APPENDIX E Water Use and Dependency in the Mhlathuze Catchment: a Macro Economic and Sectoral Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Background Information Document: Basic Assessment for the Proposed Pongola Township Development on Portion 419 of the Farm No

ETC-Africa CC Po Box 522 Richards Bay 3900 Richards Bay South Africa Phone: +27 (72) 4760396 [email protected] www.etc-africa.com.za BACKGROUND INFORMATION DOCUMENT: BASIC ASSESSMENT FOR THE PROPOSED PONGOLA TOWNSHIP DEVELOPMENT ON PORTION 419 OF THE FARM NO. 61, PONGOLA, KWAZULU-NATAL WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF THIS DOCUMENT? The purpose of this document is to: Inform Interested and Affected Parties (I&APs) about the proposed project, and to invite them to participate; Provide a brief background on the proposed project; and Explain the aims and objectives of the Basic Assessment. WHAT IS PROPOSED? An application will been submitted to the KZN Department of Economic Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs on behalf of uPhongolo Local Municipality, Environmental Authorisation for a proposed township development within uPhongolo Local Municipality. The site is 19 hectares in area and is approximately 7 km (by road) from Pongola town. The township development will be comprised of: • High density housing (280 units) • Public open spaces; • A creche; • A place of worship (church); • A business center; • Associated infrastructure (roads, stormwater, sanitation, electricity) In terms of Listing Notice 1 (GNR R983) promulgated in 2014 under The National Environmental Management Act (Act No. 107 of 1998), EIA Regulations 2014, listed activities will be triggered by this development and therefore requires a Basic Assessment report to be submitted to KZN Department of Economic Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs. The listed activities triggered by the proposed development are as follows: Listing Notice 1: Activity 28; Residential, mixed, retail, commercial, industrial or institutional developments where such land was used for agriculture or afforestation on or after 01 April 1998 and where such development: (ii) will occur outside an urban area, where the total land to be developed is bigger than 1 hectare; Listing Notice 1. -

The Cholera Outbreak

The Cholera Outbreak: A 2000-2002 case study of the source of the outbreak in the Madlebe Tribal Authority areas, uThungulu Region, KwaZulu-Natal rdsn Edward Cottle The Rural Development Services Network (RDSN) Private Bag X67 Braamfontein 2017 Tel: (011) 403 7324 www.rdsn.org.za Hameda Deedat International Labour and Research Information Group (ILRIG) P.O. Box 1213 Woodstock 7915 Tel: (021) 447 6375 www.aidc.org.za/ilrig Edited by Dudley Moloi Sub-edited by Nicolas Dieltiens Funders: Municipal Services Project SOUTH AFRICAN MUNICIPAL WORKERS’ UNION Acknowledgements A special word of thanks to: Fieldworkers Dudu Khumalo and Sikhumbuso Khanyile from SAMWU KZN, for their help with the community interviews. And to our referees: Dr. David Hemson (Human Science Research Council) Dr. David Sanders (Public Health Programme, University of the Western Cape) Sue Tilley (Social Consultant) Stephen Greenberg (Social Consultant) Contents Executive summary 1 Section 1: Introduction 7 1.1 Objectives of the study 9 Section 2: Methodology 10 2.1 Research methods 10 2.1.1 Transepts 10 2.1.2 In-depth Interviews 11 2.1.3 Interviews in Ngwelezane 11 2.1.4 Interviews in the rural areas 12 2.1.5 Interviews with municipal officials 12 2.2 Limitations of the research 13 Section 3: The Policy Context 14 Section 4: The Geographic Context 16 4.1 A description of the area under Investigation 16 4.1.1 Introduction 16 4.1.2 Brief History 16 4.1.3 Demographic information 17 4.1.4 Economic Expansion 18 4.1.5 Climate & Disease 20 4.1.6 Water & Sanitation 20 4.2 Post-apartheid -

Challenges and Developments Facing SA Coal Logistics”

