Equity in Auckland's Transport System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Item 12 Attachment 1 SOI for Board July 2021

1 Auckland Transport Statement of Intent 2021/22-2023/24 2 Auckland Transport Statement of Intent 2021/22-2023/24 Table of Contents Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………..………..4 Part I: Strategic overview Roles and Responsibilities…………………………………………………………………..………6 Responses to council’s strategic objectives.…………………………………………….………...7 Nature and scope of activities……………………………………………………….……….……15 About us……………………………………………………………………………………….……..21 Part II: Statement of Performance Expectation Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………..……24 How we will deliver - annual work programme……………….…………………………..….…..53 Financial statements………………………………………………………………………….…….63 3 Auckland Transport Statement of Intent 2021/22-2023/24 Introduction The past year has been one underlined by change, requiring swift and decisive responses to an incredibly dynamic situation. The COVID-19 pandemic (COVID-19) has become a part of our day-to-day lives and will remain a source of uncertainty in the discharge of our duties and role as Auckland’s road controlling authority, and provider of public transport. Despite the challenge posed by COVID-19, Auckland Transport (AT) continued to function and support the Auckland community while keeping the health and safety of our frontline staff and customers as our utmost priority. AT’s actions and prompt messaging were recognised by the Association of Local Government Information Management (ALGIM), placing first in the exercise of leadership and innovation during COVID-19. COVID-19 has had flow-on effects, resulting in legislative change, as well as financial constraints. AT has been assisting Auckland Council (Council) in navigating the new processes introduced by the new Fast Track Consenting Act, while also continuing to focus on project delivery across the region. With a decreased and limited budget, and work further hampered by shifting COVID-19 Alert Levels in Auckland, AT learnt to operate in an uncertain climate. -

Rail Electrification and Extension from Papakura to Pukekohe Updates Glossary

Agenda Item 13 (iv) Rail Electrification and Extension from Papakura to Pukekohe Updates Glossary Auckland Council (AC) Auckland Electrified Area (AEA) Auckland Plan (AP) Auckland Transport (AT) Construcciones y Auxiliar de Ferrocarriles (CAF) Diesel Multiple Unit (DMU) Electric Multiple Unit (EMU) KiwiRail Group (KRG) New Zealand Transport Agency (NZTA) North Auckland Line (NAL) North Island Main Trunk Line (NIMT) Onehunga Branch Line (OBL) Regional Land Transport Programme (RLTP) Rapid Transit Network (RTN) Executive Summary Item 1: Auckland Rail Electrification Update AT and KRG are currently undertaking preparatory works for electrification of the Auckland Rail Network between Papakura and Swanson Stations, with the first EMU services being tested and commissioned from September 2013. The target is for EMU passenger services to be introduced from December 2013, initially on the OBL. The remainder of the EMU fleet will be introduced in stages until the full fleet is in service under current programme timelines in mid-2016. The electrification projects can be grouped as follows: a) Installation and commissioning of electrification infrastructure: overhead wires, gantries, earthing of stations, etc., primary responsibility with KRG. b) Station and depot infrastructure: preparation for electrification includes construction of an EMU depot at Wiri, upgrading of a number of existing stations to a common standard, construction of a new station at Parnell, ensuring sufficient stabling for the EMU fleet. Responsibility is primarily with AT; c) Procurement of new EMU fleet: Including operational transitioning from the existing DMU and diesel locomotives to the new EMUs. Responsibility rests with AT. d) Operational readiness for electrification: Training of staff, train drivers and contractors for working within an electrified environment, agreement on responsibility for maintaining electrification assets, agreement on safety provisions for public and contractors, communications with the public and other stakeholders. -

