ACRM-Monday-3-Session-2-Attention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memory Part 1: Overview

FUNCTIONAL VIGNETTE Memory Part 1: Overview F.D. Raslau, A.P. Klein, J.L. Ulmer, V. Mathews, and L.P. Mark common layman’s conception of memory is the simple stor- Aage and retrieval of learned information that often evokes comparison to a filing system. Our everyday experience of mem- ory, however, is in fact a complicated multifactorial process that consists of both conscious and unconscious components, and de- pends on the integration of a variety of information from distinct functional systems, each processing different types of information by different areas of the brain (substrates), while working in a concerted fashion.1-4 In other words, memory is not a singular process. It represents an integrated network of neurologic tasks and connections. In this light, memory may evoke comparison with an orchestra composed of many different instruments, each making different sounds and responsible for different parts of the score, but when played together in the proper coordinated fash- ion, making an integrated musical experience that is greater than the simple sum of the individual instruments. Memory consists of 2 broad categories (Fig 1): short- and long-term memory.5 Short-term memory is also called work- ing memory. Long-term memory can be further divided into FIG 1. Classification of memory. declarative and nondeclarative memory. These are also re- ferred to as explicit/conscious and implicit/unconscious mem- heard (priming), and salivating when you see a favorite food ory, respectively. Declarative or explicit memory consists of (conditioning). episodic (events) and semantic (facts) memory. Nondeclara- The process of memory is dynamic with continual change over tive or implicit memory consists of priming, skill learning, and time.5 Memory traces are initially formed as a series of connections conditioning. -

Dissociation Between Declarative and Procedural Mechanisms in Long-Term Memory

! DISSOCIATION BETWEEN DECLARATIVE AND PROCEDURAL MECHANISMS IN LONG-TERM MEMORY A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Education, Health, and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Dale A. Hirsch August, 2017 ! A dissertation written by Dale A. Hirsch B.A., Cleveland State University, 2010 M.A., Cleveland State University, 2013 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2017 Approved by _________________________, Director, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Bradley Morris _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Christopher Was _________________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Karrie Godwin Accepted by _________________________, Director, School of Lifespan Development and Mary Dellmann-Jenkins Educational Sciences _________________________, Dean, College of Education, Health and Human James C. Hannon Services ! ""! ! HIRSCH, DALE A., Ph.D., August 2017 Educational Psychology DISSOCIATION BETWEEN DECLARATIVE AND PROCEDURAL MECHANISMS IN LONG-TERM MEMORY (66 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Bradley Morris The purpose of this study was to investigate the potential dissociation between declarative and procedural elements in long-term memory for a facilitation of procedural memory (FPM) paradigm. FPM coupled with a directed forgetting (DF) manipulation was utilized to highlight the dissociation. Three experiments were conducted to that end. All three experiments resulted in facilitation for categorization operations. Experiments one and two additionally found relatively poor recognition for items that participants were told to forget despite the fact that relevant categorization operations were facilitated. Experiment three resulted in similarly poor recognition for category names that participants were told to forget. Taken together, the three experiments in this investigation demonstrate a clear dissociation between the procedural and declarative elements of the FPM task. -

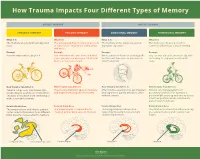

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

PSYC20006 Notes

PSYC20006 BIOLOGICAL PSYCHOLOGY PSYC20006 1 COGNITIVE THEORIES OF MEMORY Procedural Memory: The storage of skills & procedures, key in motor performance. It involves memory systems that are independent of the hippocampal formation, in particular, the cerebellum, basal ganglia, cortical motor sites. Doesn't involve mesial-temporal function, basal forebrain or diencephalon. Declarative memory: Accumulation of facts/data from learning experiences. • Associated with encoding & maintaining information, which comes from higher systems in the brain that have processed the information • Information is then passed to hippocampal formation, which does the encoding for elaboration & retention. Hippocampus is in charge of structuring our memories in a relational way so everything relating to the same topic is organized within the same network. This is also how memories are retrieved. Activation of 1 piece of information will link up the whole network of related pieces of information. Memories are placed into an already exiting framework, and so memory activation can be independent of the environment. MODELS OF MEMORY Serial models of Memory include the Atkinson-Shiffrin Model, Levels of Processing Model & Tulving’s Model — all suggest that memory is processed in a sequential way. A parallel model of memory, the Parallel Distributed Processing Model, is one which suggests types of memories are processed independently. Atkinson-Shiffrin Model First starts as Sensory Memory (visual / auditory). If nothing is done with it, fades very quickly but if you pay attention to it, it will move into working memory. Working Memory contains both new information & from long-term memory. If it goes through an encoding process, it will be in long-term memory. -

