Koffiefontein HIA.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Department of Home Affairs [State of the Provinces:]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4825/department-of-home-affairs-state-of-the-provinces-104825.webp)

Department of Home Affairs [State of the Provinces:]

Highly Confidential Home Affairs Portfolio Committee PROVINCIAL MANAGER’S PRESENTATION BONAKELE MAYEKISO FREE STATE PROVINCE 6th SEPT 2011 Highly Confidential CONTENTS PART 1 Provincial Profile Provincial Management – Organogram Free State Home Affairs Footprint Provincial Capacity – Filled and Unfilled Posts Service Delivery Channels – Improving Access Corruption Prevention and Prosecution Provincial Finances – Budget, Expenditure and Assets PART 2 Strategic Overview Free State Turn-Around Times Conclusions 2 Highly Confidential What is unique about the Free State Free state is centrally situated among the eight provinces. It is bordered by six provinces and Lesotho, with the exclusion of Limpopo and Western Cape. Economic ¾ Contribute 5.5% of the economy of SA ¾ Average economic growth rate of 2% ¾ Largest harvest of maize and grain in the country. Politics ¾ ANC occupies the largest number of seats in the legislature Followed by the DA and COPE Safety and security ¾ The safest province in the country 3 Highly Confidential PROVINCIAL PROFILE The DHA offices are well spread in the province which makes it easy for the people of the province to access our services. New offices has been opened and gives a better image of the department. Municipalities has provided some permanent service points for free. 4 Highly Confidential PROVINCIAL MANAGEMENT AND GOVERNANCE OPERATING MODEL 5 Highly Confidential Department of Home Affairs Republic of South Africa DHA FOOTPRINT PRESENTLY– FREE STATE Regional office District office 6 -

Botshabelo and Thaba Nchu CRDP

Kopanong Ward # 41602001 Comprehensive Rural Development Program Status Quo Report CHIEF DIRECTORATE: SPATIAL PLANNING AND INFORMATION July 25, 2011 Authored by: SPI Free State TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 3 1.2. OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY ........................................................................................... 3 1.3. BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................ 3 2. RESEARCH DESIGN ..................................................................................................... 4 2.1. PROBLEM STATEMENT ....................................................................................... 4 2.2. METHODOLOGY .............................................................................................. 5 2.2.1. DEFINITION OF RURAL AREAS (OECD) ............................................................... 7 3. STUDY AREA .............................................................................................................. 8 3.1. PROVINCIAL CONTEXT ...................................................................................... 8 3.2. DISTRICT CONTEXT .......................................................................................... 9 3.3. LOCAL CONTEXT ........................................................................................... 10 3.4. PILOT SITE .................................................................................................. -

Death by Smallpox in 18Th and 19Th C. South Africa

Anistoriton Journal, vol. 11 (2007) Essay Section Death by smallpox investigating the relationship between anaemia and viruses in 18th and 19th century South Africa Tanya R. Peckmann, Ph.D. Saint Mary's University, Canada The historical record combined with the presence of large numbers of individuals exhibiting skeletal responses to anaemia (porotic hyperostosis and cribra orbitalia; PH and CO) are the main reasons for investigating the presence of smallpox in three South African communities, Griqua, Khoe, and ‘Black’ African, during the 18th and 19th centuries. The smallpox virus (variola) raged throughout South Africa every twenty or thirty years during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and was responsible for the destruction of entire communities. It has an 80 to 90 per cent fatality rate among non-immune populations (Aufderheide & Rodríguez-Martín 1998; Young 1998) and all ages are susceptible. The variola virus can only survive in densely populated areas and therefore sedentary communities, such as those present in agricultural and pastoral based societies, are more susceptible to acquiring the disease. Smallpox may remodel bone in the form of osteomyelitis variolosa (‘smallpox arthritis’) (Aufderheide & Rodríguez-Martín 1998; Jackes 1983; Ortner & Putschar 1985) which causes the reduction of longitudinal bone growth (Jackes 1983). However, since smallpox only remodels bone in very few individuals and solely in children the only method for unconditionally determining the presence of the smallpox virus in a skeletal population is by performing DNA and PCR analyses. Survival from smallpox affords the individual natural immunity for the remainder of their life. The virus is undetectable in a smallpox survivor as they will possess the antibodies for the disease and therefore will have gained natural immunity for the remainder of his or her life. -