Learnings from a Programme Business Case Transport Networks for Growth Programme

Learnings from a Programme Business Case Transport Networks for Growth Programme 24 February 2017 Gavin Smith, BCom, MEngSt, CPEng, MIPENZ Principal Transport Planner – Strategic Growth Initiatives Auckland Transport [email protected] Craig Mitchell, BE(Hons), IntPE(NZ), CPEng, MIPENZ Principal Transport Planner – Highways and Network Operations NZ Transport Agency [email protected] Abstract Auckland is expected to grow by up to 1 million people by 20431. It is anticipated that 60-70% of this growth will occur within existing urban areas, with the remainder in future growth areas. Approximately 15,000 hectares of future growth is land that has been identified in the Proposed Auckland Unitary Plan (Operative in part) to accommodate this. The Business Case approach was used to investigate a future transport network in Auckland’s future growth areas, and deliver the planning and investment outcomes needed. By tailoring the Business Case approach the process ensured that a consistent regional approach was applied at a local level and provided enough detail and flexibility to respond to immediate and on-going development pressures within each growth area. 1 Statistics NZ high growth projections, 2013 Learnings from a Programme Business Case G.Smith, C.Mitchell Page 1 Background The Transport Networks for Growth project (previously known as Transport for Future Urban Growth) was completed in an eight month period in 2016 and is the largest and most complex Programme Business Case completed in New Zealand. The Programme Business Case identified a $7.6 billion regional programme (the Programme) covering four geographical areas (Warkworth, North, North West, South) comprising some 15,000 hectares of future growth areas land. -

Supporting Growth Delivering Transport Networks

Supporting Growth Delivering transport networks SUMMARY Supporting Growth – Delivering Transport Networks | Summary 3 The preferred network KEY AUCKLAND IS GROWING FAST WITH AN ADDITIONAL July 2016 Future Urban Zone (Potential Business) 1 July 2016 Future Urban Zone 700,000 TO 1 MILLION PEOPLE EXPECTED TO CALL (Potential Residential & Other Urban Uses) Live Zoned AUCKLAND HOME OVER THE NEXT 30 YEARS, REQUIRING Special Purpose Future Urban Zone added as a result of Council decisions on the Unitary Plan ABOUT 400,000 NEW HOMES AND 277,000 JOBS. Special Housing Area (within growth areas) Existing Urban Area State Highway As New Zealand’s largest city, Auckland is Government to improve alignment on a long-term Where will this growth go? New public transport corridor home to about a third of the nation’s population strategic approach to transport in Auckland). It has Improved road corridor and continues to be the country’s fastest also worked closely the “three waters” providers New road corridor growing region. (water supply, stormwater, wastewater) to ensure Rural, coastal Future Ferry services it is aligned with the wider regional plans being and country growth areas Rail corridor improvements While most of Auckland’s growth will take place developed for the city. living outside 2010 Rail corridor investigations within the existing urban areas, around 15,000 metropolitan Safety improvements hectares of greenfield (mainly rural) land has been The programme supports the council’s Future identified in the Auckland Unitary Plan (Operative Urban Land Supply Strategy which sets the order urban limit in part). This includes areas zoned ‘future urban’ in which land is supplied for development in (rural land zoned for future urban development), future growth areas to house Auckland’s growing 15% 25% as well rural land that has been ‘live zoned’ (zoned population as infrastructure becomes available. -

Discovering the Hindrance of Walking and Cycling in Auckland’S Urban Form

DISCOVERING THE HINDRANCE OF WALKING AND CYCLING IN AUCKLAND’S URBAN FORM. MEYER NEESON A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Urban Design at the University of Auckland, 2020. Abstract Active transport is a fundamental element in a city’s movement network that promotes a sustainable and resilient urban future, yet can only be viable in an urban setting that supports small-scale infrastructure with appropriate street environments. The 1950’s planning regimes have been dominant within Auckland’s transport development with perpetuated traditional aims of increased efficiency and high level infrastructure which enables travel in the comfort of a private vehicle. Attitudes have formulated the urban fabric through funding and investment intervention which resulted in a strong motorway network and low density, sprawling residential suburbs. Psychological public response to this environment is reflected in the heavy reliance on the private vehicle and low rates of walking and cycling. Although Auckland’s transport framework identifies the need for walking and cycling to actively form a strand of Auckland’s transport network, institutional and intellectual embedded ideas of the 1950’s prevent implementation on the ground. The failure of Auckland’s urban form was highlighted in the period of the Covid-19; post lockdown the public reverted back to old transport habits when restrictions were lifted. This pandemic put our city in the spotlight to identify its shortfalls and the urgent need to support a resilient future. Therefore, this research aims to discover the inherent infrastructure and funding barriers that hinder the growth of walking and cycling as a transport method in Auckland. -

