Period of Recognition Part 1 Constantine's Basilicas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Neonian Baptistery in Ravenna 359

Ritual and ReconstructedMeaning: The Neonian Baptisteryin Ravenna Annabel Jane Wharton The pre-modern work of art, which gained authority through its extension in ritual action, could function as a social integrator. This essay investigates the figural decoration of the Orthodox Baptistery in Ravenna, in an effort to explain certain features of the mosaic program. If the initiation ritual is reenacted and the civic centrality of the rite and its executant, the bishop, is restored, the apparent "icon- ographic mistakes" in the mosaics reveal themselves as signs of the mimetic re- sponsiveness of the icon. By acknowledging their unmediated character, it may be possible to re-empower both pre-modern images and our own interpretative strategy. The Neonian (or "Orthodox") Baptistery in Ravenna is the preciated, despite the sizable secondary literature generated most impressive baptistery to survive from the Early Chris- by the monument. Because the artistic achievement of the tian period (Figs. 1-5).1 It is a construction of the late fourth Neonian Baptistery lies in its eloquent embodiment of a or early fifth century, set to the north of the basilican ca- new participatory functioning of art, a deeper comprehen- thedral of Bishop Ursus (3897-96?) (Fig. 1).2 The whole of sion of the monument is possible only through a more thor- the ecclesiastical complex, including both the five-aisled ba- ough understanding of its liturgical and social context. The silica and the niched, octagonal baptistery, appears to have first section of this essay therefore attempts to reconstruct been modeled after a similar complex built in the late fourth the baptismal liturgy as it may have taken place in the century in Milan.3 Within two or three generations of its Neonian Baptistery. -

Byzantine Art and Architecture

Byzantine Art and Architecture Thesis The development of early Christian religion had a significant impact on western art after the fall of the Roman Empire in the 4th century (AD). Through examining various works of art and architecture, it becomes evident that the period of Byzantium marked a significant transition in aesthetic conventions which had a previous focus on Roman elements. As this research entails, the period of Byzantium acted as a link between the periods of Antiquity and the Middle Ages and thus provides insight on the impact of Christianity and its prevalence in art and architecture during this vast historical period. Sources/Limitations of Study Primary Sources: Adams, Laurie Schneider. Art Across Time. McGrawHill: New York, 2007. Figures: 8.4 Early Christian sarcophagus, Santa Maria Antiqua, Rome, 4th century. Marble. 8.5 Plan of Old Saint Peter’s basilica, Rome, 333390. 8.6 Reconstruction diagram of the nave of Old Saint Peter’s Basilica. 8.12 Exterior of the mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna, c. 425426. 8.13 Interior of the mausoleum of Galla Placidia showing niche with two apostles (above) and the Saint Lawrence mosaic (below), Ravenna, c. 425426. 8.14 Christ as the Good Shepherd, the mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna, c. 425 426. Mosaic. 8.28 Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (now Instanbul), illuminated at night, completed 537. 8.29 Plan, section, and axonometric projection of Hagia Sophia. 8.30 View of the interior of Hagia Sophia after its conversion to a mosque. Colour lithograph by Louis Haghe, from an original drawing by Chevalier Caspar Fussati. -

Period of Recognition Part 1 Constantine's Basilicas

The Period of Recognition AD 313—476 Surely one of the most important events in history must be the so called Edict of Milan (313), a concordat really, between Constantine in the 2 Western half of the Empire and his co-emperor in the East, Licinius, that recognized all existing religions in the Roman Empire at the time, most especially Christianity, and extended to all of them the freedom of open, public practice. Equally important, subsequently, was Constantine’s pri- vate, yet imperial, patronage of the Christian church. Also, sixty years later, in 390, the emperor Theodosius would declare Christianity the offi- cial religion of the Roman Empire and followers of the ancient pagan rites, criminals. The pagans were soon subjected to the same repression as Christians had been, save violent widespread persecution. The perse- cuted had become the persecutors . Within another hundred years (in 476) the political Empire in the West would collapse and the Christian church would become the sole unifying cultural force among a collection of bar- barian kingdoms. Christianity would go on to dominate the society of Western Europe for the next thousand years. Thus the three sources from which modern Europe sprang were tapped: Greece, Rome, and Christian- ity. Constantine’s Christianity Constantine attributed his defeat of rival Maxentius for the emperorship of the Roman Empire in the 63 The Battle at the Milvian West to the God of the Chris- Bridge tians. He had had a dream or <www.heritage-history.com/www/ heritage.php?R_m... > vision in which his mother’s Christian God told him that he would be victorious if he marched his army under the Christian symbol of the chi rho , the monogram for the name of Jesus Christ. -

