WEST BENGAL & SIKKIM Volume XVI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yearbook 1988

YEARBOOK 1988 A Directory of The General Conference, World Divisions, Union and Local Conferences and Missions, Educational Institutions, Food Companies, Health-Care Institutions, Media Center, Publishing Houses, Periodicals, and Denominational Workers Printed in the U.S.A. by the REVIEW AND HERALD PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION HAGERSTOWN, MD 21740 For the Office of Archives and Statistics GENERAL CONFERENCE OF SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTISTS 6840 EASTERN AVENUE, NORTHWEST WASHINGTON, D.C. 20012 Contents Preface and Statistics 4 Fundamental Beliefs of Seventh-day Adventists 5 Constitution and Bylaws 9 General Conference and Departments 15 Divisions: Africa-Indian Ocean 39 Eastern Africa 63 Euro-Africa 83 Far Eastern 107 Inter-American 155 North American 193 Health-Care Corporations 265 South American 269 South Pacific 303 Southern Asia 327 Trans-European 343 Middle East Union 361 South African Union 363 Southern Union (Africa) 366 China 371 The Seventh-day Adventist Church in the USSR 373 Institutions: Educational Institutions 377 Food Companies 481 Health-Care Institutions 489 Dispensaries 527 Retirement Homes and Orphanages 534 Media Centers 537 Publishing Houses 541 Periodicals 553 Necrology 568 Calendars of Special Days and Offerings 1988-1989 572 List of Countries With Their Organizational Locations 574 Telex Directory 576 Calendars 1988-1989 578 Index of Institutional Workers 579 Postal Abbreviations 658 Directory of Workers 659 General Index 1021 3 Preface to the 1988 Edition Scope of the Yearbook A world directory of the Seventh-day Adventist Church broke out in the vicinity. The first non-Protestant is given in the following pages. It includes the General Christian country entered was Russia, where an Adventist Conference and its international divisions, union and minister went in 1886. -

Sample Report-Madhya Pradesh.Pdf

Sample Checking Of Dise Data Of 2009-10 In Madhya Pradesh REPORT Submitted to The Commissioner Rajya Shiksha Kendra BHOPAL – 462001 Submitted by Dr. Sandeep Joshi Professor Madhya Pradesh Institute of Social Science Research (An ICSSR Institute) 6, Bharatpuri Administrative Zone, Ujjain – 456010 Acknowledgement The data collected through DISE is very important as it is used for policy formulation and programme implementation right from the grassroots level to the national level. Hence, the reliability and accuracy of the data is also of paramount importance. The present study of random sample checking of DISE Data of 2009-10 of Madhya Pradesh is an effort in that direction. It seeks to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of DISE data collection and the variations in the two sets of data, viz., DISE and Post Enumeration Survey (PES) using a structured schedule. I take this opportunity to thank Shri Manoj Jhalani IAS, Commissioner, Rajya Shiksha Kendra, Bhopal for instituting this study and extending financial support to carry out this fruitful academic endeavour in the State of Madhya Pradesh. I am also thankful to Shri Deepak Varma, State DISE In- charge, Rajya Shiksha Kendra, Bhopal for extending all possible support for successfully conducting the PES in four districts of Madhya Pradesh. The dedicated work of my research team (Ms. Preeti Kathuria, Mr. G.K. Rathore, Mr. Ashok Yadav, Mr. Neelesh Ambedkar, Mr. Praveen Gyani and Mr. Rajkumar Gyani) made it possible to complete the work within the stipulated time. I thank them all. I am also thankful to the Headmasters, BRCCs and CRCCs concerned along with district officials for their cooperation during the course of the field work in their respective districts. -

List of Candidates Found Eligible for the Written Examination to Be Held on 15.05.2016 for Recruitment to the Post of Wa‐Ii in Panchkula Region

