Undergraduate Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oversight Hearing Committee on Resources Us House

TRIBAL PROPOSALS TO ACQUIRE LAND-IN-TRUST FOR GAMING ACROSS STATE LINES AND HOW SUCH PROPOSALS ARE AFFECTED BY THE OFF-RESERVATION DIS- CUSSION DRAFT BILL. OVERSIGHT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON RESOURCES U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION Wednesday, April 27, 2005 Serial No. 109-9 Printed for the use of the Committee on Resources ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/house or Committee address: http://resourcescommittee.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 20-969 PS WASHINGTON : 2005 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 13:13 Aug 02, 2005 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 J:\DOCS\20969.TXT HRESOUR1 PsN: HRESOUR1 COMMITTEE ON RESOURCES RICHARD W. POMBO, California, Chairman NICK J. RAHALL II, West Virginia, Ranking Democrat Member Don Young, Alaska Dale E. Kildee, Michigan Jim Saxton, New Jersey Eni F.H. Faleomavaega, American Samoa Elton Gallegly, California Neil Abercrombie, Hawaii John J. Duncan, Jr., Tennessee Solomon P. Ortiz, Texas Wayne T. Gilchrest, Maryland Frank Pallone, Jr., New Jersey Ken Calvert, California Donna M. Christensen, Virgin Islands Barbara Cubin, Wyoming Ron Kind, Wisconsin Vice Chair Grace F. Napolitano, California George P. Radanovich, California Tom Udall, New Mexico Walter B. Jones, Jr., North Carolina Rau´ l M. Grijalva, Arizona Chris Cannon, Utah Madeleine Z. Bordallo, Guam John E. -

Place Names Beginning with the Letter G

, ·,,~ .' V GADBERRY (Adair Co.): ~hae~/b~r/eil (Columbia). All that .. »J~ " , ' , remains of this hamlet on KY 704, less,than 3 air miles s of .. ,J, , '. " "7- , F Columbia, ,is the Smith Chapel Church. Before, the Ci\til War , ..; , , , " a community here is said to have been called Butter Pint. Joe Creason' relates the tCl.le of a small boy who "had been ·, ;.. " sent to a neighbor's'house to'g(3t butter. 'H ow much do you' ,J '!! . ,.' ~~ . ,'.:: want?' he was asked. 'Oh,' the boy replied, 'I gl,less about 0' .• '. , , ~':~'-: ', .. ,.. , .:, a pint. '" The post off5.ce. was established as Gadberry on .~ .... :. ,', ~ ;:-" Sept. 24, .1884 with Finus Hurt, postmaster, ·and named for . " "" pioneer settler Jalnes Gadberry. The community failed to .. ' ., .... ,_. ,;- survite the closing of its remaining store shortly after the ,," Second World War though the post office continued until 1958., (Joe Creason "4th Plas's' Post ·OfNce· Going, Going ••• " LCJ, l " , , 6/29/1958, Sec. 4, P. lll-~ 3..-"1. i " .'. ~ ~., . t . s, . , , ~ .. '-',~ ~ , " , . • . " " " "'" , , - \\ . , , . :. ..;.;.; , " . • ,." . " , " " " , , , " ~ .. ,~ ·t , ., , .. '. " ! ;. , 'r; • ''<' - .'~' " ,: :.;? ~\: 'I; , j., ..:1, •••• ., , - '. ~INESVILLE (Allen CO.)I [ghanz/vih!1 (Scottsville). This community with extinct post office on Big Difficult Creek, 4 miles s of its union with the Barren River and 5~ air miles n of Scottsville, may be at or near the site of a log home built in 1814 by John Caruthers. From then nothing is known of the place until 1846 when Samuel' B. Gaines, a Virginian, arrived from nearby Port Oliver where he had a store, On July 1st of the following year, he established a post offfice and founded the Gainesville community which he named for him- self. -