Early History of South Africa

THE EARLY HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES . .3 SOUTH AFRICA: THE EARLY INHABITANTS . .5 THE KHOISAN . .6 The San (Bushmen) . .6 The Khoikhoi (Hottentots) . .8 BLACK SETTLEMENT . .9 THE NGUNI . .9 The Xhosa . .10 The Zulu . .11 The Ndebele . .12 The Swazi . .13 THE SOTHO . .13 The Western Sotho . .14 The Southern Sotho . .14 The Northern Sotho (Bapedi) . .14 THE VENDA . .15 THE MASHANGANA-TSONGA . .15 THE MFECANE/DIFAQANE (Total war) Dingiswayo . .16 Shaka . .16 Dingane . .18 Mzilikazi . .19 Soshangane . .20 Mmantatise . .21 Sikonyela . .21 Moshweshwe . .22 Consequences of the Mfecane/Difaqane . .23 Page 1 EUROPEAN INTERESTS The Portuguese . .24 The British . .24 The Dutch . .25 The French . .25 THE SLAVES . .22 THE TREKBOERS (MIGRATING FARMERS) . .27 EUROPEAN OCCUPATIONS OF THE CAPE British Occupation (1795 - 1803) . .29 Batavian rule 1803 - 1806 . .29 Second British Occupation: 1806 . .31 British Governors . .32 Slagtersnek Rebellion . .32 The British Settlers 1820 . .32 THE GREAT TREK Causes of the Great Trek . .34 Different Trek groups . .35 Trichardt and Van Rensburg . .35 Andries Hendrik Potgieter . .35 Gerrit Maritz . .36 Piet Retief . .36 Piet Uys . .36 Voortrekkers in Zululand and Natal . .37 Voortrekker settlement in the Transvaal . .38 Voortrekker settlement in the Orange Free State . .39 THE DISCOVERY OF DIAMONDS AND GOLD . .41 Page 2 EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES Humankind had its earliest origins in Africa The introduction of iron changed the African and the story of life in South Africa has continent irrevocably and was a large step proven to be a micro-study of life on the forwards in the development of the people. -

Thesis Hum 2007 Mcdonald J.Pdf

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town 'When Shall These Dry Bones Live?' Interactions between the London Missionary Society and the San Along the Cape's North-Eastern Frontier, 1790-1833. Jared McDonald MCDJAR001 A dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in Historical Studies Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town 2007 University of Cape Town COMPULSORY DECLARATION This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature:_fu""""',_..,"<_l_'"'"-_(......\b __ ~_L ___ _ Date: 7 September 2007 "And the Lord said to me, Prophe,\y to these bones, and scry to them, o dry bones. hear the Word ofthe Lord!" Ezekiel 37:4 Town "The Bushmen have remained in greater numbers at this station ... They attend regularly to hear the Word of God but as yet none have experiencedCape the saving effects ofthe Gospe/. When shall these dry bones oflive? Lord thou knowest. -

Xhariep Magisterial District

!. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. XXhhaarriieepp MMaaggiisstteerriiaall DDiissttrriicctt !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. TheunissenS ubD istrict !. BARKLY WEST R59 R707 !. ST DEALESVILLE R708 SAPS WINBURG ST R70 !. R370 Lejwelepuitsa SAPS Dealesville R73 Winburg ST ST ST R31 Lejwelepuitsa ST Marquard !. ST LKN12 Boshof !. BRANDFORT Brandfort SAPS !. Soutpan R703 SAPS !. R64 STR64 Magiisteriiall R703 !. ST Sub District Marquard Senekal CAMPBELL ST Kimberley Dealesville ST Ficksburg !. !. !. !. R64 Sub BOSHOF SOUTPAN SAPS KIMBERLEY ST Sub !. !. !. SAPS Diistriict R64 SAPS Brandfort !. SAPS ST R709 Sub District District Sub !. !. Sub ST District Verkeerdevlei MARQUARD Sub District N1 !. SAPS Clocolan !. !. District STR700 KL District -

