Reconstructing Beethoven: Mauricio Kagel's Ludwig

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karlheinz Stockhausen: Works for Ensemble English

composed 137 works for ensemble (2 players or more) from 1950 to 2007. SCORES , compact discs, books , posters, videos, music boxes may be ordered directly from the Stockhausen-Verlag . A complete list of Stockhausen ’s works and CDs is available free of charge from the Stockhausen-Verlag , Kettenberg 15, 51515 Kürten, Germany (Fax: +49 [0 ] 2268-1813; e-mail [email protected]) www.stockhausen.org Karlheinz Stockhausen Works for ensemble (2 players or more) (Among these works for more than 18 players which are usu al ly not per formed by orches tras, but rath er by cham ber ensem bles such as the Lon don Sin fo niet ta , the Ensem ble Inter con tem po rain , the Asko Ensem ble , or Ensem ble Mod ern .) All works which were composed until 1969 (work numbers ¿ to 29) are pub lished by Uni ver sal Edi tion in Vien na, with the excep tion of ETUDE, Elec tron ic STUD IES I and II, GESANG DER JÜNGLINGE , KON TAKTE, MOMENTE, and HYM NEN , which are pub lished since 1993 by the Stock hau sen -Ver lag , and the renewed compositions 3x REFRAIN 2000, MIXTURE 2003, STOP and START. Start ing with work num ber 30, all com po si tions are pub lished by the Stock hau sen -Ver lag , Ket ten berg 15, 51515 Kürten, Ger ma ny, and may be ordered di rect ly. [9 ’21”] = dura tion of 9 min utes and 21 sec onds (dura tions with min utes and sec onds: CD dura tions of the Com plete Edi tion ). -

Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

452 ROBYNN STILWELL Joplin, Janis. 'Me and Bobby McGee' (Columbia, 1971) i_ /Mercedes Benz' (Columbia, 1971) 17- Llttle Richard. 'Lucille' (Specialty, 1957) 'Tutti Frutti' (Specialty, 1955) Lynn, Loretta. 'The Pili' (MCA, 1975) Expanding horizons: the International 'You Ain't Woman Enough to Take My Man' (MCA, 1966) avant-garde, 1962-75 'Your Squaw Is On the Warpath' (Decca, 1969) The Marvelettes. 'Picase Mr. Postman' (Motown, 1961) RICHARD TOOP Matchbox Twenty. 'Damn' (Atlantic, 1996) Nelson, Ricky. 'Helio, Mary Lou' (Imperial, 1958) 'Traveling Man' (Imperial, 1959) Phair, Liz. 'Happy'(live, 1996) Darmstadt after Steinecke Pickett, Wilson. 'In the Midnight Hour' (Atlantic, 1965) Presley, Elvis. 'Hound Dog' (RCA, 1956) When Wolfgang Steinecke - the originator of the Darmstadt Ferienkurse - The Ravens. 'Rock All Night Long' (Mercury, 1948) died at the end of 1961, much of the increasingly fragüe spirit of collegial- Redding, Otis. 'Dock of the Bay' (Stax, 1968) ity within the Cologne/Darmstadt-centred avant-garde died with him. Boulez 'Mr. Pitiful' (Stax, 1964) and Stockhausen in particular were already fiercely competitive, and when in 'Respect'(Stax, 1965) 1960 Steinecke had assigned direction of the Darmstadt composition course Simón and Garfunkel. 'A Simple Desultory Philippic' (Columbia, 1967) to Boulez, Stockhausen had pointedly stayed away.1 Cage's work and sig- Sinatra, Frank. In the Wee SmallHoun (Capítol, 1954) Songsfor Swinging Lovers (Capítol, 1955) nificance was a constant source of acrimonious debate, and Nono's bitter Surfaris. 'Wipe Out' (Decca, 1963) opposition to himz was one reason for the Italian composer being marginal- The Temptations. 'Papa Was a Rolling Stone' (Motown, 1972) ized by the Cologne inner circle as a structuralist reactionary. -

Transgressing the Wall. Mauricio Kagel and Decanonization of the Musical Performance

Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov Series VIII: Performing Arts • Vol. 13 (60) No. 2 - 2020 https://doi.org/10.31926/but.pa.2020.13.62.2.2 Transgressing the Wall. Mauricio Kagel and Decanonization of the musical performance Laurențiu BELDEAN1, Malgorzata LISECKA2 Abstract: The article discusses selected some musical concept by Maurcio Kagel (1931–2008), one of the most significant Argentinian composer. The analysis concerns two issues related to Kagel’s work. First of all, the composer’s approach to musical theatre as an artistic tool for demolishing a wall put in cultural tradition between a performer and a musical work – just like Berlin Wall which turned the politics paradigm in order to melt two political positions into one. Kagel’s negation of the structure’s coherence in traditional musical canon became the basis of his conceptualization which implies a collapse within the wall between the musical instrument and the performer. Aforementioned performer doesn’t remain in the passive role, but is engaged in the art with his whole body as authentic, vivid instrument. Secondly, this article concerns the actual threads of Kagel’s music, as he was interested in enclosing in his work contemporary social and political issues. As the context of the analyze the authors used the ideas of Paulo Freire (with his concept of the pedagogy of freedom) and Augusto Boal (with his concept of “Theater of the Oppressed”). Both these perspectives aim to present Kagel as multifaceted composer who through his avantgarde approach abolishes canons (walls) in contemporary music and at the same time points out the barriers and limitations of the global reality. -

KARLHEINZ STOCKHAUSEN Stockhausen

KARLHEINZ STOCKHAUSEN 1928-2007 Stockhausen German composer, widely acknowledged by critics as one of the most important, but also controversial composers of the 20th and early 21st centuries Another critic calls him "one of the great visionaries of 20th-century music" Stockhausen He is known for his groundbreaking work in electronic music, aleatory (controlled chance) in serial composition, and musical spatialization. Stockhausen Hymnen (1966-67) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hyx0I8_kTAQ One of the finest examples of formal tape music from the 1960’s 113 minutes long - four album sides when first released on record Gesang der Jünglinge (1955–56) Song of the Youths Routinely described as "the first masterpiece of electronic music” Seamlessly integrates electronic sounds with the human voice by means of matching voice resonances with pitch and creating sounds of phonemes electronically. The vocal parts were supplied by 12-year- old Josef Protschka. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UmGIiBfWI0E Scores Scores Scores Scores Aphex Twin Richard David James (born 18 August 1971), best known by his stage name Aphex Twin British electronic musician and composer. He has been described by The Guardian as "the most inventive and influential figure in contemporary electronic music" Aphex Twin's album Selected Ambient Works 85-92 was called the best album of the 1990s by FACT Magazine. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xw5AiRVqfqk Plastikman https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nsct-e-HVE0 Richard "Richie" Hawtin (born June 4, 1970) is an English-born Canadian electronic musician and DJ who was an influential part of Detroit techno's second wave of artists in the early 1990s A leading exponent of minimal techno since the mid-1990s. -

2013-Pressrelease-OKTOPHONIE

Park Avenue Armory Adds Two Performances for Karlheinz Stockhausen’s electronic masterpiece OKTOPHONIE, presented in a lunar environment created by Rirkrit Tiravanija Due to Overwhelming Demand Additional Performances Added, March 23 & 25 New York, NY—February 28, 2013—Due to overwhelming initial demand stemming from the 2013 artistic season announcement, Park Avenue Armory announced today the addition of two performances of the New York premiere of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s OKTOPHONIE. Part of Stockhausen’s magnum opus “Licht” (or “Light”) OKTOPHONIE is a trailblazing electronic music experience where the audience is surrounded by eight groups of loudspeakers, enveloping them in a sonic environment. OKTOPHONIE, which will be performed by one of his original collaborators Kathinka Pasveer, exemplifies Stockhausen’s work as a compositional pioneer who grappled with spatial music as he bent the rules and redefined the listening experience. Staging the work as the composer originally intended—in outer space—Rirkrit Tiravanija has been commissioned by the Armory to create a ritualized lunar experience, a floating seating installation within the Armory’s soaring drill hall that heightens the listeners’ octophonic experience and transports them to another realm. The audience will don white cloaks for the journey, carried along by the all- encompassing score, itself a meditation on the transformation from plunging darkness into blinding light. The Armory’s 2013 season will also include WS, a monumental installation by Paul McCarthy; The Machine, a play by one of Britain’s fastest rising young playwrights, Matt Charman, that chronicles Garry Kasparov’s 1997 chess game against IBM’s Deep Blue super-computer, a contest that set man against machine; Massive Attack V Adam Curtis, a new kind of imaginative experience conceived by Adam Curtis and Robert Del Naja mixing music, film, politics, and moments of illusion, performed by Massive Attack and special guests; and Robert Wilson’s powerful new staging of The Life and Death of Marina Abramović. -

