Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Itcontents 9..22

INTERNATIONAL TABLES FOR CRYSTALLOGRAPHY Volume F CRYSTALLOGRAPHY OF BIOLOGICAL MACROMOLECULES Edited by MICHAEL G. ROSSMANN AND EDDY ARNOLD Advisors and Advisory Board Advisors: J. Drenth, A. Liljas. Advisory Board: U. W. Arndt, E. N. Baker, S. C. Harrison, W. G. J. Hol, K. C. Holmes, L. N. Johnson, H. M. Berman, T. L. Blundell, M. Bolognesi, A. T. Brunger, C. E. Bugg, K. K. Kannan, S.-H. Kim, A. Klug, D. Moras, R. J. Read, R. Chandrasekaran, P. M. Colman, D. R. Davies, J. Deisenhofer, T. J. Richmond, G. E. Schulz, P. B. Sigler,² D. I. Stuart, T. Tsukihara, R. E. Dickerson, G. G. Dodson, H. Eklund, R. GiegeÂ,J.P.Glusker, M. Vijayan, A. Yonath. Contributing authors E. E. Abola: The Department of Molecular Biology, The Scripps Research W. Chiu: Verna and Marrs McLean Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Institute, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA. [24.1] Biology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas 77030, USA. [19.2] P. D. Adams: The Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Department of Molecular J. C. Cole: Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge Biophysics and Biochemistry, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511, USA. CB2 1EZ, England. [22.4] [18.2, 25.2.3] M. L. Connolly: 1259 El Camino Real #184, Menlo Park, CA 94025, USA. F. H. Allen: Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge [22.1.2] CB2 1EZ, England. [22.4, 24.3] K. D. Cowtan: Department of Chemistry, University of York, York YO1 5DD, U. W. Arndt: Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Medical Research Council, Hills England. -

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize Winners Part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize winners part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin By Cambridge News | Posted: January 18, 2016 By Adam Care The News has been rounding up all of Cambridge's 92 Nobel Laureates, celebrating over 100 years of scientific and social innovation. ADVERTISING In this installment we move from 1951 to 1974, a period which saw a host of dramatic breakthroughs, in biology, atomic science, the discovery of pulsars and theories of global trade. It's also a period which saw The Eagle pub come to national prominence and the appearance of the first female name in Cambridge University's long Nobel history. The Gender Pay Gap Sale! Shop Online to get 13.9% off From 8 - 11 March, get 13.9% off 1,000s of items, it highlights the pay gap between men & women in the UK. Shop the Gender Pay Gap Sale – now. Promoted by Oxfam 1. 1951 Ernest Walton, Trinity College: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei 2. 1951 John Cockcroft, St John's / Churchill Colleges: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei Walton and Cockcroft shared the 1951 physics prize after they famously 'split the atom' in Cambridge 1932, ushering in the nuclear age with their particle accelerator, the Cockcroft-Walton generator. In later years Walton returned to his native Ireland, as a fellow of Trinity College Dublin, while in 1951 Cockcroft became the first master of Churchill College, where he died 16 years later. 3. 1952 Archer Martin, Peterhouse: Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for developing partition chromatography 4. -

Crystal Vision Dorothy Hodgkin & the Nobel Prize “Few Were Her Equal in Generosity of Spirit, Breadth of Mind, Cultivated Humaneness, Or Gift for Giving