LIST OF CANDIDATES FOUND ELIGIBLE FOR THE WRITTEN EXAMINATION TO BE HELD ON 15.05.2016 FOR RECRUITMENT TO THE POST OF WA‐II IN PANCHKULA REGION. NOTE:‐ • CANDIDATES DESIRING BENEFIT OF RESERVATION UNDER OBC CATEGORY MUST SUBMIT OBC CERTIFICATE AT THE TIME OF TYPING TEST WHICH WILL BE COMMUNICATED AFTER DECLARATION OF WRITTEN TEST RESULT IN THE PROFORMA ENCLOSED ALONGWITH DECLARATION AT ANNEXURE‐ I AND II RESPECTIVELY. • The ADMIT CARD shall be issued separately by post. DATE OF S.NO. NAME (S/SH./MS) BIRTH FATHER'S NAME 1 PANKAJ 24.11.1978 AMAR SINGH 2 SIMARANJEET SINGH 16.08.1990 RAVI BALWINDER SINGH 3 SANDEEP KUMAR 25.12.1995 CHANDI RAM 4 KAVITA 9.08.1991 CHANDI RAM 5 SUNIL KUMAR 10.02.1993 GURDEV SINGH 6 SUKHWINDER SINGH 06.04.1989 MAAN SINGH 7 RANJANA 15.11.1991 ASHOK KUMAR 8 NITIN KUMAR 8.10.1990 ASHOK KUMAR 9 KAPIL KUMAR 6.02.1990 BRIJ MOHAN 10 SURESH KUMAR 15.02.1996 CHANDER PAL 11 RAVI SHANKAR 5.01.1994 CHET RAM 12 KOMAL 30.06.1993 HARBANS LAL 13 NAVEEN KUMAR 15.08.1990 KULDEEP SINGH 14 RAHUL KALYAN 21.09.1990 JAGDISH CHAND 15 SUKHWINDER SINGH 29.03.1994 HARBANS SINGH 16 SACHIN 21.04.1988 JAGDISH CHAND 17 DALIP KUMAR 13.10.1989 RADE SHAM 18 KAMALDEEP BISIYER 29.09.1993 VIRBHAN BISIYER 19 KULDEEP SHARMA 4.08.1993 KRISHAN SHARMA 20 NAND KUMAR RAJENDRA BHISE 1.06.1989 RAJENDRA S BHISE 21 AJAY KUMAR 2.05.1993 RAM NAGEENA 22 PARDEEP SINGH 10.12.1990 AMARJIT SINGH 23 JAYDEEP YADAV 26.11.1990 PURSHOTAM LAL YADAV 24 SHANKAR 20.8.1997 ARJUN SINGH 25 PRASOON KUMARI 26.01.1990 VINOD KUMAR 26 VIJAY KUMAR 21.09.1990 PRABHAT SINGH 27 AKSHAY -

Nissionary SOCIETY

KiuillLiii JNÜAL REPORT OF THE /niSSIONaRY SOCIETY OF THE M e t h o d ist E p isc o p a l C h u rch . For the Y ear 1898. Cable Address, Missions. IF’IFl.IlKrTETD FO R . T H E SO C IE T Y , 1 5 0 FIFTH AVENUE, N E W Y O R K . 1 8 9 9 , Yale Divinity library New Haven, Conn. N e & CONTEIS í-i v . $ o - 2 3 PAGE ACT OF INCORPORATION.................................... ........................................................... 393 ANNUAL REPORT (EIGHTIETH)........................................................ 7 ANNUAL REPORT OF TREASURER AND ASSISTANT TREASURER ....... 12 ANNUITY ACCOUNT............................................................................................................ il APPORTIONMENT OF MONEYS TO BE RAISED DURING THE YEAR 1899 15 APPROPRIATIONS OF THE MISSIONARY SOCIETY FOR 1899....................... 19 APPROPRIATIONS OF THE W. F. M. S. FOR 1899................................................. 385 APPROPRIATIONS OF THE W. H. M. S. FOR 1899................................................ 385 APPROPRIATIONS TO MISSIONS AND CONFERENCES, 1890-1899................ 388 BY-LAWS OF THE BOARD OF MANAGERS............................................................. 403 CONSTITUTION..................................................................................................................... 399 CONTRIBUTIONS AND AVERAGE FOR TEN YEARS......................................... 386 DIRECTORY OF FOREIGN MISSIONARIES.............................................................. 362 DISBURSEMENTS OF THREE METHODIST MISSIONARY -