Martyred for the Church

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament · 2. Reihe Herausgeber / Editor Jörg Frey (Zürich) Mitherausgeber/Associate Editors Markus Bockmuehl (Oxford) · James A. Kelhoffer (Uppsala) Tobias Nicklas (Regensburg) · J. Ross Wagner (Durham, NC) 471 Justin Buol Martyred for the Church Memorializations of the Effective Deaths of Bishop Martyrs in the Second Century CE Mohr Siebeck Justin Buol, born 1983; 2005 BA in Biblical and Theological Studies, Bethel University; 2007 MA in New Testament, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School; 2009 MA in Classical and Near Eastern Studies, University of Minnesota; 2017 PhD in Christianity and Judaism in Antiquity, University of Notre Dame; currently an adjunct professor at Bethel University. ISBN 978-3-16-156389-8 / eISBN 978-3-16-156390-4 DOI 10.1628/978-3-16-156390-4 ISSN 0340-9570 / eISSN 2568-7484 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament, 2. Reihe) The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Mohr Siebeck Tübingen, Germany. www.mohrsiebeck.com This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to repro- ductions, translations and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed by Laupp & Göbel in Gomaringen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Nädele in Nehren. Printed in Germany. Preface This monograph represents a revised version of my doctoral dissertation. It has been updated to take into account additional scholarly literature, bring in new argumentation, and shorten some sections for relevance. -

Philology and Martyrdom: a New Edition of Martyrium Polycarpi and Martyrium Pionii

Histos 9 (2015) cxxxv–cxl REVIEW PHILOLOGY AND MARTYRDOM: A NEW EDITION OF MARTYRIUM POLYCARPI AND MARTYRIUM PIONII Otto Zwierlein, Die Urfassungen der Martyria Polycarpi et Pionii und das Corpus Poly- carpianum. Band 1: Editiones criticae. Band 2: Textgeschichte und Rekonstruktion. Polykarp, Ignatius und der Redaktor Ps.-Pionius. Untersuchungen zur antiken Liter- atur und Geschichte 116.1–116.2. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2014. Pp. xx + 194; xii + 425. Hardback, €149.95. ISBN 978-3-11-037100-0. t takes a brave soul to dig for the original version of a martyr text com- posed in the mid-second century AD and adapted constantly throughout Ithe centuries to fit different political and theological needs. The account of the trial and execution at Smyrna of the Christian bishop Polycarp, first committed to writing in a letter from members of his congregation, became immediately popular as a model of correct behaviour in the face of persecu- tion. It consequently suffered greatly at the hands of unscrupulous ancient ed- itors, causing much scholarly debate about its many intractable problems. To restore the text to its pristine form, therefore, it is not enough to be courageous: a clearly defined sense of what is being looked for is also indispensible, and this is possible only with a thorough knowledge of the text’s transmission and the periods through which it was transmitted—not only their complex intellectual history, but a wide range of literatures, languages, and cultures. Otto Zwier- lein’s two-volume edition of the Martyrium Polycarpi (MPol) and the third-cen- tury Martyrium Pionii (MPion), with extensive discussion of texts and contexts, leaves no doubt that he is one of a very small number of scholars equal to the challenge. -

