From Its Headwaters Until It Reaches Fossil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Havasupai Nation Field Trip May 16 – 20, 2012 by Melissa Armstrong

Havasupai Nation Field Trip May 16 – 20, 2012 By Melissa Armstrong The ESA SEEDS program had a field trip to Flagstaff, AZ the Havasupai Nation in Western Grand Canyon from May 16 – 20, 2012 as part of the Western Sustainable Communities project with funding from the David and Lucille Packard Foundation. The focus of the field trip was on water sustainability of the Colorado River Basin from a cultural and ecological perspective. The idea for this field trip arose during the Western Regional Leadership Meeting held in Flagstaff in April 2011 as a way to ground our meeting discussions in one of the most iconic places of the Colorado Plateau – the Grand Canyon. SEEDS alumnus Hertha Woody helped ESA connect with the Havasupai Nation; she worked closely with the former Havasupai tribal council during her tenure with Grand Canyon Trust as a tribal liaison. Hertha was instrumental in the planning of this experience for students. In attendance for this field trip were 17 undergraduate and graduate students, 1 alumnus, 1 Chapter advisor, and 2 ESA staff members (21 people total), representing eight Chapter campuses (Dine College Tuba City and Shiprock campuses, ASU, NAU, UNM, SIPI, NMSU, Stanford) – See Appendix A. The students were from a diverse and vibrant background; 42% were Native American, 26% White, 26% Hispanic and 5% Asian. All four of our speakers were Native American. The overall experience was profound given the esteem and generosity of the people who shared their knowledge with our group, the scale of the issues that were raised, the incredibly beautiful setting of Havasu Canyon, and the significant effort that it took to hike to Supai Village and the campgrounds – approximately 30 miles in three days at an elevation change of 1,500 feet each way. -

Havasu Canyon Watershed Rapid Watershed Assessment Report June, 2010

Havasu Canyon Watershed Rapid Watershed Assessment Report June, 2010 Prepared by: USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service University of Arizona, Water Resources Research Center In cooperation with: Coconino Natural Resource Conservation District Arizona Department of Agriculture Arizona Department of Environmental Quality Arizona Department of Water Resources Arizona Game & Fish Department Arizona State Land Department USDA Forest Service USDA Bureau of Land Management Released by: Sharon Megdal David L. McKay Director State Conservationist University of Arizona United States Department of Agriculture Water Resources Research Center Natural Resources Conservation Service Principle Investigators: Dino DeSimone – NRCS, Phoenix Keith Larson – NRCS, Phoenix Kristine Uhlman – Water Resources Research Center Terry Sprouse – Water Resources Research Center Phil Guertin – School of Natural Resources The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disa bility, po litica l be lie fs, sexua l or ien ta tion, an d mar ita l or fam ily s ta tus. (No t a ll prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C., 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice or TDD). USDA is an equal employment opportunity provider and employer. Havasu Canyon Watershed serve as a platform for conservation 15010004 program delivery, provide useful 8-Digit Hydrologic Unit information for development of NRCS Rapid Watershed Assessment and Conservation District business plans, and lay a foundation for future cooperative watershed planning. -

Quantifying the Base Flow of the Colorado River: Its Importance in Sustaining Perennial Flow in Northern Arizona And

1 * This paper is under review for publication in Hydrogeology Journal as well as a chapter in my soon to be published 2 master’s thesis. 3 4 Quantifying the base flow of the Colorado River: its importance in sustaining perennial flow in northern Arizona and 5 southern Utah 6 7 Riley K. Swanson1* 8 Abraham E. Springer1 9 David K. Kreamer2 10 Benjamin W. Tobin3 11 Denielle M. Perry1 12 13 1. School of Earth and Sustainability, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86011, US 14 email: [email protected] 15 2. Department of Geoscience, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV 89154, US 16 3. Kentucky Geological Survey, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506, US 17 *corresponding author 18 19 Abstract 20 Water in the Colorado River is known to be a highly over-allocated resource, yet decision makers fail to consider, in 21 their management efforts, one of the most important contributions to the existing water in the river, groundwater. This 22 failure may result from the contrasting results of base flow studies conducted on the amount of streamflow into the 23 Colorado River sourced from groundwater. Some studies rule out the significance of groundwater contribution, while 24 other studies show groundwater contributing the majority flow to the river. This study uses new and extant 1 25 instrumented data (not indirect methods) to quantify the base flow contribution to surface flow and highlight the 26 overlooked, substantial portion of groundwater. Ten remote sub-basins of the Colorado Plateau in southern Utah and 27 northern Arizona were examined in detail. -