Crystal Vision Dorothy Hodgkin & the Nobel Prize “Few were her equal in generosity of spirit, breadth of mind, cultivated humaneness, or gift for giving. She should be remembered not only for a lifetime’s succession of brilliantly achieved structures. While those who knew her, experienced her quiet and modest and extremely powerful influence, learned from her more than the positioning of atoms in the three-dimensional molecule, she will be remembered not only with respect, and reverence, and gratitude, but more than anything else, with love. Let that be her lasting memorial.” Anne Sayre, in the Autumn 1995 Newsletter of the American Crystallographic Association Cover image © Emilio Segre Visual Archives/American Institute of Physics/Science Photo Library Letter from the Principal Dr Alice Prochaska, Somerville College Many remarkable woman scientists have passed through Somerville, but few rival Dorothy Hodgkin, whose path-breaking work in crystallography showed a mind not only attuned to high science but one also able to envision a crystal structure from the pattern made by its X-ray diffraction. Her ability to ‘see’ molecules such as cholesterol, penicillin, vitamin B and insulin transformed her field. 2014 sees the fiftieth anniversary of Professor Hodgkin’s Nobel prize. It is also the International Year of Crystallography, marking the 100th anniversary of Max von Laue’s Nobel Prize for Physics, awarded for his discovery that X-rays could be diffracted by crystals. That discovery underpinned Dorothy Hodgkin’s work. We are proud that Somerville supported her at a time when there was widespread opposition to married women pursuing academic careers. -

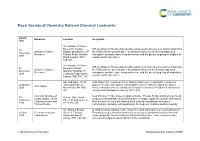

RSC Branding

Royal Society of Chemistry National Chemical Landmarks Award Honouree Location Inscription Date The Institute of Cancer Research, Chester ICR scientists on this site and elsewhere pioneered numerous new cancer drugs from 10 Institute of Cancer Beatty Laboratories, 237 the 1950s until the present day – including the discovery of chemotherapy drug December Research Fulham Road, Chelsea carboplatin, prostate cancer drug abiraterone and the genetic targeting of olaparib for 2018 Road, London, SW3 ovarian and breast cancer. 6JB, UK The Institute of Cancer ICR scientists on this site and elsewhere pioneered numerous new cancer drugs from 10 Research, Royal Institute of Cancer the 1950s until the present day – including the discovery of chemotherapy drug December Marsden Hospital, 15 Research carboplatin, prostate cancer drug abiraterone and the genetic targeting of olaparib for 2018 Cotswold Road, Sutton, ovarian and breast cancer. London, SM2 5NG, UK Ape and Apple, 28-30 John Dalton Street was opened in 1846 by Manchester Corporation in honour of 26 October John Dalton Street, famous chemist, John Dalton, who in Manchester in 1803 developed the Atomic John Dalton 2016 Manchester, M2 6HQ, Theory which became the foundation of modern chemistry. President of Manchester UK Literary and Philosophical Society 1816-1844. Chemical structure of Near this site in 1903, James Colquhoun Irvine, Thomas Purdie and their team found 30 College Gate, North simple sugars, James a way to understand the chemical structure of simple sugars like glucose and lactose. September Street, St Andrews, Fife, Colquhoun Irvine and Over the next 18 years this allowed them to lay the foundations of modern 2016 KY16 9AJ, UK Thomas Purdie carbohydrate chemistry, with implications for medicine, nutrition and biochemistry. -

Max Ferdinand Perutz 1914–2002

OBITUARY Max Ferdinand Perutz 1914–2002 Max Ferdinand Perutz, who died on in the MRC Laboratory of Molecular 6 February, will be remembered as Biology, which has grown to house one of the 20th century’s scientific over 400 people. He published over giants. Often referred to as the ‘fa- 100 papers and articles during his re- ther of molecular biology’, his work tirement. Once asked why he didn’t re- remains one of the foundations on tire at 65 he replied that he was tied up which science is being built today. in some very interesting research at Born in Vienna in 1914, Max was the time. Until the Friday before educated in the Theresianum, a Christmas, he was active in the lab al- grammar school originating from most every day, submitting his last an earlier Officers’ academy. His paper just a few days before then. parents suggested that he study law Max’s scientific interests ranged far to prepare for entering the family beyond medical research. As a sideline, business, but he chose to study he also worked on glaciers in his chemistry at the University of youth. He studied the transformation Vienna. of snowflakes that fall on glaciers into In 1936, with financial support the huge single ice crystals that make from his father, he began a PhD at the Cavendish up its bulk, and the relationship between the mechanical Laboratory in Cambridge. Using X-ray crystallography he properties of ice measured in the laboratory and the mecha- aimed to determine the structure of hemoglobin. But the nism of glacier flow. -