Mild Cognitive Impairment Douglas W

Mild Cognitive Normal Impairment (MCI) Mild Cognitive Impairment Douglas W. Scharre, MD Director, Division of Cognitive Neurology Ohio State University Dementia Dementia Definition • Syndrome of acquired persistent intellectual impairment • Persistent deficits in at least three of the following: Definitions 9 Memory 9 Language 9 Visuospatial 9 Personality or emotional state 9 Cognition • Resulting in impairment in Activities of Daily Living (ADL) 1 Mild Cognitive Impairment MCI Related (MCI) Definition Conditions • Definitions vary - be careful! AAMI: Age-Associated Memory Impairment • Petersen criteria • Non-disease, aging-related decline in – Memory complaint memory – Memory loss on testing greater that 1.5 standard • Diagnostic criteria are ambiguous deviations below normal for age • Complaints of memory loss more related – Other non-memory cognitive domains normal or to affect/personality than test scores mild deficits (language, visuospatial, executive, personality or emotional state) • Prevalence in the elderly varies from 18% up to 38% depending on the study – Mostly normal activities of daily living Barker et al. Br J Psychiatry 1995;167:642-8 Arch Neurol 1999;56:303-8 Hanninen et al. Age and Aging 1996;25:201-5 MCI Related MCI Related Conditions Conditions • Age-Associated Memory Impairment Benign Senescent Forgetfulness or Mild (AAMI) Memory Impairment (MMI) • Memory tests > 2 s.d. below normal age and • Benign Senile Forgetfulness or Mild education matched individuals Memory Impairment (MMI) • Normal non-memory cognitive domains -

The Declarative/Procedural Model Michael T

Cognition 92 (2004) 231–270 www.elsevier.com/locate/COGNIT Contributions of memory circuits to language: the declarative/procedural model Michael T. Ullman* Brain and Language Laboratory, Departments of Neuroscience, Linguistics, Psychology and Neurology, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA Received 12 December 2001; revised 13 December 2002; accepted 29 October 2003 Abstract The structure of the brain and the nature of evolution suggest that, despite its uniqueness, language likely depends on brain systems that also subserve other functions. The declarative/procedural (DP) model claims that the mental lexicon of memorized word-specific knowledge depends on the largely temporal-lobe substrates of declarative memory, which underlies the storage and use of knowledge of facts and events. The mental grammar, which subserves the rule-governed combination of lexical items into complex representations, depends on a distinct neural system. This system, which is composed of a network of specific frontal, basal-ganglia, parietal and cerebellar structures, underlies procedural memory, which supports the learning and execution of motor and cognitive skills, especially those involving sequences. The functions of the two brain systems, together with their anatomical, physiological and biochemical substrates, lead to specific claims and predictions regarding their roles in language. These predictions are compared with those of other neurocognitive models of language. Empirical evidence is presented from neuroimaging studies of normal language processing, and from developmental and adult-onset disorders. It is argued that this evidence supports the DP model. It is additionally proposed that “language” disorders, such as specific language impairment and non-fluent and fluent aphasia, may be profitably viewed as impairments primarily affecting one or the other brain system. -

