Raf Airfield Defense

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wisconsin Veterans Museum Research Center Transcript of An

Wisconsin Veterans Museum Research Center Transcript of an Oral History Interview with WARREN H. WEBSTER Pilot, Royal Canadian Air Force and U.S. Air Force, World War II 2000 OH 357 1 OH 357 Webster, Warren H., (1915- ). Oral History Interview, 2000. User Copy: 1 sound cassette (ca. 44 min.); analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Master Copy: 1 sound cassette (ca. 44 min.); analog, 1 7/8 ips, mono. Video Recording: 1 videorecording (ca. 44 min.); ½ inch, color. Transcript: 0.1 linear ft. (1 folder). Military Papers: 0.1 linear ft. (1 folder). Abstract: Warren Webster, a Madison, Wisconsin native, discusses his World War II service with the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and later the U.S. Air Force flying close air support. Webster talks about being turned down by the Air Corps because he did not have two years of college, enlisting in the Canadian Air Force, and basic training at Toronto. He estimates that twenty percent of those in flying school were Americans. Webster comments on getting previous flight training as a civilian, flight training in Tiger Moth and Avro Anson planes, flight instructor school in Trenton (Ontario), and serving as an assistant flight instructor. Webster mentions having difficulty getting promoted. He discusses duty as a check pilot and transfer in 1944 to the American Air Force. Sent to France with the 514th Squadron of the 406th Air Group, he touches upon flying support and fighter escort during the Battle of the Bulge. He speaks of different types of bombs he carried, mentions he once missed some tanks and hit a hospital by mistake, and describes the effectiveness of dive bombing tactics using machine guns. -

Premises, Sites Etc Within 30 Miles of Harrington Museum Used for Military Purposes in the 20Th Century

Premises, Sites etc within 30 miles of Harrington Museum used for Military Purposes in the 20th Century The following listing attempts to identify those premises and sites that were used for military purposes during the 20th Century. The listing is very much a works in progress document so if you are aware of any other sites or premises within 30 miles of Harrington, Northamptonshire, then we would very much appreciate receiving details of them. Similarly if you spot any errors, or have further information on those premises/sites that are listed then we would be pleased to hear from you. Please use the reporting sheets at the end of this document and send or email to the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum, Sunnyvale Farm, Harrington, Northampton, NN6 9PF, [email protected] We hope that you find this document of interest. Village/ Town Name of Location / Address Distance to Period used Use Premises Museum Abthorpe SP 646 464 34.8 km World War 2 ANTI AIRCRAFT SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY Northamptonshire The site of a World War II searchlight battery. The site is known to have had a generator and Nissen huts. It was probably constructed between 1939 and 1945 but the site had been destroyed by the time of the Defence of Britain survey. Ailsworth Manor House Cambridgeshire World War 2 HOME GUARD STORE A Company of the 2nd (Peterborough) Battalion Northamptonshire Home Guard used two rooms and a cellar for a company store at the Manor House at Ailsworth Alconbury RAF Alconbury TL 211 767 44.3 km 1938 - 1995 AIRFIELD Huntingdonshire It was previously named 'RAF Abbots Ripton' from 1938 to 9 September 1942 while under RAF Bomber Command control. -