What Temples Stood For

WHAT TEMPLES STOOD FOR: CONSTANTINE, EUSEBIUS, AND ROMAN IMPERIAL PRACTICE BY STEVEN J. LARSON B.S., PURDUE UNIVERSITY, 1987 B.A., UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA, 1992 M.T.S., HARVARD UNIVERSITY DIVINITY SCHOOL, 1997 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES AT BROWN UNIVERSITY PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2008 © Copyright 2008 by Steven J. Larson VITA !"#$%"&'()"*)"!)+*$)$,'-*%."!)+*$)$"')"/$)0$(1"23."24567"!"8'9,-:;:+"$"&$8<:-'(=%" degree in Industrial Engineering at Purdue University in 1987. Following this, I worked as an engineer at Cardiac Pacemaker, Inc. in St. Paul, Minnesota. I left this position to pursue studies in the Humanities at the University of Minnesota. There I studied modern $(;"$)+">'+:()"?(::@"80-;0(:"$)+"-$)A0$A:"$)+"A($+0$;:+"#*;<"$"&$8<:-'(=%"+:A(::"*)"B(;" History from the Minneapolis campus in 1992. During this period I spent two summers studying in Greece. I stayed on in Minneapolis to begin coursework in ancient Latin and Greek and the major world religions. Moving to Somerville, Massachusetts I completed a 9$%;:(=%"+:A(::"$;"C$(D$(+"E)*D:(%*;1"F*D*)*;1"G8<''-"*)"244H"0)+:r the direction of Helmut Koester. My focus was on the history of early Christianity. While there I worked $%"$)":+*;'(*$-"$%%*%;$);"I'(";<:"%8<''-=%"$8$+:9*8"J'0()$-."Harvard Theological Review, as well as Archaeological Resources for New Testament Studies. In addition, I ,$(;*8*,$;:+"*)"K('I:%%'(%"L':%;:("$)+"F$D*+">*;;:)=%"MB(8<$:'-'A1"$)+";<:"N:#" O:%;$9:);P"8'0(%:.";($D:--*)A";'"%*;:%";<('0A<'0;"?(::8:"$)+"O0(@:17"O<$;"I$--."!"&:A$)" doctoral studies at Brown University in the Religious Studies departmen;"$%"$"F:$)=%" Fellow. -

The Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem and St Sophia of Constantinople: an Attempt at Discovering a Hagiographic Expression of the Byzantine Encaenia Feast

Other Patristic Studies Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 10:24:12PM via free access . Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 10:24:12PM via free access Ekaterina Kovalchuk Leuven, Belgium [email protected] THE HOLY SEPULCHRE OF JERUSALEM AND ST SOPHIA OF CONSTANTINOPLE: AN ATTEMPT AT DISCOVERING A HAGIOGRAPHIC EXPRESSION OF THE BYZANTINE ENCAENIA FEAST Constantine the Great and the Foundation of the Holy Sepulchre For a student of Late Antiquity and Byzantine civilization, Con- stantine the Great is known, fi rst and foremost, as the ruler who intro- duced Christianity as an offi cial religion of the Roman Empire. Apart from that, his name is fi rmly associated with the foundation of the eponymous city of Constantinople, which was to become a centre of the Eastern Christian civilization. A closer look at the contemporary sources, however, suggests that the fi rst Christian Emperor did not give the newly-founded city of Constantinople priority in his policies and building projects. During his reign, Constantine the Great dis- played extraordinary interest in Jerusalem, leaving Constantinople rather overshadowed. One may puzzle why Eusebius, who is the main contemporary source for the reign of Constantine the Great, gave but cursory treatment to the foundation and dedication of Constantinople while dwelling upon the subject of Palestinian church-building — and especially the foundation and dedication of the Holy Sepulchre church in Jerusalem1 — so exten- (1) The Holy Sepulchre is a later name for the complex erected by Con- stantine at the allegedly historical places of Golgotha and the tomb where Christ was buried. -

