Handshape Is the Hardest Path in Portuguese Sign Language Acquisition Towards a Universal Modality Constraint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning/Teaching Philosophy in Sign Language As a Cultural Issue

DOI: 10.15503/jecs20131-9-19 Journal of Education Culture and Society No. 1_2013 9 Learning/teaching philosophy in sign language as a cultural issue Maria de Fátima Sá Correia [email protected] Orquídea Coelho [email protected] António Magalhães [email protected] Andrea Benvenuto [email protected] Abstract This paper is about the process of learning/teaching philosophy in a class of deaf stu- dents. It starts with a presentation of Portuguese Sign Language that, as with other sign lan- guages, is recognized as a language on equal terms with vocal languages. However, in spite of the recognition of that identity, sign languages have specifi city related to the quadrimodal way of their production, and iconicity is an exclusive quality. Next, it will be argued that according to linguistic relativism - even in its weak version - language is a mould of thought. The idea of Philosophy is then discussed as an area of knowledge in which the author and the language of its production are always present. Finally, it is argued that learning/teaching Philosophy in Sign Language in a class of deaf students is linked to deaf culture and it is not merely a way of overcoming diffi culties with the spoken language. Key words: Bilingual education, Deaf culture, Learning-teaching Philosophy, Portuguese Sign Language. According to Portuguese law (Decreto-Lei 3/2008 de 7 de Janeiro de 2008 e Law 21 de 12 de Maio de 2008), in the “escolas de referência para a educação bilingue de alunos surdos” (EREBAS) (reference schools for bilingual education of deaf stu- dents) deaf students have to attend classes in Portuguese Sign Language. -

The Role of Technology to Teaching and Learning Sign Languages: a Systematic Mapping

The Role of Technology to Teaching and Learning Sign Languages: A Systematic Mapping Venilton FalvoJr Lilian Passos Scatalon Ellen Francine Barbosa University of Sao˜ Paulo (ICMC-USP) University of Sao˜ Paulo (ICMC-USP) University of Sao˜ Paulo (ICMC-USP) Sao˜ Carlos-SP, Brazil Sao˜ Carlos-SP, Brazil Sao˜ Carlos-SP, Brazil [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—Context: The teaching and learning process has Thus, for the development of effective educational environ- become essential for the evolution of the society as a whole. ments, it is essential that intrinsic user characteristics are con- However, there are still major challenges for achieving the global sidered, such as their physical limitations. In this sense, deaf goals of education, especially if we consider the portion of the population with some type of physical disability. In this and hard of hearing (D/HH) people face struggles in education context, according to World Federation of the Deaf (WFD), deaf due to inappropriate learning environments, especially when children face many difficulties in education due to inappropriate there is a lack of support for sign languages [3]. learning environments. Also, this problem is compounded by the Sign languages are fully fledged natural languages, struc- lack of consistency worldwide in the provision of sign language turally distinct from the spoken languages. There is also an interpreting and translation. Motivation: However, the advent of technology is having a significant impact on the way that international sign language, which is used by deaf people sign language interpreters and translators work. In this sense, in international meetings and informally when travelling and the union between Information and Communication Technologies socializing. -

![Portuguese Sign Language [Psr] (A Language of Portugal)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2421/portuguese-sign-language-psr-a-language-of-portugal-1212421.webp)

Portuguese Sign Language [Psr] (A Language of Portugal)

“Portuguese Sign Language [psr] (A language of Portugal) • Alternate Names: LGP, Lingua Gestual Portuguesa • Population: 52,000 (2014 IMB). 60,000 sign language users (2014 EUD). 150,000 deaf (2010 Federação Portuguesa das Associações de Surdos). • Location: Scattered, including Azores and Madeira islands. • Language Status: 5 (Developing). • Dialects: Lisbon, Oporto. Historical influence from Swedish Sign Language [swl]. Older signers attended separate schools for boys and girls in Lisbon and Oporto, resulting in some variation by gender and region. (Van Cleve 1986) These differences have largely disappeared in younger signers. No apparent relationship to Spanish sign language, based on a lexical comparison of non-iconic signs. (Eberle and Eberle 2012). • Typology: One-handed fingerspelling. • Language Use: While Portuguese Sign Language is the primary language of communication for most deaf people, widely varying degrees of bilingualism (spoken and written) in Portuguese [por] are common. Written Portuguese is valued for access to mainstream society and employment. • Language Development: Videos. Dictionary. Grammar. • Other Comments: Fingerspelling system shows many differences from other European countries. 100 working sign language interpreters (2014 EUD). Taught as L2 at the university level. Christian (Roman Catholic).” Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.) 2015. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Eighteenth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com. Related Readings Carmo, Patrícia do, Alexandre Castro-Caldas, Ronice Müller de Quadros, Joana Castelo Branco, and Ana Mineiro 2013 Handshape is the Hardest Path in Portuguese Sign Language Acquisition: Towards a Universal Modality Constraint. Sign Language & Linguistics 16(1): 75. Santos, Cátia, and António Luís Carvalho 2012 The Core Competencies of the Portuguese Supervisor's Sign Language Interpreters’ Students. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