B&W Real.Xlsx

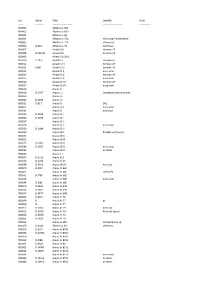

NO REGN TYPE OWNER YEAR ‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ X00001 Albatros L‐68C X00002 Albatros L‐68D X00003 Albatros L‐69 X00004 Albatros L‐72C Hamburg Fremdenblatt X00005 Albatros L‐72C striped c/s X00006 D‐961 Albatros L‐73 Lufthansa X00007 Aviatik B.II German AF X00008 B.558/15 Aviatik B.II German AF X00009 Aviatik PG.20/2 X00010 C.1952 Aviatik C.I German AF X00011 Aviatik C.III German AF X00012 6306 Aviatik C.IX German AF X00013 Aviatik D.II nose view X00014 Aviatik D.III German AF X00015 Aviatik D.III nose view X00016 Aviatik D.VII German AF X00017 Aviatik D.VII nose view X00018 Arado J.1 X00019 D‐1707 Arado L.1 Ostseebad Warnemunde X00020 Arado L.II X00021 D‐1874 Arado L.II X00022 D‐817 Arado S.I DVL X00023 Arado S.IA nose view X00024 Arado S.I modified X00025 D‐1204 Arado SC.I X00026 D‐1192 Arado SC.I X00027 Arado SC.Ii X00028 Arado SC.II nose view X00029 D‐1984 Arado SC.II X00030 Arado SD.1 floatplane @ (poor) X00031 Arado SD.II X00032 Arado SD.III X00033 D‐1905 Arado SSD.I X00034 D‐1905 Arado SSD.I nose view X00035 Arado SSD.I on floats X00036 Arado V.I X00037 D‐1412 Arado W.2 X00038 D‐2994 Arado Ar.66 X00039 D‐IGAX Arado AR.66 Air to Air X00040 D‐IZOF Arado Ar.66C X00041 Arado Ar.68E Luftwaffe X00042 D‐ITEP Arado Ar.68E X00043 Arado Ar.68E nose view X00044 D‐IKIN Arado Ar.68F X00045 D‐2822 Arado Ar.69A X00046 D‐2827 Arado Ar.69B X00047 D‐EPYT Arado Ar.69B X00048 D‐IRAS Arado Ar.76 X00049 D‐ Arado Ar.77 @ X00050 D‐ Arado Ar.77 X00051 D‐EDCG Arado Ar.79 Air to Air X00052 D‐EHCR -

RAF Variant Rules #1.45 Mar 2014

RAF Variant Rules #1.45 Mar 2014 By Simon D Blackwell Introduction These rules are the final updated and expanded version of my earlier submissions #1.0-#1.4. They now incorporate the Miles Master M.24 Emergency fighter, as well as a tweak to the stats of the Fw.200. Also included are all the previous new aircraft types and the hypothetical ones of which all either were or could have been seen over the skies of Sussex, Kent and the Thames estuary in 1940. I was prompted to write these rules after playing the original game a few times and dimly remembering a turret armed British fighter that had no forward firing machine guns. The fighter in question was the Boulton Paul Defiant of which 2 Sqns served in the Battle of Britain. Left out of the game I suspect owing to its combat record which can only be described as disastrous I decided for historical accuracy more than attempting to change the balance of the game to introduce these much maligned aircraft to the game. After a few plays my appetite was whetted sufficiently to research introducing other aircraft not featured in the original game. As the reader will note from the sheer number of new aircraft types listed below, this became a much larger project than originally envisaged but proved far more interesting and enjoyable. I also decided to keep from the original variant rules just 1 elite RAF Sqn as there is an alternative unit to choose from that has the same stats as the withdrawn unit (263 Sqn Whirlwind). -