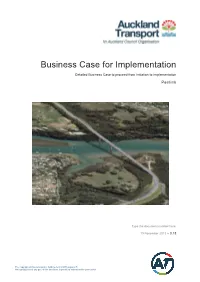

Business Case for Implementation

Business Case for Implementation Detailed Business Case to proceed from Initiation to Implementation Penlink Type the document number here. 19 November 2013 – 0.18 The copyright of this document is held by Auckland Transport. © No reproduction of any part of this document is permitted without written permission. Change History and Approval As Representative of the Executive Leadership Team (ELT), I confirm this Business Case addresses the problem or opportunity identified. An assessment of the benefits has been carried out and they are realistic and achievable. ROLE: NAME: SIGNATURE / EMAIL DATE For ELT As Senior Supplier, I endorse this Business Case. I agree the proposal is aligned with existing policy, the resource implications are noted and the estimates on cost and time are realistic and achievable. ROLE: NAME: SIGNATURE / EMAIL DATE Senior Supplier As Project Sponsor, I approve this Business Case. I confirm it is a fair and realistic representation of the opportunity, requirements and benefits. It accurately identifies resources, known risks and impacts that need to be taken into account in order to move to Project Execution phase. ROLE: NAME: SIGNATURE / EMAIL DATE Project Sponsor Revision Status REVISION NUMBER: IMPLEMENTATION DATE: SUMMARY OF REVISION 0.1 21 June 2013 First draft of Sections 3-6 by Beca 0.2 15 July 2013 PwC edits 0.3 13 August 2013 Second draft Sections 2-8 inclusive (excluding 2.3) 0.4 21 August 2013 PwC Edits 0.5 2 September 2013 Inclusion of Auckland Transport Management Section 0.6 4 September 2013 Inclusion of Beca edits to Sections 3-7 0.7 26 September 2013 Inclusion of final edits from Beca 0.8 26 September 2013 PwC Internal Review 0.9 22 October 2013 PwC Final Draft 0.14 30 October 2013 Incorporation of AT Comments DOCUMENT NAME Detailed Business Case Template v0.5 - Penlink VERSION Draft for Information – not endorsed for implementation DOCUMENT No. -

9 Attachment 1 RLTP JUNE 2021 at Board

VERSION TO AT BOARD 28 JUNE Auckland Regional Land Transport Plan 2021-2031 Auckland Regional Land Transport Plan 2021–2031 The Regional Land Transport Plan 2021-2031 sets out the land transport objectives, policies and measures for the Auckland region over the next 10 years. It includes the land transport activities of Auckland Transport, Auckland Council, Waka Kotahi NZ Transport Agency, KiwiRail, and other agencies. VERSION TO AT BOARD 28 JUNE 1 Auckland Regional Land Transport Plan 2021–2031 Contents 01. Introduction from the Chair 3 02. Context 5 03. Feedback from consultation 13 04. Purpose and scope 21 05. Transport funding 29 06. Auckland’s transport challenges 33 07. Responding to Auckland’s transport challenges 47 08. Measuring outcomes 77 09. Inter-regional priorities 85 10. Funding and expenditure 91 11. Appendices 99 VERSION TO AT BOARD 28 JUNE 2 Auckland Regional Land Transport Plan 2021–2031 01. Introduction from the Chair VERSION TO AT BOARD 28 JUNE To come 3 Introduction from the Chair Auckland Regional Land Transport Plan 2021–2031 VERSION TO AT BOARD 28 JUNE Introduction from the Chair 4 Auckland Regional Land Transport Plan 2021–2031 02. Context Auckland, Tāmaki Makaurau, is home to 1.7 million people – one third of all NewVERSION Zealanders – and TO is forecast to grow by another 260,000 overAT the BOARD next decade, reaching around 2.4 million by 2050. This 28rapid JUNE population growth presents a number of challenges in our quest to be a liveable, climate-friendly and productive city. Growth represents opportunity but Evidence tells us that Aucklanders Auckland needs a well-coordinated when combined with Auckland’s like the improved experience, and integrated approach to help challenging natural setting and particularly on rapid and frequent people and freight get around urban form the outcome has bus and train services where quickly and safely – one that been increased congestion and the number of trips has almost significantly reduces harm to the limited connectivity. -