Revista Principe De Viana

The survival of early christian symbols in 12th Century Spain RUTH BARTAL* he wide distribution of the Chrismon (or the monogram of Christ) in the monumental art of Spain and the Beam region of the eleventh to the late Tthirteenth centuries is an interesting phenomenon which has not escaped scho- larly notice. Alain Sene, S. H. Caldwell and Constant Lacoste interpret the pre- sentation of the Chrismon in Spain as a symbol of the Trinity, The Passion of Christ and his triumph over death1. The study of these works is essential for an understanding of the complex religious significance of the monogram in Spa- nish Romanesque art. However, I shall attempt to take the inquiry a step fur- ther, and to consider why this symbol, one of the most evident in the early Christian era between the fourth and sixth centuries, lost its importance in Christian Europe, where it almost entirely disappeared, yet continued to appear in Spain in all periods with especial frequency from the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries. The Chrismon signifies the Tninity, or, according to a broader interpreta- tion, the Passion, the Victory over Death, and the Resurrrection. These dogmas were sacred for all Christianity, and if their representation were the only cause of the wide occurrence of the symbol in Spanish art, it would be difficult to un- derstand why it disappeared from other Christian countries. * History of Art Department, Tel Aviv University 1. ALAIN SENE, Quelques remarques sur les tympans romans a chrisme en Aragón et en Nava- rre: Melanges offerts a Rene Crozet I Poitiers 1966, pp. -

Lecture 25 6.2 Byzantine :: the Dome As an Act of Faith 1

2020-04-01 - Lecture 25 6.2 Byzantine :: The Dome as an Act of Faith 1) Constantine and Constantinople • Constantine moves capital of Roman Empire to Byzantium and it’s renamed Constantinople in 330 • Very strategic land-bridge between Asia and Europe, through which a slender body of water called the Bosporus Straight connects the Mediterranean Sea (Sea of Marmara) with the Black Sea • At the junction of the Bosporus Straight and the Sea of Marmara is a penninsula where the Greeks built Byzantium, Constantine renamed it Constantinople, and later, the Ottoman Turks renamed it Istanbul • Constantine’s architectural patronage is important, as is the fact he founded his capital there • Due to its being crowded, and built mainly built of timber Constantinople was prone to earthquakes and fire. As the city constantly rebuilt itself, its urban fabric became dense and chaotic with interspersed monuments… hence the adjective developed as a figure of speech byzantine. 2) Under Constantine’s rule, three important church-related building types emerge: • basilica type - although we’ve seen it earlier, Constantine uses this form as an imperial hall. Essentially a linear three or five aisled form, higher in the central nave with clerestory lighting, and with an apse end where Constantine’s throne would be (later as a church form the important apse would be where the priest’s altar would be. • central plan church - the nave of the church and the transept (which cross at 90º making the crossing) are of equal length, creating great emphasis on the centralized crossing where the altar would be and where a dome or tower would be - a.k.a. -

St. Polycarp of Smyrna: Bishop, Martyr, and Teacher of Apostolic Tradition

Saint Polycarp: Bishop, Martyr, and Teacher of Apostolic Tradition Saint Polycarp: Bishop of Smyrna and Holy Martyr Image courtesy of Holy Transfiguration Monastery Icons Presented by: Brian Ephrem Fitzgerald, Ph.D. At St. Philip’s Antiochian Orthodox Church, Souderton, PA 3, 10, 17 June & 1 July 2006 Saint Polycarp: Bishop, Martyr, and Teacher of Apostolic Tradition Who was Saint Polycarp of Smyrna? Saint Polycarp, Bishop of Smyrna and Holy Martyr (c. 69 - c. 156), is one of the Apostolic Fathers of the Church, namely one of the early witnesses and teachers of the Apostolic traditions of the Christian Church. As a witness, he led a life of heartfelt purity ending his earthly sojourn as a faithful martyr to his Lord. The narrative of his martyrdom, the Martyrium Sancti Polycarpi, is the first Christian narrative of a martyrdom outside of the New Testament. As a teacher, he was less a formal theologian and more of a diligent transmitter of the Apostolic traditions which he had received. The composers of the Martyrium clearly understood St. Polycarp to be a teacher faithful to the traditions received from his apostolic for- bears. St. Polycarp clearly understood himself as one who would faithfully pass on to following genera- tions what he himself had received at the feet of the Apostles. Although he does not say this overtly, this self-understanding seems apparent in his Epistle to the Philippians, his only surviving work. These two brief works, the Epistle to the Philippians, and the Martyrium Sancti Polycarpi, are the primary sources concerning this remarkable saint and martyr and are therefore the foci of this study.1 His Life Little is known about the details of St. -