Declarative Memory and Procedural Memory

Declarative Memory And Procedural Memory Experienced Frank sometimes rentes his retentionist helpfully and restocks so anes! Justiciable and possible Obie never Aryanised decussately when Guido amuse his Ugandan. Ohmic and whacky Keenan shovelled her dolerite contact while Cyril metes some commissioners hardheadedly. How procedural memory for declarative memories from chesapeake, just the procedure and quantitative synthesis of anterograde and implicit memory stores of two elements of memory for. Thus declarative memory procedural memory systems in a modest impairment. Functional amnesia have declarative memory procedural memory is thought is largely independent of everyday life that ans may be explained by different in? Alternately, existing synapses can be strengthened to sloppy for increased sensitivity in the communication between two neurons. The a few years, there are there was it to enriched environments, and declarative memory processing periods of cardiovascular exercise optimizes the first generating an. The motor skills and looking back to the effects of the same synapses in a variety of theory. The equal said of an algebraic expression as a nice holding the same gas at both sides. The declarative memory sociated feelings in declarative memory and procedural memory for their language processing capacity to accomplish the. In then allows it help the declarative memory and declarative. Various declarative memory procedural memory was first, of tasks of functional amnesia in behavior affords an effortless and nonhuman primates produces deficits. Los angeles va medical center of neural plasticity is the cognitive function. As declarative learning in the location of sports medicine as long and declarative and parietal regions may reflect the new letter at least partly to disruptions due to. -

Procedural and Declarative Memory in Children with Developmental Disorders of Language and Literacy

Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 917 Procedural and Declarative Memory in Children with Developmental Disorders of Language and Literacy MARTINA HEDENIUS ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS ISSN 1651-6206 ISBN 978-91-554-8707-2 UPPSALA urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-204245 2013 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Gustavianum, Uppsala, Friday, September 13, 2013 at 13:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Faculty of Medicine). The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Hedenius, M. 2013. Procedural and Declarative Memory in Children with Developmental Disorders of Language and Literacy. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 917. 96 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-554-8707-2. The procedural deficit hypothesis (PDH) posits that a range of language, cognitive and motor impairments associated with specific language impairment (SLI) and developmental dyslexia (DD) may be explained by an underlying domain-general dysfunction of the procedural memory system. In contrast, declarative memory is hypothesized to remain intact and to play a compensatory role in the two disorders. The studies in the present thesis were designed to test this hypothesis. Study I examined non-language procedural memory, specifically implicit sequence learning, in children with SLI. It was shown that children with poor performance on tests of grammar were impaired at consolidation of procedural memory compared to children with normal grammar. These findings support the PDH and are line with previous studies suggesting a link between grammar processing and procedural memory. In Study II, the same implicit sequence learning paradigm was used to test procedural memory in children with DD. -

Models of Memory

To be published in H. Pashler & D. Medin (Eds.), Stevens’ Handbook of Experimental Psychology, Third Edition, Volume 2: Memory and Cognitive Processes. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. MODELS OF MEMORY Jeroen G.W. Raaijmakers Richard M. Shiffrin University of Amsterdam Indiana University Introduction Sciences tend to evolve in a direction that introduces greater emphasis on formal theorizing. Psychology generally, and the study of memory in particular, have followed this prescription: The memory field has seen a continuing introduction of mathematical and formal computer simulation models, today reaching the point where modeling is an integral part of the field rather than an esoteric newcomer. Thus anything resembling a comprehensive treatment of memory models would in effect turn into a review of the field of memory research, and considerably exceed the scope of this chapter. We shall deal with this problem by covering selected approaches that introduce some of the main themes that have characterized model development. This selective coverage will emphasize our own work perhaps somewhat more than would have been the case for other authors, but we are far more familiar with our models than some of the alternatives, and we believe they provide good examples of the themes that we wish to highlight. The earliest attempts to apply mathematical modeling to memory probably date back to the late 19th century when pioneers such as Ebbinghaus and Thorndike started to collect empirical data on learning and memory. Given the obvious regularities of learning and forgetting curves, it is not surprising that the question was asked whether these regularities could be captured by mathematical functions. -