Robert Burns Woodward

The Life and Achievements of Robert Burns Woodward Long Literature Seminar July 13, 2009 Erika A. Crane “The structure known, but not yet accessible by synthesis, is to the chemist what the unclimbed mountain, the uncharted sea, the untilled field, the unreached planet, are to other men. The achievement of the objective in itself cannot but thrill all chemists, who even before they know the details of the journey can apprehend from their own experience the joys and elations, the disappointments and false hopes, the obstacles overcome, the frustrations subdued, which they experienced who traversed a road to the goal. The unique challenge which chemical synthesis provides for the creative imagination and the skilled hand ensures that it will endure as long as men write books, paint pictures, and fashion things which are beautiful, or practical, or both.” “Art and Science in the Synthesis of Organic Compounds: Retrospect and Prospect,” in Pointers and Pathways in Research (Bombay:CIBA of India, 1963). Robert Burns Woodward • Graduated from MIT with his Ph.D. in chemistry at the age of 20 Woodward taught by example and captivated • A tenured professor at Harvard by the age of 29 the young... “Woodward largely taught principles and values. He showed us by • Published 196 papers before his death at age example and precept that if anything is worth 62 doing, it should be done intelligently, intensely • Received 24 honorary degrees and passionately.” • Received 26 medals & awards including the -Daniel Kemp National Medal of Science in 1964, the Nobel Prize in 1965, and he was one of the first recipients of the Arthur C. -

Max Perutz (1914–2002)

PERSONAL NEWS NEWS Max Perutz (1914–2002) Max Perutz died on 6 February 2002. He Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1962 with structure is more relevant now than ever won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in his colleague and his first student John as we turn attention to the smallest 1962 after determining the molecular Kendrew for their work on the structure building blocks of life to make sense of structure of haemoglobin, the red protein of haemoglobin (Perutz) and myoglobin the human genome and mechanisms of in blood that carries oxygen from the (Kendrew). He was one of the greatest disease.’ lungs to the body tissues. Perutz attemp- ambassadors of science, scientific method Perutz described his work thus: ted to understand the riddle of life in the and philosophy. Apart from being a great ‘Between September 1936 and May 1937 structure of proteins and peptides. He scientist, he was a very kindly and Zwicky took 300 or more photographs in founded one of Britain’s most successful tolerant person who loved young people which he scanned between 5000 and research institutes, the Medical Research and was passionately committed towards 10,000 nebular images for new stars. Council Laboratory of Molecular Bio- societal problems, social justice and This led him to the discovery of one logy (LMB) in Cambridge. intellectual honesty. His passion was to supernova, revealing the final dramatic Max Perutz was born in Vienna in communicate science to the public and moment in the death of a star. Zwicky 1914. He came from a family of textile he continuously lectured to scientists could say, like Ferdinand in The Tempest manufacturers and went to the Theresium both young and old, in schools, colleges, when he had to hew wood: School, named after Empress Maria universities and research institutes. -

Facts and Figures 2013

Facts and Figures 201 3 Contents The University 2 World ranking 4 Academic pedigree 6 Areas of impact 8 Research power 10 Spin-outs 12 Income 14 Students 16 Graduate careers 18 Alumni 20 Faculties and Schools 22 Staff 24 Estates investment 26 Visitor attractions 28 Widening participation 30 At a glance 32 1 The University of Manchester Our Strategic Vision 2020 states our mission: “By 2020, The University of Manchester will be one of the top 25 research universities in the world, where all students enjoy a rewarding educational and wider experience; known worldwide as a place where the highest academic values and educational innovation are cherished; where research prospers and makes a real difference; and where the fruits of scholarship resonate throughout society.” Our core goals 1 World-class research 2 Outstanding learning and student experience 3 Social responsibility 2 3 World ranking The quality of our teaching and the impact of our research are the cornerstones of our success. 5 The Shanghai Jiao Tong University UK Academic Ranking of World ranking Universities assesses the best teaching and research universities, and in 2012 we were ranked 40th in the world. 7 World European UK European Year Ranking Ranking Ranking ranking 2012 40 7 5 2010 44 9 5 2005 53 12 6 2004* 78* 24* 9* 40 Source: 2012 Shanghai Jiao Tong University World Academic Ranking of World Universities ranking *2004 ranking refers to the Victoria University of Manchester prior to the merger with UMIST. 4 5 Academic pedigree Nobel laureates 1900 JJ Thomson , Physics (1906) We attract the highest calibre researchers and Ernest Rutherford , Chemistry (1908) teachers, boasting 25 Nobel Prize winners among 1910 William Lawrence Bragg , Physics (1915) current and former staff and students. -

Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY

Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY Theo James presenting a bouquet to HM The Queen on the occasion of her bicentenary visit, 7 December 1999. by Frank A.J.L. James The Director, Susan Greenfield, looks on Front page: Façade of the Royal Institution added in 1837. Watercolour by T.H. Shepherd or more than two hundred years the Royal Institution of Great The Royal Institution was founded at a meeting on 7 March 1799 at FBritain has been at the centre of scientific research and the the Soho Square house of the President of the Royal Society, Joseph popularisation of science in this country. Within its walls some of the Banks (1743-1820). A list of fifty-eight names was read of gentlemen major scientific discoveries of the last two centuries have been made. who had agreed to contribute fifty guineas each to be a Proprietor of Chemists and physicists - such as Humphry Davy, Michael Faraday, a new John Tyndall, James Dewar, Lord Rayleigh, William Henry Bragg, INSTITUTION FOR DIFFUSING THE KNOWLEDGE, AND FACILITATING Henry Dale, Eric Rideal, William Lawrence Bragg and George Porter THE GENERAL INTRODUCTION, OF USEFUL MECHANICAL - carried out much of their major research here. The technological INVENTIONS AND IMPROVEMENTS; AND FOR TEACHING, BY COURSES applications of some of this research has transformed the way we OF PHILOSOPHICAL LECTURES AND EXPERIMENTS, THE APPLICATION live. Furthermore, most of these scientists were first rate OF SCIENCE TO THE COMMON PURPOSES OF LIFE. communicators who were able to inspire their audiences with an appreciation of science. -

CV Sir Arthur Harden

Curriculum Vitae Prof. Dr. Arthur Harden Name: Sir Arthur Harden Lebensdaten: 12. Oktober 1865 ‐ 17. Juni 1940 Arthur Harden war ein britischer Chemiker. Nach ihm sind die Harden‐Young‐Ester (Zuckerphospha‐ te) benannt. Für seine Forschungen über die Gärung von Zucker und dessen Gärungsenzyme wurde er im Jahr 1929 gemeinsam mit dem deutsch‐schwedischen Chemiker Hans von Euler‐Chelpin mit dem Nobelpreis für Chemie ausgezeichnet. Werdegang Arthur Harden studierte von 1882 bis 1885 Chemie am Owens College der University of Manchester. 1868 ging er mit einem Dalton Scholarship an die Universität Erlangen, um beim Chemiker Otto Fi‐ scher, einem Vetter von Emil Fischer (Nobelpreis für Chemie 1902), zu arbeiten. Dort wurde er 1888 promoviert. Im Anschluss arbeitete er als Dozent am Owens College. Ab 1897 war er am neu gegrün‐ deten British Jenner Institute of Preventive Medicine tätig. 1907 wurde er dort Leiter der Abteilung Biochemie. Außerdem erhielt er 1912 eine Professur für Biochemie an der University of London. Auch nach seiner Emeritierung im Jahr 1930 blieb Harden wissenschaftlich aktiv. So befasste er sich unter anderem mit dem Stoffwechsel von E.coli‐Bakterien sowie mit der Gärung. Gemeinsam mit dem deutsch‐schwedischen Wissenschaftler Hans von Euler‐Chelpin gelang es ihm, diesen Vorgang vollständig aufzuklären. Nobelpreis für Chemie 1929 Die Aufklärung der Gärung als eine der ältesten biologischen Technologien der Menschheit hatte bereits zuvor viele Wissenschaftler zu Forschungsarbeiten angeregt, unter ihnen Louis Pasteur und Justus Freiherr von Liebig. Arthur Harden wurde für seine Forschungen über die Gärung von Zucker und die daran beteiligten Gärungsenzyme im Jahr 1929 gemeinsam mit Hans von Euler‐Chelpin mit dem Nobelpreis für Chemie ausgezeichnet. -