History of the Glen Family of South Carolina and Georgia

A History of The Glen Family of South Carolina and Georgia BY J.G.B.BULLOCH,M.U November 1923. PREFACE In writing this history of the Glen family, the author is much indebted to the researches of Thomas Allen Glenn, Esq., through whose efforts so much has been gleaned of the family who were descended from the ancient feudal Barons of Ren frew, Scotland. Many thanks are also due to my friend Doctor Arthur Adams of Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut, who has rendered such invaluable aid to me. Some of the family went from Scotland to Ireland, thence to Pennsylvania and some settled in Delaware, while another branch went from Linlithgow and settled in South Carolina. William Glen may have gone from Linlithgow via Pennsyl vania, but, at any rate we find him in South Carolina as early as 1738. His younger son, John Glen, went to Georgia before 1776, and rose to be an important man in that colony. Some years ago my cousin, Mrs. Edwin R. Warrington, of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, sent me a history of the Glens of Scotland, part of which is herein included, and it was published in my history of "the Bulloch Family and Connections." Since that time the author has had access to a valuable contribution by Thomas Allen Glenn, of the Glens, published in the Penn sylvania Magazine of History and Biography, which I have freely consulted and from which I have taken much of that relating to the earlier history of the Glens, of Scotland. The services rendered by the Glens both in Scotland and in America to the country, show that they have occupied posi tions of importance. -

OCTOBER TERM 1994 Reference Index Contents

jnl94$ind1Ð04-04-96 12:34:32 JNLINDPGT MILES OCTOBER TERM 1994 Reference Index Contents: Page Statistics ....................................................................................... II General .......................................................................................... III Appeals ......................................................................................... III Arguments ................................................................................... III Attorneys ...................................................................................... III Briefs ............................................................................................. IV Certiorari ..................................................................................... IV Costs .............................................................................................. V Judgments and Opinions ........................................................... V Original Cases ............................................................................. V Records ......................................................................................... VI Rehearings ................................................................................... VI Rules ............................................................................................. VI Stays .............................................................................................. VI Conclusion ................................................................................... -

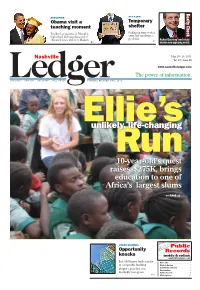

Unlikely, Life-Changing

EDUCATION Obama visit a teaching moment President’s appearance at Memphis high school facilitates discussion of education issues with Gov. Haslam. Nashville GET A JOB! Temporary Davi P3 shelter LedgerDson • Dickson • Picking up temp work is often, but not always, a cheatham • Williamson formerly good idea. Check Realty P 2 Richard Courtney’s real estate wisdom now appearing weekly WESTVIEW since 1978 The power of information.May 20 - 26, 2011 E www.nashvilleledger.com Vol. 37 | Issue 20 unlikely,llie’s life-changing Page 13 Dec.: Dec.: Keith Turner, Ratliff, Jeanan Mills Stuart, Resp.: Kimberly Dawn Wallace, Atty: Mary C Lagrone, 08/24/2010, 10P1318 In re: Jeanan Mills Stuart, Princess Angela Gates, Run Jeanan Mills Stuart, Princess Angela Gates,Dec.: Resp.: Kim Prince Patrick, Angelo Terry Patrick, Gates, Atty: Monica D Edwards, 08/25/2010, 10P1326 In re: Keith Turner, TN Dept Of Correction, www.westviewonline.com TN Dept Of Correction, Resp.: Johnny Moore,Dec.: Melinda Atty: Bryce L Tomlinson, Coatney, Resp.: 10-year-old’s quest Pltf(s): Rodney A Hall, Pltf Atty(s): n/a, 08/27/2010, 10P1336 In re: Kim Patrick, Terry Patrick, Pltf(s): Sandra Heavilon, Resp.: Jewell Tinnon, Atty: Ronald Andre Stewart, 08/24/2010,Dec.: Seton Corp 10P1322 raises $275K, bringsInsurance Company, Dec.: Regions Bank, Resp.: Leigh A Collins, In re: Melinda L Tomlinson, Def(s): Jit Steel Transport Inc, National Fire Insurance Company, Elizabeth D Hale, Atty: William Warner McNeilly, 08/24/2010, Def Atty(s): J Brent Moore, 08/26/2010, 10C3316 10P1321 Dec.: Amy -