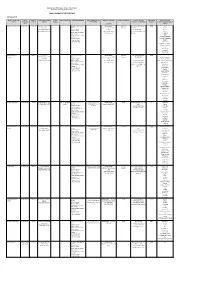

Public Libraries in the Free State

Department of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation Directorate Library and Archive Services PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE FREE STATE MOTHEO DISTRICT NAME OF FRONTLINE TYPE OF LEVEL OF TOWN/STREET/STREET STAND GPS COORDINATES SERVICES RENDERED SPECIAL SERVICES AND SERVICE STANDARDS POPULATION SERVED CONTACT DETAILS REGISTERED PERIODICALS AND OFFICE FRONTLINE SERVICE NUMBER NUMBER PROGRAMMES CENTER/OFFICE MANAGER MEMBERS NEWSPAPERS AVAILABLE IN OFFICE LIBRARY: (CHARTER) Bainsvlei Public Library Public Library Library Boerneef Street, P O Information and Reference Library hours: 446 142 Ms K Niewoudt Tel: (051) 5525 Car SA Box 37352, Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 446-3180 Fair Lady LANGENHOVENPARK, Outreach Services 17:00 Fax: (051) 446-1997 Finesse BLOEMFONTEIN, 9330 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 karien.nieuwoudt@mangau Hoezit Government Info Services Sat: 8:30-12:00 ng.co.za Huisgenoot Study Facilities Prescribed books of tertiary Idees Institutions Landbouweekblad Computer Services: National Geographic Internet Access Rapport Word Processing Rooi Rose SA Garden and Home SA Sports Illustrated Sarie The New Age Volksblad Your Family Bloemfontein City Public Library Library c/o 64 Charles Information and Reference Library hours: 443 142 Ms Mpumie Mnyanda 6489 Library Street/West Burger St, P Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 051 405 8583 Africa Geographic O Box 1029, Outreach Services 17:00 Architect and Builder BLOEMFONTEIN, 9300 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 Tel: (051) 405-8583 Better Homes and Garden n Government Info -

Federal Register/Vol. 74, No. 142/Monday, July 27, 2009/Notices

37000 Federal Register / Vol. 74, No. 142 / Monday, July 27, 2009 / Notices Africa from which citrus fruit is Inspection Service has determined the contact Dr. Patricia L. Foley, Center for authorized for importation into the regulatory review period for NAHVAX® Veterinary Biologics, Policy Evaluation United States, our review of the Marek’s Disease Vaccine and is and Licensing, VS, APHIS, 510 South information presented by the Republic publishing this notice of that 17th Street, Suite 104, Ames, IA 50010; of South Africa in support of its request determination as required by law. We phone (515) 232–5785, fax (515) 232– is examined in a commodity import have made this determination in 7120. evaluation document (CIED) titled response to the submission of an SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The ‘‘Recognition of Additional Magisterial application to the Commissioner of provisions of 35 U.S.C. 156, ’’ Extension Districts as Citrus Black Spot Pest-Free Patents and Trademarks, Department of of patent term,’’ provide, generally, that Areas for the Republic of South Africa.’’ Commerce, for the extension of a patent a patent for a product may be extended The CIED may be viewed on the that claims that veterinary biologic. for a period of up to 5 years as long as Regulations.gov Web site or in our DATES: We will consider all requests for the patent claims a product that, among reading room (see ADDRESSES above for revision of the regulatory review period instructions for accessing other things, was subject to a regulatory determination that we receive on or review period before its commercial Regulations.gov and information on the before August 26, 2009. -

Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment

Study Name: Orange River Integrated Water Resources Management Plan Report Title: Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment Submitted By: WRP Consulting Engineers, Jeffares and Green, Sechaba Consulting, WCE Pty Ltd, Water Surveys Botswana (Pty) Ltd Authors: A Jeleni, H Mare Date of Issue: November 2007 Distribution: Botswana: DWA: 2 copies (Katai, Setloboko) Lesotho: Commissioner of Water: 2 copies (Ramosoeu, Nthathakane) Namibia: MAWRD: 2 copies (Amakali) South Africa: DWAF: 2 copies (Pyke, van Niekerk) GTZ: 2 copies (Vogel, Mpho) Reports: Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment Review of Surface Hydrology in the Orange River Catchment Flood Management Evaluation of the Orange River Review of Groundwater Resources in the Orange River Catchment Environmental Considerations Pertaining to the Orange River Summary of Water Requirements from the Orange River Water Quality in the Orange River Demographic and Economic Activity in the four Orange Basin States Current Analytical Methods and Technical Capacity of the four Orange Basin States Institutional Structures in the four Orange Basin States Legislation and Legal Issues Surrounding the Orange River Catchment Summary Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 General ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Objective of the study ................................................................................................ -

South Africa)