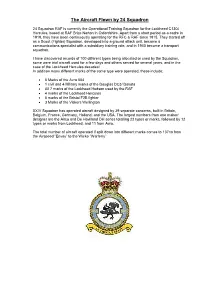

The Aircraft Flown by 24 Squadron

The Aircraft Flown by 24 Squadron 24 Squadron RAF is currently the Operational Training Squadron for the Lockheed C130J Hercules, based at RAF Brize Norton in Oxfordshire. Apart from a short period as a cadre in 1919, they have been continuously operating for the RFC & RAF since 1915. They started off as a Scout (Fighter) Squadron, developed into a ground attack unit, became a communications specialist with a subsidiary training role, and in 1940 became a transport squadron. I have discovered records of 100 different types being allocated or used by the Squadron, some were trial aircraft used for a few days and others served for several years, and in the case of the Lockheed Hercules decades! In addition many different marks of the same type were operated, these include; 5 Marks of the Avro 504 1 civil and 4 Military marks of the Douglas DC3/ Dakota All 7 marks of the Lockheed Hudson used by the RAF 4 marks of the Lockheed Hercules 5 marks of the Bristol F2B fighter 3 Marks of the Vickers Wellington XXIV Squadron has operated aircraft designed by 39 separate concerns, built in Britain, Belgium, France, Germany, Holland, and the USA. The largest numbers from one maker/ designer are the Airco and De Havilland DH series totalling 22 types or marks, followed by 12 types or marks from Lockheed, and 11 from Avro. The total number of aircraft operated if split down into different marks comes to 137no from the Airspeed “Envoy” to the Wicko “Warferry” Earliest Days 24 Squadron was formed at Hounslow as an offshoot of 17 Squadron on the 1st September 1915 initially under the command of Capt A G Moore. -

Aircraft Crash Sites at Sea: a Scoping Study

Wessex Archaeology Aircraft Crash Sites at Sea A Scoping Study Archaeological Desk-based Assessment Ref: 66641.02 February 2008 AIRCRAFT CRASH SITES AT SEA: A SCOPING STUDY ARCHAEOLOGICAL DESK-BASED ASSESSMENT:FINAL REPORT Prepared by: Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park Salisbury WILTSHIRE SP4 6EB Prepared for: English Heritage February 2008 Ref: 66641.02 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2008 Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No.28778 Aircraft Crash Sites at Sea: A Scoping Study Wessex Archaeology 66641.02 AIRCRAFT CRASH SITES AT SEA: A SCOPING STUDY ARCHAEOLOGICAL DESK-BASED ASSESSMENT:FINAL REPORT Ref: 66641.02 Summary Wessex Archaeology have been funded by English Heritage through the Aggregates Levy Sustainability Fund to undertake a scoping study to identify current gaps in data and understanding relating to aircraft crash sites at sea. The study arises partly out of the discovery of aircraft parts and associated human remains as a result of marine aggregate dredging. The objectives of the Scoping Study are as follows: x to review existing literature relating to the archaeology of aircraft crash sites at sea, existing guidance, and the legislative context; x to clarify the range and archaeological potential of aircraft crash sites, by presenting examples of aircraft crash sites, which will include a range of site conditions and mechanisms affecting site survival, their management and investigation; x to establish the relationship, in terms of numbers and composition, between the National Monuments Record -

MAIDENHEAD HERITAGE CENTRE Transcript

MAIDENHEAD HERITAGE CENTRE Transcript of the Diaries of Capt. J A (Arnold) V Watson O.B.E. By kind permission of his daughter, Mrs Pamela Mainwaring Arnold Watson - Transcribed Diaries [2013.101.1] SUMMARY Capt. Watson joined the Air Transport Auxiliary in June 1940 having sought permission from his then employer Lord Wakefield (Castrol Oil). Although he held a pilot’s licence at the time, he had fewer than the minimum hours for acceptance but was accepted after a flight test. His entire time with the ATA was spent at the Headquarters at White Waltham. Initially he was ferrying, but his skills were recognised and he was later promoted to Airborne Navigation Instructor where, mainly on Oxfords & Ansons, he passed out upwards of 80 pupils, plus a few that he didn’t! However, the most important aspect of his ATA career was to come when he was asked to take over the role of Flying Technical Officer where he was responsibile for flight testing any new aircraft which the ATA were going to be asked to ferry and to provide technical information regarding the flying characteristics which would be set out in Ferry Pilots’ Notes. This involved testing the low speed characteristics of each aircraft in a wide range of weather conditions and all aspects of engine and propeller settings. From time to time, this gave cause for alarm as at times the manufacturer’s own test pilots had not tested some of these aspects. There is no doubt that Watson’s work resulted in the greater safety of many pilots. -