New 2014–2017

Stockhausen-Verlag, 51515 Kürten, Germany www.karlheinzstockhausen.org / [email protected] NEW 2014–2017 New scores (can be ordered directly online at www.stockhausen-verlag.com): TELEMUSIK (TELE MUSIC) Electronic Music (English translation) ................................ __________ 96 ¤ (54 bound pages, 9 black-and-white photographs) ORIGINALE (ORIGINALS) Musical Theatre (Textbook) ..................................................... __________ 88 ¤ (48 bound pages, 11 black-and-white photographs) TAURUS-QUINTET for tuba, trumpet, bassoon, horn, trombone .................................... __________ 60 ¤ (folder with score in C, 10 bound pages, cover in colour with Stockhausen’s original drawing, plus performance material: 5 loose-leaf parts for tuba, trumpet, bassoon, horn in F and trombone) CAPRICORN for bass and electronic music ................................................................................ __________ 65 ¤ (60 bound pages, cover in colour) KAMEL-TANZ (CAMEL-DANCE) .............................................................................................. __________ 30 ¤ (of WEDNESDAY from LIGHT) for bass, trombone, synthesizer or tape and 2 dancers (20 bound pages, cover in colour) MENSCHEN, HÖRT (MANKIND, HEAR) .................................................................................. __________ 30 ¤ (of WEDNESDAY from LIGHT) for vocal sextet (2 S, A, T, 2 B) (24 bound pages, cover in colour with Stockhausen’s original drawing) HYMNEN (ANTHEMS) Electronic and Concrete Music – study -

Ulrich Buch Engl. Ulrich Buch Englisch

Stockhausen-Stiftung für Musik First edition 2012 Published by Stockhausen-Stiftung für Musik 51515 Kürten, Germany (Fax +49-[0] 2268-1813) www.stockhausen-verlag.com All rights reserved. Copying prohibited by law. O c Copyright Stockhausen-Stiftung für Musik 2012 Translation: Jayne Obst Layout: Kathinka Pasveer ISBN: 978-3-9815317-0-1 STOCKHAUSEN A THEOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION BY THOMAS ULRICH Stockhausen-Stiftung für Musik 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preliminary Remark .................................................................................................. VII Preface: Music and Religion ................................................................................. VII I. Metaphysical Theology of Order ................................................................. 3 1. Historical Situation ....................................................................................... 3 2. What is Music? ............................................................................................. 5 3. The Order of Tones and its Theological Roots ............................................ 7 4. The Artistic Application of Stockhausen’s Metaphysical Theology in Early Serialism .................................................. 14 5. Effects of Metaphysical Theology on the Young Stockhausen ................... 22 a. A Non-Historical Concept of Time ........................................................... 22 b. Domination Thinking ................................................................................ 23 c. Progressive Thinking -

A Symphonic Poem on Dante's Inferno and a Study on Karlheinz Stockhausen and His Effect on the Trumpet

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 A Symphonic Poem on Dante's Inferno and a study on Karlheinz Stockhausen and his effect on the trumpet Michael Joseph Berthelot Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Berthelot, Michael Joseph, "A Symphonic Poem on Dante's Inferno and a study on Karlheinz Stockhausen and his effect on the trumpet" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3187. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3187 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A SYMPHONIC POEM ON DANTE’S INFERNO AND A STUDY ON KARLHEINZ STOCKHAUSEN AND HIS EFFECT ON THE TRUMPET A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agriculture and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by Michael J Berthelot B.M., Louisiana State University, 2000 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2006 December 2008 Jackie ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dinos Constantinides most of all, because it was his constant support that made this dissertation possible. His patience in guiding me through this entire process was remarkable. It was Dr. Constantinides that taught great things to me about composition, music, and life. -