Clear-Water Tributaries of the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, Arizona: Stream Ecology and the Potential Impacts of Managed Flow by René E

Clear-water tributaries of the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, Arizona: stream ecology and the potential impacts of managed flow by René E. Henery ABSTRACT Heightened attention to the sediment budget for the Colorado River systerm in Grand Canyon Arizona, and the importance of the turbid tributaries for delivering sediment has resulted in the clear-water tributaries being overlooked by scientists and managers alike. Existing research suggests that clear-water tributaries are remnant ecosystems, offering unique biotic communities and natural flow patterns. These highly productive environments provide important spawning, rearing and foraging habitat for native fishes. Additionally, clear water tributaries provide both fish and birds with refuge from high flows and turbid conditions in the Colorado River. Current flow management in the Grand Canyon including beach building managed floods and daily flow oscillations targeting the trout population and invasive vegetation has created intense disturbance in the Colorado mainstem. This unprecedented level of disturbance in the mainstem has the potential to disrupt tributary ecology and increase pressures on native fishes. Among the most likely and potentially devastating of these pressures is the colonization of tributaries by predatory non-native species. Through focused conservation and management tributaries could play an important role in the protection of the Grand Canyon’s native fishes. INTRODUCTION More than 490 ephemeral and 40 perennial tributaries join the Colorado River in the 425 km stretch between Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Mead. Of the perennial tributaries in the Grand Canyon, only a small number including the Paria River, the Little Colorado River and Kanab Creek drain large watersheds and deliver large quantities of sediment to the Colorado River mainstem (Oberlin et al. -

Havasu Creek by Dan Wilson, Brent Campos, Rene Henery, Sabra Purdy and Dave Epstein

Havasu Creek By Dan Wilson, Brent Campos, Rene Henery, Sabra Purdy and Dave Epstein Havasu Creek was the most majestic tributary we saw on our trip down the Grand Canyon in March of 2005. Where the turquoise water of Havasu Creek met the turbid water of the Colorado River, a distinct color break was formed as the waters struggled to mix (figure two). The creek was lined by the towering sandy colored Muav Limestone which painted the creek with dark shadows. It was in these dark shadows that we observed approximately 70 spawning flannelmouth suckers (figure 1). All of the Grand Canyon’s native fish depend on tributaries for successful spawning. Clear water tributaries, like Havasu, provide crucial spawning habitat for native fishes (Henery 2005, this volume). Flannelmouth suckers, and the largely extirpated razorback sucker have both been observed spawning in Havasu Creek, and aggregations of flannelmouth suckers have been linked with flows in Havasu Creek though not with those in the Colorado River (Douglas and Douglas 2000). While snorkeling through Havasu Creek, we observed two very large carp upstream from the spawning suckers. The presence of common carp near spawning native fishes is very disturbing. Carp are known to be a successful omnivore worldwide. Originating from Asia, carp were introduced into the Lower Colorado River system in the late 1890s. Since then, carp, along with other alien fishes, have contributed to the demise of native fishes. Much like what we observed in Havasu Creek, Hayden (1992) describes several documented events in which carp have been found near spawning native fishes. -

FISH of the COLORADO RIVER Colorado River and Tributaries Between Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Mead