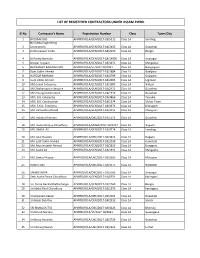

Contractor List.Xlsx

LIST OF REGISTERED CONTRACTORS UNDER ASSAM PWRD Sl No Contractor’s Name Registration Number Class Town/City 1 SRI DIPAK DAS APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/5311 Class 1A Sorbhog M/S Deka Engineering 2 Construction APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/2452 Class 1A Guwahati 3 Sri Dhaneswar Kalita APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/2150 Class 1A Rangia 4 Sri Prodip Bordoloi APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/14900 Class 1A Sivasagar 5 Anowar Hussain APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/3671 Class 1A Mangaldoi 6 DHANANJAY BASUMATARY APWRD/R/1A/ST/2017‐18/4814 Class 1A Bongaigaon 7 Giyas Uddin Ahmed APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/2684 Class 1A Goalpara 8 HAFIZUR RAHMAN APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/4799 Class 1A Goalpara 9 Isam Uddin Ahmed APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/2005 Class 1A Jagiroad 10 M/S Jonali Enterprise APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/2987 Class 1A Nalbari 11 M/S Mahamaya Enterprise APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/2471 Class 1A Guwahati 12 M/S Young Construction APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/1915 Class 1A Guwahati 13 M/S. B.B. Enterprise APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/3866 Class 1A Tinsukia 14 M/S. B.K. Construction APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/1574 Class 1A Silchar Town 15 M/S. S.K.D. Enterprise APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/2373 Class 1A Dibrugarh 16 Md. Alimuddin Ahmed APWRD/R/1A/GEN/2017‐18/2015 Class 1A Changsari 17 Md. Habibur Rahman APWRD/R/1A/OBC/2017‐18/1171 Class 1A Guwahati 18 Md. -

Koraput District As on 02.03.2019

TOTAL NBW LIST OF KORAPUT DISTRICT AS ON 02.03.2019 SL Name of the Address of the NBW REF. Father's Name Case Ref. NO. Warrantee Warrantee 1-DASMANTPUR PS 1 TR-53/2014 Ratha Khosla Purna Khosala K.Bedapadar TR-53/2014 2 CR-05/2014 Ajit Bagha Jagat Ch.Bagh Girligumma CR-05/2014 3 CT-27 /14 Tileswar Manenga Kartika Manenga Biriguda CT-27 /14 4 TR-53/2014 Mansa Khosala Purna Khosala Chikamba TR-53/2014 5 SC-20/12 Ramesh Kuldip Dillip Kuldip Jamur SC-20/12 6 CT-133/14 Krutibas Muduli Daitari Muduli Litiguda CT-133/14 7 GR-246/13 Ajaya Khosala Purna Khosala S.Totaguda GR-246/13 8 GR-565/02 Pitabash Bisoyi Udhaba Bisoyi Naranguda GR-565/02 9 GR-237/07 Dhaneswar Muduli Keshaba Muduli S.Totaguda GR-237/07 W/O-Ghanshyama 10 GR-63/02 Harshamanio Bisoyi Kaliamba GR-63/02 Bisoyi 11 GR-265/09 Santosh Turuk Iswar Turuk Pindapadar GR-265/09 12 GR-229/12 Krushna Ch.,Kansari Rama Kansari Dasamantpur GR-229/12 13 GR-837/15 Salman Khura Ananta Khura Dasamantpur GR-837/15 14 GR-395/04 Bhaskar Khura Rama Khura Kitesh GR-395/04 15 GR-184/13 Sahadeba Sagar Hari Sagar Maligaon GR-184/13 16 GR-104/96 Gobardhan Khosala Chandramani Khosla Girligumma GR-104/96 GR-357 Praphula Mani W/o-Choudhury 17 Kuntesh GR-357 (A)/16 (A)/16 Kandhapan Kandhapan 18 GR-111/09 Hemanta Mohanandia Krishna Mohanandia Giriligumma GR-111/09 19 GR-988/02 Kora Disari Luku Disari Tikarpada GR-988/02 20 GR-100/11 Nanda Kishor Khura Hari Khura Chandabada GR-100/11 21 GR-100/11 Simanchal Saunta Muga Saunta Kanjariguda GR-100/11 22 GR-242/03 Pana Kulusika W/o-Chinku Kulusika K.Dandabada GR-242/03 -