Auckland Regional Land Transport Plan 2015-2025 Auckland Transport

18pt Auckland Regional Land Transport Plan 2015-2025 Auckland Transport Adapted in accordance with Section 69 of the Copyright Act 1994 by the Royal New Zealand Foundation of the Blind, for the sole use of persons who have a print disability. No unauthorised copying is permitted. Produced 2015 by Accessible Format Production, Blind Foundation, Auckland Total print pages: 137 Total large print pages: 315 Publishing Information This large print edition is a transcription of the following print edition: Published by Auckland Council, 6 Henderson Valley Road, Henderson, Auckland © Auckland Transport 2015 Logos represented on the publication cover: NZ Land Transport Agency, KiwiRail, Auckland Council, Auckland Transport Large Print Edition Main text is in Arial typeface, 18 point. Headings, in order of significance, are indicated as: Heading 1 Heading 2 The publisher's page numbering is indicated in text as: Page 1 Omissions and Alterations Brief descriptions have been given in the place of figures. These figures include diagrams, graphs and maps. Where the figure is made up largely of text elements (for example a flowchart), it has been transcribed in full. Map descriptions focus on the scope of the map rather than the details. Notes from the transcriber have been prefaced by "TN" (transcriber's note). Contact Auckland Transport for further Information For extended verbal descriptions of maps or for further information on the maps please call Auckland Transport, (09) 301 0101, or email [email protected]. Please make it clear your query relates to the Regional Land Transport Plan. If you email us please provide your name and a contact phone number. -

Comments from Auckland Transport

or land use proposed so that integrated transport and land use outcomes occur. Guidance is available on Auckland Transport’s website to assist in the preparation of an ITA is available, including a draft template. 4. The applicant has submitted a Traffic Impact Assessment prepared by TPC and dated February 2021, ‘Reference 20278, Issue B – Final’. Auckland Transport has previously reviewed the TIA submitted with this application as part of pre-application discussions with the applicant, and it appears that the TIA has not been updated since those discussions. A Traffic Impact Assessment has a limited scope and does not provide the level of analysis that would normally be included in an ITA. 5. Auckland Transport has reviewed the additional information supplied by the applicant, including the revised engineering drawings and the TPC letter, dated 2 June 2021, in response to the request for further information made by the Environmental Protection Agency. This review is limited given an ITA has not been provided – it is noted that an ITA would ordinarily address many of the outstanding matters identified. It is not, therefore, possible at this stage to determine whether the Project will help to achieve the purpose of the Act nor whether there is potential for the Project to have significant adverse environmental effects, including greenhouse gas emissions (Section 19 e)). 6. The following sections discuss this matter further and identify further outstanding matters or issues. Resolution of such is considered necessary in order to ensure any adverse transport effects can be avoided, remedied, and/or mitigated. Access to Public Transport 7. -

Have Your Say Changing Public Transport in South Auckland New Network Auckland Transport Private Bag 92250 West Street Victoria Auckland 1142 Freepost Authority No