FISH OF THE COLORADO RIVER Colorado River and tributaries between Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Mead ON-LINE TRAINING: DRAFT Outline: • Colorado River • Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program (GCDAMP) • Native Fishes • Common Non-Native Fishes • Rare Non-Native Fishes • Standardized Sampling Protocol Colorado River: • The Colorado River through Grand Canyon historically hosted one of the most distinct fish assemblages in North America (lowest diversity, highest endemism) • Aquatic habitat was variable ▫ Large spring floods ▫ Cold winter temperatures ▫ Warm summer temperatures ▫ Heavy silt load • Today ▫ Stable flow releases ▫ Cooler temperatures ▫ Predation Overview: • The Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program was established in 1997 to address downstream ecosystem impacts from operation of Glen Canyon Dam and to provide research and monitoring of downstream resources. Area of Interest: from Glen Canyon Dam to Lake Mead Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program (Fish) Goals: • Maintain or attain viable populations of existing native fish, eliminate risk of extinction from humpback chub and razorback sucker, and prevent adverse modification to their critical habitat. • Maintain a naturally reproducing population of rainbow trout above the Paria River, to the extent practicable and consistent with the maintenance of viable populations of native fish. Course Purpose: • The purpose of this training course “Fish of the Colorado River” is to provide a general overview of fish located within the Colorado River below Glen Canyon Dam downstream to Lake Mead and linked directly to the GCDAMP. • Also included are brief explanations of management concerns related to the native fish species, as well as species locations. Native Fishes: Colorado River and tributaries between Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Mead Bluehead Sucker • Scientific name: Catostomus discobolus • Status: Species of Special Concern (conservation status may be at risk) • Description: Streamlined with small scales. -

Best of Arizona 2012 Williams •Bear Wallow Caf Plus: Escape • Explore •Experience •Explore Escape

CRUISING AZ BEST OF ARIZONA 2012 in a 1929 Ford AUGUST 2012 ESCAPE • EXPLORE • EXPERIENCE Things — CARL PERKINS to Do Before 31 You Die “If it weren’t for weren’t the rocks it “If in its bed, no song.” the stream have would PLUS: HOPI CHIPMUNKS • THE GRAND CANYON • JIM HARRISON • INDIAN ROAD 8 WILLIAMS • BEAR WALLOW CAFÉ • DUTCH TILTS • ASPENS • STRAWBERRY SCHOOL CONTENTS 08.12 Grand Canyon National Park Third Mesa 2 EDITOR’S LETTER > 3 CONTRIBUTORS > 4 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR > 56 WHERE IS THIS? Supai Parks Williams Oak Creek 5 THE JOURNAL 46 THE MAN IN THE CREEK Strawberry Alpine People, places and things from around the state, including Jim Harrison likes water. Actually, he loves water. Ironically, Cave Creek Hank Delaney, the most unique mail carrier in the world; he doesn’t find a lot of it in Patagonia. What he does find is Point of Pines the Bear Wallow Café, a perfect place for pie in the White inspiration for his novels. He also finds camaraderie in some PHOENIX Mountains; and Williams, our hometown of the month. of the characters who live in his neck of the woods. BY KELLY KRAMER Patagonia 18 31 THINGS TO DO BEFORE PHOTOGRAPHS BY SCOTT BAXTER YOU KICK THE BUCKET 52 SCENIC DRIVE • POINTS OF INTEREST IN THIS ISSUE Everyone needs to see the Grand Canyon before he dies, Point of Pines Road: Elk, pronghorns, bighorns, black bears, but it’s not enough to just see it. It needs to be experi- meadows, mountains, trees, eagles, herons, ospreys .. -