Verb Agreement in Brazilian Sign Language: Morphophonology, Syntax & Semantics

Guilherme Lourenço Verb agreement in Brazilian Sign Language: Morphophonology, Syntax & Semantics Belo Horizonte Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais 2018 Guilherme Lourenço Verb agreement in Brazilian Sign Language: Morphophonology, Syntax & Semantics Doctoral dissertation submitted to the Post- Graduate Program in Linguistic Studies (Poslin) at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, as a requisite to obtain the title of Doctor in Linguistics. Area: Theoretical and Descriptive Linguistics Research line: Studies on Formal Syntax Adviser: Dr. Fábio Bonfim Duarte Co-adviser: Dr. Ronnie B. Wilbur Belo Horizonte Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais 2018 Ficha catalográfica elaborada pelos Bibliotecários da Biblioteca FALE/UFMG Lourenço, Guilherme. L892v Verb agreement in Brazilian Sign Language [manuscrito] : Morphophonology, Syntax & Semantics / Guilherme Lourenço. – 2018. 320 f., enc. Orientador: Fábio Bonfim Duarte. Coorientador: Ronnie B. Wilbur Área de concentração: Linguística Teórica e Descritiva. Linha de Pesquisa: Estudos em Sintaxe Formal. Tese (doutorado) – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Faculdade de Letras. Bibliografia: f. 266-286. Apêndices: f. 287-320. 1. Língua brasileira de sinais – Sintaxe – Teses. 2. Língua brasileira de sinais – Concordância – Teses. 3. Língua brasileira de sinais – Gramática – Teses. 4. Língua brasileira de sinais – Verbos – Teses. I. Duarte, Fábio Bonfim. II. Wilbur, Ronnie B. III. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Faculdade de Letras. IV. Título. CDD: 419 VERB AGREEMENT IN BRAZILIAN SIGN -

Marcin Mizak Sign Language – a Real and Natural Language

LUBELSKIE MATERIAŁY NEOFILOLOGICZNE NR 35, 2011 Marcin Mizak Sign Language – A Real and Natural Language 1. Introduction It seems reasonable to begin a discussion on the “realness” and “naturalness” of sign language by comparing it to other human languages of whose “real” and “natural” status there can be no doubt whatsoever. They will be our reference point in the process of establishing the status of sign language. The assumption being made in this paper is that all real and natural languages share certain characteristics with one another, that they all behave in a certain way and that certain things happen to all of them. If it transpires that the same characteristics and behaviours are also shared by sign language and that whatever happens to real and natural languages also happens to sign language then the inevitable conclusion follows: sign language is indeed a real and natural language 1. 2. The number of languages in the world One of the first things to be noticed about real and natural languages is their great number. Ethnologue: Languages of the World , one of the most reliable and comprehensive encyclopedic reference publications, catalogues in its 16 th edition of 2009 6,909 known living languages in 1 The designation “sign language,” as used in this article, refers to the languages used within communities of the deaf. American Sign Language, for example, is a sign language in this sense. Artificially devised systems, such as Signed English, or Manual English, are not sign languages in this sense. Sign Language – A Real and Natural Language 51 the world today 2. -