Honorary Graduates – 1966 - 2004

THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK HONORARY GRADUATES – 1966 - 2004 1966 MR PATRICK BLACKETT, physicist THE RT HON LORD GARDINER, Lord Chancellor SIR PETER HALL, director of plays and operas PRESIDENT KAUNDA, Head of State SIR HENRY MOORE, sculptor SIR ROBERT READ, poet and critic THE RT HON LORD ROBBINS, economist SIR MICHAEL TIPPETT, musician and composer THE RT HON BARONESS WOOTTON OF ABINGER 1967 SIR JOHN DUNNINGTON-JEFFERSON, for services to the University DR ARTHUR GLADWIN. For services to the University PROFESSOR F R LEAVIS, literary critic PROFESSOR WASSILY LEONTIEFF, economist PROFESSOR NIKLAUS PEVSNER, art & architecture critic and historian 1968 AMADEUS QUARTET NORBET BRAININ MARTIN LOVELL SIGMUND NISSELL PETER SCHIDLOF PROFESSOR F W BROOKS, historian LORD CLARK, art historian MRS B PAGE, librarian LORD SWANN, Biologist (and Director-General of the BBC) DAME EILEEN YOUNGHUSBAND, social administrator 1969 PROFESSOR L C KNIGHTS, literacy critic SIR PETER PEARS, singer SIR GEORGE PICKERING, scholar in medicine SIR GEORGE RUSSELL, industrial designer PROFESSOR FRANCIS WORMALD, historian 1969 Chancellor’s installation ceremony THE EARL OF CRAWFORD AND BALCARRES, patron of the arts MR JULIAN CAIN, scholar and librarian PROFESSOR DAVID KNOWLES, historian MR WALTER LIPPMAN, writer & journalist 1970 PROFESSOR ROGER BROWN, social psychologist THE RT HON THE VISCOUNT ESHER, PROFESSOR DOROTHY HODGKIN, chemist PROFESSOR A J P TAYLOR, historian 1971 DAME KITTY ANDERSON, headmistress DR AARON COPLAND, composer DR J FOSTER, secretary-General of the Association -

All Living Organisms Are Organised Into Large Groups Called Kingdoms. Fungi Were Orig

What are fungi and how important are they? All living organisms are organised into large groups called Kingdoms. Fungi were originally placed in the Plant Kingdom then, scientists learned that fungi were more closely related to animals than to plants. Then scientists decided that fungi were not sufficiently similar to animals to be placed in the animal kingdom and so today fungi have their own Kingdom – the Fungal Kingdom. There are thought to be around up to 3.8 million species of fungi, of which only 120,000 have been named. The fungal kingdom is largely hidden from our view and we usually only see the “fruit” of a fungus. The living body of a fungus is called a mycelium and is made up of a branching network of filaments known as hyphae. Fungal mycelia are usually hidden in a food source like wood and we only know they are there when they develop mushrooms or other fruiting bodies. Some fungi only produce microscopic fruiting bodies and we never notice them. Fungi feed by absorbing nutrients from the organic material that they live in. They digest their food before they absorb it by secreting acids and enzymes. Different fungi have evolved to live on various types of organic matter, some live on plants (Magneportha grisea – the rice blast fungus), some on animals (Trichophyton rubrum - the athlete’s foot fungus) and some even live on insects (Cordyceps australis). Helpful fungi Most of us use fungi every day without even knowing it. We eat mushrooms and Quorn, but we also prepare many other foods using fungi.