Adair County, Kentucky

THE POST OFFICES OF ADAIR COUNTY, KENTUCKY On its organization on December 11, 1801 Adair, Kentucky's forty 1 fourth county, acquired 780 square miles from its sole parent Green County. It proceeded to lose thirty square miles to Wayne County in March 1804, gain ten square miles from Cumberland County in December of that year, lose 200 hundred square miles toward the creation of Russell County in April 1826 and another fifty square miles to Casey County in December 1827 . In 1843 it gained a small area from Barren County to accommodate a local landowner, lost a negligible amount to Casey in 1844 and eighty square miles toward the creation of Met calfe County in May 1860. It lost 1 another ten square miles to Metcalfe in 1861. The population of its current 407 square miles peaked at 18 ,566 in 1940. By 1970, however, it had dropped to 13,000 but rose s l ightly to 15,360 in 19~0 and 15 ,575 1n 2004. The county was named for General John Adair (1757-1840) who commanded Kentucky troops in the Battle of New Orleans (1815) and later became Kentucky's eighth governor (1820-24). He then served his state in the U.S. Senate (1825-31) and the U.S. House of Representatives (1831-33). Adair is at the eastern edge of Kentucky's Mississippi Plateau or Pennyroyal region and the western flank of the Appalachians . Most of it is heavily dissected with some large flat ridgetops in its central and . 2 sout h eastern sections. -

1988 Commencement Program

Academic Costumes The wearing of academic costumes is a custom that goes back to the Middle Ages. Since the early European and English universities were founded by the church, the students and teachers were required to wear distinctive gowns at all times. Although Morehead State University the custom was brought to this country in Colonial days, the requirement for students was soon dropped. The custom for professors was confined to special occasions such as graduating exercises and inaugurations of new presidents. With the increase in the number of educational institutions and the development of new subject-matter fields, some confusion arose in time about the type of gown and the specific color to denote various degrees. To introduce desirable uniformity and set up a clearing Class of 1988 house for new developments, a commission representing leading American colleges produced The lncercollegiace Code in 1895. In 1932, a national committee of the American Council on Education revised this code into The Academic Costume Code. It was revised in 1959. Although not obligatory, most of the educational institutions Spring Commencement in the country follow it in awarding their degrees, earned and honorary. The most significant part of the academic dress is the hood. The color of its velvet border indicates the academic field, and it is lined with the color or colors of the institution granting the degree. The hoods of those receiving a Master of Arts or an honorary degree of Doctor of Letters have those same color indications, but each successively higher degree carries with it a longer hood. The doctoral hood Saturday, May 14, 1988 also has side panels on the back. -

UA45/6 Commencement Program WKU Registrar

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® WKU Archives Records WKU Archives 5-6-1984 UA45/6 Commencement Program WKU Registrar Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/dlsc_ua_records Recommended Citation WKU Registrar, "UA45/6 Commencement Program" (1984). WKU Archives Records. Paper 1089. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/dlsc_ua_records/1089 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in WKU Archives Records by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'W;jiftimN-';I(;;;--V' , ~~~ 127th COMMENCEMENT /, _ , ~' ' .. A .~ .J I Western Kentucky University __. ............::: - ......£ ·i( Bowling Green, Kentucky ( ~" ...... -..... .,,~ . "".f,. Sunday, May 6, 1984 3:00p.m. E. A. Diddle Arena BOARD OF REGENTS Mr. Joe Bill Campbell, Chairman Bowling Green, Kentucky Mr. Joseph Iracane, Vice Chairman Owensboro, Kentucky Mr. Ronald W. Clark Franklin, Kentucky Mr. Joseph A. Cook II Bowling Green, Kentucky Mrs. Patsy Judd Burkesville, Kentucky Mrs. Mary Ellen Miller Bowling Green, Kentucky Mr. J. Anthony Page Paducah, Kentucky Mr. Ronald G. Sheffer Henderson, Kentucky Mr. Jack D. Smith Prospect, Kentucky Mrs. Hughlyne P. Wilson Prospect, Kentucky PROGRAM President Donald W. Zacharias, Presiding I Concert Selections .. .. ... .. .. .. ... ..... .. University Concert Band Dr. Kent Campbell, Conductor *Processional ... .. ....... ........ .. .. ....... University Concert Band "The Star-Spangled Banner" . ..................................... -