Name of Plan M & M 292 M & S 29 M

WING RUBBE ENGIN REDUCED DETAILS NAME OF PLAN SPAN SOURCE Price AMA POND RC FF CL OT SCALE GAS R ELECTRIC OTHER GLIDER 3 VIEW E OT M & M 292 $ - 33850 65 X M & S 29 $ - 34011 387 X L FLODSTROM 1977 64D7 M 2 A 40 $ 13 28674 X X MOTODELLO 60A6 M 30 52 $ 13 28044 X X MOCO MILANO 88G1 M 32 DINDI 35 $ 7 31861 X X X AEROMODELLER PLAN 6/36, 55C2 M 70 36 DeBOBROVSKY $ 10 26342 X X X K J HARRIS M AXE IMUS 77 $ 25 33635 X X 74A4 FLYING ACES CLUB, GROVES 57D3 M BRIO 18 $ 3 26655 X X ROY MARQUARDT 1939 7D7 X M D 9 50 $ 8 33206 X X RD300 M D 9 $ - 34876 X M E N WORLD ENGINEERING OF 83C2 35 NORWALK $ 9 33259 X X MINIMOUSTANG MODEL ENGINEERING OF 83B1 M E N PIPER CUB 72 NORWALK $ 14 33256 X X X MODEL ENGINEERING OF 84D7 M E N TRAINER 58 NORWALK $ 15 31356 X X AEROMODELLER PLAN 12/81, 75E6 M G 049 68 STROUD $ 4 29938 X X X MICHAEL GRANEIRI 1935 64C1 X M G 1 108 $ 28 28641 X X RD307 M G 2 $ - 34883 X MIKE GRANIERI X M G 2 * 51 $ 14 50013 X X MICHAEL GRANEIRI 1935 45D4 X M G 2* 48 $ 7 25132 X X MICHAEL GRANEIRI 1935 39E3 X M G* 55 $ 8 24417 X X B PILAR, CZECHOSLOVAKIA 77E4 M K M 156 METEOR 40 $ 13 30196 X X B PILAR 1947, 45C3 M K M 158 ORAN 40 CZECHOSLOVAKIA $ 13 32825 X X Z LEDVINA, POLAND 64F7 M K M 3 STANDART 27 $ 8 28712 X X WING RUBBE ENGIN REDUCED DETAILS NAME OF PLAN SPAN SOURCE Price AMA POND RC FF CL OT SCALE GAS R ELECTRIC OTHER GLIDER 3 VIEW E OT JAPANESE VERSION OF THE 81E1 X M M 12 58 WEDGY $ 14 31168 X X FLUG & MODELL TECHNIK 2/62, 31F6 M W F 36 ESPE 56 WEIST $ 7 33440 X X X FLYING MODELS BY BILL M.A.C. -

On the Early History of Spinning and Spin Research in the UK Part 3: the Period 1940 to 1949

Journal of Aeronautical History Paper 2019/05 On the early history of spinning and spin research in the UK Part 3: the period 1940 to 1949 Brian Brinkworth Waterlooville UK Abstract This third part of a study of the history of spinning and spin research in the UK covers the decade of the 1940s, which was dominated by almost five years of the Second World War. New types of aircraft were required to replace obsolete ones and to fill changing operational needs, though they were subject to essentially the same spin testing procedures as in the pre-war period. Testing with dynamic models continued in the vertical Free Spinning Tunnel at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, and at full-scale at the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment. In the later years of the war, the first squadrons of jet-propelled types were formed, followed by the appearance of aircraft with new configurations for flight in the compressible range. Although little fundamental research on spinning could be undertaken in wartime conditions, progress continued, mainly through empirical developments in the model testing methods. These included refinement of the modelling by, for example, representing the angular momentum of engines and propellers, and of the test procedures to improve the agreement between the outcome of a model test and that of the corresponding aircraft test at full-scale. These were significant advances, which were made at the expense of greater complexity in the methods employed. 1. Introduction 1.1 Spinning and recovery The development in Britain of an understanding of the spinning of aircraft and of means of recovering from spins has been reviewed previously in this journal, covering the earlier periods from 1909 to 1929 (1) and from 1930 to 1939 (2). -