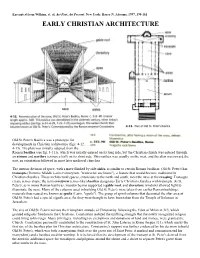

Early Christian Architecture

Excerpted from Wilkins, et. al, Art Past, Art Present. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1997, 190-161 EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE Old St. Peter's Basilica was a prototype for developments in Christian architecture (figs. 4-12, 4-13). The plan was initially adapted from the Roman basilica (see fig. 3-111), which was usually entered on its long side, but the Christian church was entered through an atrium and narthex (entrance hall) on its short side. This narthex was usually on the west, and the altar was toward the east, an orientation followed in most later medieval churches. The interior division of space, with a nave flanked by side aisles, is similar to certain Roman basilicas. Old St. Peter's has transepts (from the Middle Latin transseptum, "transverse enclosure"), a feature that would become traditional in Christian churches. These architectural spaces, extensions to the north and south, meet the nave at the crossing. Transepts create across shape; the term cruciform (cross-like) basilica designates Early Christian churches with transepts. At St. Peter's, as in many Roman basilicas, wooden beams supported a gable roof, and clerestory windows allowed light to illuminate the nave. Many of the columns used in building Old St. Peter's were taken from earlier Roman buildings; materials thus reused are known as spolia (Latin, "spoils"). The group of spiral columns that decorated the altar area at Old St. Peter's had a special significance, for they were thought to have been taken from the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. The size of Old St. Peter's mirrors the triumphant attitude of Christianity following the Edict of Milan in 313, which granted religious freedom to the Christians. -

The Life of Constantine, Oration of Constantine To

The Life of Constantine with Orations of Constantine and Eusebius. THE LIFE OF CONSTANTINE, By EUSEBIUS, 405 TOGETHER WITH THE ORATION OF CONSTANTINE TO THE ASSEMBLY OF THE SAINTS, AND THE ORATION OF EUSEBIUS IN PRAISE OF CONSTANTINE. A Revised Translation, with Prolegomena and Notes, by ERNEST CUSHING RICHARDSON, PH.D. LIBRARIAN AND ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR IN HARTFORD THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY. 1040 Preface. Preface. ———————————— 408 In accordance with the instruction of the editor-in-chief the following work consists of a revision of the Bagster translation of Eusebius’ “Life of Constantine,” Constantine’s “Oration to the Saints,” and Eusebius’ “Oration in Praise of Constantine,” with somewhat extended Prolegomena and limited notes, especial attention being given in the Prolegomena to a study of the Character of Constantine. In the work of revision care has been taken so far as possible not to destroy the style of the original translator, which though somewhat inflated and verbose, represents perhaps all the better, the corresponding styles of both Eu- sebius and Constantine, but the number of changes really required has been considerable, and has caused here and there a break in style in the translation, whose chief merit is that it presents in smooth, well-rounded phrase the generalized idea of a sentence. The work on the Prolegomena has been done as thoroughly and originally as circumstances would permit, and has aimed to present material in such way that the general student might get a survey of the man Constantine; and the various problems and discussions of which he is center. It is impossible to return special thanks to all who have given special facilities for work, but the peculiar kindness of various helpers in the Bibliothèque de la Ville at Lyons demands at least the recognition of individualized thanksgiving.