Moolah Shriners Volunteered Down at the Stanley Cup Championship Parade on Saturday, June 15Th! Photos Provided by Noble Greg Heins

Moolah® Shriners July & August • Volume 79, Issue 6 • St. Louis, MO Home of Shriners of Eastern & Central Missouri • Dedicated to Helping Shriners Hospitals for Children Jim Cain Jerry Gantt Imperial Potentate 2018-2019 Past Imperial Potentate 2015-2016 Chairman of the Board of Trustees Shriners Hospital for Children Moolah Appointed Positions Douglas Maxwell, P.P. 96 Past Imperial Potentate Potentate’s Aides David Dieckhaus, PP................................................Almoner Rich Viner, Chief Aide David Dieckhaus, PP.....................Ambassador Co. Chairman Past Imperial Chairman of Board of Trustees Wallace Bowman Patrick McEvoy Dennis Kelley, PP.......................Ambassador Co. Chairman 2009-2015 Matt Niedringhaus William Bradford Wayne Price.............................................Building Chairman Shriners Hospital for Children Michael Davis Tim Radley Ron Reynolds......................................................... Chaplain Kyle Eckhardt Richard Rammelsburg Mark Rethemeyer...........................Clinic Referral Chairman St. Louis 314-432-3600 Gary Fanger Brandon Rarey Steven Pieper, PP...............Donor Relations Co-Chairman Executive Board of Governors Gale Going Mike Reese Kenneth Myles, PP................Donor Relations Co-Chairman Gale Bennington, PP.........................................Chairman Harold Hargiss Dave Schmucker Ted Dearing.................................................General Counsel Dale Heise John Spraul David B. Schneidewind..........................Vice Chairman David Jacobi, -

William Blewett, the First Family Genealogy

William Blewett, The First Family Genealogy Compiled by Michael K. Blewett 5 Apr 2007 Created by www.AncestralAuthor.com WBlewett FamGen 1. William1 Blewett, Sr The First, born 20 Dec 1706, in Of, Cornwall County, England, died before 15 Jun 1790, in Anson County, NC, buried in Blewett Falls, NC. He married (1) Sarah Garton 30 Jul 1751, in Old Swedes Church, Wilmington, New Castle County, DE. She was the daughter of John Garton and Rebekah Gibbons. Sarah Garton was born about 1730, died about 1761, in Anson County, NC, buried in Blewett Falls, NC. He married (2) Miss White before 1761. Miss White died about 1761, in Blewett Falls, NC. He married (3) Elizabeth Morris about 1761, in Blewett Falls, Anson County, NC. Elizabeth Morris died about 1812, in Richmond County, NC. William Blewett, Esq. was transported from England to the colonies whenabout ten years old f or the trivial offense of cutting a riding switch ofa nobleman's land. He was brough up in P hiladelphia City in the tailortrade. From there removed to North Carolina on the Pee Dee Riv er, whichis on the line between Anson and Richmond Counties, when a young man. Onland Grante d to him by King George the Second and King George the Thirdof England. William Blewett wa s a Justice of the Peace for Anson County,NC in 1776. From: N. C. State Department of Archives and History Anson County Wills Book A, p. 34 (microfilms) No. 18 In the name of God Amen. I, William Blewett, of the county of Anson, State of North Carolina, being well in body and of sound mind and memory, calling to mind my own mortality, do think proper to make and constitutethis my last will and testament in manner and form floowing - Imprimis. -

