani i música d'Alexander Krein. -

Giselle Saison 2015-2016

Giselle Saison 2015-2016 Abonnez-vous ! sur www.theatreducapitole.fr Opéras Le Château de Barbe-Bleue Bartók (octobre) Le Prisonnier Dallapiccola (octobre) Rigoletto Verdi (novembre) Les Caprices de Marianne Sauguet (janvier) Les Fêtes vénitiennes Campra (février) Les Noces de Figaro Mozart (avril) L’Italienne à Alger Rossini (mai) Faust Gounod (juin) Ballets Giselle Belarbi (décembre) Coppélia Jude (mars) Paradis perdus Belarbi, Rodriguez (avril) Paquita Grand Pas – L’Oiseau de feu Vinogradov, Béjart (juin) RCS TOULOUSE B 387 987 811 - © Alexander Gouliaev - © B 387 987 811 TOULOUSE RCS Giselle Midis du Capitole, Chœur du Capitole, Cycle Présences vocales www.fnac.com Sur l’application mobile La Billetterie, et dans votre magasin Fnac et ses enseignes associées www.theatreducapitole.fr saison 2015/16 du capitole théâtre 05 61 63 13 13 Licences d’entrepreneur de spectacles 1-1052910, 2-1052938, 3-1052939 THÉÂTRE DU CAPITOLE Frédéric Chambert Directeur artistique Janine Macca Administratrice générale Kader Belarbi Directeur de la danse Julie Charlet (Giselle) et Davit Galstyan (Albrecht) en répétition dans Giselle, Ballet du Capitole, novembre 2015, photo David Herrero© Giselle Ballet en deux actes créé le 28 juin 1841 À l’Académie royale de Musique de Paris (Salle Le Peletier) Sur un livret de Théophile Gautier et de Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges D’après Heinrich Heine Nouvelle version d’après Jules Perrot et Jean Coralli (1841) Adolphe Adam musique Kader Belarbi chorégraphie et mise en scène Laure Muret assistante-chorégraphe Thierry Bosquet décors Olivier Bériot costumes Marc Deloche architecte-bijoutier Sylvain Chevallot lumières Monique Loudières, Étoile du Ballet de l’Opéra National de Paris maître de ballet invité Emmanuelle Broncin et Minh Pham maîtres de ballet Nouvelle production Ballet du Capitole Kader Belarbi direction Orchestre national du Capitole Philippe Béran direction Durée du spectacle : 2h25 Acte I : 60 min. -

St. Petersburg Is Recognized As One of the Most Beautiful Cities in the World. This City of a Unique Fate Attracts Lots of Touri

I love you, Peter’s great creation, St. Petersburg is recognized as one of the most I love your view of stern and grace, beautiful cities in the world. This city of a unique fate The Neva wave’s regal procession, The grayish granite – her bank’s dress, attracts lots of tourists every year. Founded in 1703 The airy iron-casting fences, by Peter the Great, St. Petersburg is today the cultural The gentle transparent twilight, capital of Russia and the second largest metropolis The moonless gleam of your of Russia. The architectural look of the city was nights restless, When I so easy read and write created while Petersburg was the capital of the Without a lamp in my room lone, Russian Empire. The greatest architects of their time And seen is each huge buildings’ stone worked at creating palaces and parks, cathedrals and Of the left streets, and is so bright The Admiralty spire’s flight… squares: Domenico Trezzini, Jean-Baptiste Le Blond, Georg Mattarnovi among many others. A. S. Pushkin, First named Saint Petersburg in honor of the a fragment from the poem Apostle Peter, the city on the Neva changed its name “The Bronze Horseman” three times in the XX century. During World War I, the city was renamed Petrograd, and after the death of the leader of the world revolution in 1924, Petrograd became Leningrad. The first mayor, Anatoly Sobchak, returned the city its historical name in 1991. It has been said that it is impossible to get acquainted with all the beauties of St. -

Image to PDF Conversion Tools

Complete Radio Programs By The Hour, A Page To A Day 4 HF Long R'as'e ,Nq G 5 Short Wav'e - Cents News Spots °RADIO <t`i,S the Copy & Pic turcs R PPQ SI.5O Year Volume HI, N. 24 WEEK ENDING JUNE. 22, 1934 * Published \X'eck y This and That Senate Inquiry Into Fitness of U. S. ByMorris Hastings AT LONG LAST FRANK Radio Commissioners Is demanded BLACK has given the much publicized premiere of GLIERE'S "The Red Poppy," music for a ballet that is now all the rage in Dickinson Soviet Russia. 180, 000, 000 Sets in World Use Those who did not expect too much of the Marriages (.an Be Happy Of Iowa Is 1 music probably were not dis- U. S. Leading a p pointed. In Brig/:t World of Radio Accusing Those who had All Countries hoped f o r By The MICROPHONE'S 11"ashingtollt s o mething A Few of the Stars Special Correspondent original a n d In Tabulation arresting were Display Famed Charges in the United States Senate by Senator L. J. DicKIN- let down. A report made by the Interna- ISON (R) of Iowa, that the Fed. It isn't had tionale de Radiodiffusion of Emotion music not at eral Radio Commission is influ- - Geneva estimates that 20,000,000 enced decisions all bad. It By JOHN McART in its by politics radio sets were sold throughout ,..one as a bombshell. simply i s n ' t the world during the year 1933, Come, come, my good director, The Iowan has introduced a good enough. -