FREE STATE PROFILE (South Africa) Lochner Marais University of the Free State Bloemfontein, SA OECD Roundtable on Higher Education in Regional and City Development, 16 September 2010 [email protected] 1 Map 4.7: Areas with development potential in the Free State, 2006 Mining SASOLBURG Location PARYS DENEYSVILLE ORANJEVILLE VREDEFORT VILLIERS FREE STATE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT VILJOENSKROON KOPPIES CORNELIA HEILBRON FRANKFORT BOTHAVILLE Legend VREDE Towns EDENVILLE TWEELING Limited Combined Potential KROONSTAD Int PETRUS STEYN MEMEL ALLANRIDGE REITZ Below Average Combined Potential HOOPSTAD WESSELSBRON WARDEN ODENDAALSRUS Agric LINDLEY STEYNSRUST Above Average Combined Potential WELKOM HENNENMAN ARLINGTON VENTERSBURG HERTZOGVILLE VIRGINIA High Combined Potential BETHLEHEM Local municipality BULTFONTEIN HARRISMITH THEUNISSEN PAUL ROUX KESTELL SENEKAL PovertyLimited Combined Potential WINBURG ROSENDAL CLARENS PHUTHADITJHABA BOSHOF Below Average Combined Potential FOURIESBURG DEALESVILLE BRANDFORT MARQUARD nodeAbove Average Combined Potential SOUTPAN VERKEERDEVLEI FICKSBURG High Combined Potential CLOCOLAN EXCELSIOR JACOBSDAL PETRUSBURG BLOEMFONTEIN THABA NCHU LADYBRAND LOCALITY PLAN TWEESPRUIT Economic BOTSHABELO THABA PATSHOA KOFFIEFONTEIN OPPERMANSDORP Power HOBHOUSE DEWETSDORP REDDERSBURG EDENBURG WEPENER LUCKHOFF FAURESMITH houses JAGERSFONTEIN VAN STADENSRUST TROMPSBURG SMITHFIELD DEPARTMENT LOCAL GOVERNMENT & HOUSING PHILIPPOLIS SPRINGFONTEIN Arid SPATIAL PLANNING DIRECTORATE ZASTRON SPATIAL INFORMATION SERVICES ROUXVILLE BETHULIE -

An Investigation of Skeletons from Type-R Settlements Along the Riet and Orange Rivers, South Africa, Using Stable Isotope Analysis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cape Town University OpenUCT An Investigation of Skeletons from Type-R Settlements along the Riet and Orange Rivers, South Africa, Using Stable Isotope Analysis Nandi Masemula Dissertation presented for the degree of Masters of Science in the Department of Archaeology University of Cape Town UniversityFebruary of 2015Cape Town Professor Judith Sealy The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Plagiarism Declaration I know the meaning of plagiarism and declare that all of the work in this dissertation, save for that which is properly acknowledged, is my own. 1 Abstract In the last centuries before incorporation into the Cape Colony, the Riet and Orange River areas of the Northern Cape, South Africa were inhabited by communities of hunter-gatherers and herders whose life ways are little understood. These people were primarily of Khoesan descent, but their large stone-built stock pens attest to the presence of substantial herds of livestock, very likely for trade. This region was too dry for agriculture, although we know that there were links with Tswana-speaking agricultural communities to the north, because of the presence of characteristic styles of copper artefacts in Riet River graves. -

Arid Areas Report, Volume 1: District Socio�Economic Profile 2007 NO 1 and Development Plans

Arid Areas Report, Volume 1: District socio-economic profile 2007 NO 1 and development plans Arid Areas Report, Volume 1: District socio-economic profile and development plans Centre for Development Support (IB 100) University of the Free State PO Box 339 Bloemfontein 9300 South Africa www.ufs.ac.za/cds Please reference as: Centre for Development Support (CDS). 2007. Arid Areas Report, Volume 1: District socio-economic profile and development plans. CDS Research Report, Arid Areas, 2007(1). Bloemfontein: University of the Free State (UFS). CONTENTS I. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 II. Geographic overview ........................................................................................................ 2 1. Namaqualand and Richtersveld ................................................................................................... 3 2. The Karoo................................................................................................................................... 4 3. Gordonia, the Kalahari and Bushmanland .................................................................................... 4 4. General characteristics of the arid areas ....................................................................................... 5 III. The Western Zone (Succulent Karoo) .............................................................................. 8 1. Namakwa District Municipality ..................................................................................................