“Challenges and developments facing SA Coal Logistics” IHS Energy SA Coal Conference 1 February 2019 Mandisa Mondi, General Manager: Coal BU - Transnet Freight Rail Transnet Freight Rail is a division of Transnet SOC Ltd Reg no.: 1990/000900/30 An Authorised Financial 1 Service Provider – FSP 18828 Overview SA Competitiveness The Transnet Business and Mandate The Coal Line: Profile Export Coal Philosophy Challenges and Opportunities New Developments Conclusions Transnet Freight Rail is a division of Transnet SOC Ltd Reg no.: 1990/000900/30 2 SA Competitiveness: Global Reserves Global Reserves (bt) Global Production (mt) Despite large reserves of coal that remain across the world, electricity generation alternatives are USA 1 237.29 2 906 emerging and slowing down dependence on coal. Russia 2 157.01 6 357 European countries have diversified their 3 114.5 1 3,87 China energy mix reducing reliance on coal Australia 4 76.46 3 644 significantly. India 5 60.6 4 537 However, Asia and Africa are still at a level where countries are facilitating access to Germany 6 40.7 8 185 basic electricity and advancing their Ukraine 7 33.8 10 60 industrial sectors, and are likely to strongly Kazakhstan 8 33.6 9 108 rely on coal for power generation. South Africa 9 30.1 7 269 South Africa remains in the top 10 producing Indonesia 10 28 5 458 countries putting it in a fairly competitive level with the rest of global producers. Source: World Energy Council 2016 SA Competitiveness : Coal Quality Country Exports Grade Heating value Ash Sulphur (2018) USA 52mt B 5,850 – 6,000 14% 1.0% Indonesia 344mt C 5,500 13.99% Australia 208mt B 5,850 – 6,000 15% 0.75% Russia 149.3mt B 5,850 – 6,000 15% 0.75% Colombia 84mt B 5,850 – 6,000 11% 0.85% S Africa 78mt B 5,500 - 6,000 17% 1.0% South Africa’s coal quality is graded B , the second best coal quality in the world and Grade Calorific Value Range (in kCal/kg) compares well with major coal exporting countries globally. -

Ward 23 Has an Estimated Population of 10701 As Per Census 2011

WARD BASE PLAN 2017/2018 23 1 | P a g e TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 4 2. WARD VISION – DESIRED FUTURE .................................................................................................. 4 3. WARD CHALLENGIES – CURRENT REALITY ...................................................................................... 4 4. SIZE OF THE WARD .......................................................................................................................... 5 5. WARD COMMITTEE STRUCTURE ..................................................................................................... 5 5.1 War Room Representatives .................................................................................................... 6 6. DEMOGRAPHICS .............................................................................................................................. 7 6.1 Population ............................................................................................................................... 7 6.2 Age and Gender Profile ........................................................................................................... 8 6.3 Language ................................................................................................................................. 8 6.4 Age Groups in 5 years by Population group and Gender........................................................ 9 -

Umlalazi Strategic Planning Session

UMLALAZI STRATEGIC PLANNING SESSION INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLANNING Lizette Dirker IDP Coordination Business Unit INFORMANTS OF THE IDP SOUTH AFRICAN PLANNING SYSTEMS National Provincial Local District wide PGDS Vision 2030 DGDP (Vision 2035) (Vision 2035) National IDP PGDP Development 5 years Plan National Provincial Municipal Planning Planning Council Commission Commission WARD BASED SDGs SDGs PLANS “KZN as a prosperous Province with healthy, secure and skilled population, living in dignity and harmony, acting as a gateway to Africa and the World” Sustainable Development Goals AGENDA 2063 50 Year Vision • Agenda 2063 is a strategic framework for the socio-economic transformation of the continent over the next 50 years. It builds on, and seeks to accelerate the implementation of past and existing continental initiatives for growth and sustainable development Adopted in January 2015 • Adopted in January 2015, in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia by the 24th African Union (AU) Assembly of Heads of State and Government 10 Year implementation cycle • Five ten year implementation plan – the first plan 2014-2023 1. A prosperous Africa based on inclusive growth and sustainable 5. An Africa with a strong cultural development identity, common heritage, shared values and ethics 2. An integrated continent, politically united and based on the ideals of Pan-Africanism and the 6. An Africa whose development vision of Africa’s Renaissance is people-driven, relying on the potential of African people, especially its women and youth, and caring for children 3. An Africa of good governance, democracy, respect for human rights, justice and the rule of law 7. Africa as a strong, united and influential global player and partner 4. -

Ethembeni Cultural Heritage

ETHEMBENI CULTURAL HERITAGE Amafa aKwazulu-Natali 22 January 2016 195 Jabu Ndlovu Street Pietermaritzburg 3200 August Telephone 033 3946 543 [email protected] Attention Bernadet Pawandiwa Dear Ms Pawandiwa Application for Exemption from a Phase 1 Heritage Impact Assessment Proposed Expansion of Dolerite Borrow Pit Pogela Farm, Heatonville Ntambanana LM, King Cetshwayo DM, KwaZulu-Natal. Project Area and Project description1 Mr John Readman of Pogela Farm, Heatonville, wishes to expand the existing dolerite borrow pit on his farm to an area of 3.11 ha, for commercial utilisation. This proposed expansion requires the conducting of a Basic Assessment in terms of both NEMA and DMR regulations. The existing borrow pit lies adjacent to an abandoned single-quarters residential compound constructed by Tongaat-Hulett in 1994. It is Mr Readman’ intention to demolish all structures in the course of expansion activities for the borrow pit. Observations No graves are located or reported in the immediate precinct of the planned expansion and any associated plant and services proposed2. The compound buildings are utilitarian, in a state of disuse and of no intrinsic significance. They are due to be demolished. The Ntabanana and Heatonville farms were granted in compensation to returning service-men after WWI (1918) and WWII (1945).3 These farms have been under sugar cane production for at least the last 40 to 50 years4. 1 J. Readman, pers.comm to LO van Schalkwyk. 2 Ibid. 3 2016. Heritage Scoping Report for the Invubu-Theta 400 kV Transmission -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