DEAF INTERPRETING in EUROPE Exploring Best Practice in the Field

DEAF INTERPRETING IN EUROPE Exploring best practice in the field Christopher Stone, Editor 1 Deaf Interpreting in Europe. Exploring best practice in the field. Editor: Christopher Stone. Danish Deaf Association. 2018. ISBN 978-87-970271-0-3 Co-funded by the Erasmus+ programme of the European Union FSupportedunded by bythe the Co-funded by the Erasmus+ programmeprogramme Erasmus+ programme of the European Union of the European UnionUnion 2 How to access the emblem You can download the emblem from our website in two different formats. After downloading the .zip file, please click 'extract all files' or unzip the folder to access the .eps file required. The different formats are: . JPG: standard image format (no transparency). Ideal for web use because of the small file size. EPS: requires illustration software such as Adobe Illustrator. Recommended for professional use on promotional items and design. Some visual do’s and don’ts ✓. Do resize the emblem if needed. The minimum size it can be is 10mm in height. Co-funded by the Erasmus+ programme of the European Union Co-funded by the Erasmus+ programme of the European Union Preface This publication is the outcome of the Erasmus+ project Developing Deaf Interpreting. The project has been underway since September 2015 and has been a cooperation between Higher Educational Institutions in Europe undertaking deaf interpreter training, as well as national and European NGOs in the field. The project partners are: Institute for German Sign Language (IDGS) at Hamburg University, Coimbra Polytechnic Institute (IPC), Humak University of Applied Sciences, European Forum of Sign Language Interpreters (efsli), and the Danish Deaf Association (DDA). -

Sign Languages

200-210 Sign languages 200 Arık, Engin: Describing motion events in sign languages. – PSiCL 46/4, 2010, 367-390. 201 Buceva, Pavlina; Čakărova, Krasimira: Za njakoi specifiki na žestomimičnija ezik, izpolzvan ot sluchouvredeni lica. – ESOL 7/1, 2009, 73-79 | On some specific features of the sign language used by children with hearing disorders. 202 Dammeyer, Jesper: Tegnsprogsforskning : om tegnsprogets bidrag til viden om sprog. – SSS 3/2, 2012, 31-46 | Sign language research : on the contribution of sign language to the knowledge of languages | E. ab | Electronic publ. 203 Deaf around the world : the impact of language / Ed. by Gaurav Mathur and Donna Jo Napoli. – Oxford : Oxford UP, 2011. – xviii, 398 p. 204 Fischer, Susan D.: Sign languages East and West. – (34), 3-15. 205 Formational units in sign languages / Ed. by Rachel Channon ; Harry van der Hulst. – Berlin : De Gruyter Mouton ; Nijmegen : Ishara Press, 2011. – vi, 346 p. – (Sign language typology ; 3) | Not analyzed. 206 Franklin, Amy; Giannakidou, Anastasia; Goldin-Meadow, Susan: Negation, questions, and structure building in a homesign system. – Cognition 118/3, 2011, 398-416. 207 Gebarentaalwetenschap : een inleiding / Onder red. van Anne E. Baker ; Beppie van den Bogaerde ; Roland Pfau ; Trude Schermer. – Deventer : Van Tricht, 2008. – 328 p. 208 Kendon, Adam: A history of the study of Australian Aboriginal sign languages. – (50), 383-402. 209 Kendon, Adam: Sign languages of Aboriginal Australia : cultural, semi- otic and communicative perspectives. – Cambridge : Cambridge UP, 2013. – 562 p. | First publ. 1988; cf. 629. 210 Kudła, Marcin: How to sign the other : on attributive ethnonyms in sign languages. – PFFJ 2014, 81-92 | Pol. -

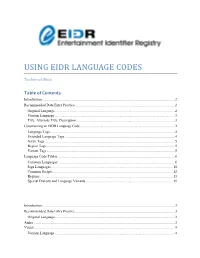

Using Eidr Language Codes

USING EIDR LANGUAGE CODES Technical Note Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Recommended Data Entry Practice .............................................................................................................. 2 Original Language..................................................................................................................................... 2 Version Language ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Title, Alternate Title, Description ............................................................................................................. 3 Constructing an EIDR Language Code ......................................................................................................... 3 Language Tags .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Extended Language Tags .......................................................................................................................... 4 Script Tags ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Region Tags ............................................................................................................................................. -