The Bolshoi Meets Bolshevism: Moving Bodies and Body Politics, 1917-1934

THE BOLSHOI MEETS BOLSHEVISM: MOVING BODIES AND BODY POLITICS, 1917-1934 By Douglas M. Priest A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History – Doctor of Philosophy 2016 ABSTRACT THE BOLSHOI MEETS BOLSHEVISM: MOVING BODIES AND BODY POLITICS, 1917- 1934 By Douglas M. Priest Following the Russian Revolution in 1917, the historically aristocratic Bolshoi Ballet came face to face with Bolshevik politics for the first time. Examining the collision of this institution and its art with socialist politics through the analysis of archival documents, published material, and ballets themselves, this dissertation explains ballet’s persisting allure and cultural power in the early Soviet Union. The resulting negotiation of aesthetic and political values that played out in a discourse of and about bodies on the Bolshoi Theater’s stage and inside the studios of the Bolshoi’s Ballet School reveals Bolshevik uncertainty about the role of high culture in their new society and helped to define the contentious relationship between old and new in the 1920s. Furthermore, the most hostile attack on ballet coming from socialists, anti- formalism, paradoxically provided a rhetorical shield for classical ballet by silencing formalist critiques. Thus, the collision resulted not in one side “winning,” but rather in a contested environment in which dancers embodied both tradition and revolution. Finally, the persistence of classical ballet in the 1920s, particularly at the Ballet School, allowed for the Bolshoi Ballet’s eventual ascendancy to world-renowned ballet company following the second World War. This work illuminates the Bolshoi Ballet’s artistic work from 1917 to 1934, its place and importance in the context of early Soviet culture, and the art form’s cultural power in the Soviet Union. -

World War I Biographies WWIBIO 9/26/03 12:35 PM Page 3

WWIBIO 9/26/03 12:35 PM Page 1 World War I Biographies WWIBIO 9/26/03 12:35 PM Page 3 World War I Biographies Tom Pendergast and Sara Pendergast Christine Slovey, Editor WWIbioFM 7/28/03 8:53 PM Page iv Tom Pendergast and Sara Pendergast Staff Christine Slovey, U•X•L Senior Editor Julie L. Carnagie, U•X•L Contributing Editor Carol DeKane Nagel, U•X•L Managing Editor Tom Romig, U•X•L Publisher Pamela A.E. Galbreath, Senior Art Director (Page design) Jennifer Wahi, Art Director (Cover design) Shalice Shah-Caldwell, Permissions Associate (Images) Robyn Young, Imaging and Multimedia Content Editor Pamela A. Reed, Imaging Coordinator Robert Duncan, Imaging Specialist Rita Wimberly, Senior Buyer Evi Seoud, Assistant Manager, Composition Purchasing and Electronic Prepress Linda Mahoney, LM Design, Typesetting Cover Photos: Woodrow Wilson and Manfred von Richthofen reproduced by permission of AP/Wide World Photos, Inc. orld War I: Biographies orld War Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data W Pendergast, Tom. World War I biographies / Tom Pendergast, Sara Pendergast p.cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: A collection of thirty biographies of world figures who played important roles in World War I, including Mata Hari, T.E. Lawrence, and Alvin C. York. ISBN 0-7876-5477-9 1. World War, 1914-1918—Biography—Dictionaries—-Juvenile literature. [1. World War, 1914-1918—Biography. 2. Soldiers.] I. Title: World War One biogra- phies. II. Title: World War 1 biographies. III. Pendergast, Sara. IV. Title. D522.7 .P37 2001 940.3'092'2--dc21 2001053162 This publication is a creative work copyrighted by U•X•L and fully protected by all applicable copyright laws, as well as by misappropriation, trade secret, unfair competition, and other applicable laws. -

2017 - 2018 SEASON World Ballet Stars • Giselle • the Nutcracker • Peter Pan Lightwire Theater: a Very Electric Christmas

2017 - 2018 SEASON World Ballet Stars • Giselle • The Nutcracker • Peter Pan Lightwire Theater: A Very Electric Christmas 2017-2018 SEASON PASSION. DISCIPLINE. GRACE. Attributes that both ballet dancers and our expert group of medical professionals possess. At Fort Walton Beach Medical Center, each member of our team plays an important part in serving our patients with the highest quality care. We are proud to support the ballet in its mission to share the beauty and artistry of dance with our community. Exceptional People. Exceptional Care. 23666 Ballet 5.5 x 8.5.indd 1 8/26/2016 3:47:56 PM MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR Dear Friends: Welcome to the 48th season of the Northwest Florida Ballet! With the return of the Northwest Florida Ballet Symphony Orchestra and FIVE productions at venues all along the Emerald Coast, we have proven our commitment to elevating the performing arts in the communities we serve. As friends of NFB and valued patrons of the arts, we have listened to your feedback and identified new performance locations and expanded use of others to continue bringing you the world-class productions our organization is known for. Todd Eric Allen, NFB Artistic Director & CEO The season begins with World Ballet Stars, a main stage production at the Mattie Kelly Arts Center in September. Through our expanded partnership with Grand Boulevard, we will present Giselle to the community as a free outdoor performance in Grand Park in October. We return to the Mattie Kelly Arts Center in November for our 38th annual production of The Nutcracker. In December we bring back the electrifying Lightwire Theater with A Very Electric Christmas for two performances at the Destin United Methodist Church Life Center.