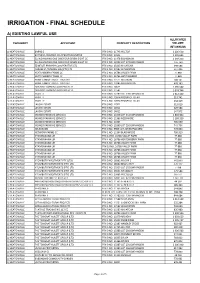

Irrigation - Final Schedule

IRRIGATION - FINAL SCHEDULE A) EXISTING LAWFUL USE ALLOCATED CATEGORY APPLICANT PROPERTY DESCRIPTION VOLUME (M 3/ANNUM) 1) HEATONVILLE BARNS D PTN 0 NO. 11745 HILLTOP 1 226 610 1) HEATONVILLE BAYANDA PRIMARY CO-OPERATIVE LIMITED PTN 0 NO. 11542 1 335 642 1) HEATONVILLE ELLINGHAM NO ONE ONE FOUR SEVEN EIGHT CC PTN 0 NO. 11478 ELLINGHAM 1 168 200 1) HEATONVILLE ELLINGHAM NO ONE ONE FOUR SEVEN EIGHT CC PTN 2 NO. 12922 LOT 272 EMPANGENI 155 760 1) HEATONVILLE EZIMTOTI PRIMARY CO-OPERATIVE LTD PTN 0 NO. 13313 MAJATCHA 698 584 1) HEATONVILLE FORUM SA TRADING 306 (PTY) LTD PTN 4 NO. 11582 WALLENTON 547 496 1) HEATONVILLE HEATONBERRY FARMS CC PTN 2 NO. 16786 VALLEY FARM 77 880 1) HEATONVILLE HEATONBERRY FARMS CC PTN 3 NO. 16786 HEATONBERRY 77 880 1) HEATONVILLE HUME FAMILY TRUST - TRUSTEES PTN 0 NO. 11571 BOLARUM 700 141 1) HEATONVILLE HUME FAMILY TRUST - TRUSTEES PTN 0 NO. 12085 MERCHISTON 478 183 1) HEATONVILLE ISIBUSISO FARMING AND PROJECTS PTN 0 NO. 14625 1 596 540 1) HEATONVILLE ISIBUSISO FARMING AND PROJECTS PTN 3 NO. 11582 1 074 744 1) HEATONVILLE KRAFTT F PTN 0 NO. 12280 LOT 239 EMPANGENI 1 012 440 1) HEATONVILLE KRAFTT F PTN 3 NO. 10974 PROSPECT ESTATE 310 741 1) HEATONVILLE KRAFTT F PTN 4 NO. 10974 PROSPECT ESTATE 234 419 1) HEATONVILLE LAVONI ESTATE PTN 0 NO. 12922 313 619 1) HEATONVILLE LAVONI ESTATE PTN 0 NO. 14014 529 584 1) HEATONVILLE LAVONI ESTATE PTN 0 NO. 14015 147 972 1) HEATONVILLE MONGO FARMING SERVICES PTN 0 NO. -

The Future of South African Coal: Market, Investment, and Policy Challenges

PROGRAM ON ENERGY AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Working Paper #100 January 2011 THE FUTURE OF SOUTH AFRICAN COAL: MARKET, INVESTMENT, AND POLICY CHALLENGES ANTON EBERHARD FREEMAN SPOGLI INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES FREEMAN SPOGLI INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES About the Program on Energy and Sustainable Development The Program on Energy and Sustainable Development (PESD) is an international, interdisciplinary program that studies how institutions shape patterns of energy production and use, in turn affecting human welfare and environmental quality. Economic and political incentives and pre-existing legal frameworks and regulatory processes all play crucial roles in determining what technologies and policies are chosen to address current and future energy and environmental challenges. PESD research examines issues including: 1) effective policies for addressing climate change, 2) the role of national oil companies in the world oil market, 3) the emerging global coal market, 4) the world natural gas market with a focus on the impact of unconventional sources, 5) business models for carbon capture and storage, 6) adaptation of wholesale electricity markets to support a low-carbon future, 7) global power sector reform, and 8) how modern energy services can be supplied sustainably to the world’s poorest regions. The Program is part of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University. PESD gratefully acknowledges substantial core funding from BP and EPRI. Program on Energy and Sustainable Development Encina Hall East, Room E415 Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6055 http://pesd.stanford.edu About the Author Anton Eberhard leads the Management Programme in Infrastructure Reform and Regulation at the University of Cape Town Graduate School of Business. -