The Beyond Heroes Roleplaying Game Book I: the Player's Guide

1 The Beyond Heroes Roleplaying Game Book XXIV: The Book of Artifacts Writing and Design: Marco Ferraro The Book of Artifacts Copyright © 2020 Marco Ferraro All Rights Reserved This is meant as an amateur free fan production. Absolutely no money is generated from it. Wizards of the Coast, Dungeons & Dragons, and their logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast LLC in the United States and other countries. © 2019 Wizards. All Rights Reserved. Beyond Heroes is not affiliated with, endorsed, sponsored, or specifically approved by Wizards of the Coast LLC. Contents Foreword 3 Buying Magical Items 3 Magic; rare or common? 4 Researching Magical Items 4 The Nature of Magical Fabrication 5 Scrolls and Potions 7 Creating other magical items 10 Recharging Magical Items 12 Destroying Magical Items 13 Artifacts and Relics 13 Magic Item Quick Roll Table 18 Arcane Artifact Quick Roll Table 22 Arcane Vehicle Quick Roll Table 24 Arcane Architecture Quick Roll Table 28 Mystical Materials 33 Future Materials 37 Normal Materials 37 Modern Armour 40 Materials from other universes 40 Armour Materials Table 47 Beyond Heroes Artifacts 51 DC Universe Artifacts 59 Marvel Universe Artifacts 93 Artifacts from other Comic Universes’ 119 Moorcock Artifacts 125 Dungeons and Dragons Artifacts 131 Folklore Artifacts 137 2 Intelligent creatures, on the other hand, Foreword tend to value magical items above other The Beyond Heroes Role Playing Game items of treasure. They recognize such is based on a heavily revised derivative items for what they are (unless the item version of the rules system from is very well disguised or unique) and Advanced Dungeons and Dragons 2nd take them. -

Demonetization Stalls

www.theindianpanorama.com VOL 10 ISSUE 45 ● NEW YORK ● NOV 18 - NOV 24, 2016 ENQUIRIES: 646-247-9458 ● PRICE 40 CENTS YEARS DEMONETIZATION STALLS Parliament: Ruckus in Lok Sabha, Speaker adjourns House Guesses galore about Donald Chaotic scenes witnessed in both Houses of Parliament over Trump's Cabinet-in-waiting but scrapping of Rs1,000 and Rs500 notes only Trump knows who will be in NEW DELHI (TIP): Both Houses Rudy Giuliani, Jeff of parliament were adjourned on Sessions, Nikki Thursday, November 17, as opposition lawmakers continued Haley, Lt. Gen. their attack on the government over Michael Flynn are the impact of its ban on 500 and 1000 favorites; Gingrich, rupee notes. Today was the second Ben Carson not day of the winter session. Union finance minister Arun Jaitley later inclined As President-Elect Donald rejected all demands of the NEW YORK (TIP): As Trump attempts to cobble opposition. President-Elect Donald Trump together an efficient In the Rajya Sabha or Upper vets his prospects, a mix of cabinet, the media is rife House, where a debate on loyalists and others has with speculations demonetization has been on since emerged. contd on Page 32 Wednesday, the opposition shouted slogans demanding that Prime Minister Narendra Modi come to the Indian American Community house, listen to debate and respond to their questions. It's a stalemate, with Congress leader Mallikarjun Kharge, SP chief Mulayam Singh Yadav and other MPs in the Leader Dilip Chauhan honored the government refusing to give in to Lok Sabha during the winter session of Parliament on Thursday, November 17. -