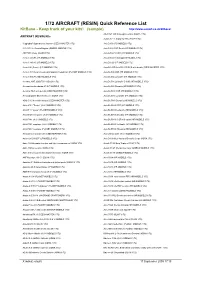

1/72 AIRCRAFT (RESIN) Quick Reference List Kitbase - Keep Track of Your Kits! (Sample)

1/72 AIRCRAFT (RESIN) Quick Reference List KitBase - Keep track of your kits! (sample) http://www.suisoft.co.uk/kitbase/ ASJA SA-14E Norwegian version (KORA 1/72) AIRCRAFT (RESIN) Kits Austin A.F.T. 3 Osprey RFC (RVHP 1/72) "Upgraded" Supermarine Attacker (CZECHMASTER 1/72) Avia B-158 (RS MODELS 1/72) A.C.A.Z.C.2. Decals Belgium (OMEGA MODELS 1/72) Avia B-534 CSR Zurich (HR MODELS 1/72) AERFER Ariette (DUJIN 1/72) Avia B-534/IV CSR (HR MODELS 1/72) Aero A.14 CSA (HR MODELS 1/72) Avia B-534/IV Schlepp (HR MODEL 1/72) Aero A.14/A.15 (HR MODELS 1/72) Avia BH-2IJ (HR MODELS 1/72) Aero A.26 (Czech) (HR MODELS 1/72) Avia BH-33E/Avia BH-33E-SHS with decals (CZECHMASTER 1/72) Aero A-101 Decals Czech and Spanish Republican (PLANET MODELS 1/72) Avia Bk.534 CSR (HR MODELS 1/72) Aero A-300 (PLANET MODELS 1/72) Avia Bk.534 Luftwaffe (HR MODELS 1/72) Aeromot AMT 200S/TG 14 (DUJIN 1/72) Avia Bk.534 Luftwaffe D-IUIG (HR MODELS 1/72) Aeronautica Lombarda AR (LF MODELS 1/72) Avia Bk.534 Slovakia (HR MODELS 1/72) Aeronca TG-5 with decals (CZECHMASTER 1/72) Avia Bk.534/I CSR (HR MODELS 1/72) Aerostatoplane Zhuschenko ex- (KORA 1/72) Avia Bk.534/I Luftwaffe (HR MODELS 1/72) AGO C.IV. Now with decals! (CZECHMASTER 1/72) Avia Bk.534/I Slovakia (HR MODELS 1/72) Aichi A1A1 "Denko" (A & V MODELS 1/72) Avia Bk.534/II CSR (HR MODELS 1/72) Aichi E 11 "Laura" (PLANET MODELS 1/72) Avia Bk.534/II Luftwaffe (HR MODELS 1/72) Aichi E12A1 seaplane (A & V MODELS 1/72) Avia Bk.534/II Slovakia (HR MODELS 1/72) Aichi F1A1 (A & V MODELS 1/72) Avia Bk.534/III CSR with spats (HR MODELS 1/72) Aichi F1A1 seaplane (A & V MODELS 1/72) Avia Bk.534/III Luftwaffe (HR MODELS 1/72) Aichi H9A1 seaplane (PLANET MODELS 1/72) Avia Bk.534/III Slovakia (HR MODELS 1/72) Albatros C.III with decals (CZECHMASTER 1/72) Avia LM-02 glider (A & V MODELS 1/72) Ambrosini SAI 207 (LF MODELS 1/72) Avia S-199 Mule National Security Corps (KORA 1/72) Anbo IVL Lithuanian bomber and light reconaissance (KORA 1/72) Aviatik 30.24 Berg Triplane (RVHP 1/72) Anbo IVM ski version (KORA 1/72) Aviatik 30.27. -

Aeroplane Photo Supply Index APS Data 1000Aircraftphotos Known Page On-Line Archive No