Threatened Ecosystems in South Africa: Descriptions and Maps

Threatened Ecosystems in South Africa: Descriptions and Maps DRAFT May 2009 South African National Biodiversity Institute Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism Contents List of tables .............................................................................................................................. vii List of figures............................................................................................................................. vii 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 8 2 Criteria for identifying threatened ecosystems............................................................... 10 3 Summary of listed ecosystems ........................................................................................ 12 4 Descriptions and individual maps of threatened ecosystems ...................................... 14 4.1 Explanation of descriptions ........................................................................................................ 14 4.2 Listed threatened ecosystems ................................................................................................... 16 4.2.1 Critically Endangered (CR) ................................................................................................................ 16 1. Atlantis Sand Fynbos (FFd 4) .......................................................................................................................... 16 2. Blesbokspruit Highveld Grassland -

Development of a Strategic Corridor Plan for the Umhlathuze-Ulundi- Vryheid Secondary Corridor – ZNT 1970/2015 LG-14

Report Development of a Strategic Corridor Plan for the uMhlathuze-Ulundi- Vryheid Secondary Corridor – ZNT 1970/2015 LG-14 Milestone 5 Deliverable: Implementation and Phasing Plan KZN Cooperative Governance & Traditional Affairs: Client: LED Unit Reference: T&PMD1740-100-104R003F02 Revision: 02/Final Date: 24 July 2017 O p e n ROYAL HASKONINGDHV (PTY) LTD 30 Montrose Park Boulevard Montrose Park Village Victoria Country Club Estate Montrose Pietermaritzburg 3201 Transport & Planning Reg No. 1966/001916/07 +27 33 328 1000 T +27 33 328 1005 F [email protected] E royalhaskoningdhv.com+27 33 328 1000 W +27 33 328 1005 T Document title: Development of a Strategic Corridor Plan for the [email protected] F Secondary Corridor – ZNT 1970/2015 LG-14 royalhaskoningdhv.com+27 33 328 1000 E Document short title: SC1 Implementation & Phasing Plan +27 33 328 1005 W Reference: T&PMD1740-100-104R003F02 [email protected] T Revision: 02/Final royalhaskoningdhv.com+27 33 328 1000 F Date: 24 July 2017 +27 33 328 1005 E Project name: SC1 Corridor [email protected] W Project number: MD1740-100-104 royalhaskoningdhv.com T Author(s): Anton Martens (UPD), Bronwen Griffiths, Chris Cason, Lisa Higginson (Urban- F Econ), Nomcebo Hlophe, Rob Tarboton, Talia Feigenbaum (Urban-Econ) and E Andrew Schultz W Drafted by: Andrew Schultz Checked by: Date / initials: Approved by: Date / initials: Classification Open Disclaimer No part of these specifications/printed matter may be reproduced and/or published by print, photocopy, microfilm or by any other means, without the prior written permission of Royal HaskoningDHV (Pty) Ltd; nor may they be used, without such permission, for any purposes other than that for which they were produced. -

Curriculum Vitae Keagan Chase Kruger

CURRICULUM VITAE KEAGAN CHASE KRUGER Name of Firm: ACER (Africa) Environmental Consultants Name of Staff: Keagan Chase Kruger Profession: Environmental Consultant Date of birth: 27 April 1989 Years with firm: 4.5 years Nationality: South African RELEVANT PROJECT EXPERIENCE 2017: Dube Tradeport. The extension of the Tongaat Trunk Sewer Line, KwaZulu-Natal. [Environmental Compliance Officer]. 2017: Umzimvubu Local Municipality. Environmental Authorisation and associated permits/licenses for gravel access roads and concrete causeways near Mount Frere [Vegetation Assessment, Wetland Assessment and Water Use Licence Applications]. 2017: Umzimvubu Local Municipality. Environmental Authorisation and associated permits/licenses for gravel access roads and concrete causeways near Mount Ayliff [Vegetation Assessment, Vegetation Assessment, Wetland Assessment and Water Use Licence Applications]. 2017: Leo Mattioda. Environmental Authorisation and Associated Mining Permit for a Borrow Pit on Mr J Readman’s Farm near Heatonville [Vegetation Assessment, Vegetation Assessment, Wetland Assessment and Water Use Licence Applications]. 2017: Kevin Lawrie Trust. Environmental Authorisation for the establishment of a layer poultry farm near Mtubatuba. [Vegetation Assessment and Wetland Delineation and Functional Assessment]. 2016/17: Eskom Distribution Limited. Clocolan-Ficksburg 88 kV Power Line and Marallaneng Substation, Free State. [Environmental Assessment Practitioner services for amending the existing Environmental Authorisation and obtaining Water