Have your say Changing public transport in South Auckland New Network Auckland Transport Private Bag 92250 West Street Victoria Auckland 1142 FreePost Authority No. 233462 FreePost Find out more: 09 366 6400 or visit www.aucklandtransport.govt.nz Transforming Auckland’s public transport network Over the next few years Auckland Transport is moving to a simpler and more integrated public transport network for Auckland. How to find out more This will deliver a New Network of buses and trains that will change the way people travel – including the need for some passengers to transfer at key interchanges. In return the New Network will allow more Visit our website to view individual route maps passengers to simply ‘turn up and go’ rather than planning trips around a timetable. It will offer and suburb guides for key areas of South flexible travel options over large parts of the city, making public transport more useful for a range of Auckland, read answers to frequently asked travel purposes. questions and watch our video. This document has been translated into Maori, Tongan, Samoan, The map on page 2 shows the proposed new frequent routes for the whole of Auckland. This Frequent Korean, Hindi, Punjabi and Chinese and is Network will have trains and buses timetabled at least every 15 minutes from 7am to 7pm, seven days available on our website. We are also holding a week. They will be supported by a network of Connector routes timetabled at least every 30 minutes Open Days near you and encourage you to along with Local and Peak services, to ensure Aucklanders continue to have access to public transport and come along. -

Shared Mobility Simulations for Auckland

CPB Corporate Partnership Board Shared Mobility Simulations for Auckland Case-Specific Policy Analysis Shared Mobility Simulations for Auckland Case-Specific Policy Analysis The International Transport Forum The International Transport Forum is an intergovernmental organisation with 59 member countries. It acts as a think tank for transport policy and organises the Annual Summit of transport ministers. ITF is the only global body that covers all transport modes. The ITF is politically autonomous and administratively integrated with the OECD. The ITF works for transport policies that improve peoples’ lives. Our mission is to foster a deeper understanding of the role of transport in economic growth, environmental sustainability and social inclusion and to raise the public profile of transport policy. The ITF organises global dialogue for better transport. We act as a platform for discussion and pre-negotiation of policy issues across all transport modes. We analyse trends, share knowledge and promote exchange among transport decision-makers and civil society. The ITF’s Annual Summit is the world’s largest gathering of transport ministers and the leading global platform for dialogue on transport policy. The Members of the ITF are: Albania, Armenia, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, China (People’s Republic of), Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, India, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Korea, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, Republic of Moldova, Montenegro, Morocco, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom and the United States. -

05 Auckland Transport

# 05 20 Viaduct Harbour Avenue, Auckland 1010 Private Bag 92250, Auckland 1142, New Zealand Phone 09 355 3553 Website www.AT.govt.nz 10 August 2021 Attention: Planning Technician Auckland Council Level 24, 135 Albert Street Private Bag 92300 Auckland 1142 Email: [email protected] Dear Sir / Madam NOTICE OF REQUIREMENT BY CITY RAIL LINK LIMITED FOR ALTERATION OF BRITOMART TRANSPORT CENTRE DESIGNATION 2501 Please find attached Auckland Transport’s submission on the above Notice of Requirement by City Rail Link Limited. If you have any queries in relation to this submission, please contact Teresa George on 09 448 7275 or [email protected]. Teresa George Senior Planner, Land Use Policy and Planning (Central) Encl: Auckland Transport’s submission on Notice of Requirement for the alteration to the existing Britomart Transport Centre Designation 2501 Cc: City Rail Link Limited PO Box 9681 Newmarket Auckland 1149 Attention: Richard Jenkins, CRL Principal Planner Email: [email protected] 1 of 19 # 05 SUBMISSION BY AUCKLAND TRANSPORT ON A NOTICE OF REQUIREMENT BY CITY RAIL LINK LIMITED FOR ALTERATION OF BRITOMART TRANSPORT CENTRE DESIGNATION 2501 To: Auckland Council – Plans and Places Private Bag 923000 Auckland 1142 Submission on: Alteration to Designation 2501 Britomart Transport Centre by City Rail Link Limited to enable the retention of the Station Plaza Accommodation at Britomart so the building and surrounding Station Plaza area can be used as a construction support facility for works in the City Rail Link tunnels located within the adjoining designation, with the identification of the construction support activity components.