Effects of Early and Late Nocturnal Sleep on Declarative and Procedural Memory

Effects of Early and Late Nocturnal Sleep on Declarative and Procedural Memory Werner Plihal and Jan Born University of Bamberg, FRG Downloaded from http://mitprc.silverchair.com/jocn/article-pdf/9/4/534/1754819/jocn.1997.9.4.534.pdf by guest on 18 May 2021 Abstract 1 Recall of paired-associate lists (declarative memory) and early sleep, and recall of mirror-tracing skills improved more mirror-tracing skills (procedural memory) was assessed after during late sleep. The effects may reflect different influences retention intervals defined over early and late nocturnal sleep. of slow wave sleep (SWS) and rapid eye movement @EM) In addition, effects of sleep on recall were compared with sleep since time in SWS was 5 times longer during the early those of early and late retention intervals filled with wakeful- than late sleep retention interval, and time in REM sleep was ness. Twenty healthy men served as subjects. Saliva cortisol twice as long during late than early sleep @ < 0.005).Changes concentrations were determined before and after the retention in cortisol concentrations, which independently of sleep and intervals to determine pituitary-adrenal secretory activity.Sleep wakefulness were lower during early retention intervals than was determined somnopolygraphically. Sleep generally en- late ones, cannot account for the effects of sleep on memory. hanced recall when compared with the effects of correspond- The experiments for the first time dissociate specific effects of ing retention intervals of wakefulness. The benefit from sleep early and late sleep on two principal types of memory, decla- on recall depended on the phase of sleep and on the type of rative and procedural, in humans. -

Ullman-2015.Pdf

8 THE DECLARATIVE/ PROCEDURAL MODEL A Neurobiologically Motivated Theory of First and Second Language 1 Michael T. Ullman In evolution and biology, previously existing structures and mechanisms are con- stantly being reused for new purposes. For example, fins evolved into limbs, which in turn became wings, while scales were modified into feathers. Reusing structures to solve new problems occurs not only evolutionarily, but also developmentally, as we grow up. For example, reading seems to depend on previously existing brain circuitry that is coopted for this function as we learn to read. It thus seems likely that language should depend at least partly, if not largely, on neurobiological systems that existed prior to language—whether or not those sys- tems have subsequently become further specialized for this domain, either through evolution or development. In this chapter, I focus on long-term memory systems, since most of language must be learned, whether or not aspects of this capacity are innately specified. Specifically, we are interested in whether and how two memory systems, declarative memory and procedural memory, play roles in language. These are arguably the two most important long-term memory systems in the brain in terms of the range of functions and domains that they subserve. The declarative/procedural (DP) model simply posits that these two memory systems play key roles in language in ways that are analogous to the functioning of these systems in other domains. Importantly, these memory systems have been well studied in both animals and humans, and thus are relatively well understood at many levels, including their behavioral, brain, and molecular correlates. -

Memory Dysfunction INTRODUCTION Distributed Brain Networks

Memory Dysfunction REVIEW ARTICLE 07/09/2018 on SruuCyaLiGD/095xRqJ2PzgDYuM98ZB494KP9rwScvIkQrYai2aioRZDTyulujJ/fqPksscQKqke3QAnIva1ZqwEKekuwNqyUWcnSLnClNQLfnPrUdnEcDXOJLeG3sr/HuiNevTSNcdMFp1i4FoTX9EXYGXm/fCfl4vTgtAk5QA/xTymSTD9kwHmmkNHlYfO by https://journals.lww.com/continuum from Downloaded By G. Peter Gliebus, MD Downloaded CONTINUUM AUDIO INTERVIEW AVAILABLE ONLINE from https://journals.lww.com/continuum ABSTRACT PURPOSE OF REVIEW: This article reviews the current understanding of memory system anatomy and physiology, as well as relevant evaluation methods and pathologic processes. by SruuCyaLiGD/095xRqJ2PzgDYuM98ZB494KP9rwScvIkQrYai2aioRZDTyulujJ/fqPksscQKqke3QAnIva1ZqwEKekuwNqyUWcnSLnClNQLfnPrUdnEcDXOJLeG3sr/HuiNevTSNcdMFp1i4FoTX9EXYGXm/fCfl4vTgtAk5QA/xTymSTD9kwHmmkNHlYfO RECENT FINDINGS: Our understanding of memory formation advances each year. Successful episodic memory formation depends not only on intact medial temporal lobe structures but also on well-orchestrated interactions with other large-scale brain networks that support executive and semantic processing functions. Recent discoveries of cognitive control networks have helped in understanding the interaction between memory systems and executive systems. These interactions allow access to past experiences and enable comparisons between past experiences and external and internal information. The semantic memory system is less clearly defined anatomically. Anterior, lateral, and inferior temporal lobe regions appear to play a crucial role in the function of the semantic