Grand Canyon

U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Investigations Series I–2688 14 Version 1.0 4 U.S. Geological Survey 167.5 1 BIG SPRINGS CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS LIST OF MAP UNITS 4 Pt Ph Pamphlet accompanies map .5 Ph SURFICIAL DEPOSITS Pk SURFICIAL DEPOSITS SUPAI MONOCLINE Pk Qr Holocene Qr Colorado River gravel deposits (Holocene) Qsb FAULT CRAZY JUG Pt Qtg Qa Qt Ql Pk Pt Ph MONOCLINE MONOCLINE 18 QUATERNARY Geologic Map of the Pleistocene Qtg Terrace gravel deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pc Pk Pe 103.5 14 Qa Alluvial deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pt Pc VOLCANIC ROCKS 45.5 SINYALA Qti Qi TAPEATS FAULT 7 Qhp Qsp Qt Travertine deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Grand Canyon ၧ DE MOTTE FAULT Pc Qtp M u Pt Pleistocene QUATERNARY Pc Qp Pe Qtb Qhb Qsb Ql Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Qsb 1 Qhp Ph 7 BIG SPRINGS FAULT ′ × ′ 2 VOLCANIC DEPOSITS Dtb Pk PALEOZOIC SEDIMENTARY ROCKS 30 60 Quadrangle, Mr Pc 61 Quaternary basalts (Pleistocene) Unconformity Qsp 49 Pk 6 MUAV FAULT Qhb Pt Lower Tuckup Canyon Basalt (Pleistocene) ၣm TRIASSIC 12 Triassic Qsb Ph Pk Mr Qti Intrusive dikes Coconino and Mohave Counties, Pe 4.5 7 Unconformity 2 3 Pc Qtp Pyroclastic deposits Mr 0.5 1.5 Mၧu EAST KAIBAB MONOCLINE Pk 24.5 Ph 1 222 Qtb Basalt flow Northwestern Arizona FISHTAIL FAULT 1.5 Pt Unconformity Dtb Pc Basalt of Hancock Knolls (Pleistocene) Pe Pe Mၧu Mr Pc Pk Pk Pk NOBLE Pt Qhp Qhb 1 Mၧu Pyroclastic deposits Qhp 5 Pe Pt FAULT Pc Ms 12 Pc 12 10.5 Lower Qhb Basalt flows 1 9 1 0.5 PERMIAN By George H. -

Salinity of Surface Water in the Lower Colorado River Salton Sea Area

Salinity of Surface Water in The Lower Colorado River Salton Sea Area, By BURDGE IRELAN, WATER RESOURCES OF LOWER COLORADO RIVER-SALTON SEA AREA pl. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, PROFESSIONAL PAPER 486-E . i V ) 116) P, UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1971 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract El Ionic budget of the Colorado River from Lees Ferry to Introduction 2 Imperial Dam, 1961-65-Continued General chemical characteristics of Colorado River Tapeats Creek E26 water from Lees Ferry to Imperial Dam 2 Havasu Creek -26 Lees Ferry . 4 Virgin River - 26 Grand Canyon 6 Unmeasured inflow between Grand Canyon and Hoover Dam 8 Hoover Dam 26 Lake Havasu 11 Chemical changes in Lake Mead --- ---- - 26 Imperial Dam ---- - 12 Bill Williams River 27 Mineral burden of the lower Colorado River, 1926-65 - 12 Chemical changes in Lakes Mohave and Havasu ___ 27 Analysis of dissolved-solids loads 13 Diversion to Colorado River aqueduct 27 Analysis of ionic loads ____ - 15 Parker Dam to Imperial Dam 28 Average annual ionic burden of the Colorado River 20 Ionic accounting of principal irrigation areas above Ionic budget of the Colorado River from Lees Ferry to Imperial Dam - __ -------- 28 Imperial Dam, 1961-65 ____- ___ 22 General characteristics of Colorado River water below Lees Ferry 23 Imperial Dam Paria River 23 Ionic budgets for the Colorado River below Imperial Little Colorado River 24 Blue Springs --- 25 Dam and Gila River - 34 Unmeasured inflow from Lees Ferry to Grand Quality of surface water in the Salton Sea basin in Canyon 25 California Grand Canyon 25 Summary of conclusions 39 Bright Angel Creek 25 References ILLUSTRATIONS Page FIGURE 1 . -