Index August 29, 2021 UNDER CONTINUOUS CONSTRUCTION Aeroplane Photo Supply Index APS data 1000aircraftphotos known page on-line archive no. manufacturer model registration / remarks source 4864 no. 2030 2280 √ 1 Airspeed AS.10 Oxford Mk.I L4576 1 I 22+462030 1 - 2 Armstrong WhitworthA.W.38 Whitley B.Mk.IV - 1 P - - - √ 3 Avro 652A Anson Mk.I K6159 1 P 2400 1 - √ 4 Blackburn B-6 Shark Mk.I K4352 1 P 2401 1 - √ 5 Blackburn B-24 Skua Mk.II L2883 1 I 46 2402 1 - √ 6 Blackburn B-25 Roc Mk.I L3118 1 P 2031 1 - √ 7 Boulton Paul P.82 Defiant K8310 1 P 11756 1 - √ 8 Bristol 152 Beaufort B.Mk.I L4449 c/n 8310 1 P 2824 1 - √ 9 Bristol 149 Blenheim Mk.I K7037 1 P - - 1 √ 10 Bristol 149 Blenheim Mk.IV L4859 c/n 8874 1 I 46 2032 1 - √ 11 Bristol 130 Bombay Mk.II L5808 c/n SH.1 1 P 2681 1 - √ 12 de Havilland D.H.82A Tiger Moth R5130 c/n 83012 1 P 2403 1 - √ 13 Fairey Albacore Mk.I - 1 P 2033 1 - √ 14 Fairey Battle Mk.I K7650 c/n F.2408 1 I 22+462404 1 - √ 15 Fairey Seafox Mk.I K8587 c/n F.2285 1 P - - 1 √ 16 Fairey Swordfish Mk.I K5933 c/n F.2152 1 P - - 1 √ 17 Gloster Gladiator Mk.I K6132 1 P 2405 1 - √ 18 Gloster G.38 F.5/34 K5604 1 P 10985 1 - √ 19 Handley Page H.P.52 Hampden B.Mk.I L4159 1 P 2034 1 - √ 20 Handley Page H.P.52 Hereford B.Mk.I L6003 1 P 13355 1 - √ 21 Hawker P.V.3 I-PV3 1 P 2406 1 - √ 22 Hawker Henley TT.Mk.III L3261 1 P 7747 1 - √ 23 Hawker Hurricane Mk.I N2358, P2569, P2575, et al 1 P 2035 1 - √ 24 Saunders-Roe S.36 Lerwick Mk.I L7248 1 P 2407 1 - √ 25 Short S.19 Singapore Mk.III - 1 P 2408 1 - √ 26 Short S.25 Sunderland Mk.I L2163 -

Book Reviews MILES AIRCRAFT

Afterburner Book Reviews JUNKERS F13 The World’s First All-Metal Today, only four complete original F13s are First fl own in preserved, with a fi fth being under restoration. There 1919, this small, Airliner are also plans to build two fl ying examples. By L Andersson et al There are, of course, numbers of books about six-seater, Junkers aircraft and the F13 is inevitably covered single-engined EAM Books EEIG, 3 Gatesmead, Haywards Heath to some extent and so, one may ask, is there room airliner, with RH16 1SN, UK (www.junkersf13.com). 2012. for another book on the F13? The answer is ‘yes’, its distinctive 288pp. Illustrated. £39.95 (Plus postage/packing because this book is very well researched indeed and (UK — £6, Europe — £12, Rest of the World — brings together information from a large number of corrugated £20). ISBN 978-0-9573744-0-9. contributors and sources. The authors tell us that the metal skin, was information was gathered over 40 years or more, a the fi rst aircraft Today, the Junkers F13 looks rather quaint but lengthy gestation, if not something of a record! designed its claim to fame is given in the book’s title. First The readable text (and many photos) is fl own in 1919, this small, six-seater, single-engined followed by 57 pages of production lists which specifi cally airliner, with its distinctive corrugated metal skin, are comprehensive and detailed, although the to carry was the fi rst aircraft designed specifi cally to carry authors mention that there are still questions to be passengers passengers.