A Work and Its Shapers the Most High Scripture of the Rectifying Methods

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ASU Digital Repository A Work and its Shapers The Most High Scripture of the Rectifying Methods of the Three Heavens in Early Medieval China by Timothy Charles Swanger A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved January 2019 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee Stephen Bokenkamp, Chair Robert Ford Campany Huaiyu Chen Young Oh Stephen West ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2019 ABSTRACT Religions, following Max Müller, have often been seen by scholars in religious studies as uniform collections of beliefs and practices encoded in stable “sacred books” that direct the conduct of religious actors. These texts were the chief focus of academic students of religion through much of the 20th century, and this approach remains strong in the 21st. However, a growing chorus of dissidents has begun to focus on the lived experience of practitioners and the material objects that structure that experience, and some textual scholars have begun extending this materialist framework to the study of texts. This dissertation is a contribution in that vein from the field of Daoist studies. Now split between two separate texts, the Most High Scripture of the Rectifying Methods of the Three Heavens began as a 4th-century collection of apocalyptic predictions and apotropaic devices designed to deliver a select group of Chinese literati to the heavens of Highest Clarity. Later editors during the early medieval period (ca. 220-589 CE) took one of two paths: for their own reasons, they altered the Rectifying Methods to emphasize either the world’s end or its continuation. -

Transport Management Service Office, Hetauda Bagmati Province Hetauda, Makawanpur

Province Government Ministry of Physical Infrastructure Development Transport Management Service Office, Hetauda Bagmati Province Hetauda, Makawanpur Driving License (Smart Card) Received and Distribution Record 1st Lot S.No. Card Holder's Name License Number Remarks 1 PRAKASH CHAULAGAIN 02-05-00670575 2 NARAYAN PAUDEL 02-05-00694009 LICENSERENEWAL 3 OM SAGAR RAI 01-06-00072678 LICENSERENEWAL 4 AJIT PANT 02-05-00693056 LICENSERENEWAL 5 AMAR BAHADUR DARAI 02-05-00693551 LICENSERENEWAL 6 AMAR JYOTI THAPA 02-05-00693491 LICENSERENEWAL 7 SURYA BAHADUR PRAJA 02-05-00693535 LICENSERENEWAL 8 SHREEKRISHNA TIMALSINA 01-06-00293893 LICENSERENEWAL 9 KRISHNA BAHADUR SHRESTHA 02-05-00695377 LICENSERENEWAL 10 SANTOSH SHRESTHA 01-06-00695597 LICENSERENEWAL 11 TIKA RAM DHAKAL 02-05-00695364 LICENSERENEWAL 12 BIR BAHADUR BAL 02-05-00696272 LICENSERENEWAL 13 BIKASH RAJ NEUPANE 02-05-00694460 LICENSERENEWAL 14 LOK NATH DHUNGANA 01-08-00001064 LICENSERENEWAL 15 DIPAK PRASAD UPRETI 02-05-00692429 LICENSERENEWAL 16 RAMKRISHNA GAUTAM 02-05-00692411 LICENSERENEWAL 17 PRATAP SINGH CHHETRI 02-05-00692422 LICENSERENEWAL 18 BIR BAHADUR LO 02-05-00692384 LICENSERENEWAL 19 Khyam Prasad Upreti 02-05-00456078 LICENSERENEWAL 20 LAL BAHADUR ACHARYA 02-05-00692909 LICENSERENEWAL 21 NAR BAHADUR BISTA 02-05-00687126 LICENSERENEWAL 22 SANTOSH SAPKOTA 02-05-00687106 LICENSERENEWAL 23 BUDDHA BAL 02-05-00687659 LICENSERENEWAL 24 MACHHINDRA BARTAULA 02-05-00687708 LICENSERENEWAL 25 DHRUBA PRASAD BIDARI 02-05-00688051 LICENSERENEWAL 26 DURGA NATH RIJAL 02-05-00688602 LICENSERENEWAL -