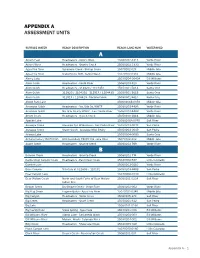

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED A Ackers East Headwaters - Ackers West 15060202-3313 Verde River Ackers West Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-3333 Verde River Agua Fria River Sycamore Creek - Bishop Creek 15070102-023 Middle Gila Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo Lake 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alder Creek Headwaters - Verde River 15060203-910 Verde River Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820 / 1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - Aravaipa Wild. Bndry 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arizona Canal (15070102) HUC boundary 15070102 - Gila River 15070102-202 Middle Gila Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River B Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bass Canyon Tributary at 322606 / 110131 15050203-899B San Pedro -

White Sands U.S

National Park Service White Sands U.S. Department of the Interior White Sands National Monument Lost and Found in the Grand Canyon By Ron McNeel, Volunteer Intepretive Park Ranger hen I first heard about the NPS I am Arizona born and raised. The WCentennial campaign to FIND Grand Canyon is the state’s pride. YOUR PARK, I was dubious about I went to college in Flagstaff at the slogan. Don’t we keep looking Northern Arizona University. As for the next park, and the next, while an undergraduate, with outdoorsy hoarding memories of those we’ve college buddies, I hiked into the already driven through, walked in, canyon four times down four different saddled up for, paddled down? In routes. The first trip took me down fact, bagged? the main Kaibab Trail, across the And the national parks are treasured Black Bridge to Phantom Ranch, and as public lands. How does the then back across the Silver Bridge, over the Colorado River, up the Bright possessive “your” figure in? Angel Trail. What names! Maybe it does in a newly nostalgic story like mine. I serendipitously On this raft trip, I would get to sail found a replacement slot on a raft under those same hand-crafted trip down the Colorado River bridges, built only for hikers and through the Grand Canyon. When mules. But on the trip’s first day, the I heard, in May, of an opening on rapid at Badger Creek would bounce an early July excursion, I snatched and bob me past the campsite of my at the chance. -

Pre-Hike Lodging Camping in the Canyon Activities HAVASUPAI

HAVASUPAI Best Time of Year How to Get There Most popular months to visit are March-October From Las Vegas McCarran International Airport – 3.5 hours/220 miles Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport – 4.5 hours/270 miles Activities Hiking – Guided hiking and interpretation on the trek into Havasupai as Backpacking - Guided backpacking and interpretation on the trek into well as to lesser known waterfall and canyon locations. Havasupai as well as to lesser known waterfall and canyon locations. Swimming – Swimming in the blue-green water of Havasu Creek at the Additional Activities – With our partners we can also book: base of exquisite waterfalls both popular and secluded. Helicopter Flights to and from Hualapai Hilltop Horseback Rides to and from Hualapai Hilltop Pre-Hike Lodging Camping in the Canyon Grand Canyon Caverns Inn - Located along iconic Route 66, Grand Havasu Creek - Relax at our comfortable horse supported base camp Canyon Caverns Inn is the closest lodging to “Hill Top”, the starting and and enjoy the streamside camping along the blue-green waters of ending point for the hike to Havasupai. This location offers easy access Havasu Creek. Drinking water and composting toilets are provided and to the trailhead and provides amenities such as a convenience market, our guides set up a solar shower within camp. free breakfast, a swimming pool, and more. We have been working with Grand Canyon Caverns Inn for over a decade and have long-standing business relationships with the staff. Hualapai Lodge - Located along historic Route 66 on the Hualapai Common spots we can take your guests from here & driving time: Reservation, this simple, low-rise hotel is 11.9 miles from the Grand Grand Canyon South Rim: 3.5 hours, Sedona: 3.5 hours, Lake Powell: 5 Canyon Caverns and a 1.5 hour drive from Hualapai Hill Top.