Covid-19 Disability Inclusive Response

PRACTICAL TOOLS for a disability inclusive COVID-19 response Source: The Leprosy Mission Note: Comprehensive guidelines, recommendations and overviews of resources on how to ensure that people with disabilities are included in COVID-19 responses can be found via WHO, IDA and IDDC / Core Group (see links page 3). In this document we aim to highlight the practical tools, such as sign language videos, easy-read materials, accessible protection methods, etc. This document will be continuously updated in the coming weeks and months (see also www.dcdd.nl/resources). DCDD gathers tools that have been developed by our network participants and other disability organisations. DCDD is not responsible for the content of these tools. Do you have tools you would like us to include? Please send an email to [email protected] Content KEY RECOMMENDATIONS & REPOSITORIES ............................................... 3 EASY-READ ................................................................................................. 4 SIGN LANGUAGE ........................................................................................ 5 INFOGRAPHICS & VISUALS ......................................................................... 7 ACCESS TO HEALTH ................................................................................... 7 PROTECTION METHODS ............................................................................. 8 COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT ........................................................................ 8 Practical Tools for a disability inclusive -

The Sociolinguistics of Sing Languages Edited by Ceil Lucas Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521791375 - The Sociolinguistics of Sing Languages Edited by Ceil Lucas Index More information Index Aarons, D. 14–15 and Pidgin Sign English 56 acquisition 51, 202–3 politeness in 122 Adegbija, E. 204 recognition of 151, 168–9, 215 n2 adjacency pairs 123 regional variation 61 advertisements 204, 212, 214f repair strategies 130 Africa 30, 215 n2 research on variation 77–86, 89, 97–109 African American signing 87 sermons 142 African American Vernacular English (AAVE) social attitude 17 65, 70–3, 207–8, 215 n6 status 102, 104, 169, 206, 209 age 61, 95, 96 syntactic variation 64 agent–beneficiary directionality 82, 89 teaching and learning 202 Akach, P. 14–15 see also African American signing; Tactile Allport, G.W. 183 ASL Allsop, L. 24, 192, 195, 211, 212 Anderson, L. 25–7, 26f,27f Almond, B. 165 Ann, J. 54 Altbach, P. 147 Anthony, D. 153 American Sign Language (ASL) Aramburo, A. 87 age differences 61 ASL see American Sign Language code switching 64, 192–3 Auslan see Australian Sign Language cohesion 135–6 Austin, J. 117 constructed dialogue and action 133–5 Australian Sign Language (Auslan) 16, 23, 28, creolization 57 152, 215 n2 DEAF 61–2, 85, 101–4, 103f, 106, 107, 124 see also Warlpiri sign language Deaf attitudes towards 197 definition of 16–17, 23 back-channeling 86, 142 diachronic variation 83–4 Baer, A.M. 128 dictionaries 6, 78, 79–80, 152 Bahan, B. 140–1, 168, 212 discourse 86 Bailey, G. et al. 74, 75 discourse markers 132–3 Baker, C. -

Delegate Handbook

Theoretical Issues in Sign Language Research Conference 10 – 13 July 2013 University College London DELEGATE HANDBOOK TISLR is the research conference of the Sign Language Linguistics Society CONTENTS 2 Welcome 3 TISLR committees 4 General Information for delegates 5-7 Programme 7-9 Poster Session 1 9-10 Poster Session 2 11-12 Poster Session 3 13 UCL venue map and WiFi connection 14 Local area and places to eat 16-18 Delegate list TISLR 11 is hosted by University College London DCAL Centre (ESRC Deafness Cognition and Language Research Centre) 49 Gordon Square London WC1H 0PD, England Tel: +44(0)20 7679 8679 Fax: +44(0)20 7679 8691 Minicom: +44(0)20 7679 8693 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.ucl.ac.uk/dcal We are very grateful to the National Science Foundation (Award No. BCS-1251849) and the National Technical Institute for the Deaf for their help with interpreting services and to our sponsors and contributors: Access to Work Mocaplab The Economic and Social Research Council Mouton de Gruyter The Embassy of Japan National Science Foundation Fireco Rochester Institute of Technology Gallaudet University Press Sieratzki Charitable Trust John Benjamins Publishers University College London Equality & Diversity Team Professor Bencie Woll FBA, Director University College London 49 Gordon Square 10 July 2013 London WC1H 0PD Tel: +44 (0)20 7679 8670 Fax: +44 (0)20 7679 8691 Minicom/Textphone: +44 (0)20 7679 8693 Web: www.dcal.ucl.ac.uk E-mail: [email protected] THE 11TH CONFERENCE ON THEORETICAL ISSUES IN SIGN LANGUAGE RESEARCH On behalf of DCAL, UCL, and London, welcome to TISLR XI! The first international conference on sign language research was held in Stockholm in 1979.