“A Missiological Critique of the World Council Of

“A MISSIOLOGICAL CRITIQUE OF THE WORLD COUNCIL OF CHURCHES’ NOTION OF JUST PEACE: ITS IMPLICATION AND CONTEXTUAL RELEVANCE FOR OVERCOMING VIOLENCE AND PEACEBUILDING IN THE MULTI-RELIGIOUS COMMUNITY OF JOS, NIGERIA” By Lesmore Gibson Ezekiel Submitted in Fulfilment of the Academic Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Practical Theology) At the School of Religion, Philosophy and Classics University of KwaZulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg Supervisor: Professor Roderick Hewitt December 2015 i Declaration As required by University regulations, I hereby certified that this thesis has not been presented for the award of a degree or diploma in any University or any other institution and also affirm that to the best of my knowledge, the thesis is my original work and contains no material previous published or written by another person, except where due reference is made within the text of the thesis. ------------------------------------------------------- Lesmore Gibson Ezekiel December 2015 As candidate’s Supervisor, I hereby approve this thesis for submission ------------------------------------------------------- Professor Roderick Hewitt December 2015 ii Dedication This work is dedicated to all people regardless of religious persuasion, ideological proclivity, cultural affinity, social status and political affiliation strive and intentionally work for the cause Justice and Peace all around the world. iii Acknowledgements My gratitude goes to God of life who has enabled me to go through this journey in good health and sound mind despite the challenges encountered. My profound appreciation is to my soul-mate, the love of my life, my dearest wife, Rhoda for her resilience, courage and inspiration during the cause of this academic exploration. She remains an invaluable gift to me. -

CONSOLIDATED DAILY ARREST REPORT DATED 30.07.2021 (Part-II) SL

CONSOLIDATED DAILY ARREST REPORT DATED 30.07.2021 (Part-II) SL. No Name Alias Sex Age Father/ Address PS of District/PC of Ps Name District/PC Name of Case/ GDE Ref. Accused Spouse residence residence Accused Name 3001 Bittu M 23 Manotosh Kismatdapat PS: Hilli Hilli Dakshin Dinajpur Hilli Dakshin Dinajpur Hilli PS GDE No. 1237 Mohanta Mohanta Dist.: Dakshin Dinajpur 3002 Amal M 26 Misto Malo Kismatdapat PS: Hilli Hilli Dakshin Dinajpur Hilli Dakshin Dinajpur Hilli PS GDE No. 1237 Malo Dist.: Dakshin Dinajpur 3003 Mahadev M 38 Lt. Sunil Purba Kismatdapa PS: Hilli Dakshin Dinajpur Hilli Dakshin Dinajpur Hilli PS GDE No. 1237 Mohanta Mohanta Hilli Dist.: Dakshin Dinajpur 3004 Sajal Paul M 25 Lt. Kismatdapat PS: Hilli Hilli Dakshin Dinajpur Hilli Dakshin Dinajpur Hilli PS GDE No. 1237 Ramanikant Dist.: Dakshin Dinajpur a Paul 3005 Utpal M Nimai BDO office more PS: Gangarampu Dakshin Dinajpur Gangarampur Dakshin Dinajpur Gangarampur PS GDE No. 1603 Biswas Biswas Gangarampur Dist.: r Dakshin Dinajpur 3006 Baidya M Dhiren Roy Dhaldighi Uttar Para Gangarampu Dakshin Dinajpur Gangarampur Dakshin Dinajpur Gangarampur PS GDE No. 1603 Roy PS: Gangarampur r Dist.: Dakshin Dinajpur 3007 Shayam M Chandan Padma pukur PS: Gangarampu Dakshin Dinajpur Gangarampur Dakshin Dinajpur Gangarampur PS GDE No. 1607 Sarkar Sarkar Gangarampur Dist.: r Dakshin Dinajpur 3008 Prasenjit M Ajay Subhash Pally PS: Gangarampu Dakshin Dinajpur Gangarampur Dakshin Dinajpur Gangarampur PS GDE No. 1607 Barman Barman Gangarampur Dist.: r Dakshin Dinajpur 3009 Ujjal M Lt. Chirup Shibbari PS: Gangarampu Dakshin Dinajpur Gangarampur Dakshin Dinajpur Gangarampur PS GDE No. 1607 Sarkar Sarkar Gangarampur Dist.: r Dakshin Dinajpur 3010 Goutam M Lt.