Sprechen Über Neue Musik

Sprechen über Neue Musik Eine Analyse der Sekundärliteratur und Komponistenkommentare zu Pierre Boulez’ Le Marteau sans maître (1954), Karlheinz Stockhausens Gesang der Jünglinge (1956) und György Ligetis Atmosphères (1961) Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt der Philosophischen Fakultät II der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Institut für Musik, Abteilung Musikwissenschaft von Julia Heimerdinger ∗∗∗ Datum der Verteidigung 4. Juli 2013 Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Auhagen Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Hirschmann I Inhalt 1. Einleitung 1 2. Untersuchungsgegenstand und Methode 10 2.1. Textkorpora 10 2.2. Methode 12 2.2.1. Problemstellung und das Programm MAXQDA 12 2.2.2. Die Variablentabelle und die Liste der Codes 15 2.2.3. Auswertung: Analysefunktionen und Visual Tools 32 3. Pierre Boulez: Le Marteau sans maître (1954) 35 3.1. „Das Glück einer irrationalen Dimension“. Pierre Boulez’ Werkkommentare 35 3.2. Die Rätsel des Marteau sans maître 47 3.2.1. Die auffällige Sprache zu Le Marteau sans maître 58 3.2.2. Wahrnehmung und Interpretation 68 4. Karlheinz Stockhausen: Gesang der Jünglinge (elektronische Musik) (1955-1956) 85 4.1. Kontinuum. Stockhausens Werkkommentare 85 4.2. Kontinuum? Gesang der Jünglinge 95 4.2.1. Die auffällige Sprache zum Gesang der Jünglinge 101 4.2.2. Wahrnehmung und Interpretation 109 5. György Ligeti: Atmosphères (1961) 123 5.1. Von der musikalischen Vorstellung zum musikalischen Schein. Ligetis Werkkommentare 123 5.1.2. Ligetis auffällige Sprache 129 5.1.3. Wahrnehmung und Interpretation 134 5.2. Die große Vorstellung. Atmosphères 143 5.2.2. Die auffällige Sprache zu Atmosphères 155 5.2.3. -

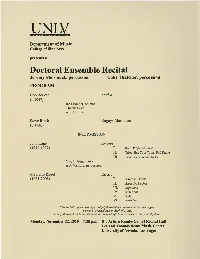

Doctoral Ensemble Recital Jeremy Meronuck, Percussion Luke Thatcher, Percussion PROGRAM

Department of Music College of Fine Arts presents a Doctoral Ensemble Recital Jeremy Meronuck, percussion Luke Thatcher, percussion PROGRAM Bob Becker Mudra (b.1947) Jack Steiner, soloist Charlie Gott A.J. Merlino Steve Reich Nagoya Marimbas (b.1936) INTERMISSION John Cage A mores (1912-1992) I. Solo: Prepared Piano II. Trio: ine Tom Toms, Pod Rattle ill. Trio: Seven Woodblocks Otto Ehling, piano A.J. Merlino, percussion Mauricio Kagel Rrrrrrr (1931-2008) I. Railroad Drama II. Ranz des Vaches III. Rigaudon IV. Rim Shot v. Ruff VI. Rutscher This recital is presented in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree Doctor ofMusical Arts in Applied Music. Jeremy Meronuck and Luke Thatcher are students ofDean Gronemeier and Timothy Jones. Monday, November 22,2010 7:30p.m. Dr. Arturo Rando-Grillot Recital Hall Lee and Thomas Beam Music Center University of Nevada, Las Vegas PROGRAM NOTES Mudra consists of music, which was originally composed to accompany the dance Mudra by choreographer Joan Phillips. Commissioned by INDE '90 and premiered in Toronto in March, 1990, as part of the DuMaurier Quay Works series, Mudra was awarded the National Art Centre Award for best collaboration between composer and choreographer. The music was subsequently edited and re-orchestrated as a concert piece for the percussion group NEXUS during May, 1990. Mudra is scored for marimba, vibraphone, songbells, glockenspiel, crotales, prepared drum and bass drum. Mudra was created, for the most part, using the "dance first" approach, in which the music is composed to fit pre-existing choreography. Thus, the rhythmic structure and overall form reflect the episodic and gestural character of the original choreography, which dealt with the conflict of traditional and modern issues in a multi-cultural urban society. -