The Absentee Shawnee News

COLOR The Absentee Shawnee News AUGUST 2014 VOL. 27 NO. 30 Inside This Issue... Anniversary Pow Wow PAGE 2-3................EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE REPORTS PAGE 4.................FINANCIAL CONSULTANT’S REPORT July 4-6, 2014 PAGE 5.................TAX COMMISSION & RESOLUTIONS Thunderbird PAGE 6.....................................TITLE VI MENU Casino PAGE 8.......................................CAMP NIKOTI See pictures of the winners in the PAGE 7...................ASHLEY, CADEN, ALYSSA, STEVI special insert inside PAGE 9-10...................................MSPI CAMP PAGE 11.........................CULTURAL PRESERVATION PAGE 13......................................EM ACTIVITY PAGE 16-17..........................AUGUST BIRTHDAYS PAGE 18..................SPOTLIGHT EMPLOYEE/ELECTION COMMISSION PAGE 22..................SCHOOL CLOTHING APPLICATION PAGE 23.................................BUILDING BLOCKS PAGE 24..............................................OEH PAGE 25...............................HORSE SHOE BEND PAGE 27..........................HEALTH SYSTEM UPDATE PAGE 30-31................................FOSTER CARE EXECUTIVE COMMITTee Edwina Butler-Wolfe Issac Gibson Vera M. Dawsey Leah Bates Kenneth Blanchard Governor Lt. Governor Secretary Treasurer Representative this year, to litigate with. Now where are we at today: On July 7, 2014 Keith Hall, City Commissioner for Ward 4 got the City Commissioners to discuss, consider, and possibly take action on an ordinance Governor’s Report (this is the City’s form of local law and is similar to when we pass a Tribal resolution) that allows Shawnee to place a Hello my Absentee Shawnee people! Charter amendment on the ballot for a referendum vote. This ballot, if passed, will allow the City to detach our land and the The recent rain is a nice change from the intense heat CPN’s land from the City of Shawnee. Why is this meaningful and humidity we have had. It is a relief to me that we are not to us here and as Tribal members? This could: suffering the extreme weather we have had in previous years. -

John Glenn Archives

John Glenn Archives Non-Senate Papers Sub-Group 1899 – 2017 Descriptive Finding Aid and Box and Folder Inventory Jeffrey W. Thomas 2017 Ohio Congressional Archives The Ohio State University Libraries 2700 Kenny Road Columbus, OH 43210 (614) 688-8429 Table of Contents Page Introduction….………………………………………. 3 Scope and Content Note Series 1: Family Records Series Sub-series 1: Family Records ………………. 4 Sub-series 2: Annie Glenn ………………….. 5 Series 2: Military Records ………………………….. 6 Series 3: NASA Records Sub-series 1: Mercury 7 Personal Files……………………….... 7 Working Files……………………….... 11 Sub-series 2: STS-95 ………………………... 13 Series 4: Corporate Records ……………………….. 15 Series 5: Post-Senate Records ……………………… 16 Series 6: Personal Correspondence…………………. 17 Box and Folder Inventory Series 1: Family Records Series Sub-series 1: Family Records ………………. 19 Sub-series 2: Annie Glenn ………………….. 26 Series 2: Military Records ………………………….. 39 Series 3: NASA Records Sub-series 1: Mercury 7 Personal Files ……………………….... 55 Working Files ……………………….... 100 Sub-series 2: STS-95 .………………………... 136 Series 4: Corporate Records .………………………… 164 Series 5: Post-Senate Records ..……………………… 184 Series 6: Personal Correspondence ………………….. 244 Introduction The Non-Senate Papers Sub-Group contains 147 cubic feet of records documenting the life of John H. Glenn, Jr. prior to and after his 1975 to 1999 career in the United States Senate. The sub-group contains records dating from 1942 to 1964 documenting the twenty-three years Glenn served as a combat and test pilot in the United States Marine Corps. Other records within the sub-group pertain to his assignment to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration from 1959 to 1964 as one of the original seven Project Mercury astronauts.