MIXTUR - Karlheinz Stockhausen Prima Esecuzione Incontro Tra Elettronica E Orchestra Svizzera Domenica 10 Febbraio 2013 | 17.30 Auditorio RSI | Lugano

Luganomodern MIXTUR - Karlheinz Stockhausen prima esecuzione incontro tra elettronica e orchestra svizzera domenica 10 febbraio 2013 | 17.30 Auditorio RSI | Lugano concerto con opere di Karlheinz Stockhausen Ensemble 900 del CSI Direttore Arturo Tamayo Regia Regiadel suono del suono Pietro FabrizioLuca Congedo Rosso Ingegnere del suono Paolo Brandi conservatorio.ch +41(0)91 960 30 40 Biglietto 15 CHF LuganoCard, Amici del Conservatorio e Club di Rete Due 10 CHF Fino a 18 anni e studenti entrata gratuita mixtur – karlheinz stockhausen domenica 10 febbraio 2013 | 17.30 auditorio RSI | lugano K. Stockhausen Gesang der Jünglinge (1955 – 56) 14’ 1928 – 2007 per elettronica 30’ Mixtur Nr. 16 ½ (1967) per piccola orchestra, oscillatori e modulatori ad anello arturo tamayo _direzione francesco bossaglia _assistente direzione musicale pietro luca congedo _regia del suono paolo brandi _ingegnere del suono roberto mucchiut _progetto software Con il concerto di oggi vogliamo ricordare, nel quinto anniversario dalla sua scomparsa (3 dicembre 2007), la figura di Karlheinz Stockhausen, una delle principali personalità dell'avanguardia storica. La prima composizione del programma odierno è “Gesang der Jünglinge”; in essa, già nel lontano 1955-1956, Stockhausen mescola procedimenti e tecniche della musica elettronica (prodotto prevalentemente tedesco) con elementi della musica concreta "francese”. Fino ad allora i due ambiti erano sempre stati accuratamente separati in maniera quasi "religiosa”, mentre qui si fondono in un'opera di profonda spiritualità. La prima idea era stata quella di comporre una "Messa" - infatti il testo di cui il compositore si è servito è un testo biblico: la storia dal Libro di Daniele che ci racconta come i giovani Neduchadnezzar, Shadrach, Meshach e Abendnego, buttati in un forno ardente, miracolosamente protetti dal fuoco, cominciano a cantare le lodi a Dio. -

Holmes Electronic and Experimental Music

C H A P T E R 2 Early Electronic Music in Europe I noticed without surprise by recording the noise of things that one could perceive beyond sounds, the daily metaphors that they suggest to us. —Pierre Schaeffer Before the Tape Recorder Musique Concrète in France L’Objet Sonore—The Sound Object Origins of Musique Concrète Listen: Early Electronic Music in Europe Elektronische Musik in Germany Stockhausen’s Early Work Other Early European Studios Innovation: Electronic Music Equipment of the Studio di Fonologia Musicale (Milan, c.1960) Summary Milestones: Early Electronic Music of Europe Plate 2.1 Pierre Schaeffer operating the Pupitre d’espace (1951), the four rings of which could be used during a live performance to control the spatial distribution of electronically produced sounds using two front channels: one channel in the rear, and one overhead. (1951 © Ina/Maurice Lecardent, Ina GRM Archives) 42 EARLY HISTORY – PREDECESSORS AND PIONEERS A convergence of new technologies and a general cultural backlash against Old World arts and values made conditions favorable for the rise of electronic music in the years following World War II. Musical ideas that met with punishing repression and indiffer- ence prior to the war became less odious to a new generation of listeners who embraced futuristic advances of the atomic age. Prior to World War II, electronic music was anchored down by a reliance on live performance. Only a few composers—Varèse and Cage among them—anticipated the importance of the recording medium to the growth of electronic music. This chapter traces a technological transition from the turntable to the magnetic tape recorder as well as the transformation of electronic music from a medium of live performance to that of recorded media.